Stuart’s absence from the Army of Northern Virginia had upon the outcome of the battle at Gettysburg. There is little doubt that even if Stuart had been with the army, a large scale battle would have been waged in Pennsylvania. Lee’s options were limited: fight or retreat. He could not remain in Pennsylvania indefinitely because his supply lines were too attenuated, and leaving the Confederate capital undefended for an extended period of time was politically and militarily inexpedient. Likewise, President Abraham Lincoln would not have permitted Lee to march at will across Pennsylvania unchecked for an extended period of time. Eventually, inevitably, sooner rather than later, the resources at Lincoln’s disposal would have been concentrated against Lee. Given his naturally aggressive temperament as a field commander, it is unlikely Lee would have simply retreated south of the Potomac without seeking a decisive engagement—with or without Stuart. The only real question is where that fight would have occurred.

Once Lee committed his army to fighting in Pennsylvania, the issue boils down to whether Stuart’s presence on the battlefield would have made a difference. Of course, this line of inquiry is speculative at best because Stuart was not present on July 1 or for much of July 2. We can examine how Lee fought the battle with the cavalry that was available, however, and in doing so find it difficult to see how the presence or absence of the brigades that rode with Stuart would have made any difference at all in the outcome of the fighting once Lee committed his army at Gettysburg. Let’s examine why.

As already pointed out, Jenkins’s troopers operated with General Ewell’s Second Corps since the beginning of the movement toward Pennsylvania. They screened Ewell’s advance up the Cumberland Valley and performed that role competently. They may well have fired the opening shots of the battle of Gettysburg on the morning of July 1. On July 2, they were supposed to be screening Ewell’s left flank. Jenkins received orders to ride to the extreme left flank and relieve the infantry brigades of Brig. Gens. William “Extra Billy” Smith and John B. Gordon. Jenkins, however, was badly wounded by an artillery shell fragment while standing on Blocher’s (Barlow’s) Knoll, leaving Col. Milton J. Ferguson to assume command. For reasons that remain unclear, the horsemen never arrived to relieve the waiting infantry. Their failure in that task left two brigades of veteran infantry to perform the traditional role of cavalry—screening the army’s flanks. The failure of Jenkins’s Brigade to reach its assigned position also forced Brig. Gen. James Walker’s Stone wall Brigade to perform picket duty on the Confederate far left flank on Brinkerhoff’s Ridge near Culp’s Hill.

When Union cavalry under command of Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg attacked Walker’s infantry on Brinkerhoff’s Ridge, the Confederate foot soldiers were pinned down and unable to participate in the assaults against Culp’s Hill on the evening of July 2.60 In addition, the presence of active and diligent Federal cavalry on the Southern army’s left flank prevented “Extra Billy” Smith’s Brigade from taking part in Jubal Early’s dusk attack against East Cemetery Hill that same evening. Both assaults came within a whisker of success. Al though we will never know, the presence of these veteran Confederate infantry brigades might have tipped the balance in one or perhaps both of these actions. Therefore, the only tangible effect of Stuart’s absence from the battle field on the second day was that two critical brigades of Second Corps infantry were kept out of the fighting on the Confederate left that evening. Rather in explicably, Lee did not employ any of his available cavalry to scout those positions or the Federal left flank prior to James Longstreet’s after noon assault that same day. Lee had available horse men on July 1 and 2 but did not use them to scout the enemy army. Nothing in the historical record suggests he would have acted differently if Stuart’s three brigades had been present.

Many Confederate officers share the blame for the defeat at Gettysburg. As the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee bears the primary responsibility for the loss. It was Lee who ordered Stuart’s expedition in the first place. Lee did not oversee the issuance of clear and unambiguous orders that would have made speculation or interpretation by Stuart unnecessary. Had Lee written unequivocal orders, the dispute that has raged over their meaning (or whether Stuart violated them) for more than a century would not have erupted. Lee must also shoulder the primary fault for not using his available cavalry to screen his movements once he received word from Longstreet’s spy that the Federal army was marching north after him. The army commander also failed to use the horsemen riding with the army on the morning of July 1 to scout the ground ahead while Heth’s Division tramped blindly toward Gettysburg.

