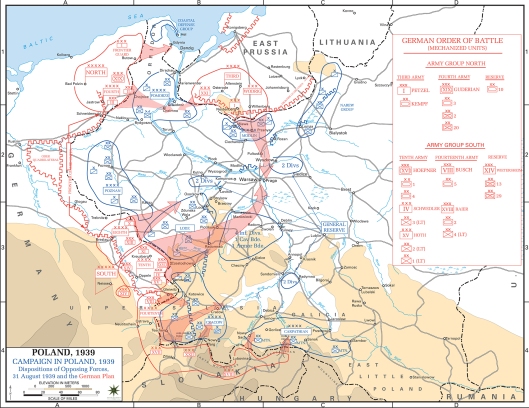

Caught by surprise by the Nazi-Soviet pact, the Poles resisted valiantly as the two powers seized their homeland. For Europe, it was the first opportunity to witness the blitzkrieg in full effect.

At 0440 hours on 1 September 1939, German aircraft of the Luftwaffe bombed air bases in Poland. Five minutes later, German ground forces rolled over the border into Poland, while the old German battleship Schleswig-Holstein emerged from the early morning mists and started shelling the Polish fortress on Westerplatte. World War II had begun.

The first fatality of the war had, in fact, occurred the previous evening when a German concentration-camp prisoner was murdered by an SS commando unit during a staged attack on a German radio station at Gleiwitz near the Polish border. Organised by the Gestapo chief, Reinhard Heydrich, the raid was a German attempt to provide some kind of justification for Hitler’s unprovoked attack on Poland.

A small group of SS men, dressed in Polish army uniforms, attacked the isolated transmitter, fired shots into the air and took over its running. Listeners to the station heard the shots and a voice, speaking in Polish, declare: ‘People of Poland! The time has come for war between Poland and Germany. Unite and smash down any Germans, all Germans, who oppose your war!’ To complete the charade, the unfortunate concentration camp inmate who had been forced along by the SS troops and dressed in civilian clothes to look like a radio operator – was shot and his body left at the scene of the attack for later inspection by the world’s press. The following day, Hitler proclaimed a state of war between Germany and Poland, citing the Gleiwitz incident as one of the reasons for the invasion.

Although the Polish high command had ordered a general mobilisation on 30 August, the German invasion still came as a surprise. Many Polish reservists had yet to reach their units, and many of these units were in the process of moving to their mobilisation areas when the German maelstrom struck. The invaders soon swept aside the Polish frontier troops, and during the late afternoon of 1 September they began to make contact with forward elements of the Polish army.

The Luftwaffe strikes

Meanwhile, the Luftwaffe had been in action in earnest. The initial task for the German air crews was the destruction of the Polish air force on the ground. All the major bases were heavily bombed, as were air strips in the regions where German advances were expected. Some Polish aircraft did manage to get airborne, but they were either shot down or driven off from the German areas of operation. The old fighter aircraft fielded by the Poles were hopelessly outclassed by the Messerschmitt Bf-109s of the Luftwaffe. Low flying German aircraft reported that Polish light anti-aircraft and small arms fire was fairly accurate, but at medium and higher altitudes the Luftwaffe could operate with relative impunity.

Despite a belief to the contrary, the Polish air force was not destroyed in the first day of fighting, and it continued to mount operations as best it could. The fighter defences over Warsaw continued to offer resistance for three days, and fighter patrols flew over Silesia and Bohemia-Moravia, while a bombing mission was made against East Prussia. But by 3 September, the Polish air force had ceased to exist as a coherent force, and from then on the German bombers had a virtual free hand over the whole of Poland.

Once the Polish air force had been dealt with, the Luftwaffe could concentrate on ground targets. Particular emphasis was paid to the destruction of road and rail bridges, rail heads and other forms of communication. Subsequent bomber waves attacked administrative and industrial centres, and the masses of Polish troops attempting to fend off the German ground invasion faced near constant bombardment from the air. Attacks on civilian targets were not neglected, and Warsaw was heavily bombed on the first day of war. Central to the German blitzkrieg philosophy was the spread of fear and confusion among the general population, and the long columns of refugees fleeing into central Poland were too easy and tempting a target for the air crews of the Luftwaffe to resist (although, in fairness to the Germans, it was often difficult to distinguish between evacuees and legitimate military targets).

