Ironclad Ram Affondatore (1866)

The fog of gunsmoke and the confusion of battle are better rendered in this canvas by Alex Kircher. Kaiser takes center stage in this panorama of the battle, apparently just after breaking the Italian line, with the Portogallo behind her and Austrian ironclads at left including Tegetthoff’s flagship.

By the late 1850s, the impact of the Industrial Revolution on navies and naval warfare brought the age of fighting sail to a close, albeit slowly. Steam propulsion, the screw propeller, armoring, shell guns, rifling, and iron and steel construction transformed the ship of war. Steam freed the warship from dependence on the wind, at first only in battle, but then gradually at the operational and strategic levels. The French launched their first armored steam warship—the la Gloire—in 1859. The British countered in 1861 with the Warrior, an iron-hulled, 400-foot-long, steam-driven man-of-war capable of fourteen knots and mounting thirty-eight 68-pounder naval guns.

During the American Civil War, the navies of the North and the South reflected the revolutionary changes overtaking naval establishments. The Federal navy continued to employ wooden sailing men-of-war, albeit outfitted with auxiliary steam power. The infamous Confederate raiders, such as the Alabama, likewise relied on their sails for cruising and steam as a combat auxiliary. The principle armament of these raiders, and the ships that hunted them, was massive, centrally mounted, rifled pivot guns capable of firing to port or starboard. For coastal defense, the South clad many of its wooden ships, such as the Virginia, with iron and dispensed with sails. The North countered with its own ironclads, as well as several classes of iron-constructed and -armored “monitors” that mounted heavy, muzzle-loading cannon in powered turrets.

This contest between the gun and armor placed a premium on penetration, not explosive power. To defeat armor, navies adopted ever-larger rifled cannon capable of hurling shot, increasingly designed to pierce armor plate, with greater range, accuracy, and penetrating ability. Rifling, in turn, led to longer barrels, which promoted a shift to breech-loading mechanisms in the 1860s.

During the decade after the American Civil War, the “modern” warship began to emerge. In 1872, the Italians launched the Duilio with armored decks and echeloned turrets. The following year, the British commissioned the Devastation, which established the basic pattern followed into the twentieth century.

As engagement ranges increased, sighting naval guns of different size became next to impossible. The chaotic patterns of splashes made the correction of individually sighted guns impractical. The solution involved salvo firing by batteries of uniform type, a development that led inexorably to the all-big-gun battleship—the most famous of which was the Royal Navy’s Dreadnought, launched in February 1906. The 17,900-ton ship mounted ten twelve-inch guns in its main battery and was the first man-of-war powered by steam turbines. The Dreadnought pattern remained unchanged for forty years.

The industrial age also wrought a revolution in ship types and tactics. Dreadnoughts replaced the wooden ship of the line; protected and armored cruisers took up the frigate’s role as commerce raider and scout. New types of light, fast, but deadly smaller ships milled about the battle line, waiting for the opportunity to disrupt and to weaken the enemy’s formation.

Central to this revolution was the self-propelled, or “automotive,” torpedo. In the late 1860s, the Englishmen Robert Whitehead refined an Austrian design and manufactured the first automotive torpedo. Until the development of effective internal combustion engines later in the century, the preferred means of delivering the new automotive torpedo was small, steam-powered surface craft termed “torpedo boats.” The ability of these smallish ships to sink a ship of the line, a capability lesser sailing-age warships had never possessed, added a new dimension to naval tactics. To screen the battle line, navies developed “torpedo-boat destroyers” and “light” cruisers, whose job was to counter the destroyers and which, armed with their own torpedoes, eventually supplanted the torpedo boats.

By the beginning of the Great War in 1914, navies had assumed a new pattern. Warships were steel constructed and steam driven. Dreadnoughts mounted long-ranged, rifled breechloaders, while new classes of smaller ships screened and scouted for the fleet.

The Industrial Revolution also dramatically changed strategic geography. Steam power shortened cruising radii: gone were the days of the six-month cruise under sail. Navies now needed overseas bases, particularly coaling stations, and this factor had a regressive impact on strategy and planning, and accelerated the centuries-old trend toward European imperialism. Because the new ships were more expensive, fleets became smaller. The Industrial Revolution also spawned a new European challenger to British naval supremacy, Germany, and two non-European centers of naval power—the United States and Japan.

At the tactical level, technology offered solutions to old problems while simultaneously presenting new threats. Dreadnoughts could cover their vulnerable bows and sterns and apply a substantial portion of their fighting power forward and aft, although commanders still arranged their fleets in a line-ahead formation to maximize firepower. Steam power eased the problem of maneuvering a fleet. Wider arcs of fire made crossing the enemy’s T a favored fleet tactic—one permitting a deadly concentration of firepower against the head of an enemy column in a manner impossible during the age of sail. But an enemy fleet armed with big guns, once within visible range, posed an immediate, rather than a potential, threat. While sea battles remained two dimensional (until the advent, later in the century, of effective submarines and aircraft), the presence of torpedo boats and destroyers made the first late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century naval encounters complex affairs. Every man-of-war possessed the capability to strike a deadly blow. The smallest and most inexpensive torpedo boat could sink the most powerful and costly dreadnought.

If the advent of the new industrial technology at sea increased the demands on naval commanders, that same technology offered few compensating advances in the area of command and control. At the strategic and operational levels of warfare, the telegraph revolutionized the contours of naval command and control. For the first time in history, the submarine telegraph offered admiralties, and the governments they served, the prospect of commanding and controlling fleets and squadrons operating on distant stations. But into the twentieth century, signal flags and doctrine remained central to fleet command and control at the tactical level.

