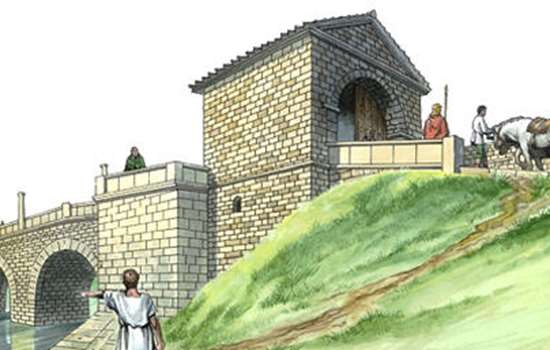

Hadrian’s Wall; Chesters Bridge Abutment

Despite the remaining fortifications that surrounded them, the Europeans of the Germanic West had difficulty reaching the level of defensive sophistication of the Roman Empire. Even with the extant physical reminders of the Roman fortified lines, especially Hadrian’s Wall in Britain, they declined to maintain such lines and delayed a long time building their own. Perhaps they saw little point to such defenses, which had failed to keep them out of the Roman heartlands. The permeability of such zones has raised a number of debates as to their real purpose, and whether they were meant to prevent invasion, to slow invaders, or to keep internal populations within limits. The Saxons, who invaded Britain after the 450’s, found the defenses of the Saxon Shore did little to slow their conquest. To the north Hadrian’s Wall likewise hindered the Picts little in their raids.

Hadrian’s Wall stretched for 117 kilometers across northern England, ranging in thickness from 2.3 to 3meters and averaging a height of from 5 to 6meters. The wall was part of the Roman strategy of defense in depth. In the absence of manned watchtowers and fortified camps to the rear, the Saxons were hardly set to use the wall to its best advantage. Even so, the wall did form, in its less than pristine state, something of a hindrance to the return of raiders northward. Northumbrian pursuers could count on it slowing marauders if those raiders tried to get their spoils through or over the fortifications.

It would appear that Offa’s Dyke, built during the reign (757-796) of that Mercian king, was meant to achieve an effect along the Welsh border similar to that of Hadrian’s Wall. An earthen rampart 18 meters wide formed in part by the ditches that bracket it, Offa’s Dyke meandered for 192 kilometers through regions that had little in the way of leftover Roman defenses or roads. There was little hope of keeping out Welsh raiders, especially since the dyke was virtually unmanned. Again, though, its physical bulk would slow the exodus of such raiders, especially if they were driving stolen livestock, permitting Mercian forces to catch up with the marauders. In addition, the dyke provided a roadway that cut across the ranges and rivers of the Welsh marches, thus easing both the report of such raids and the speed of reaction.

The impassability of terrain might make fortified lines not only a cost-prohibitive measure but also a rather unnecessary one. In Mesoamerica contending empires could keep invaders at bay simply by blocking well-established paths. In the absence of siege equipment and draft animals, such structures would not have needed much complexity to be effective. In Europe fortified bridges developed not only to secure lines of communication and transport but also to block the progress of Viking raiders up the river systems. Thus a number of such bridges controlled the rivers below Paris after the 880’s to prevent direct access or indirect efforts by portage. When Vikings actually did besiege Paris in 885, it took them over four months just to reach the city.

The most famous and latest of all fortified lines are of course those of China. The Great Wall is not actually a single wall curling along China’s northern borders, nor does its current condition date back to 221 b. c. e. The earliest (Qin) walls were earthen, tamped down by forced labor between retaining wooden walls that connected watchtowers. The actual remains of this wall are now in the realm of conjecture. The current masonry walls-which are actually many sets of walls, not always connected, and not one continuous line-date from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) emperors, who reigned after the expulsion of the Mongol Dynasty. The facts of these fortifications are impressive: 2,400 kilometers in length, 7.6 meters high at a minimum, often 9 meters wide, and sometimes scaling 70-degree slopes. Like their European counterparts, however, they proved less than impermeable, again raising the question of whether the walls were more clearly intended to keep the native population contained within and untainted by exterior contact.

As the Germanic groups, especially the Franks, entered the deteriorating Roman Empire, they brought a new structure to the landscape: the private fortress. Although these small refuges, which utilized so little stone, have left few archaeological remains, contemporaries noted their appearance in rural and isolated areas. Most important, commentators of the day stressed the remoteness or inaccessibility of such sites. Because of the new inhabitants’ rudimentary technology, these protocastles relied on their physical surroundings to deter would-be invaders. On isolated summits, crowning precipitous sites, these forts gave some protection to the rural regions of Gaul and Visigothic Spain; their small size and private ownership, however, limited their value as refuges for a harried populace. Instead, the later Frankish kings found them to be troublesome centers of resistance, because it was so difficult to bring an army to bear on such places.

The situation differed in eighth and ninth century Anglo-Saxon England, especially Wessex. By the 870’s, after Viking invaders had occupied much of England and pushed into Wessex, King Alfred the Great (r. 871-899) secured a truce after his victory at Edington (878). During the cessation of active campaigning, Alfred devised a sophisticated defensive strategy centered upon thirty-three refuges. These burhs, as they were called, were scattered over the kingdom, seldom more than a day’s ride apart, and usually near major transportation routes. Often quite sizable and well provisioned, the burhs were meant both to house a large garrison and to provide ample room into which a refugee population might flee. Alfred’s strategy, which would prove successful in 896, was to have the population and movable wealth protected in the burhs while he shadowed the invading Vikings with the Wessex army. By hampering the Vikings’ ability to forage or pillage, Alfred simply made his kingdom an uninviting prospect to Viking plunderers.

These fortifications did not have to be terribly complex, because the Vikings had little in the way of siege weaponry. Nonetheless, Alfred’s administration prepared the burhs well, as is known from a document called the Burghal Hidage (c. 920), which lists them. By dividing the resources of the kingdom into units called hides, each of which was sufficient to provide one man for burh garrisons, the Anglo- Saxons assigned enough hides to each burh to assure that its walls were defended by one man for every 1.3 meters. Because some burhs had circumferences of over one mile, this meant that Viking invaders had to sense the sizable numbers of uncowed foes they left in their wake as they bypassed the burhs. The burhs themselves were formidable: The first barrier was an exterior ditch perhaps more than 30 meters wide and sometimes as deep as 8 meters; an earthen bank came next, reaching up to 3 meters in height; timber defenses surmounted this ringwork in most cases, but stone walls were put in place at major sites, especially those that housed the royal mints. Many burhs took advantage of natural defenses, such as swamps and rivers, whereas others were built upon the remains of previous Roman fortifications.

The advantages offered by burhs or even the most simple defenses naturally drew people to those fortified locales. This rationale appears to explain the growth of the stone enclosures at Great Zimbabwe centuries later. The original impetus for the southern African plateau’s settlement remains debated, but the availability of iron doubtless held part of the appeal. At all three parts of the site, the most restricted sites are those where archaeology has found iron stores or iron-working tools. Between 1100 and 1500, the Great Enclosure was built, with walls of quarried granite about 10 meters and without any mortar, encompassing first a hilltop and later a site across a small valley. Early in the twentieth century, the archaeological record at Great Zimbabwe was greatly altered or nearly destroyed, and the reason for the site’s abandonment by 1700 is unknown. However, no one has supposed a victory by besiegers.