The ‘Star Attack’ carried out to perfection by 26th Destroyer Flotilla. Haguro was hit by torpedoes from all points of the compass. She was doomed long before the 61-minute action began by her inexplicable failure to sight her foes until within 6 miles. Her Type 22 radar had a 212-mile range.

Victory in Europe, signifying the end of World War II against Germany, was barely two days old when the British East Indies Fleet was summoned to action on 10 May 1945. No sooner had most of the fleet come to its buoys in Trincomalee harbor, Ceylon, on the 9th, wearied after the seaborne landings to capture Rangoon, than signals ordered the ships to raise steam for leaving port at 0600 next day.

Vice Admiral Sir Arthur J. Power’s East Indies Fleet included two battleships, more than a dozen escort aircraft carriers, a dozen cruisers, about 24 destroyers, and 70 frigates, minesweepers and escort vessels, with a score of submarines. This impressive fleet had been built up since April 1942 when Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s five Japanese fleet carriers, of Pearl Harbor fame, had stormed into the Indian Ocean. Their aircraft had dispersed Admiral Sir James F. Somerville’s old Eastern Fleet battleships, raided Colombo and Trincomalee with Stuka-like fury and sank two heavy cruisers and the light aircraft-carrier Hermes in displays of incredibly accurate bombing, before withdrawing after four destructive days.

Now, three years later, as Japan withdrew her forces behind an ever-shortening defense perimeter, among her far-flung outposts were the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. It was activity in the neighborhood of these islands that alerted the British fleet base at Trincomalee.

Few Japanese ships remained in the Indian Ocean but on 10 May Allied Intelligence reported that the 8in-gun, 13,380-ton heavy cruiser Ashigara and the small destroyer Kamikaze were due to sail from Singapore. Their objective was the relief of the Andaman and Nicobar garrisons. Although broadly correct, Allied Intelligence did not know that the Japanese intention was to evacuate these islands under the code name Operation Sho. The Andaman group consisted of the veteran Haguro, sister ship of Ashigara, and Kamikaze, who rather invited her name by being an old and ill-armed destroyer. The Nicobar group comprised the auxiliary supply vessel Kuroshiyo Maru No. 2 and the 420-ton, 16-knot submarine chaser No. 57.

When news of this operation was received in Trincomalee, Vice Admiral Harold T. C. Walker, second-in-command to Adm. Power, took command of every available ship in the anchorage under the title Force 61 and set sail early on the 10th. Queen Elizabeth, the Royal Navy’s oldest capital ship and first in action 30 years before, wore Walker’s flag. The French battleship Richelieu, kept from German clutches since her completion in 1940, powered through the Indian Ocean. Four US-built escort aircraft-carriers of 11,420 tons and 17 knots, Hunter, Shah, Khedive and Emperor, were the ugly ducklings of Force 61. The carriers’ flagship was the modern light cruiser Royalist streaming the broad pennant of Commodore Geoffrey N. Oliver. From 5th Cruiser Squadron came Rear-Admiral W. R. Patterson’s flagship, Cumberland, the heavy, three-funnelled cruiser whose eight 8in guns and 9,750 tons dwarfed the 3,787-ton Tromp (5 x 5.9in), sole surviving Dutch cruiser from the 1942 Java Sea battles. Eight modern British destroyers completed Force 61, a total of 17 ships, shaping a course almost due east towards the Ten Degree Channel between the Andamans and the Nicobars. The hunt for Haguro was on.

But the first British warship to establish contact with her was the small submarine Subtle, commanded by Lieutenant B. J. B. Andrew, DSC. Subtle, with her sister-ship of 8th Submarine Flotilla, Statesman, was on patrol in the Malacca Straits. At 1640 on 10 May Andrew sighted Haguro, not long out of Singapore, escorted by a destroyer and two sub-chasers. By 1704 he had closed the range to only 1,200 yards and was on the point of ordering ‘Fire!’ when Haguro made a sudden alteration of course away. Andrew viewed the stern of the cruiser with dismay, broke off the attack and ordered a dive to 90ft—only to hit the ill-charted bottom at 35ft.

Later that evening Subtle’s sighting report was received by Force 61 crossing the Bay of Bengal. Haguro’s position, course of NW and speed of 17 knots were plotted and it was expected that interception would be made on 12 May. But on the 11th events changed.

Adm. Walker ordered Richelieu, Cumberland and 26th Destroyer Flotilla to increase speed and alter course to be in a position in the Six Degree Channel between the Nicobars and Sumatra Island at dawn on the 12th. This force, named Group 3, would be well positioned to intercept Haguro should she abandon her mission and seek to return to Singapore.

