Through the sea breeze a mechanical bugle blared and the pilot looked up startled, a rice ball halfway to his mouth. Like angry ants, men poured from everywhere over the flight deck and ran toward waiting aircraft or anti-aircraft guns. Air attack . . . that was what the bugle was playing. Air attack. Jumping to his feet, Kaname Harada stared up and saw nothing. Then he squinted past the bow and saw little dark flecks appear against the lighter horizon band.

“Torpedo planes!” someone yelled over the noise. “Torpedo attack!”

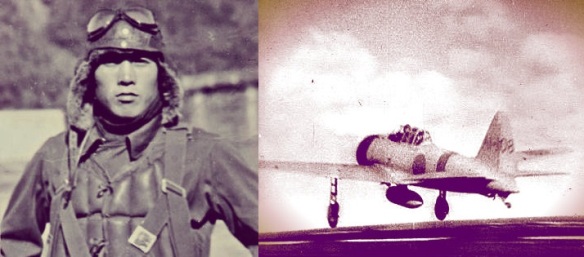

Tossing his teacup overboard, the pilot sprinted to his waiting Reisen, clambered up the wing and plopped into the cockpit. The ground crew already had the engine started and, ignoring the seat straps, he waved everyone back and held the brakes as the chocks were yanked out. Peering forward over the nose, Harada pushed the throttle up, and the fighter surged forward. His eyes were locked forward as his right hand checked the flaps down and switched on his guns.

Coming off the deck, the plane crabbed into the wind, and he held his takeoff pitch long enough to clear the carrier’s bow, then retracted the gear. As the Zero sank toward the sea he felt the propeller really bite into the air, and the fighter slowly rose. Slapping up the flaps, he leveled off for a few seconds to gain more airspeed. Glancing toward the attackers, he was shocked to see how close they were. Escort ships were firing now, and he could see black and white puffs exploding over the Americans. Beginning a wide turn, Harada waited until his wingmen were loosely joined, then he began to climb. Eyes narrowed, he realized he wouldn’t have to go too high—the Yankees were skimming the wave tops.

Hold it . . . hold it . . . He bunted slightly and began a gentle turn, gauging the intercept geometry from long experience. He could plainly see them now. They were the newer American torpedo bombers, big and ugly, like a bumblebee, with blue paint and bright white stars. The Avenger, made by Grumman, with a three-man crew.

Now . . .

Yanking back on the stick, Hamada flipped the nimble little fighter over and sliced down toward the lumbering planes. His two wingmen repositioned and floated into single file behind him. Leaving the throttle up, he lightly played the stick and rudder to swoop in from above. The Avenger had an enclosed ball turret, and as it started to swivel Harada opened fire with a three-second burst. His two cowling-mounted machine guns instantly spewed out a stream of fifty 7.7 mm shells, and the wings shuddered from the recoil of the bigger 20 mm cannons. Pieces flew off the other plane, but the American had banked up and his tail gunner was firing.

Yanking the stick back into his lap, Harada grunted and barrel-rolled the fighter up and over the torpedo bombers. Inverted, staring down at the blue water, he saw his second wingman firing and made a snap decision. Cutting in front of his third wingman, Genzo Nagazawa, Harada snap-rolled upright behind another Avenger. The other Zero immediately pulled straight up to avoid a collision, and as he did the American tail gunner fired a long, lethal burst into the fighter’s belly. Horrified, Harada saw his wingman’s plane burst into flames and smash into the sea.

Enraged, he screamed, pulled his nose to bear, and fired at point-blank range into the Avenger. The gunner’s turret disappeared in a cloud of shredded metal, glass, and smoke. The big plane instantly nosed over and hit the waves, throwing up a tremendous fan-shaped spray of water. Blinking rapidly, Harada rolled up and over again, looking down as the rest of the Americans vanished in similar flaming splashes.

It was June 4, 1942, just past 7 a.m. on a clear, sunny morning. Admiral Yamamoto, commander of the Combined Fleet, was under tremendous pressure. The Doolittle raid had graphically demonstrated the home islands’ vulnerability to air attack, and the Battle of the Coral Sea had shaken the Imperial Navy’s cult of invincibility. Yamamoto also knew he was running out of time to achieve victory before America overwhelmed Japan. His plan was twofold. First was to take Midway Island as the key to an outer range of defense that would prevent another attack on Japan. Second, to complete the mission started at Pearl Harbor by luring the U.S. Navy into a final great sea battle, where it would be crushed. With no navy to protect the West Coast, Washington would be compelled to negotiate.

