At a hurriedly convened council of war, the Greeks weighed the unappetising options that now lay before them. To abandon their positions by daylight would clearly be tantamount to suicide: the Persian cavalry would cut them to ribbons. Yet to postpone a withdrawal would be just as disastrous: thirsty already, the Greeks were also starting to go hungry, as the barbarians, raiding the Cithaeron passes, continued their policy of plundering the allied food convoys. The obvious solution, despite all the monstrous risks of confusion that it would entail, was a retreat by night. Pausanias therefore instructed the various allied contingents that, come darkness, they were to withdraw two miles to a new line directly east of Plataea. Here, everyone agreed, their position would be infinitely stronger. The foothills would offer them excellent protection against cavalry. They would be well placed to secure the passes over Cithaeron. They would have plentiful supplies of water. Indeed, there was only one real drawback: the Greeks had to reach their new line first.

And that was no simple matter. In the centre, where the soldiers of a whole host of different cities, stumbling through the night, were obliged to pick their way over thoroughly unfamiliar terrain, the retreat soon veered badly off course. Thirsty, hungry and nervous as they were, it was hardly surprising, perhaps, that they should have missed the appointed rendezvous and ended up instead over a mile to the west, almost directly before the ruins of Plataea, where ‘they scattered and pitched their tents at random’. Meanwhile, on the wings, the confusion was worse still. As the sky began to lighten, neither the Athenians nor, at the opposite end of the battle-line, the Lacedaemonians and Tegeans had even begun their retreat. The three contingents, mandated to serve as rearguards, seem to have found themselves, due to the general chaos and the delay of their allies’ withdrawal, stranded at their outposts throughout the night. And now birds were starting to sing along the river, and the enemy camped out on the opposite bank to stir.

The Athenians panicked. A horseman was sent galloping over the fields to the Spartan camp, to demand what was going on. Arriving there, he found Pausanias and his staff officers engaged in a furious discussion. What precisely was being debated would later be a matter of much controversy. Some would claim that Pausanias was facing direct insubordination: a Spartan officer by the name of Amompharetus was said to have insisted that retreat was no better than cowardice, and refused to obey his general’s orders. A second tradition, however, commemorated the same officer as one of the three Spartans who fought with most distinction at Plataea: hardly an award that suggests a record of mutiny. Far from disobeying Pausanias’ orders, then, it appears likeliest that Amompharetus had been demanding for his men the honour of a uniquely perilous mission: for with the sun about to rise, and the withdrawal of the Lacedaemonians and Tegeans still to begin, a division was desperately needed to hold the ridge until as late as possible. So it was that Amompharetus and his men, even as Pausanias gave the order for their Spartan comrades and the Athenians to start their retreat, remained where they were, shields and helmets at the ready, grimly resolved to hold their position for as long as they could. And already, fanning out from the far bank, horsemen could be seen splashing across the river and cantering towards their camp.

Carefully, the Persian scouts reconnoitred all the deserted allied positions. News of the enemy withdrawal, brought back to Mardonius where he waited with the infantry, was soon confirmed for him, as the sun rose, by the dramatic evidence of his own eyes. The fragmentation of the Greek battle-line, the task that he had set himself from the start of the campaign, had been spectacularly achieved — and without his once having had to fight the enemy on their own terms. Most gratifyingly of all, the Spartans, the supposedly invincible, iron-souled Spartans, were still in open retreat, isolated from their allies, and as vulnerable as they would ever be. Risky, of course, to engage a phalanx in open battle – especially a Spartan phalanx – but Mardonius knew that he would never have a better chance to tear out the heart of the allied army. Already the window of opportunity was closing fast. Fail to seize the moment, and the Spartans would complete their rendezvous. So that Mardonius, climbing into the saddle of a towering white Nisaean stallion, gave the elite squads of infantry massed around him the fateful order to advance. They began to wade through the shallows of the Asopus. As they did so, all along the Persian battle-line, banners were raised amid great cheering, and every unit in Mardonius’ army, moving in disordered eagerness whether it was with their general’s permission or not, surged forwards down the river bank.