The two armies of Army Group North found their operational areas shrouded in mist during the early morning of 1 September, which aided concealment but caused some early confusion with units firing on each other. The German Fourth Army drove directly eastwards from Pomerania to cut off the Polish Corridor, while the Third Army divided its forces between an attack southwestwards (to link up with the Fourth Army in the corridor) and a drive southwards towards the Polish capital. Further north in the corridor, Danzig was secured with little resistance by a brigade of German infantry, although Polish strong points along the Baltic coast continued to offer resistance.

Rapid German success

Spearheaded by General Heinz Guderian’s XIX Panzer Corps, the German Fourth Army met only limited resistance during the first day of the invasion. The German command believed the Poles would fall back to the River Brade and there establish a defensive line, but on 2 September German tanks crossed the Brade with minimal opposition. The only problem occurred when tanks of the XIX Corps ran out of fuel and ammunition, and were stranded for a time behind what remained of the Polish front line.

The advance of Army Group North had gone almost like clockwork – a tribute to the excellence of German staff work. For the troops at the cutting edge, however, the experience of combat for the first time could cause problems. FW Mellenthin, then an intelligence officer in General Hause’s III Corps with the Fourth Army, described one such incident:

Very early in the campaign I learned how ‘jumpy’ even a well-trained unit can be under war conditions. A low-flying aircraft circled over corps battle headquarters and everyone let fly with whatever he could grab. An air-liaison officer ran about trying to stop the fusillade and shouting to the excited soldiery that this was a German command plane – one of the good old Fieseler Storke. Soon afterwards the aircraft landed, and out stepped the Luftwaffe general responsible for our close air support. He failed to appreciate the joke.

The surprised troops of the Polish Pomorze Army were only able to mount sporadic resistance against the relentless German assault. In one such engagement (1 September), a unit of German infantry was charged by mounted troops of the Polish 18th Lancer Regiment. During the fighting, the Poles suddenly found themselves outflanked by German armoured cars which inflicted heavy casualties on the Polish cavalrymen, forcing them to retreat in disorder with the loss of their commander, Colonel Mastalerz.

This incident formed the basis of the legend of Polish lancers attacking German tanks. Later in the campaign, there were a number of actions where mounted Polish troops became involved in fighting with German infantry, and in other instances German tanks attacked Polish cavalry units. Although the Poles had a reputation for reckless courage, their officers were not so foolish as to knowingly commit flesh and blood directly against hard steel. But given the nature of national stereotypes, the story swiftly gained wide credence.

Spirited Polish defence

The German Third Army’s advance towards Warsaw was briefly halted by troops of the Modlin Army, holding defensive positions in the Mlawa area. The Poles resisted for three days until a German outflanking movement forced a withdrawal southwards. The troops appointed to the other area of operations assigned to the Third Army – the westwards drive into the Polish Corridor – met fierce resistance around Graudenz, a town on the Vistula, while further north the key bridge over the river at Dirschau was destroyed by the Poles. Fortunately for the Germans, their armed forces had long experience in the use of pontoon bridges, and the Vistula was promptly bridged at Meve.

On 3 September, Third and Fourth Armies met at Neuenberg, trapping Polish forces in the north of the corridor. At the same time, the Germans began to push back what remained of the disorganised Pomorze Army towards Bromberg. The city of Bromberg had a large German population, and when news of the invasion reached the German community, there was an uprising. Polish troops and other Polish inhabitants put down the uprising with considerable bloodshed, an incident which received wide coverage in the German press and broadcasting services.

The old animosity between Poles and Germans re-emerged in this campaign, and was stoked-up by Hitler and the Nazi propaganda machine. A week before the invasion, Hitler had harangued his senior generals with the details of how he would send SS units into Poland ‘to kill without pity or mercy all men, women and children of Polish race or language’. Hitler’s hatred of the Slav peoples would ensure that the war in the East would be fought with the utmost severity.

During 4 and 5 September the remnants of General Bortnwoski’s Pomorze Army began to retreat back towards Warsaw. For the first time in three days the exhausted Polish troops were not harried by the Germans. The bulk of the German Fourth Army was redeployed eastwards, instead of following the Poles along the plain of the Vistula, and began an advance into East Prussia behind the advancing formations of the Third Army, driving on Warsaw from the north and northwest.

