For all his troubles, Secretary Welles enjoyed major advantages over Secretary Mallory: the North had a functioning naval bureaucracy, a growing number of ships with an officer corps and a pool of mariners adequate to man them, and a large maritime and industrial base upon which to draw. In his efforts to circumvent Welles’s blockade, Mallory had to start from scratch in every area, from administrative organization to biscuit bakeries and shipyards. Beyond the 247 U. S. Navy officers who “went south,” he had a handful of seized revenue cutters and the resources of the partially destroyed Gosport (Norfolk, Virginia) Navy Yard. This profound maritime weakness made a symmetrical force-on-force strategy impractical. Lacking the resources to challenge the Union with wooden steamships, Mallory decided to place his faith in technology. Invulnerability, he wrote, could make up for unequal numbers, and he approved plans to convert wooden ships into ironclad vessels. Confederate workmen began the first conversions in mid-1861.

The Confederacy’s number one project, at least in terms of causing anxiety to Union officials, was the conversion of the scuttled steam frigate USS Merrimack into the ironclad CSS Virginia. Workmen at the Gosport Navy Yard started the project in July 1861, and officials in Washington received regular reports of their progress from spies and newspapers. The Federals were especially concerned about the Virginia project because besides breaking the blockade of Norfolk, the ironclad might bombard Fort Monroe or steam up the Potomac River to threaten the Union capital.

Naval arm of the Confederate States of America in 1861–1865; established at Montgomery, Alabama, on 21 February 1861. Former U.S. senator from Florida Stephen Russell Mallory was the Confederacy’s first and only secretary of the navy, from April 1861. Initially, the navy was administered by Mallory and a few clerks.

There was no organizational structure or administration already in place at the time of the navy’s establishment. The lack of money, industry, and infrastructure necessary for building warships and other instruments of war greatly complicated matters. Another problem was a shortage of trained officers and men to man the warships. Mallory’s challenges were considerable. Unlike his counterpart, Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, who inherited a fully functional naval organization, Mallory had to build a navy from scratch and struggle to sustain it through four arduous years of war.

The Confederacy had a vast coastline to protect against a vastly larger Union navy. Mallory sought to defend this coast as well as waterways, including the Mississippi River. Offensively, his strategy centered on issuing letters of marque to owners of private vessels (privateers) to take Federal ships and carry out commerce raiding against Northern commerce. This, he anticipated, would drive up insurance rates and bring the war home to the North. Finally, and most important to Mallory, he sought to challenge the Union blockade through ironclad warships.

Lacking manufacturing facilities at home, Mallory sent agents to Europe to acquire ships. Among these agents were Commander James H. North and Captain James D. Bulloch. Bulloch procured the commerce raiders Alabama, Florida, and Shenandoah. He also contracted with John Laird & Son for two powerful rams; but when the war turned against the South, British officials seized these ships as being in violation of international law.

In its organization and regulations, the Confederate navy closely followed the U.S. Navy. By the Act of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States of America (CSA), the Navy Department consisted of a Marine Corps, Office of Ordnance and Hydrography, Office of Orders and Details, Office of Provisions and Clothing, and Office of Medicine and Surgery, all presided over by the secretary of the navy. Each bureau was headed by a captain, the marines by a commander. As the need arose, other more specialized agencies came into being, such as the Office of Special Services and the Torpedo Bureau. Among personnel slots were a chief naval engineer and a chief naval constructor.

Since it dealt with personnel matters for officers and enlisted men and issued orders and regulations emanating from the secretary, the Office of Orders and Details was the most influential of the bureaux. Initially, Captain Franklin Buchanan, who resigned from the U.S. Navy, headed this bureau.

Since there was no chief of staff in the Confederate navy, each office acted independently without centralized planning or coordination. As a result, naval policies, rules, and regulations were sometimes vague and slowly implemented.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis displayed little interest in naval matters. While he gave Mallory full reign in his area of responsibility, Davis also channeled scarce resources to the army and disregarded Mallory’s pleas for additional ships, guns, manpower, and resources.