And now, as the haze of dawn glimmered and was burned up by the rising sun, there shuddered through the Lacedaemonian ranks that ‘dense, bristling glitter of shields and spears and helmets’ which had always served to alert warriors that a time of slaughter was approaching, and that the gods themselves were near. From beside the temple grove where he had ordered his men to halt and prepare for battle, Pausanias could see Amompharetus and his division retreating uphill with measured discipline, even as the Persian horsemen, massing behind them, came wheeling in pursuit. Pausanias had heard the savage cries of the barbarians from the river, and then watched them cross it in a monstrous, banner-swept tide. He knew that soon not only cavalry but the whole weight of Mardonius’ elite infantry battalions would be assaulting his shield-wall. Frantically, while he still had the chance, he sent a messenger to the Athenians, begging them to join him —but the message arrived too late. Even as Aristeides turned and began leading his men crab-wise towards the Lacedaemonian positions, he felt the earth shaking, and saw over his shoulder the battle-line of the Thebans drawing down upon them. The clash of the two phalanxes rang across the battlefield; and confirmed Pausanias, a mile away to the east, in all his apprehensions of the worst.

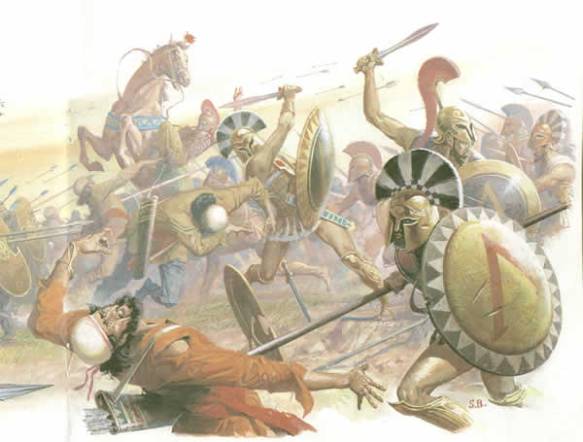

True, there was some relief to be had in the breathless arrival of Amompharetus and his men; but there could be no hope now of any other reinforcements coming to swell the phalanx’s numbers. Alone, then, the Spartans and the Tegeans would have to face Mardonius: 11,500 men against the elite of a superpower. Already, fired by the wheeling, darting Saka, arrows were rattling down upon their shield-wall. Then, from behind the horsemen, barely visible through the hail of missiles, and all the more terrifying for it, the measured, thunderous approach of the barbarians’ crack infantry divisions could be felt. Mardonius’ cavalry withdrew; his infantry, maintaining their distance from the bristling phalanx, planted a wall of wicker shields; the rain of arrows began to thicken.

Still the cornered Greeks maintained their discipline. Holding up their shields, they listened from within their helmets to the eerily dimmed hiss and thud of ceaseless missiles all about them. Men began to stumble and fall, the arrows protruding from groins or shoulders bloody to the fletching; and now, every Lacedaemonian and Tegean began to think, was the time for the phalanx to make its charge across no man’s land, to crash into the wall of flimsy wicker, to stab and trample its tormentors underfoot. But still Pausanias held back his warriors. Only once the approval of Artemis for the great enterprise of combat ahead of them had been clearly discerned in a blood-sacrifice could he give the order to advance; and the goddess, no matter how many goats were slaughtered in her honour, refused to grant the Greeks her blessing. At last, in despair, Pausanias raised a prayer directly to the heavens, ‘and a moment later the victims, when they were sacrificed, promised success at last’. Just as well: for even as Pausanias was ordering the phalanx to advance, the Tegeans had already begun running towards the Persian lines — and a single Spartan with them. Of the Tegeans, who lacked the authentic Lycurgan discipline, such intemperance might, perhaps, have been expected; but not of Aristodemus, that graduate of the ‘agoge. And yet the ‘trembler’ — even though he could hardly be honoured for breaking from his place in the Spartan shield-wall, for throwing himself single-handed upon the barbarians, for killing and being killed in a frenzy so berserk as to be barely Greek — had nevertheless, his mess-mates agreed later, redeemed his name. Indeed, his courage would long be remembered by the men of other cities as something truly exceptional. To that extent, at least, it could be reckoned that Aristodemus had died a Spartan.