Yamamoto’s complex plan involved three main prongs. First, an attack on the Aleutian Islands was intended to divert American attention and resources. Second, his main carrier strike group would hit Midway Island, destroying any chance of land-based U.S. air attacks against his fleet. The island would then be invaded and taken with its airfield intact for use by Japanese aircraft. By this time, Yamamoto calculated, the Americans would’ve sent their navy out to fight, and his Combined Fleet could trap and annihilate them.

There were several problems with this. Foremost was the broken Japanese JN-25 military code, which enabled Nimitz’s intelligence section to read anywhere from 25 to 75 percent of any given message. They’d also figured a way to nail down Midway as the target by simply referencing it in a clear message, which the Japanese then repeated in their code. Another problem was the Aleutian feint. It was so obviously a diversion that no one fell for it, least of all Nimitz, and the fact that it tied up Japanese Fifth Fleet resources (including the carriers Ryujo and Junyo) may well have turned the tide of the battle.

Last was the Japanese underestimation of American forces and, perhaps most damning, of the Americans themselves. Pearl Harbor had convinced many of the Imperial Navy’s superiority, and the lessons from Wake Island and Coral Sea hadn’t been fully digested yet. They knew that the Saratoga was in California being repaired but also believed the Yorktown had been sunk in the Coral Sea. Limping back to Pearl Harbor, however, Nimitz put 3,000 workers onboard for seventy-two hours, and the big carrier was back at sea. In the meantime, Admiral Nagumo and the First Mobile Force sailed from Hiroshima Bay on May 26, 1942. The Japanese Fifth Fleet, called Mobile Force 2, had also steamed from the home islands heading northeast toward the Aleutians. As far as Yamamoto knew, only the Enterprise and Hornet were available and his intelligence placed them far down in the South Pacific.

Which they were not.

On the same day both carriers had returned to Pearl Harbor, followed by the damaged Yorktown. At noon on May 27 the Enterprise and Hornet, with fifty-four fighters, seventy dive-bombers, and twenty-nine torpedo planes, left Oahu. Commanded by Rear Adm. Ray Spruance, Task Force 16 was escorted by six cruisers and eleven destroyers. Midway was also reinforced by four USAAF B-26 bombers and eight additional Catalinas. By 1200 on May 30, Task Force 17 had sortied from Pearl Harbor. Escorted two cruisers and five destroyers, Yorktown was carrying twenty-seven fighters, thirty-seven dive-bombers, and fifteen torpedo bombers. By June 1 nine more B-17s from the 26th Bombardment Squadron had arrived, bringing the total to sixteen heavy bombers. Also, a third U.S. task force built around the Saratoga had sailed from San Diego heading west.

As the sun set during the afternoon of June 2, Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown rendezvoused 350 miles northeast of Midway Island. The Japanese carriers of Mobile Force 1 had turned southeast and were about 700 miles when darkness fell. The invasion fleet was also 700 miles west and closing. Twelve American submarines were deployed in an early-warning screen along the northwestern approaches to Midway, and the Catalinas were still flying their patrols.

The island’s airborne defenses now included twenty-one Marine fighters (Buffalo and Wildcats) and thirty-six dive-bombers (Dauntless and Vindicators). Ground forces included two companies of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion, among whose officers was Maj. James Roosevelt, eldest son of the president of the United States.* The USAAF had deployed twenty-five bombers (B-17s and B-26s), and six new Grumman Avengers from VT-8 off the USS Hornet flew in on June 1. There were more than thirty long-range Catalinas; enormous planes with a wingspan over 100 feet, the PBYs were also used for interdiction and night attack. They could carry bombs, torpedoes, and four machine guns over their 2,500-mile range.

It was the Catalinas from VP-44 that discovered the Japanese on the morning of June 3, 1942. At 8:43 a.m. Ens. James Lyle discovered the Japanese minesweeping force about 600 miles southwest of Midway. Forty minutes later Ens. Jack Reid radioed his famous “Main body!” sighting followed up with a later report of eleven ships 700 miles west of the island, heading east. The pilot was convinced he’d found the strike force, but Nimitz was not; in fact, it was the invasion force. Still, nine B-17s from Midway launched at noon, and at 4:40 p.m. they attacked the Japanese Second Fleet Transport Group. Though no hits were scored, they did shake the Japanese up. If Midway was the point of an inverted triangle, Nagumo’s carriers were at the top left corner, about 500 miles to the northwest of the island. Due east some 400 miles, on the top right corner of the triangle were the American carriers.