During 11 May Force 61 was sighted by a Japanese aircraft and so altered to a more southerly course. The sighting was relayed to Haguro and she promptly altered course 180° back towards the Malacca Straits. Haguro and Kamikaze did, in fact, reach the Six Degree Channel at dawn on the 12th as expected, but Group 3 missed them.

Then the heavy cruiser was again sighted by the persistent Lt. Andrew in Subtle at 0640. She was steaming at 25 knots on a zig-zag track 20° either side of a mean course of 135°. Above her flew three ‘Jake’ Aichi El 3A1 twin-float sea-planes. Despite these difficulties and the flat calm sea which made periscope sighting easy for the cruiser, Andrew got to within 2,500 yards and emptied his six 21 in torpedo tubes. Her lookouts alert, Haguro turned away to comb the torpedo tracks, all of which passed by harmlessly.

The 44 submariners then endured a three-hour depth charge attack from the cruiser’s escorts which caused considerable damage including the wrecking of Subtle’s W/T gear.

Haguro’s violent alteration of course took her into Statesman’s sector, but her captain, Lieutenant R. G. P. Bulkeley, was unable to get in an attack because of the zig-zagging. However, he was able to get away a sighting report of the cruiser steering due south at 18 knots. Force 61 was disappointed for it confirmed that Haguro had eluded the trap set for her.

Adm. Walker decided to stand off to southward with Force 61, hoping to avoid detection by air and to encourage Haguro to head north again allowing another attempt at interception. Walker ordered reinforcements and two more fleet tankers from Trincomalee. On 13 May Force 62 set sail (the cruiser Nigeria and 11th Destroyer Flotilla; Roebuck, Racehorse and Redoubt). Rocket, their flotilla-mate, escorting a south-bound troopship, was ordered to detach herself and rendezvous with Force 61 on the 14th. The operation was developing like the 1941 Bismarck pursuit, with the Royal Navy again deploying ships as pieces in a massive game of oceanic chess.

During 13 May Force 61’s destroyers refueled from the escort carriers. One ship of 26th Destroyer Flotilla, Virago, collided gently with the carrier Emperor. Force 61 headed eastward to begin closing the trap, reaching the Six Degree Channel at 0400 on the 14th. Force 61 remained in this area for 1 ½ hours then, in .the absence of any further news, headed for a rendezvous with the tanker Echodale of Force 70, 200 miles SW of the NW tip of Sumatra.

But unknown to Adm. Walker events were developing almost exactly as his staff had predicted. Haguro and Kamikaze had left the One Fathom Bank in the Malacca Strait for another dash to the Andamans. Meanwhile, the Nicobar relief force, Kuroshiyo Maru No. 2, and her sub-chaser escort, had reached Nancowry Island in the Nicobars, hurriedly embarked 450 troops and departed on the afternoon of the 14th for Penang. Within hours of her departure Kuroshiyo Maru was sighted by a patrolling Liberator bomber of No. 222 Group RAF, from Ceylon. This report was quickly transmitted to Force 61. Walker implemented Operation Mitre, the code name given to the air-and-sea sweep throughout the Andaman Sea to find and destroy any Japanese shipping.

Walker detached Cumberland with 21st Aircraft Carrier Squadron’s four escort carriers and the flagship Royalist, plus 26th Destroyer Flotilla (Captain Manley L. Power, DSO, in Saumarez) to lead the sweep ahead of the main force. They proceeded through the night at high speed. Unknown to all, the trap was closing, not on the Kuroshiyo Maru No. 2, but on Haguro.

During the darkness of the middle watch of 15 May events took a dramatic turn. At 0237 Capt. Power was ordered to lead his five destroyers to find the auxiliary vessel spotted by the Liberator. At 0325 Rear-Adm. Patterson in Cumberland took command of the operation: Richelieu was ordered to join Patterson. Adm. Walker in Queen Elizabeth with her escorting destroyers and carriers kept to the westward in support.

To those in 26th Destroyer Flotilla now powering ENE at 27 knots through a placid sea, the rising sun silhouetted the hills of Sumatra fine on the starboard bow. All destroyers’ ships’ companies were manning action stations at dawn—and would do so for the rest of the day.