All the same, true glory in Sparta went to those who fought not in the cause of their own selfish honour but as links in a single machine; and great glory, that terrible morning, was won by every member of the phalanx. Only ‘Dorian spears, clotting the earth of Plataea with the butchery of a blood-sacrifice’, could possibly have secured the victory; for only the men who grasped them had been steeled from birth to fight, to kill and never to yield. Descending the arrow-darkened slope of no man’s land, smashing into the enemy’s front line, the Spartans faced a test for which their whole lives had been preparation. Other men, perhaps, shoving against an enemy as teeming, as celebrated and as courageous as the Persians, would have found their spirits failing, their shield arms wearying, their bodies aching; but not the Spartans. Long though the battle appeared to hang in the balance, they did not cease to grind implacably forwards. No matter that the Persians, in their growing desperation, sought to impede their enemy’s advance by taking hold of the Spartans’ spears and splintering them; swords were not so easily snapped, nor the weight of bronze-clad bodies stopped. Still Mardonius, ‘as brave as any Persian on the field’, sought to rally his troops; but by now the Spartans were closing in on the elite that formed his bodyguard, and Mardonius himself, resplendent on his white charger, made for an easy target. A Spartan, picking up a stone, flung it at him, and the missile smashed into the side of his skull; and down from his saddle tumbled the cousin of the Great King, the man who had thought to be Satrap of Greece.

And the Persians, watching him fall, knew the battle lost. Mardonius’ guardsmen, holding their ground heroically, were wiped out where they stood, but the remainder of the divisions, demoralised by the death of their charismatic general, began to run, and soon the rout was general over the battlefield. Forty thousand men, led by a quick-thinking officer, managed to escape northwards onto the road to Thessaly, but most, stampeding in their panic, made for the fort, and the Lacedaemonians and Tegeans pursued them there. Soon enough, Pausanias was joined before the gates of the fort by the. Athenians, whose bitter grudge-match against the Thebans had ended with the medisers breaking and fleeing for their city. Now, together at last, the victorious allies forced the palisade. The massacre that followed was almost total: of the shattered remnants of Mardonius’ army, barely three thousand were spared. And so ended the enterprise of the Great King against the West.

Gawping at the wealth and luxury displayed in Mardonius’ camp, the Greeks again found themselves wondering why he had felt such a burning desire to conquer their land, when, self-evidently, he had more than enough already. One trophy, in particular, served to bring home to them the full, improbable scale of their victory: the King of King’s own tent. Xerxes, it was said, leaving Greece the previous autumn, had granted to Mardonius the use of his campaign headquarters; and so Pausanias, parting its embroidered hangings, walking over its perfumed carpets, took possession of what the previous year had been the nerve-centre of the world. Gazing in astonishment at the furnishings, the Regent pondered what it would be like to sit where the death of his uncle had been plotted; and so he ordered Mardonius’ cooks to prepare him a royal dinner. When it was ready, he had a second dinner of Spartan black broth laid out beside it, and invited his fellow commanders to come in and admire the contrast. ‘Men of Greece,’ Pausanias laughed, ‘I have invited you so that you could appreciate for yourselves the irrational character of the Mede, who has a lifestyle such as you see here laid out before you, and yet who came here to our country to rob us of our wretched poverty.’ A joke; and yet, of course, not wholly so. Freedom was no laughing matter. Few of the sweat-stained Greek commanders, gazing at the obscene luxury of the Great King’s table and then comparing it with the bowls of simple soup, could have doubted to what the barbarians owed their defeat, and their own cities their liberty.

Meanwhile, beyond the tasselled doorways of the tent, the helots were hard at work, grubbing through the camp. Ordered by Pausanias to make a great pile of the loot, they lugged furniture out of tents, shoved golden plate into sacks, and pulled rings off the fingers of corpses. Naturally, they refrained from declaring all that they found; what they could, they salted away. With these scavengings, the helots hoped to secure their own liberty; but they were ignorant and backward, and so proved easy meat for conmen. A consortium of Aeginetans, smelling an easy profit, managed to persuade the helots that their gold was brass, and paid for it accordingly. The helots, comprehensively ripped off, appear not to have won their freedom; but the Aeginetans, it is said, made a killing.