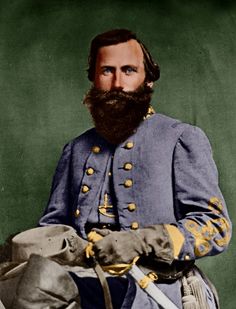

Although we believe many of the accusations leveled against Jeb Stuart have been either grossly exaggerated or factually wrong, the cavalier nevertheless bears some of the blame for the way events transpired and for the pair of tactical misjudgments he made early in the ride. Stuart, by his very nature, took liberties with the vague and ambiguous orders presented to him. He interpreted them in the fashion most favorable to his desire to lead an expedition into the Union rear. He could have selected a different lineup of brigades to accompany him, leaving Lee and the main army with more tested and reliable cavalry and commanders. He should have taken the Hopewell Gap route. Had he done so, he would have missed running into Hancock’s Corps altogether. He also could have pressed on instead of wasting ten precious hours waiting for Mosby at Buckland Mills. These two delays set the schedule for his march irretrievably behind. Stuart could have ignored the temptation to capture the wagon train, though as we have shown, its presence almost certainly helped him rather than hindered his expedition as so many writers have claimed. That same train could easily have been abandoned along the way once the need for speed became critical and negated any benefits the wagons may have provided his column. Because establishing contact with Ewell in Pennsylvania was one of Stuart’s primary objectives, he could have made more exhaustive attempts to find the Second Corps, or some other portion of the Army of Northern Virginia once his initial efforts to locate Ewell failed. However, as we have already demonstrated, there were valid reasons why Stuart followed the course he did.

We believe Beverly Robertson deserves a large share of the blame for failing to communicate to Longstreet or Lee the critical intelligence that Hooker’s army had crossed north of the Potomac between June 25 and June 27. The cavalry leader compounded his omission by violating Stuart’s direct order to follow the army immediately if the enemy moved north. Instead, Robertson waited two full days before advancing his cavalry command. His inactivity beginning on June 25 resembled his inactivity at Brandy Station on June 9. His late June sluggishness, however, left Lee’s army without its eyes and ears, even though Stuart made careful dispositions to make certain Robertson had full and complete (and easy to follow) orders. Had Robertson performed as ordered, Lee would have had plenty of cavalry available to perform the usual role he expected of his mounted arm. Instead, Robertson demonstrated his penchant for idleness, which in turn left Lee without the cavalry screen Stuart had carefully planned for him to have. Robertson’s lack of diligence deprived Lee of the benefit of both his own small brigade and the larger, more reliable brigade of Grumble Jones until the third day of July. These two brigades could have led the Army of Northern Virginia’s advance toward Gettysburg if Robertson had obeyed his orders and marched immediately when he learned the Army of the Potomac was in full pursuit of the Confederates. Perhaps John S. Mosby summed it up best when he stated, “General Stuart had passed around Hooker’s army, while General Robertson had passed around General Lee’s.”

Jubal Early also must bear some of the responsibility for the way events played out. Early clearly heard the guns booming at Hanover on June 30, yet did absolutely nothing to discover who was doing the shooting and why. Even a cursory investigation would have revealed to Early that Stuart’s command was only a handful of miles away. The reverse is also true, for a courier from Early would have informed Stuart that one of Ewell’s divisions was close at hand. Had Early taken simple, prudent steps that should have been second nature to someone with his experience and command responsibilities, he could have brought Stuart’s three brigades with him and the entire command would have reached Gettysburg on July 1—in time to participate in the critical fighting that day. Jubal Early, one of Stuart’s most vociferous critics, played a tragically significant role in triggering the chain of events that resulted in Stuart’s absence from Gettysburg until late in the day on July 2.

The Confederate War Department must be held accountable for its failure to ensure that Stuart’s critical intelligence dispatch of June 27 reached Robert E. Lee. This was the dispatch reporting that Hooker’s army had abandoned its camps at Fairfax Court House and was already across the Potomac in pursuit of the Army of Northern Virginia. Stuart knew that this information was so essential he sent it to Lee through Ashby’s Gap by courier, and a second copy to Richmond. When this critical intelligence arrived, the War Department should have taken steps to verify Lee had received the report. There is no evidence anyone in Richmond made any such attempt.