Soon after 0700 the carrier Emperor flew off a flight of four Avenger bomber/reconnaissance aircraft of No. 851 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm. The pilots had been briefed carefully to sight, shadow and report. But the first pilot to make a sighting disregarded his instructions. He despatched a sighting report of Kuroshiyo at 1029, attacked her ineffectually and was shot down. The survival dinghy eventually drifted ashore in Burma and the three-man crew became POWs for four months. Yet, curiously, Sub-Lieutenant J. Burns, RNVR, had contributed to Haguro’s final destruction.

Capt. Power was still leading Saumarez and his four V-class destroyers at 27 knots when he received a signal at 1041, from C-in-C East Indies:

IMMEDIATE. CANCEL MITRE. REPEAT CANCEL MITRE.

The recall was judicious. Power’s flotilla was now way ahead of Group 3’s heavy ships, within easy range of Japanese Sumatran airfields and the operation was fast needlessly hazarding five valuable destroyers.

But Power was dismayed at the order. In the Operations Room aboard Saumarez he discussed the situation with his officers. Power invoked the discretionary Section 1, Clause 1 of the Fighting Instructions: ‘Very good reason must exist before breaking off contact with the enemy. In the event of an order from a senior officer, the possibility must be considered that he may not be in possession of the facts.’ Power reasoned that his namesake in Trincomalee, the C-in-C, was unaware of the Avenger’s sighting report and of the fact that worthwhile enemy targets lay ahead. But as flotilla commander (Captain (D)), Power also compromised. He signalled Adm. Patterson aboard Cumberland for confirmation of the cancellation, reduced speed to 15 knots, but steadfastly maintained course ENE. It was a crucial act of calculated disobedience, a Nelsonian ‘blind eye’ to be vindicated by success.

For while Power was engrossed in his dilemma, four more Avengers had been launched from Emperor. One, piloted by Lieutenant Commander M. T. Fuller RNVR, CO of 851 Sqdn. radioed : ‘One cruiser, one destroyer sighted. Course 140°. Speed 10 knots.’ The position placed the ships only 15 miles SE of the abortive air attack on Kuroshiyo.

The two ships—a misidentified Haguro and Kamikaze—were only 130 miles ahead. Their second attempt to relieve the Andamans had been cut short and they were now on the first leg of the run south to Singapore through the Malacca Straits.

‘Going like a full-back!’

Saumarez received Lt. Cdr. Fuller’s signal soon after noon on the 15th. Power ordered 27 knots and minutes later—at 1221—his course was ESE to round the northern tip of Sumatra, going, as the Secretary to Captain (D) Lieutenant Denis Calnan later wrote, ‘like a rugby full-back for the corner flag’. The heavy guns of Richelieu and Cumberland were 100 miles astern. The destroyers were on their own.

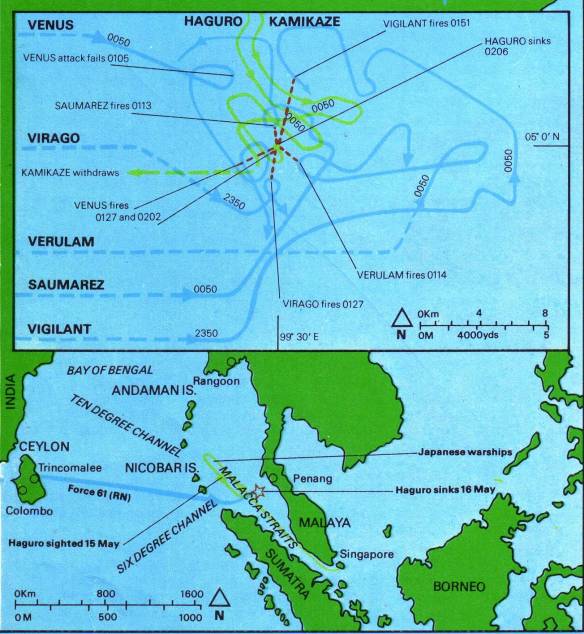

Capt. Power’s intention was to head for the Malayan coast south of Penang and then to sweep back westwards across the 130-mile-wide Malacca Straits thus depriving Haguro of silhouetted targets against the setting sun. If contact were made in daylight, the destroyers would attempt to maintain extreme range and that was 18 miles for the cruiser’s 8in guns. Haguro must be driven or enticed to destruction under Richelieu’s 15in guns. If the encounter was at night, the flotilla would launch a torpedo ‘Star Attack’, radar-directed and simultaneous from five points.

As the destroyers sped east and south through the blistering heat of a tropic afternoon, Adm. Patterson signalled Power that action should not be broken off as ordered by the C-in-C: ‘You should sink enemy ships before returning.’ It was some assignment!

