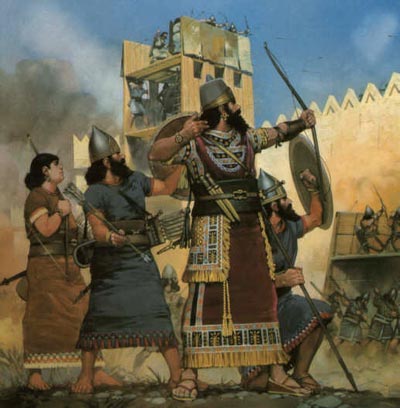

Assyrian Besiegers

Wars and warfare played an important role in the societies of the ancient Near East. The peoples of the region waged war for three main reasons. They fought defensive wars to protect their territories from aggression and offensive wars to conquer new lands. They also fought civil wars, which involved internal rebellions or uprisings.

The earliest wars were disputes between small, loosely organized forces wielding hunting tools such as clubs, spears, and bows and arrows. Nomads* raided the fields and pastures of settled communities, whose inhabitants fought to protect their crops and livestock. City-states* fought for control of land and water resources. Over the course of several thousand years, the states of the Near East grew larger, stronger, and more centrally organized. In some cases, they developed into imperial* powers controlling vast territories. The fighting forces of these states and empires also grew larger and more organized, becoming ARMIES consisting of professional SOLDIERS with an array of WEAPONS AND ARMOR and commanded by ranks of officers.

With the development of large states and empires, wars were fought on a larger scale, and sieges*, fighting at sea, and multiyear campaigns in distant lands became commonplace. The centerpiece of warfare, though, remained the pitched battle, in which land armies maneuvered for position and then clashed on the battlefield.

Reconstructing Ancient Battles.

Modern historians have a difficult time reconstructing ancient battles. Surviving information about even the best-documented conflicts is often vague and incomplete. An example is a battle fought at MEGIDDO in the Levant*, which took place around 1456 B. C. This is the earliest Near Eastern battle for which detailed descriptions survive. Yet even the fullest account of the battle, which was recorded on the walls of the great temple of the god AMUN at KARNAK in Egypt, has many missing sections of text. Moreover, scholars realize that it was written in a literary style intended to glorify the achievements of the king. Many ancient accounts of battles were written for a similar purpose-to serve as propaganda*-making the accuracy of their information highly questionable.

The battle at Megiddo pitted THUTMOSE III, the ruler of Egypt, against a coalition of Canaanite forces. The surviving record gives many details of the Egyptian army’s long march to the city of Megiddo and its position on the day of battle on the Plain of Jezreel facing the city. However, it includes no details about the size or position of the Canaanite forces or about the actual fight. It says only that when Thutmose appeared on the battlefield, the enemy fled in great disorder.

The battle of Qadesh, in which the Egyptians fought against the HITTITES of ANATOLIA (present-day Turkey) around 1274 B. C., is known in greater detail because pictorial records accompany written accounts in Egypt. However, these pictures and texts fail to reveal that the Egyptians lost the battle. Instead, they focus on the bravery and heroism of the Egyptian king, RAMSES II.

Nearly all accounts of warfare in the ancient Near East contain no reliable information about such things as the location of battlefields, the weather and terrain in which a battle took place, the size and position of troops, the duration of the fighting, and how armies coordinated the movement of people and supplies. In short, information gathered from surviving official accounts of military encounters gives a broad picture of ancient warfare, but it lacks the details that would allow historians to reconstruct those battles.

Siege Warfare.

According to ancient texts, the battle of Megiddo was followed by a siege of that city. The ancient armies of the Egyptians, Hittites, Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians often employed siege warfare, which developed into a highly specialized form of combat with its own tools and weapons.

Siege warfare was a way of capturing cities or fortresses that could not be taken quickly in battle. Fortresses and many ancient Near Eastern cities had strong walls and other fortifications to help them withstand direct attacks by an enemy. During a siege, however, such protective barriers could become like the walls of a prison, trapping the defenders inside the city or fort.

An attacking army laid siege to a city by surrounding it with troops to make sure that no one could enter or leave. The defenders inside the city could neither send messages to allies asking for help nor obtain fresh supplies or reinforcements. Their ability to endure a siege depended on the quality of their fortifications and the soldiers who operated them, their stockpiles of food, and their access to freshwater from wells or streams.

The attackers in a siege had three ways to assault a besieged city or fortress. They could dig tunnels under the walls, climb over them, or smash and burn their way through them. If these methods failed, they co seal off the city and try to starve its inhabitants until they surrendered. Usually, attackers used some or all of these methods at the same time.