First blood was drawn early in the morning of June 4 when a flight of Catalinas hit the oiler Akebono Maru with a Mk 13 aerial torpedo. At 4:30 a.m., with the element of surprise lost, Admiral Nagumo’s first strike against Midway came off the decks of Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu, and Soryu. Four squadrons of bombers with fighter escorts, the 108-plane package was picked up on radar at 5:35. By 6 a.m. everything on Midway that could fly was airborne—the bombers heading away to safety and the Marines from VMF-221 (Fighting Falcons) turning in to attack.

If the Grumman Wildcats were outclassed by the Japanese fighter, then the Brewster Buffalo was hopelessly overmatched. The Zero was at least 1,000 pounds lighter and could outclimb either American fighter by over 1,000 feet per minute. Though the Wildcat and Zero both spit out about 15 pounds of shells per three-second burst, they were outnumbered about five to one and quickly overwhelmed. Still, the Marines shot down four bombers and three fighters and put the attackers on the defensive as they approached Midway. Anti-aircraft fire took out another thirty or so aircraft and damaged most of the rest, so it was no wonder that the mission commander, Lt. Joichi Tomonaga, immediately called for a second strike. At about 7:15 a.m. Nagumo ordered his reserve squadrons armed with contact fragmentation bombs for a final mission to neutralize the island’s defenses.

As this was happening the USAAF B-26s and VT-8 Avenger detachment found the Japanese carriers. It was five of these six planes, led by Lt. Langdon K. Fieberling, that Harada and his combat air patrol of Zeros destroyed. Two of the four B-26 bombers were also shot down. Forty-five minutes later, Vindicator and Dauntless dive-bombers from VMSB-241 began their glide attacks from 8,000 feet and were cut to pieces by the Zeros. Nine of the twenty-seven didn’t return. Shortly after 8:00 a.m. fifteen B-17s arrived overhead at 20,000 feet and added their bomb loads to the confusion.

The continued attacks by American shore-based aircraft had prevented Nagumo from launching the second strike. By this time his first strike force had arrived back at the fleet for refueling and rearming, and he chose to recover the first group before attacking Midway again. A cruiser scout plane had reported enemy ships, but it wasn’t until 8:40 that an American carrier was confirmed. Once again the rearming was changed back to torpedoes and the hangar decks of all four carriers were chaotic as crews frantically worked. Stacks of bombs were everywhere, with high octane fuel hoses snaking between torpedoes and boxes of ammunition.

Unbeknownst to the Japanese, Enterprise and Hornet had launched their own attack at 7:02. Based on the timing for the Midway assault, Spruance’s chief of air staff, Capt. Miles Browning, calculated that an American strike launched now would catch the Imperial Navy in the midst of recovery and refueling—and it happened exactly that way.

The Hornet’s strike group had arrived at the estimated target point and found empty sea. Figuring that Nagumo had headed to Midway, they turned southeast and flew toward the island—all except VT-8. Lt. Cmdr. John Waldron guessed that the Japanese might be lurking beneath a low cloud layer to the north, and that’s where he found them. At 9:40, running low on fuel and without fighter escort, he attacked, followed by VT-6 off the Enterprise and VT-3 from the Yorktown. Thirty-five of forty-one torpedo planes were shot down by Zeros and anti-aircraft artillery with no hits on the ships.

But while the Japanese were taking evasive action, no launch was possible, so the flight decks were clogged with fully fueled, heavily armed aircraft. Most important, all fifty Zero fighters were down at low altitude chasing the surviving Americans. Kaname Harada later recalled, “The American aviators were exceptionally courageous. I was impressed at how bravely they pushed home their attacks.”

Nagumo was vainly trying to reorganize, regroup, and launch the next strike when his luck finally ran out. Dive-bombers from the Enterprise had trailed the destroyer Arashi back to Mobile Force 1 and found four Japanese flattops ponderously turning into the wind. As fate would have it, Lt. Cmdr. Max Leslie arrived with seventeen more dive-bombers from the Yorktown.

At 10:22 Lt. Cmdr. Wade McClusky split his thirty-seven dive-bombers into two groups, rolling in from 14,000 feet on the Kaga and Akagi. Yorktown’s VB-3 attacked the Soryu. Like lethal silver water droplets glinting in the sun, all fifty-four aircraft screamed down toward the Japanese. Harada and the other Zero pilots struggled to climb and engage, but they couldn’t stop this attack.

At least one bomb went through Akagi’s flight deck to detonate on the packed hangar deck below. Fuel and ammunition exploded, roasting flight crews in their planes and gutting the ship. Kaga went down three hours later, and Soryu would be torpedoed by a U.S. submarine and sink at sunset. The Japanese were shocked and shattered, while the exuberant Americans continued hunting for the last enemy carrier.

