In the years between the world wars, governments and military leaders theorized about the future of aerial warfare. But during this almost two-decade period, there was only one major military conflict–the Spanish Civil War. Although only a few countries officially participated, they found it invaluable preparation for World War II.

The Spanish Civil War had its beginnings in Spain’s elections of February 1936. The Republicans, consisting of the Communists, Socialists, and Basque and Catalonian separatists, won by a narrow margin. Under the leadership of Jose Calvo Sotelo, the right wing (monarchists, the military, and the Fascist Party) continued to oppose the elected government. In July, the Republicans arrested, then assassinated Sotelo, ostensibly in retaliation for the killing of a policeman by the Fascists. The right wing, now united as Nationalists, used this as their justification for launching a revolution. On July 17, 1936, General Francisco Franco and soldiers loyal to him seized a Spanish Army outpost in Morocco. In Spain, other Nationalist troops quickly seized other garrisons. A junta of generals, led by Franco, declared themselves the legal government, and the war officially began.

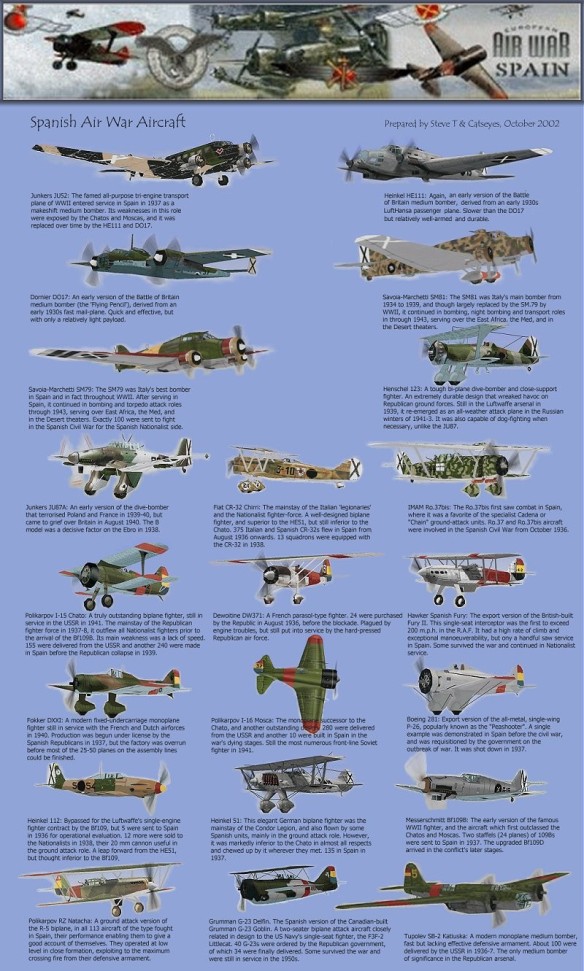

The world was forced to take sides. Many countries, including the United States and Great Britain, chose to stay neutral, believing that involvement would lead to war. However, individuals from neutral countries did volunteer with the Republican’s International Brigade, feeling the cause was worth fighting for. A group of three Americans pilots formed the Patrolla Americana, which eventually grew into a unit of 20 pilots. The Soviet Union, recognizing a potential Communist nation threatened by fascism, was quick to offer aid, including equipment, soldiers, and senior advisors. Many of their planes, including the Polikarpov I-15 and I-16, formed the backbone of the Republican Air Force. And as a gesture to protect itself from being surrounded on three sides by Fascist nations, France provided some aircraft and artillery.

Because a non-intervention agreement in 1936 forbade sympathetic nations to provide airplanes to the competing sides, it was difficult for the Republican government to develop a solid aviation program. It bought small amounts of aircraft where it could, which meant that its air force was composed of small numbers of a lot of different airplanes, from different companies and countries. The Republican government also accepted civilian aircraft, such as the Lockheed Orion, which it could then adapt to military use. There was also a Boeing P-26 that had been brought over as a demonstration model for the Spanish Air Force before the war and was “inherited” by the Republicans.

The Fascist nations found ways to avoid the rules of the non-intervention agreement. Benito Mussolini in Italy was quick to support Franco and sent Spain more than 700 airplanes and troops during the conflict. But it was Germany that was most instrumental in the war. Only days after the war erupted, Franco had sent a request for help to Adolph Hitler.

For Germany, the Spanish Civil War came at an opportune time. The nation was initiating a rearmament program, in violation of the World War I peace treaty. A war in Spain would distract the world’s governments from this transgression. Plus, Spain had raw materials that Germany could use. Hitler also liked the idea of threatening France with a Fascist government to its south. But most importantly, Spain would provide an opportunity to test equipment and train troops. Although Hitler was careful not to send enough troops to make the world perceive them as a combatant nation, 19,000 German “volunteers” gained valuable combat experience in Spain. Because the Nationalists already had strong army support, Germany sent over mostly aviators from the Luftwaffe.

