Robert E. Lee

The first great battle came on July 21, 1861, a few months after the Confederate shelling of Fort Sumter. At the Battle of First Bull Run fought near the Union capital, a Southern army defeated its Union counterpart in a hard-fought struggle that lasted most of the day. The loss of life testified to the folly of hoping for a bloodless war: almost 2,000 killed and wounded on each side. Additionally, the spectators from Washington D. C. who turned out to watch the “contest” also highlighted the folly surrounding the war in its opening months; the war would not be a colorful display. Lincoln’s call to arms of a ninety-day militia would be another reminder. He soon concluded that a more permanent standing army would be necessary to win the struggle. Both sides now prepared for a longer war. Taking this step at last indicated that the state of disbelief that had in no small measure drove the South to arms had finally dissipated.

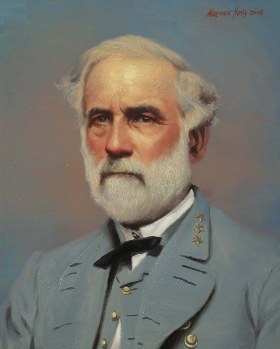

Repetition would eliminate any lingering hopes of a short, bloodless war. The Battle of Bull Run was fought again the following year, although the result was the same, a Southern victory. In this eastern theater of war, the opposing sides would face each other in a series of battles that revealed a grudge match taking shape that produced a slowly escalating conflict and mounting casualties. Early on, the South got the best of these battles and in no small part due to the fact that a number of brilliant leaders did surface to aid its cause. Foremost in this regard was Robert E. Lee. A trusted military advisor to Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, Davis named Lee commander of what would become the Army of Northern Virginia in 1862. His command came at a fortuitous time, for the North had again assumed the offensive and threatened Richmond, the Southern capital. Lee defeated General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac in a number of battles fought over seven days, eventually ending the threat to Richmond and sending the Union forces back to their defenses surrounding Washington D. C. The bloodshed had been acute, the Peninsula Campaign claiming 16,000 Union casualties, 20,000 Confederates. Lee’s peers deemed his operations a success. Lee was less convinced that his “offensive-defensive” strategy had succeeded. The peril to Richmond had ended, but the Union army had not been destroyed. This latter aim had been Lee’s objective, massing military force to avoid a passive defense and so win a decisive victory.

Lee now assumed overall command of the Confederate armies in the east. It was in this capacity that Lee made a crucial decision. The South must assume the offensive and attack the North, he believed, rather than await another Union attack. Continued fighting would only wear down his forces, the North turning to its inexhaustible manpower to eventually force the Confederacy to submit. A Southern offensive into Union territory turned the tables. It brought the Union army to a battlefield of Lee’s choosing, and with the destruction of that army, this defeat would bring the war home to the North. Northerners would then sue for peace. In assuming the offensive, Lee desired no permanent territorial objectives. The South was not expanding. Rather, the South was dictating a tempo that it hoped would produce a decisive battle to force the North to make peace. The South could then enjoy its status as a separate nation.

Lee’s strategy was remarkable for many reasons. For one thing, it admitted what had been denied by Southerners in the rush to war: the great material advantage the North enjoyed could defeat the South. Additionally, his offensive plans transgressed on the hopes of fighting a successful defensive war. It must have been troubling to Southern partisans that Lee would stick with the strategy of invading the North despite winning two great defensive battles, Fredericksburg in December 1862, and Chancellorsville in early May 1863. A certain desperation influenced his determination to invade the North. At least the South would not be burdened with having to conquer the North, as did the North when it attacked the South. This great strategic principle remained intact, and it did somewhat bolster Lee’s strategy. But Lee’s decision eliminated the last shred of optimism that had accompanied the South into the war, since his offensive plans forfeited the assumed advantages of staying on the defensive that had preceded the conflict. Lee gambled that he could force the North into a negotiated peace before the North simply wore down the South and won the war on the basis of attrition alone. He needed a great battle to offset the prospect of a long, agonizing war that would cost many lives.

Lee soon adopted his strategy to try and end the war by invading the North and forcing a settlement. On two occasions, he led his army into Northern territory only to meet defeat both times. In September 1862, after a bloody struggle he held the battlefield of Antietam and won the day. It was ugly carnage, some 22,000 soldiers dead and wounded on both sides about equally distributed between the opponents. But Lee had failed to gain his decisive victory. Worse, he lost the edge he sought because he had to withdraw from Maryland back into Virginia, turning his battlefield victory into a strategic defeat. He had failed to win a battle that forced a peace. He tried again. The following year, 1863, saw a larger bloodbath, a clear Lee defeat, and an end to Lee’s strategy. In three days in July, the opposing armies inflicted some 51,000 casualties on one another at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. This time around Lee’s army suffered more than did the Army of the Potomac, though the Northern army’s losses of over 23,000 were great as well. But Lee again was forced to retreat, and his bid to take the fighting to the North ended.

The North now moved closer to waging a total war, its efforts a conscious attempt to conquer the South. This strategy came from U. S. Grant, a general fighting for the Union who possessed as much ability as Lee. Grant’s talent, however, came in a specific form, a cold determination to see the war to an end no matter how great the cost in lives. This was less callous indifference on Grant’s part to loss of life than it was a careful reading of the era of war he now found himself fighting in. He believed the time of the decisive battle had passed, and a new strategy was imperative. This involved coordinating multiple theaters of action, and waging war with an abandon that could not have been anticipated even by those fearing the scourge of war prior to the start of the fighting. The contrast to Lee was complete. Lee never coordinated the Confederacy’s war effort on multiple fronts. His goal was seeking a decisive battle in the east that he believed offered a sort of remedy to the horrible nature of the conflict; the day-long battle could end the conflict and save lives by eliminating the need for further fighting. Even as the body counts rose with each battle, Lee clung to his belief in the decisive battle, at least up to Gettysburg. After this defeat, Lee only hoped to inflict enough losses on the North so that the war ended in stalemate. For this reason, Lee bore as much responsibility as did Grant for the horrendous causalities that characterized the last few years of the war.

Grant quickly turned Lee into a victim of total war. The Union general directed a series of offensives by the Army of the Potomac starting in 1864 that reduced Lee’s army to a beleaguered rabble clinging to a chain of fortifications defending the town of Petersburg. In the western theater of the war, a trusted Grant lieutenant, William Tecumseh Sherman, marched on Atlanta, Georgia, and then to the coast on a deliberate mission to inflict harm on the Southern interior, more specifically to terrorize civilians. By December 1864, Sherman had reached Savannah and it was clear that the war had taken a horrible turn. The war in the west produced a swath of destruction seldom seen in North America. The campaign in the east had cost thousands of lives. Once Lee gave way at Petersburg, Richmond fell to Union forces in the first few days of April 1865, and Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9. A few Southern generals tried to hold out, but Lee’s capitulation essentially ended the war.

Lee may have got much wrong, but other factors were also significant in explaining his defeat. Most importantly, the South’s bid for a preemptive war had failed completely. The Northern material edge in military resources had proved the deciding factor, no matter the indomitable Southern spirit or the brilliant Southern generalship. To uphold its culture the South had turned to preemptive warfare as a means of self-preservation. It ended this war a conquered state. By fighting, the South had achieved its preemptive purpose, that it would be destroyed one way or the other: either a Northern ascendancy would eclipse the Southern lifestyle sooner or later, or the South would fight a heroic war and lose, and thereby forfeit its culture as well. Never had preemption served such a forlorn hope.