But the Imperial Navy still had a few teeth yet and immediately launched Hiryu’s remaining aircraft. Following behind VB-3’s returning strike force, they appeared on Yorktown’s radar at 1:30 p.m. Eighteen dive-bombers were intercepted by Wildcats from Fighting Three (VF-3), which splashed ten of them, and two more were shot down by anti-aircraft fire. However, six got through and three scored hits on the carrier, one of them disabling eight of her nine boilers. Superb damage control had her steaming again within ninety minutes, and by 4 p.m. she could make 20 knots. At the same time, radar detected a second wave of Japanese planes inbound from the west. Four airborne Wildcats immediately committed out to intercept, while those on deck, some with only 20 gallons of fuel, also took off.

The protective combat air patrol (CAP) got six of the inbound Kate torpedo bombers, but at least four survived to drop their fish. Two missed, but two more hit the port side, eventually causing a 30-degree list. Though the ship was abandoned, Yorktown’s aircraft were recovered on the Enterprise. Ten of these dive-bombers, along with a full strike package from Enterprise, set off to find the last remaining Japanese carrier.

Kaname Harada had landed his fighter aboard the Hiryu after his own carrier was hit. The plane was so full of holes that a maintenance officer ordered it pushed over the side. He was wondering what to do when a spare Zero was brought up, and he hopped in. Getting airborne at 5 p.m., he’d just glanced back when a wave of hot air hit him, bouncing the lightweight plane sideways. The entire flight deck disappeared beneath a rolling wall of fire. Smoke poured up everywhere, and he whipped his head back around, staring upward. Dive-bombers were dropping like stones, little black bombs detaching as the aircraft pulled out with vapor streaming from the wings. It was a full package from the Enterprise plus ten from the Yorktown.

Harada fought back until he was out of ammunition and out of time—the sun was setting and he had no place to land. Locking the canopy open, he dropped flaps, pulled the power, and pancaked into the sea behind a destroyer. Even as it circled back to him, B-17s showed up overhead and dropped their bombs in Midway’s final attack of the day. The destroyer fled and after floating all night, Harada was picked up the next morning by the Makigumo. In a strange twist of fate, the pilot who was first off the decks for the Pearl Harbor attack was the last one off at Midway. Harada was also rescued by the same destroyer that would scuttle the last Japanese carrier afloat—Hiryu.

Still refusing to sink, Yorktown remained afloat all night, and a second salvage operation got under way on June 5. By 3:30 p.m. that day, it actually appeared the ship might be saved. But then four torpedo wakes were spotted. Two of them struck, and by early morning on June 7, the battered carrier finally rolled over and sank.

The Imperial Navy could not cover an invasion without aircraft carriers, so Admiral Yamamoto ordered a general withdrawal to the west. Spruance and Fletcher were later criticized for not pursuing the Japanese, but this is an unfounded judgment. They had no way of knowing if an invasion would occur, or even if something other than Midway might still be a target, so they remained where they could react if necessary. There was also a very real chance of running into Yamamoto’s main battle fleet, and that would certainly have been disastrous for the few heavy American warships left.

The loss of four fleet carriers was a tremendous blow, as were the 3,000 Japanese lives lost. More than 240 aircraft went down, with nearly all their trained and experienced flight crews. It has also been estimated that 40 percent of the Imperial Navy’s mechanics, armorers, and specialists were also lost in the battle. Though it would not stop the Japanese advance, Midway did cost them their ability to conduct unrestricted offensives. This means they lost the momentum that had carried them thus far, and they would never really regain it. Over the next two years the Japanese would produce just six fleet carriers.

The 307 American sailors, crews, and pilots lost were a bad blow to a sorely pressed navy. Yorktown was a heavy loss, but from 1942 to 1945 the Americans would launch twenty-six Essex-class carriers, 45,000-ton warships carrying 2,600 men that each supported a ninety-plane air group. Nine Independence-class carriers and more than a hundred light and escort carriers would also roll down the slipways into salt water. As Yamamoto had foreseen, time was running out for the Japanese. The giant was awake, angry, and out for blood.

After the Battle of Britain, Pearl Harbor, and the Pacific battles of Coral Sea and Midway, airpower no longer had any detractors. The startling results from those key conflicts demonstrated the influence of tactical aircraft, and the men who flew them, far beyond all expectations. They were the weapons, with potential and effects previously only imagined by a few visionaries. Conventional ground forces and naval vessels that had defined warfare for six hundred years stared up at the fight and watched, basically spectators, as a new era emerged.