The Germans were organized into the Condor Legion that was equipped with the most modern airplanes and a specially trained staff. Many of the newest airplanes were tested in real combat situations, among them the Heinkel He.111, and the Messerschmitt Bf.109. The Legion was divided into bomber, fighter, reconnaissance, seaplane, communication, medical, and anti-aircraft battalions, and also included an experimental flight group. The chief of staff was Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen, a cousin of “The Red Baron.”

The first challenge the German Condor Legion faced was the 20,000 Nationalist troops stranded at the outpost in Morocco, prevented by a Spanish Navy blockade that was loyal to the Republicans from joining the remainder of the Nationalist Army in Seville. The Condor Legion succeeded in evacuating the troops by air—something that had never been done before. On August 6, twenty Junkers Ju-52 transports arrived in Morocco. Over the next two months, the Condor Legion transported all the Nationalist troops to Seville, with the loss of only one airplane. U.S. General Hap Arnold later described the airlift as the most important air power development of the interwar period.

After the evacuation, the Condor Legion settled into other jobs. It flew harassment raids against Republican forces and supported ground forces. And it initiated both strategic and tactical bombings. While military thinkers of the time were debating the validity of aerial bombing, the German troops in Spain were obtaining practical experience.

The Condor Legion used tactical bombing after Soviet airplanes began arriving in October 1936 to strengthen the Republican side. Bombings would weaken the troops for the ground attack. In Bilbao, in the north of Spain, saturation bombing was used to shatter the Republican “Iron Belt”—a 35-kilometer (22-mile)-long line, leaving holes open for advancements; it also prevented Republican reinforcements from reaching the gaps.

But it was the strategic bombing attacks that attracted the most attention. In the beginning, methods were crude; Republican bombers were given tourist maps to help find their targets. But soon, the attacks became routine. Yet there were no riots or uprisings as theorists had anticipated. Instead, civilian resistance and resolve on both sides were strengthened. One British observer noted that the Spanish would “blacken every balcony so as to get a good view of bursting shrapnel.”

Of all the bombing raids, it was the attack on Guernica, a city in the north of Spain, which came to symbolize the horrors of aerial bombing. Guernica was the center of Basque identity and culture, boasting the parliament building and an oak tree under which Basque leaders annually swore to uphold the liberties of the people. For three hours on the afternoon of April 26, 1937, planes from the Condor Legion dropped 100,000 pounds (almost 91 million kilograms) of bombs on the city and strafed citizens in the street by machine guns. Republican sources reported 1,500 dead. The only military target in town, a bridge, remained untouched. Instead, it appeared to many, including a London Times correspondent, that “the object of the bombardment was seemingly the demoralization of the civilian population and the destruction of the cradle of the Basque race.”

Everyone was shocked by the attack, which raised ethical questions all over the world. For many years, the Nationalists denied involvement and claimed that the Basques had bombed themselves for propaganda. They did not admit their involvement until they released reports in the 1970s, after Franco’s death. The Republicans used the tragedy to gain support, displaying Pablo Picasso’s painting Guernicain the Spanish Pavilion at the 1938 Paris World’s Fair. But in the end, the greatest effect of the bombing was to make some European nations fear they might be the next Guernica and thus, they capitulated to Hitler’s demands at Munich in September 1938.

At the Nuremberg trials following World War II, Luftwaffe commandant Hermann Goering said, “Spain gave me an opportunity to try out my young air force.” The experience gained in Spain helped Germany in the early months of the war far more than the desktop theories and controlled tests of other nations. Having noted poor results from strategic bombing, Germany focused its funds elsewhere. Many planes were tested in real combat situations. And Germany also learned that even with air superiority, a bomber force still required a fighter escort.

But most instrumental were the 19,000 Luftwaffe personnel who rotated through the Condor Legion until the Republicans surrendered in January 1939, leaving the Fascists and Franco in power. Several months later, these veterans of the Spanish Civil War would be flying over Poland, Czechoslovakia, France, and the rest of Europe–an experienced, well-trained air force fighting for Hitler.

Sources and additional reading:

Boyne, Walter. The Smithsonian Book of Flight. New York: Wing Books, 1987.

Buckley, John. Air Power in the Age of Total War. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1999.

Corum, James S. The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918-1941. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 1999.

Howson, Gerald. Aircraft of the Spanish Civil War. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990.

Kennett, Lee. A History of Strategic Bombing. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1982.

Pape, Robert A. Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1996.