The Confederate navy needed able-bodied and knowledgeable officers and sailors to man its ships. As with the U.S. Navy, politics and influence found their way into personnel decisions. Almost half of the officers of the U.S. Navy were from the South, and many accepted the call to serve in the Confederate navy at the same rank. The problem was to find positions for these officers. The glut of officers forced many to accept commissions in the army. Two men reached the rank of admiral in the Confederate navy: Franklin Buchanan and Raphael Semmes. Securing seamen was a major problem. They were too few in number and many preferred army service. Not only was there a lack of qualified sailors, but shortages of skilled shipyard workers, engineers, machinists, and others held up the construction of warships.

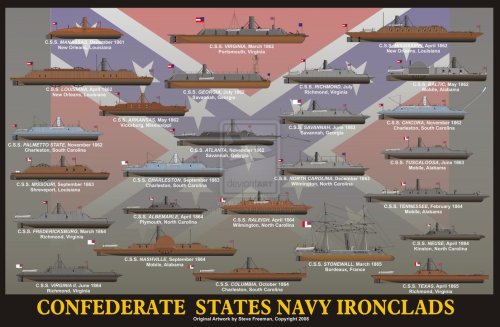

Despite the scant resources provided it by the government, the Confederate navy helped bring about a technological revolution. This included the construction of ironclad rams, forcing a Union response. Lieutenant John M. Brooke’s rifled guns were among the best of the war on either side, while the H. L. Hunley was the first submarine to sink an enemy warship when it attacked the USS Housatonic in Charleston harbor on 17 February 1864. The Confederates also made extensive use of “torpedoes” (underwater mines).

Stephen Russell Mallory, (c. 1813–1873)

Secretary of the navy of the Confederate States of America. Born in Trinidad in 1813 Stephen Russell Mallory moved to Key West, Florida, at an early age. His father died when he was nine. Mallory studied three years at a Moravian school for boys in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, and then assisted his mother in running a boarding house. In 1833 he was appointed customs inspector at Key West, where he read for the law with a local judge. Admitted to the bar before 1840, he specialized in maritime cases. During the 1836–1840 Second Seminole War he was a volunteer aboard a gunboat, and in 1845 he became collector of customs at Key West.

In 1851 Mallory was elected to the U.S. Senate from Florida. He served on the Naval Affairs Committee, and on his reelection in 1857, he became its chairman. He used this position to push for naval expansion and technical innovations. He also attempted to reinstate flogging, a move favored by many professional naval officers.

Mallory resigned his Senate seat on the secession of Florida, and in February 1861 Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed him secretary of the navy. He was only one of two cabinet officers to keep his same position throughout the entire war, in part because he got along well with Davis. Mallory soon established a navy department patterned after that of the United States. Before the outbreak of the Civil War, Mallory sent naval agents to purchase supplies in the North, in Canada, and in Europe.

Mallory was a staunch advocate of commerce raiding, which he hoped would disrupt the North financially, divert Union warships from the blockade of Southern ports, and pressure an end of the war. He also dispatched naval agents to Europe to purchase cruisers and contract for the construction of others. Mallory’s other great goal was the acquisition of ironclad vessels to help break the Union blockade and even attack Northern ports. He established the Torpedo Bureau, which experimented with torpedoes (naval mines) and the means to deliver them against Union warships; and he had the good sense to recognize innovative subordinates, such as Lieutenant John Mercer Brooke.

Mallory came under increasing criticism after the loss of the Confederate ports of New Orleans, Memphis, and Norfolk and the destruction, to avoid capture, of the Virginia (ex-Merrimack). A committee of the Confederate Congress investigated him but cleared him of all charges.

Mallory resigned his post on 2 May 1865. Shortly thereafter he was arrested and imprisoned. Released in March 1866, he returned to Florida to practice law. Mallory died on 9 November 1873 at Pensacola.