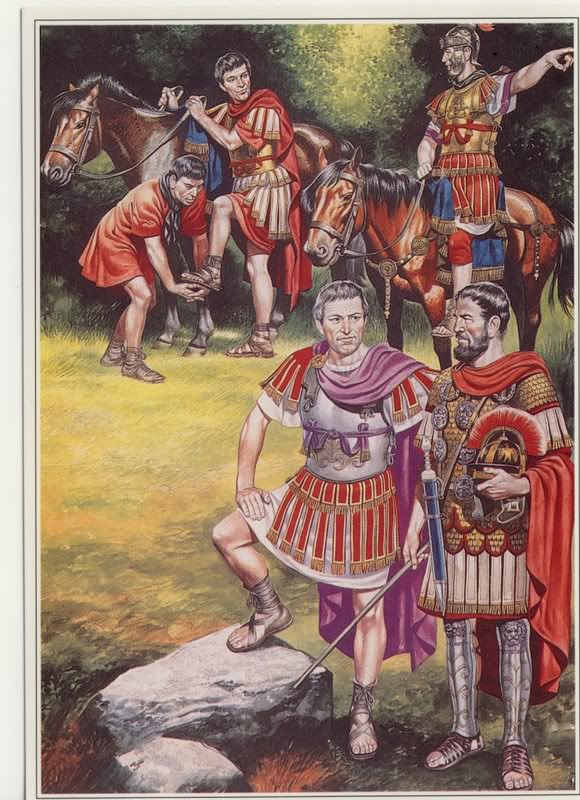

The two officers in the background are tribunes; that on the right the artist rendered as being a tribunus laticlavius. The two in the foreground are the Legate, and the primus pilus. Contrary to HBO, the thinking amongst most historians is that term means something like “first pillar,” not “first spear.” This has to do with a lengthy discussion of the derivation of the term “Hastati” (literally “spearmen”) for the guys in the front ranks of Republican legions vs. Carthage, men throwing the proverbial Roman “pilum,” and the guys behind them, especially the “Triarii,” who WERE “spearmen,” not having such a title instead.

In brief, the earliest known use of the word hasta is by Ennius (d. 169BC), and he was speaking of a throwing not thrusting weapon. Therefore the hastati carried hasta velitares, while the rear ranks carried thrusting spears, hasta longae. It is thought that “pilani” means, in this context, “pillar” or “column” as the triari were also called pilani, meaning they marched at the rear of the column… The PP was the senior centurion of the legion, and his position had derived from being the senior leader of the senior-most troops of the old republican legion. The most successful of these would aspire (and achieve) the coveted post which was the de facto if not de jure second in command of the legion, the praefectus castrorum, or “camp prefect.” As the title suggests, they had by then achieved through graft & corruption, or hard work (or both!), the necessary property qualification to be elevated into the ranks of the equestrian order (if they had not started out as such, as some centurions did).

The emergence of large, complex armies brought into existence the specialized military staffs required to make them work. The invention of the military staff may be compared in importance with the rise of the general administrative mechanisms of the state that appeared at the same time. Egypt, for example, in 3400 b. c. e. was able to organize the human and material resources to construct and maintain a 700-mile-long irrigation system along the entire length of the Nile River within Egyptian borders. Around 2500 b. c. e. the Sumerians constructed a 270-mile-long wall across southern Iraq to reduce the raids of desert bedouins-“those that did not know grain.” We are so accustomed to various forms of social organization and bureaucracy in the modern age that we are prone to forget how important a social invention administrative mechanisms were. Without them it would have been impossible for states of the ancient period to evolve the high levels of social and economic complexity that they did, and it would have been impossible to produce the large and complex armies that these administrative mechanisms made possible. The great public works projects of the ancient world, the pyramids of Egypt, the irrigation systems of Sumer and Assyria, the great walls and roads of China, and the extensive fortifications of the Roman East and India were inherently dependent on sophisticated organizational institutions and practices, which were then applied to military use.

Sumer and Egypt

We know nothing about the military staff organization of ancient Sumer, except that the king was aided by professional staff officers to supply, house, and feed the army on a regular basis. The first identifiable military staffs emerged in Egypt during the period of the Old Kingdom (2686-2160 b. c. e.). The organizational structure of these staff s is unknown, but an analysis of titles provides evidence of a sophisticated staff organization. The principle of organization was function, and there are titles for quartermaster, various officer ranks, types of commanders, and specialist sections dealing with desert warfare and garrisons. A much clearer staff structure is evident during the Middle Kingdom (2040-1786 b. c. e.), when titles for general officers in charge of logistics, recruits, frontier fortresses, and shock troops are found. The command structure of the army is fully articulated in terms of titles by this time. Titles for military police, police patrols, and military judges are evident. For the first time, there is evidence of a military intelligence service, reflected in the title “master of the secrets of the king in the army.” The regular presence of scribes suggests that much of the administrative routine may have been committed to permanent record. By 1500 b. c. e. the Egyptian armies of the New Kingdom possessed special field intelligence units, translation sections, and the first use of the commander’s conference for staff planning on the battlefield.

