Guderian’s potent army Guderian now had four mechanised divisions under his direct command: the 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions and the 2nd and 20th Motorised Divisions. It was an extremely potent force, made more effective because Bock allowed Guderian a free hand both tactically and logistically. As it was not tied down to the slow pace of infantry supply lines, XIX Corps could act as a fully independent mechanised army – the first such force in the history of warfare. For Guderian, it was the ideal weapon to maintain the German invasion’s momentum.

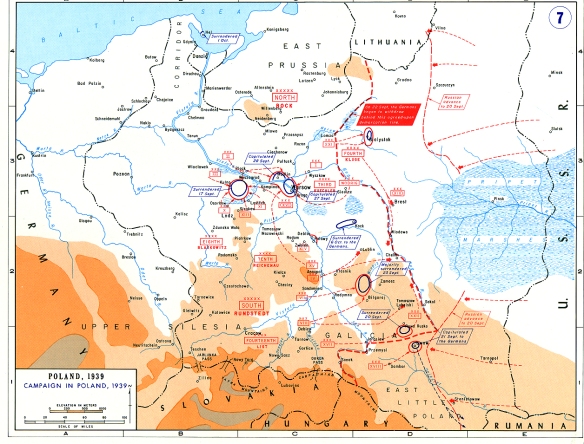

Having smashed through the Polish army’s cordon defence during the first two to three days’ fighting, Army Group South prepared to exploit its victory. In the centre of the advance, Tenth Army’s mechanised divisions began to race ahead of the infantry formations, bypassing strong points and the masses of Polish infantry streaming back towards Warsaw. To the dismay of the Polish high command, Germany’s panzer forces were invariably ahead of the retreating Polish infantry, thereby preventing the Polish commanders from having sufficient time to reorganise their battered forces.

Following behind, or sometimes alongside the panzers, were the combat engineer units whose responsibility was to remove obstacles, dismantle booby traps and build bridges. The Poles had anticipated that the German advance would be slowed by the many wide rivers that ran through their country, but German combat engineers were past masters at constructing pontoon bridges. One such engineer was Paul Stresemann. Although a reluctant soldier, his background in construction led him to be posted as an engineer officer, which ensured that he would be in the forefront of the advance when rivers needed to be crossed.

The Pilica River was crossed on 5 September, and the Tenth Army began to wheel around in a northeasterly direction towards Warsaw and the Vistula. At this point the Germans received reports that the Polish army was frantically attempting to organise a new army based around Radom (due south of Warsaw). The army was being assembled from various sources, including troops from the retreating Cracow Army and from the general reserve provided by the Prusy Group.

Encirclement at Radom

Rundstedt instructed the Tenth Army’s commander, General Reichenau, to envelop the Polish forces around Radom from the north, south and west. Reichenau’s intention was to destroy this last major concentration of Polish forces that lay between the key German objectives of Warsaw and the Vistula. Three army corps (IV, XIV and XV) were assigned to the battle which began late on 8 September. The Poles fought with determination, but the better-armed and better-trained Germans relentlessly ground them down with air support from the Luftwaffe. On 11 September, Radom was captured along with 60,000 Polish prisoners of war (although a few Polish units managed to break out to nearby forested regions where they continued resistance for several more days).

While the battle for Radom was in progress, panzer units of the Tenth Army reached the Vistula and secured the vital bridgehead at Pulawy on 8 September, and later at Gora Kalwarja. The hopes by the Polish high command of establishing a defensive line on a major river had been dashed once again. When the German infantry had caught up with the tanks (which were temporarily immobile due to fuel shortages), then the panzers would be clear to resume operations east of the Vistula.

The honour of reaching Warsaw fell to General Reinhardt’s 4th Panzer Division. Reinhardt’s tanks had reached the outskirts of the Polish capital late on 8 September, and an assault was ordered for 0700 hours the following morning. Supported by divisional artillery, the German tanks began to drive into the city, but Polish resistance was fierce, and after three hours’ fighting – with the advance completely stalled – the order was given to retreat. The Germans had learnt the dangers of using unsupported armoured units in built-up areas the hard way.

Polish countermoves.

To the south, the Fourteenth Army captured Cracow on 6 September, and, following a reorganisation of the army’s mobile formations, the mechanised XXII Corps advanced eastwards across the River Dunajec to cut off those Polish units escaping to the east of the Vistula. On 9 September, OKH instructed XXII Corps (followed by the rest of the Fourteenth Army) to break through the defences on the River San and wheel northwards towards Chelm with the final aim of making contact with Guderian’s XIX Corps advancing southwards from East Prussia. Thus, XXII and XIX Corps would become the two pincers conducting the encirclement of the Polish army east of Warsaw.