The first major European test of the new tactics for steam-powered and armored ships came off the Adriatic island of Lissa on 20 July 1866, during the Austro-Italian War. The battle, the largest naval encounter since the 1827 battle of Navarino, was a confused affair from which naval officers drew few lessons.

The Italian admiral Count Carlo Pellion di Persano was a pusillanimous man who ranks as one of the worst commanders in the annals of naval history. He decided that the island of Lissa offered an excellent forward base for a blockade of the Austrian coast. Persano sailed south and reached the island on 17 July. He foolishly waited several days before cutting the telegraph cable that linked the island to the Austrian mainland. On 20 July, as Persano finally prepared to land his invasion force, one of his scouts appeared on the horizon making the signal for “suspicious” ships to the northwest. The Austrians, alerted by the uncut telegraph, had arrived.

While Persano’s force was the stronger, outnumbering the Austrians in every quantitative category, the Italians were in trouble. Their fleet steamed toward the southwest in line-abreast formation as the Austrians came into view, heading on a southeasterly course. Persano made the signal for his ironclads to reform into line ahead on a course toward the northeast—directly across the path of the Austrian fleet.

Rear Admiral Baron Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, a generation younger than Persano, commanded the Austrians bearing down on the Italian line. The Austrian commander was an aggressive man who, despite being outnumbered and outgunned, intended to bring on a mêlée. Tegetthoff deployed his ships into three successive wedges.

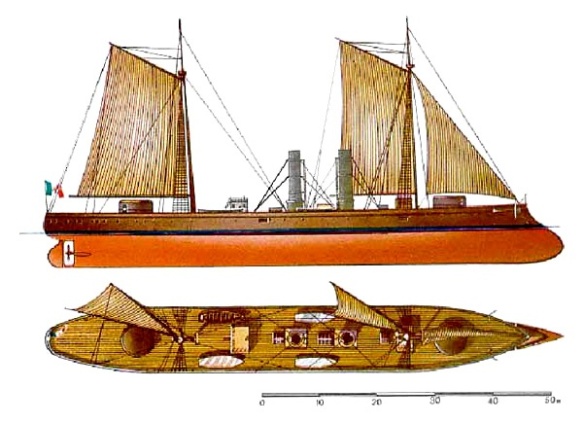

Tegetthoff’s decisiveness was matched by Persano’s vacillation. The Italian commander at the last moment decided to switch his flag from the Re d’Italia to the new British-built Affondatore, a powerful ship that carried two turreted 300-pounder muzzle loaders and a twenty-six-foot-long ram. As the Italian flagship, the fourth vessel in line, slowed to allow the transfer, the three ships ahead continued on course, while those behind the Re d’Italia reduced speed. As a result, a wide gap opened in the Italian line. Worse yet, Persano’s captains were unaware that their admiral had changed ships and continued to look to the Re d’Italia, from which Persano’s flag still flew, for signals that never came. Nor did the Affondatore carry a complete set of signal flags.

Tegetthoff did not rely on signals; he personally led his fleet. His flagship—the Archduke Ferdinand Max—was at the point of the leading wedge. As the Austrians bore down upon the Italian line, Tegetthoff made only two signals: “Ironclads, charge the enemy and sink him,” followed by “Ram everything gray!” Once the battle began, Tegetthoff trusted to the initiative of his captains.

About 1050 that morning the Austrians broke the Italian line, or, to be accurate, steamed through the gap created by Persano. What followed was a chaotic battle; smoke produced by the heavy guns and more than a score of steam-powered men-of-war cast a blackened pall that reduced visibility to, at best, 200 yards. Amidst the confusion, Persano steamed about in the Affondatore, signaling madly to subordinates intently watching the Re d’Italia.

After about thirty minutes of action, neither fleet had secured an advantage. Despite an excess of expended shot and shell, few ships were actually hit. The tide finally began to turn when the Austrians concentrated their attack against the rear of the Italian line. The old Kaiser, a ninety-two-gun wooden ship of the line, rammed the Re di Portogallo, shocking its crew, though not damaging the Italian ironclad. Under heavy Austrian gunfire, the Italian armored gunboat Palestro caught fire. Then Tegetthoff’s flagship rammed the American-built Re d’Italia, punching a hole in the side that in minutes sent the Italian flagship to the bottom, where it was soon followed by the Palestro.

Persano withdrew; the battle of Lissa was over. Tegetthoff, his fleet slower and weaker than the surviving Italian force, chose not to pursue. The Austrians had 38 men killed and another 138 wounded. The Italians lost two ships and suffered nearly 800 casualties, including over 600 dead.

The symbol of the battle of Lissa immediately became the ram bow. Because the Austrians won the day following the ramming of the Italian flagship, ramming became an accepted, and in some quarters the principal, tactic in naval warfare. Such tactics appear idiotic in retrospect; at Lissa the Austrians and Italians actually had little success ramming opponents under actual battle conditions. But the reality was that they had an even more difficult time sinking ships with gunfire.

The lesson that the gun had taken the measure of armor became evident during the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895. At the battle of the Yalu, 17 September 1894, the Japanese fought and won a long-range battle during which gunnery predominated.

Given the remarkable advances in the technology of warfare at sea, the practice of actual naval combat during the century that followed Trafalgar (1805) was too limited to draw many clear lessons, although a few trends were apparent. The tempo of the naval battle under steam was faster. The end of reliance on the wind for mobility, the marked increase in the speed of ships, and the ever-lengthening ranges of the big guns placed a premium on quick decision-making. Steam-driven and armored line-of-battle ships dominated, but no longer monopolized, the engagement. Torpedo boats and destroyers, while they had no place in the line, were important and deadly fleet assets. The era of “combined arms” had come to naval warfare. In the battles of the Russo-Japanese War, the largest of the era, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and torpedo boats played important roles in a contest in which a rising Asian power defeated a European empire.