At 1355 the carrier Shah flew off three Avengers which found and bombed Haguro at 1530, claiming one hit on the forecastle and a near-miss to port by the bridge, despite a fierce barrage from the cruiser’s 52 25mm AA guns.

At 1900, with Sumatra only 20 miles to starboard and beginning to be lost to sight in the dusk and deteriorating weather, Power ordered the destroyers into line abreast, each ship four miles apart. Saumarez (flotilla leader), in the center, had Virago and Venus to port and Verulam and Vigilant to starboard. Course was 110°. Darkness brought heavy, squally rain and flashes of lightning. Haguro and Kamikaze were 75 miles NE, course 140° and speed 20 knots, but Power was ignorant of this.

It was not until as late as 2245 that doubts were partly dispelled when Ordinary Seaman N. T. Poole, radar operator aboard Venus on the port wing of the flotilla, reported an echo bearing 045° at the unbelievable range of 68,000 yards (38.6 miles). These exceptional ranges were always treated with caution until confirmed. Venus‘ captain Commander H. G. de Chair ordered the echo plotted. Nineteen minutes later it faded, but, at 2310, it re-appeared range 53,000 yards (30 miles) bearing 039°. Twelve minutes later de Chair was satisfied that the contact was a genuine ship echo and he signalled Saumarez: ‘Contact bearing 040° 23 miles (40,480 yards), course 135°, speed 25 knots.’

Capt. Power questioned the report, but de Chair now had the confidence to signal ‘Contact now bearing 034°, range 20 miles, course 130°, speed unchanged at 25 knots.’ The plot soon suggested that Haguro was altering course to starboard, nearer to due south, and at 2338 Venus came round to 170° to keep fine on the cruiser’s starboard bow.

At 2345, one hour after the first echo, Power ordered his flotilla to prepare for a Star Attack and signalled Adm. Patterson of his intention. All now depended upon the tenuous radar link between Venus and Haguro. The Japanese cruiser was still unaware of the mounting danger about her. Then at 2348 the echo faded. Power ordered de Chair to close the target and shadow.

Like a bull led by the nose

At 0003 Saumarez picked up an echo 14 miles (24,640 yards) ahead, which when plotted corresponded with Venus‘ tracking. Power then employed a shrewd tactic. The flotilla’s course was altered to the south and its speed from 20 knots to 12 knots so that it was running slowly ahead of Haguro allowing her—at 20 knots—to run on into the trap. The inestimable advantage of their advanced Type 293 radar allowed the British destroyers to dominate this phase of the battle with almost casual ease. Haguro was being led by the nose like a bull.

Fifteen minutes after midnight, when the destroyers were positioned in the shape of a huge crescent from NW through S to E with Haguro only 13 miles from the center, the flotilla turned about and increased speed to 20 knots. The trap was being sprung. All destroyers now had Haguro on their screens and they took up their attack sectors smoothly. At 0042 Power signalled that Saumarez would attack with torpedoes at 0100 on the 16th. The other destroyers would synchronize their attacks. Incredibly, Haguro still failed to open fire on targets which by now must have appeared on her radar screens. The silence lent an air of unreality to the scene. Then Haguro, apparently bewildered, blinked a recognition signal almost at the same time as the radar echoes on the British screens separated to indicate Haguro with Kamikaze close astern.

At 0054, six miles from her hunters, Haguro, now thoroughly alive to the danger, turned 180° to the north and assumed full speed, in excess of 30 knots, with Kamikaze hurrying to catch up. This astute move led the Japanese ships directly out of the crescent-shaped trap. Saumarez had been close to an ideal bow-angle torpedo shot at the cruiser but now she had an impossible stern shot. Power saved his torpedoes, and tried to concentrate on the confused and high-spirited action which now developed with seven warships maneuvering at full speed firing all guns and launching torpedoes.

At 0105 Venus, parallel to Haguro as she raced past the most NW ship in Power’s net, found herself in a perfect attacking position. Cdr. de Chair’s binoculars were filled with the two funnels of the cruiser: the range was closing rapidly to 300 yards with Haguro 450 on the bow. But the Torpedo Control Officer aboard Venus had made the wrong angle settings on her eight tubes, the Opportunity was lost and Venus heeled hard over to port to clear the target area but still maintain the encirclement. Haguro, thinking Venus had launched torpedoes, frantically altered course away to comb the tracks. In so doing she turned south and deeper into the trap.