The German Eighth Army – on the Tenth Army’s northern (left) flank – was also making good progress and closing on Lodz. As a consequence, its own left flank was becoming dangerously exposed, especially from the Polish Poznan Army (directly to the north). German frontier units were assigned to protect the Eighth Army’s exposed flank and were later reinforced by two reserve infantry divisions to form Group Gienanth. But the potential threat posed by the Poznan Army was not fully comprehended by either OKH or the advancing Germans. While the frontier battles were raging along the Polish border, only the Poznan Army, commanded by General Kutrzeba, had not been fully engaged; the German planners at OKH had decided to bypass this force in favour of swift penetration into the heart of Poland. Once the nature of the German advance had become clear to the Poles, Kutrzeba requested the Polish high command for permission to attack the Eighth Army advancing eastwards below his southern flank. The request was refused as Marshal Smigly-Rydz was determined to get as many troops back behind the Vistula as possible, and so the Poznan Army began a long retreat eastwards towards Warsaw, attacked by the Luftwaffe but without interference from German ground forces. Meanwhile, remnants of the Pomorze Army were also retreating towards Warsaw, the two armies meeting up around the road and rail junction at Kutno, roughly half way between Poznan and Warsaw.

On 8 September, Kutrzeba again requested permission to attack the Eighth Army, using both the Poznan and Pomorze Armies. This was a substantial and still largely intact body of troops, consisting of ten infantry divisions and two-and-a-half cavalry divisions. Although any attack would delay the eastward retreat, the Polish high command was in a desperate position, its troops constantly being overrun by the German panzers. They reasoned that a major counter-attack might slow the advance of Army Group South in general, thereby allowing other Polish forces a breathing space, with time to retreat and regroup. Accordingly, permission to attack was finally granted.

Group Gienanth, originally responsible for the protection of the Eighth Army’s flank, had been left behind by the speed of the main German advance. As the Eighth Army neared the River Bzura, its flank guard consisted primarily of the 30th Infantry Division, which was spread out along a front of 20 miles and in no position to mount a coordinated defence. The Polish counter-attack was launched on 9 September, southeast across the Bzura, the only major offensive conducted by the Polish army during the campaign. The next day, the German 30th Infantry Division reported back to Eighth Army Command that it was under attack, suffering heavy casualties and was being forced backwards. Throughout 10/11 September, the Battle of the Bzura raged with great intensity. Although the Poles had managed to force the Germans back, they were short of food, ammunition and other military supplies. One Polish officer engaged in the fighting explained some of the special problems facing him and his men:

There were dead Germans lying everywhere, on the road and in the ruined buildings. I gave my men orders to go through the Germans’ map and trouser pockets in the faint hope of finding the maps which we needed so desperately. At last our search was rewarded: we found a map of the Brochow-Sochaczew area in the pocket of a dead NCO. For us that was the most valuable booty of the entire war.

The Polish counter-attack across the Bzura had come as a surprise to the Eighth Army, but there was no panic and orders were issued to contain the Polish attack. At the headquarters of Army Group South, Rundstedt and his chief of staff, Manstein, saw the Polish attack not so much a problem, but more an opportunity to fulfil the original OKH plan of destroying the Polish army west of the Vistula.

By now, approximately 170,000 Polish troops were concentrated around Kutno. If they could be encircled, contained and destroyed, then the Polish army would have lost over a third of its ground forces at a stroke.

German redeployment

The redeployment of the German army to deal with the Polish counter-attack was a masterful display of the ability of German general staff officers to move large, complex forces with economy and swiftness. On 11 September, General Blaskowitz was given control over the operation and was assigned formations from both the Tenth Army to his right, and from the Fourth Army advancing from the north. The Eighth Army had doubled in size almost overnight and had six corps working under a single command. One consequence of the coming battle was that the pressure on the Poles in Warsaw was temporarily eased, while German operations on the Vistula were also scaled down.