Tunneling under city walls required no special equipment other than shovels. Climbing over the walls required the construction of ladder or towers. The attackers might also build huge ramps of earth leading up to the top of the enemy walls. Sometimes these ramps had to cross streams or water-filled ditches that helped protect the approach to the walls.

Attempts to break through walls usually centered on gates, often made of wood, which were the weakest points in the walls. Attackers might try to set the gates on fire or break through them with a battering ram a, huge log or wooden beam mounted in a wheeled frame. Using ropes or chains, the attackers drove the ram as hard as possible against the gates or possibly the walls themselves. If the ram succeeded in making a hole in the defenses, soldiers would charge through to attack the defenders inside. Another tactic involved shooting flaming arrows into a besieged fort or city, hoping to start fires that would cause the inhabitants to panic, flee and surrender.

It was not easy to carry out siege operations under watchful eyes of the defenders, who could shoot arrows or hurl stones, hot liquids, or fire from the top of the walls onto the enemy below. Moreover, sieges took time, during which the attacking force also need food and other supplies. When these ran short, the attackers suffer from hunger and disease almost as much as the defenders inside the besieged city. The capture of an enemy capital or sacred city had great psychological impact on both the victors and the vanquished. Because siege warfare was so difficult and costly, it tended to be undertaken only as a last resort.

Bribery, treachery, or trickery occasionally offered attackers a way into a besieged city. A well-known example of this appears in the Iliad, the epic by the ancient Greek poet Homer, which tells the story of the long siege of TROY in Anatolia by the Greeks. After many years of siege, the Greeks built a giant wooden horse and a small band of soldiers hid inside it. When the Trojans hauled the horse into their city, the Greeks came out of the horse at night and opened the city gates to their armies.

Military Tactics.

Warfare involves strategies, which are overall goals, and tactics, which are the means used to reach those goals. The societies of the ancient Near East used different combinations of tactics to achieve their military strategies.

The military history of Assyria illustrates a shift from defensive to offensive strategies and the use of a wide range of tactics, including psychological warfare. At the beginning of the second millennium B. C., the city-state of ASHUR in northern MESOPOTAMIA slowly built a fighting force to defend itself. The rulers of Ashur, believing that their state had to conquer or be conquered, raided surrounding regions that threatened to attack.

Plunder proved to be an added advantage to Assyrian raids, and greed became a motive for further campaigns. Another motive for warfare was the growing desire of Assyrian kings to gain prestige through successful military campaigns. By 700 B. C., Assyrian armies had waged offensive wars from the Mediterranean Sea in the west to the Persian Gulf in the south. Campaigns usually began in the spring and lasted through the summer.

The Assyrians made little use of NAVAL POWER in warfare. Because they did not have a navy, they usually used Phoenician ships when they had to go to sea. They made extensive use of pitched battles and siege warfare, but these tactics consumed much time, energy, and labor. The Assyrians came to prefer psychological warfare, which involved breaking down the enemy’s will to resist. Once the Assyrians decided to conquer a region, they would try using diplomacy to get the inhabitants to submit. If diplomacy failed, they surrounded the foreign capital and shouted to its inhabitants, urging them to surrender. The next step was to attack small, weak cities and commit extreme acts of destruction and cruelty as a warning to all who did not submit. Using such methods of psychological warfare, the much-feared Assyrians made some conquests with minimal effort.

During the second millennium B. C., the Hittites of Anatolia had a well-organized and efficient military force that protected their borders and earned them a place among the great powers of the day. The Hittites used sentries, outposts, and spies to gather information about enemy movements. Sometimes Hittite agents disguised as deserters or fugitives deliberately passed false information to the enemy, a tactic that contributed to the victory of the Hittite king Muwattalli II over Ramses II of Egypt at the battle of Qadesh in about 1274 B. C.

The Hittites, just like others in the ancient Near East, believed in seeking guidance from the gods on military matters. The king might ask the gods if they approved of a campaign and if the king would win. He might even ask the gods to approve specific tactics and plans of action. The Hittites favored direct attacks and pitched battles. One favorite tactic was to burn crops and villages in an area until the men of the district were forced to fight the Hittite army. Another was to destroy one town in the hope that neighboring towns would submit without a fight. If a city did not submit and could not be taken by storm, the Hittites mounted a siege. Evidence suggests that, on occasion, a duel between two champions, one representing each side-for example, between David, the Israelite, and the Philistine Goliath; or between Achilles, the Greek, and Hector, the Trojan-might settle an issue. Such contests represented warfare in its most basic form.