Assyria

Our knowledge of military staff s in Assyria is limited largely to the description of the special staff of horse logistics officers who recruited, trained, and supplied the army with 3,000 horses a month. 6 During the imperial period Assyria was a military state, and it is likely that almost all aspects of life relevant to the military establishment were controlled by military staff officers, including the secret police, the civil bureaucracy, the intelligence services, logistics, and even the training of scribes to keep accounts and records. Given the high degree of social organization and integration generally characteristic of Assyria during this time, while we have only limited evidence of military staff organization, it is a safe conclusion that it existed and was organizationally sophisticated in most respects.

India

It was during the Mahabharata War (1000-900 b. c. e.) that something approaching a modern military staff structure appeared in India. Indian military staff s provided for military training of soldiers (dhanurveda) , logistics, military intelligence, fortifications, and direction over an army with four combat arms-chariots, cavalry, elephants, and infantry. Several centuries later, during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya (321-297 b. c. e.), Indian military staff s became larger and capable of directing more complex armies. The first Indian text on politico-military organization, the Arthasastra, was written at this time by Kautilya, Chandragupta’s Brahmin advisor. The Arthasastra is a combination of Machiavelli’s The Prince and Plato’s Republic and describes how to organize a state and an army and make both work efficiently. It provides us with a good deal of our knowledge of the political and military organization of the Mauryan imperial state.

The Hittites, the Mitanni, and the Israelites

We know almost nothing about the military staff s of the Hittites and Mitanni since both were feudal societies whose armies comprised noble warrior retinues called to the service of the king. In this sense they were probably much like the later armies of medieval Europe: whatever staff s existed were personal retainers of the king with no functional authority beyond that of the king’s retinue. The Israelite army under David and Solomon was very well organized and staffed with professional officers and administrative personnel, the last drawn heavily from the Canaanite population because of their previous experience and technical expertise. The Israelites often lacked technical expertise and hired mercenaries and other technical personnel to administer to the army and the state. When Solomon wanted to construct the Temple in Jerusalem, he contracted the work out to king Hiram of Sidon, who provided the materials, workers, and design of the Temple itself, a classic example of a Canaanite temple.

China

By the fourth century b. c. e. Chinese military staff s had grown large and complex in response to the need to direct and supply very large armies, often much larger than any seen in the West during the same period. The Confucian ideal of merit-based bureaucracies had already taken root in China, and while generals and higher nobility were still appointed by the emperor, many of the middle ranks on Chinese military staff s were selected for expertise and competence. An interesting innovation found on Chinese military staff s of this period was the Philosopher of War, the most famous of which was Master Sun of the state of Wu (Wu Sun Tzu), known to history as Sun Tzu (544-496 b. c. e .). Sun Tzu’s treatise, The Art of War, was but one of dozens written by him and other intellectual condottieri who traveled from court to court, offering their advice on war. One of the most famous of these advisors was Sun Bin (380-326 b. c. e.), who wrote Theories on the Art of War.

It was during this period that the first written treatises on tactics and strategy appeared in the West. There are extant cuneiform manuals for military doctors in Assyria that imply that the Assyrians may have also written and used military textbooks to train their officers. Xenophon’s classic works on military affairs, the Anabasis and the Cyropedia, appeared at about this time as well.

Greece and Macedonia

The armies of the Homeric age, being clan warrior retinues, had neither need nor ability to develop military staffs. The same may be said for the barbarian armies- Germans, Goths, Gauls, and so on-that fought the Romans. Tribal social orders lacked clear organizational definition and did not develop the functionally lateral and hierarchical structure required by modern administrative organizations. The citizen armies of Classical Greece were part-time affairs, and there does not appear to have been any permanent staff organization, except for Sparta, itself a military society. The armies of Philip of Macedon and Alexander possessed primitive staff s that did not reach the level of sophistication of earlier armies in the Near East. Both these armies reveal special staff sections for logistics, artillery, intelligence, medical support, and, interestingly, military history. But the structures of both armies were essentially extensions of the personalities of their commanders and did not survive long enough to acquire any institutional foundations of their own.

Rome

The height of military staff development in the ancient world was achieved by the Romans. So effective was the Roman military staff system that more than any other army of the time, it could still serve as the model for modern armies. Each Roman senior officer had a small administrative staff responsible for paperwork. The Roman army, like modern armies, generated enormous amounts of permanent fi les. Each soldier had an administrative file that contained his full history, awards, physical examinations, training reports, leave status, retirement bank account records, and pay records. Legion and army level staff records show sections dealing with intelligence, supply, medical care, pay, engineers, artillery, sieges, training, and veterinary affairs. There was almost nothing in the organization or function of the Roman military staff that would not be instantly recognizable to a modern staff officer.

The degree of organization and sophistication of the military staff s of the armies of the Late Iron Age was not achieved again until the armies of the American Civil War. Even the armies of Napoleon, as sophisticated as they were thought to have been at the time, did not equal the organizational skill of the Assyrian and Roman military staff s. In terms of operational proficiency, no military staff attained the level of the Roman army staff until the German General Staff in 1820. Like the military staff s before them, the most important officers of the German General Staff were logistics officers and engineers. In the conduct of war on a large scale, whether in ancient or modern times, some things remain unchanged.