General Rundstedt’s Army Group South was responsible for the destruction of the Polish armies across the Silesian border and the seizure of Warsaw from the south. The sky during morning of 1 September was clear over southern Poland, and German reconnaissance aircraft had little difficulty in picking out the long columns of German troops crossing the border. In the centre was General Reichenau’s Tenth Army, whose seven mechanised divisions (followed by six infantry divisions) made it the most formidable of the various armies attacking Poland, and reflected its key role in leading the German advance on Warsaw. Protecting the Tenth Army’s left flank was the Eighth Army, whose own objective was the capture of Lodz. On the right of the German advance was the Fourteenth Army, which protected the southern flank of the invading forces as well as being assigned the responsibilities of overrunning Cracow and the industrial regions of Galicia.

Continued German success Advance elements of Army Group South penetrated up to 15 miles into Poland on the first day of hostilities. Among the lead units to cross the border was a reconnaissance company of the 2nd Light Division (Fourteenth Army) led by Hans von Luck. He described the ease with which the Germans advanced into Poland:

We fell in with the armoured reconnaissance regiment. The frontier was manned by a single customs official. As one of our soldiers approached him, the terrified man opened the barrier. Without resistance we marched into Poland. Far and wide there was not a Polish soldier in sight, although they were supposed to have been preparing for an ‘invasion’ of Germany.

The following day, however, resistance increased and the German advance slowed. The Polish army hoped to form a defensive line along the River Warta and southwards to Tschenstochau, but the confusion caused by the surprise and power of the German attack made such an undertaking impossible. Early on 3 September, Tschenstochau was taken by the Tenth Army, and German mechanised units secured bridgeheads over the Warta. To the south, the German Fourteenth Army commenced its drive on Cracow, while additional mountain units began to debauch from the high passes in Slovakia’s Carpathian Mountains, thereby outflanking forward Polish units defending Cracow.

General Polish withdrawal

Aware that both the southern and northern fronts were in danger of total collapse, the Polish high command issued orders on 5 September to begin a general withdrawal towards the Vistula, which was modified the following day to the adoption of a new defensive line running from the Narew river in the northeast, along the Vistula and back along the River San. Marshal Smigly-Rydz had to face the fact that the battle for the frontiers had been a total disaster, and his only hope was to withdraw as many formations as possible to the relative safety of eastern Poland before they were destroyed piecemeal by the marauding panzer columns and Luftwaffe. The first three days of combat had come as a sickening blow to the Polish high command, and help from Poland’s allies in the West had become ever more vital if the Polish state was to survive at all.

The French ‘invade’ Germany

As a token gesture, French troops advanced into German territory in the Saar region on 7 September. The advance was slow and careful; casualties were avoided and German frontier troops fell back in good order. The French had advanced a mere five miles by the 12th when the Saar ‘offensive’ was called to a halt. There the French adopted a defensive position until withdrawing all their forces on 4 October. Although the Polish high command held the realistic expectation that help from the Allies would not come in a few days but take several weeks, the inactivity of France and Britain in September 1939 was a bitter pill to swallow.

The declarations of war by Britain and France did, however, have consequences for future German strategy in Poland. The planners at OKH were fearful that the Allies might launch an attack in the west, and consequently were reluctant to send large numbers of troops deep into Polish territory. OKH argued that if the Allied attack did materialise, then Germany’s elite formations would have to be transferred westwards as quickly as possible. By contrast, the German commanders on the ground wanted to develop the encirclement of Polish forces well to the west of Warsaw.

In keeping with this idea, General Bock, commander of Army Group North, intended to redeploy the Fourth Army through East Prussia to new positions on the left (eastern) flank of the Third Army to prevent the Polish army from adopting new defensive positions east of Warsaw. It was an imaginative proposal, but OKH considered it to be too risky in the light of the new threat to the Germans’ rear in the west, and accordingly vetoed the plan. In the debate that followed, a compromise measure was adopted, and on 5 September OKH permitted a reinforced XIX Corps, led by Guderian, to make the crossing through East Prussia and attack the Polish forces behind the River Narew. The remainder of the Fourth Army would resume its role of pushing the Poles back towards Warsaw on the right bank of the Vistula.