Saumarez.and Verulam were now well positioned to make their attacks. Haguro appeared fine off Saumarez‘s port bow, range 6,000 yards (3.4 miles), each ship closing at 30 knots. At the same time Kamikaze appeared off the starboard bow, crossing from starboard to port, only 3,000 yards away and on a collision course. Gunfire shattered the night, the flashes competing with the lightning in illuminating the elderly Japanese destroyer’s bow wave.

Saumarez‘s second salvo from her two forward, radar-controlled 4.7in guns struck Kamikaze and 40mm Bofors shells from the British ship’s aft twin-mounting ripped the whole 320ft length of the Japanese destroyer as Saumarez heeled violently to starboard. Power had ordered full helm to pass under the stern of Kamikaze. It was a near miss. By now Haguro’s first thunderous broadside of ten 8in and four 5in guns drowned all speech and sense. The explosions erupted tremendous waterspouts alongside, swamping the flotilla leader’s upper decks. Haguro could be seen clearly three miles away in the light of both sides’ star-shells, her high sides glistening wet and her guns depressed to their lowest angle.

At 0111, just as she was about to fire torpedoes, Saumarez was hit. The top of her funnel disappeared over the side and a 5in shell penetrated No. 1 Boiler Room, severed a steam main and lodged inside the boiler. Five men were scalded but, like the 8in hits, the shell failed to explode at such close range and was later thrown overboard by the Engineer Officer with a Petty Officer’s help. As the destroyer’s speed fell away with her radar and gyrocompass out of action, Power grimly attempted a torpedo attack to port with the cruiser only 2,000 yards abeam. On the bridge Power aimed by eye as his officer in the torpedo aiming-station vanished in the deluge from a near-miss. Eight torpedoes sped away at 0113 with Saumarez still heeling over to open the range and to clear the area out of the barrage of shells falling about her. For three frantic minutes the ship was under emergency steering from the aft station by the Captain’s Secretary before the engine-room staff connected up the surviving boiler to drive both her propeller-shafts.

Verulam, spared the ordeal of her Captain (D), also fired eight torpedoes one minute after Saumarez. Three gold colored flashes at 0115 thrown twice as high as the cruiser’s bridge heralded three hits—shared between Saumarez and Verulam. As the damaged Saumarez limped northward from the immediate battle area a violent explosion created confusion. Power thought it was Kamikaze blowing up. Virago and Vigilant thought it was Saumarez, but it was probably two torpedoes colliding. The Chief Engine-Room Artificer in Venus clearly heard the whirring of two torpedoes passing close alongside.

By 0120 (the battle was still only 15 minutes old) all ships were engaged in gunfire attacks. The slowed-down Haguro twisted and turned in desperation, but wherever she turned she encountered a destroyer. At 0125 Cdr. de Chair had conned Venus into an attacking position from the west and fired six torpedoes, one of which was clearly seen to strike home. At 0127 Lieutenant Commander A. J. R. White in Virago fired his complement of eight torpedoes at the cruiser which by now was mortally injured. Two of these torpedoes hit and Haguro began to settle in the sea. Her guns still continued to fire but she was losing way and her main deck became awash.

Vigilant‘s defective radar had lost track of the battle, so the destroyer had yet to carry out a torpedo attack and did not do so until 0151, when she scored one probable hit on the burning cruiser from the eight torpedoes she launched. Venus was ordered by Power to administer the coup de grace at 0202 with her two remaining torpedoes. At 500 yards range both struck home and Haguro ended her career at 0206, after a one-hour action, in a position 5°0? N, 99°30? E, about 55 miles WSW of Penang.

Saumarez, laying off five miles to the NW to lick her wounds, signalled ‘Pick up survivors. Stay no more than ten minutes.’ In the event, because of a false enemy aircraft sighting and the imminence of daylight, no survivors were rescued by the British destroyers. Kamikaze, only slightly damaged by Saumarez, returned to the scene an hour later and rescued nearly 400 men of Haguro’s 773-strong complement.

At 0210 the four V-class destroyers formed up on Captain (D) and steamed westward at 25 knots towards Richelieu and Cumberland, now less than 50 miles away. The 26th Destroyer Flotilla had fought the last major surface gun and torpedo action of World War II and carried out one of the finest sinkings of a heavy ship by destroyers alone. Lord Louis Mountbatten, himself a distinguished destroyer captain, gave the action his seal of approval when he described it in his Report to the Combined Chiefs of Staff as ‘an outstanding example of a night attack by destroyers.’