John Singleton Mosby, Stuart’s most vocal defender, is not immune from criticism for the role he played in the drama. Mosby scouted the route for the ride, and Stuart relied heavily upon the work of his favorite and most dependable scout. However, Mosby does not appear to have been particularly aggressive or diligent in his efforts to link up with Stuart, and never reconnected with Stuart’s command once the ride was under way. Further, Frank Stringfellow, another of Stuart’s favorite scouts, had been captured, which in turn left the Southern cavaliers without accurate intelligence and without their usual complement of diligent scouts to lead their advance. Instead of providing Stuart with accurate intelligence, Mosby and his men made their way to Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, on July 1, nearly sixty miles from Gettysburg, and were disappointed to find that Lee’s army had already departed. Mosby and his rangers returned to Virginia with only one herd of rustled cattle to show for their efforts. Had Mosby linked up with Stuart, his scouting and intelligence might have made it possible for Stuart to connect with either Early or Ewell quickly and in a more effective fashion. It is unlikely Mosby died unaware of the fact that he failed his patron, although he never alluded to it. Thus, his own foibles may explain the ferocity of Mosby’s defense of Stuart in the years following the end of the war.

The plucky Federal cavalry deserves a significant portion of the credit for the delays that befell Stuart’s expedition. The brave, desperate, and hopeless charge of the 11th New York Cavalry at Fairfax Court House hindered Stuart for half a day. “So, as the old saying is, ‘A little always helps, ’ and to Major Remington and his gallant little band of Scott’s 900 belongs the honor of causing the delay,” noted an Empire State horseman.

Likewise, the desperately heroic but hopeless charge of the 1st Delaware Cavalry at Westminster cost Stuart yet another half-day of riding. “Several of the officers and many of the Delaware cavalrymen claim that Stuart lost at Westminster or near it from ten to twelve hours, or to be more precise from five or six o’clock when they halted that afternoon, till four or five o’clock the next morning when they resumed the march,” observed General Wilson some years after the war. “Of course this was in the night and half of it at least was necessary for rest and sleep for both men and horses, though if they had pushed on till even nine or ten o’clock, fifteen to twenty miles more might have been easily covered before they went into bivouac.” Stuart, concluded Wilson, “could easily have reached Hanover less than thirty miles to the northward, before the Federal cavalry could have barred the road to the west from that point. This accomplished he could have passed on through Hunterstown, to a junction with Lee in a single day’s march instead of taking three days, and thus giving effective support to Lee.”

Finally, Judson Kilpatrick’s division cost Stuart a full day at Hanover, both by engaging him in battle and by forcing Stuart to take an unplanned, longer route that prevented him from linking up with Early’s Division before the Virginian headed for Gettysburg. The feisty Federal cavalry cost Stuart two full days of riding. But for those two days, Stuart would have linked up with Early at York, and his entire command would have reached Gettysburg no later than the morning of July 1. Perhaps the largest portion of the credit, or blame as it were, for Stuart’s untimely arrival at Gettysburg falls on the Union horse soldiers who blocked his way.

If Stuart disappointed anyone at Gettysburg, he more than redeemed himself during the retreat to Virginia. His performance during those difficult days, as well as that of his vaunted cavaliers, to whom the previous few weeks must have seemed a lifetime, was nothing short of magnificent. Stuart’s handling of General Lee’s mounted arm was a major reason the Army of Northern Virginia was even able to safely cross the Potomac River.

No single person or condition can or should be made to shoulder the blame for the crippling Southern loss at Gettysburg. Rather, a combination of circumstances led to the Confederate disaster. We believe the Army of Northern Virginia would have lost the battle of Gettysburg whether Jeb Stuart and his cavalry were present earlier or not. Their absence simply provides more fodder for the endless debates that continue to swirl nearly a century and a half after he finally rode up and reported his presence to Robert E. Lee.

There was plenty of blame to go around.