On 12 September, General Kutrzeba was informed that the remnants of the Lodz Army were retreating towards Modlin, and that any hope of their forces meeting up was no longer feasible. More ominous still were the manoeuvrings of the German forces around Kutno, which threatened the Poles with encirclement. Kutrzeba was in danger of being trapped. On 12 September the Poles attempted to break out of the encirclement with an offensive to the southeast. The Germans lost some ground but the ring held firm, and by the 15th the Polish attack had been exhausted. On the same day, the German Tenth Army was ordered to advance northwards to the west of Warsaw to block off any escape route from the Kutno pocket towards the Polish capital.

The Poles made a further attempt to break out on 16 September, to the northeast, in the hope of crossing the Vistula and reaching Modlin. The attempted break-out was once again repulsed, with heavy Polish casualties. The fighting enabled the Eighth Army to further tighten its grip on the Kutno pocket, the Polish troops being compressed into an ever smaller area, which in turn made them highly vulnerable to aerial attack. On 17 September, the Luftwaffe broke off its bombing operations against Warsaw to concentrate all its efforts against Kutno. The trapped Poles suffered heavy losses as 328 tons of bombs rained down upon them in the pocket.

The Polish defences began to collapse during the 17th: 40,000 men were captured by the Germans on that day, and one last break-out attempt by two Polish divisions was crushed by Tenth Army guarding the approach to Warsaw. The only troops to escape were in small units, most slipping away through the cover provided by the Kampinos forest. Increasingly, the Polish army was breaking down into isolated groups capable, at best, of only guerrilla operations.

German respect for the Poles

Although Hitler had reprimanded his generals when the Poles managed to slow the advance towards Warsaw, for the German high command, the battle of the Bzura was a monumental success, one that even surpassed Hannibal’s victory at Cannae – a battle that Prussian staff officers had studied for decades as the benchmark of military triumph. For the ordinary German soldier it had been a tough engagement. Kurt Meyer, later a general in the Waffen-SS but then a junior officer in the SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler, had fought in the battle attached to the 4th Panzer Division. Despite being a fanatical Nazi, Meyer paid his respects to the Polish soldier: ‘It would not be fair on our part to deny the bravery of the Polish forces. The battles along the Bzura were fought with great ferocity and courage.’

While the Poles in the Kutno pocket were still fighting, the Polish high command fell back on a last expedient: the general retreat of all forces towards the southeast of Poland to form the ‘Romanian bridgehead’. Although the German Fourteenth Army had been pressing directly eastwards along the northern edge of the Carpathians, southeast Poland was the last area where a new line of resistance might be formed, centred around Lwow and the oil-rich region bordering Romania and Hungary.

In the northern theatre of operations, the Polish Modlin Army and the Narew Group began to retreat on the night of 9/10 September, closely followed by the German Third Army. On the Third Army’s eastern flank, Guderian’s XIX Corps exploited the gap opening up between the two Polish formations. A counter-attack by the Narew Group was repulsed with the Poles suffering heavy casualties. The two panzer and two motorised divisions of XIX Corps were suffering from shortages of fuel and ammunition, and the wear and tear of campaigning was beginning to take its toll of the armoured vehicles, and yet Guderian’s miniature ‘panzer army’ still had the firepower and mobility to overwhelm virtually anything it encountered.

Although Guderian wanted his tanks to operate in a drive east of the River Bug towards Brest-Litovsk, OKH still remained cautious of committing its armoured forces so far east. The original plan was for Guderian to drive south to Siedice, but OKH’s realisation that the Poles were attempting to form their ‘Romanian bridgehead’ forced a change of mind. Guderian was now allowed to follow his preferred plan to drive southwards along the east bank of the Bug, which would eventually enable him to outflank this last Polish defensive line.

On 14 September, advance units of the 10th Panzer Division reached the edge of Brest-Litovsk, Army Group North’s most easterly objective. The following day, the city was captured, although the Polish defenders retired into a fortification known as the Citadel. There they repulsed several more German attacks from the 10th Panzer and 20th Motorised Infantry Divisions. But on the 17th, as the Poles were attempting a break-out, German infantry finally secured the Citadel. The 3rd Panzer Division moved southwards to Wlodova, in the expectation of meeting up with advance panzer units driving northeast from Army Group South.

Although the two great pincers that trapped the Polish forces to the east of Warsaw did not meet physically, they remained only a few kilometres apart, maintaining contact through radio – a fitting tribute to a communication device that had been so important in the success of the German mechanised formations. Actual contact occurred in the original pincer movement towards Warsaw, when elements of the two army groups met at the Vistula bridgehead at Gora Kalwarja, just south of the Polish capital.