Ries, Karl and Ring, H. The Legion Condor: A History of the Luftwaffe in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. West Chester, Pa.: Schiffer Military History, 1992.

Robb, Theodore K. “Artists at War: Picasso’s Guernica.” MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History, Air Power Issue, 1996.

“Aircraft of the Spanish Civil War.” http://www.zi.ku.dk/personal/drnash/model/spain/SpainAir.htm

“Spanish Civil War.” Encyclopedia Britannica On-Line. http://www.britannica.com/ (A 30-day trial subscription only; full access requires payment. Encyclopedia is also available on CD.)

“Aviones de la Guerre Civil Espanola.” (this page is in Spanish but is the best single listing of airplanes and photographs on the web.) https://web.archive.org/web/20050213090600/http://usuarios.lycos.es/mrval/GCE.HTM#%5BNUEVO%5D

This website is gone but here is a listing.

A

AERO A.100/A-101/AB-101

AIRSPEED AS.6 ENVOY / AS-8 VICEROY

ARADO AR-66

ARADO AR-68

ARADO AR-95

AVIA B.534

AVIA BH-33

AVIA-51

AVRO 504

AVRO 594 AVIAN

AVRO 643 CADET

AVRO TIPO 620 /CIERVA C.19

B

BEECH MODELO 17 STAGGERWING/UC-43

BELLANCA Mod.28-90

BLACKBURN L.1 BLUEBIRD

BLERIOT-SPAD S.510

BLERIOT-SPAD S-51

BLERIOT-SPAD S-91

BLOCH M.B.210

BLOCH M.B.200

BLOCH MB-300

BOEING MODELO 247

BOEING P-26A

BREDA BA-28

BREDA BA-65

BREESE DALLAS MOD-1 RACER

BREGUET 460/462 VULTUR

BREGUET 470 FULGUR

BREGUET BR.26T

BREGUET BRE.19

BRISTOL 105 BULLDOG

BRITISH AIRCRAFT B.A. EAGLE

BÜCKER BÜ -131 JUNGMAN

BÜCKER BÜ -133 Jungmeister

C

CANTZ Z-506 AIRONE

CANTZ Z-501

CAP GP.4

CAPRONI AP-1 APIO

CAPRONI CA-310

CAPRONI CA-100

CAUDRON C-270/C-272/C-276 LUCIOLE

CAUDRON C-59

CAUDRON C.600 AIGLON

CAUDRON SERIE C-440 GOELAND

CIERVA C.30A

CONSOLIDATED MOD.17/20 FLEETSTER

COUZINET 100/101

CURTISS T-32 /BT-32

D

DE HAVILLAND D.H.60 MOTH

DE HAVILLAND D.H.89 DRAGON RAPIDE

DE HAVILLAND D.H.80A PUSS MOTH

DE HAVILLAND D.H.87A HORNET MOTH

DE HAVILLAND D.H.83 FOX MOTH

DE HAVILLAND D.H.90 DRAGONFLY

DE HAVILLAND D.H.82A TIGER MOTH

DE HAVILLAND D.H.9

DE HAVILLAND D.H.84 DRAGON

DEWOITINE D.332 /D.333

DEWOITINE D.27/D.53

DEWOITINE D-37/D-371/D-372/D-373

DEWOITINE D.500 / D.510

DORNIER DO-17

DORNIER DO-J WALL

DOUGLAS DC-2

DOUGLAS DC-1

F

FAIRCHILD KR.22

FAIRCHILD 91 / A-942

FAIREY FEROCE /FANTOME

FARMAN F.230 /F.231 / F.354

FARMAN F.400

FARMAN F.430/431/432

FARMAN F.480 ALIZE

FARMAN SERIE 190

FIAT BR-20 CICOGNA

FIAT CR-20

FIAT CR-30

FIAT CR-32

FIAT G-50

FIAT-CMASA G.8

FIESELER FI-156 STORCH

FOCKE WULF FW-56 STOSSER

FOKKER C.X

FOKKER D.XXI

FOKKER F-VII

FOKKER F-XVIII

FOKKER F-XII

FOKKER F.XX

FOKKER G.1A

FORD TRI-MOTOR

FREULLER VALLS MA

G

GENERAL AIRCRAFT ST-25 UNIVERSAL

GENERAL AVIATION G.A.43 CLARK

GONZALEZ-PAZO GP.1

GONZALEZ-PAZO GP-2

GOTHA GO-145

GOURDOU LESEURRE LGL-32

GOURDOU LESEURRE GL-633

GOURDOU-LESEURRE GL-482

GRUMMAN FF-1 / G-23

H

HANRIOT SERIES H-170/H-180/H-190

HANRIOT SERIE H-43 (H-431 – H-439)

HAWKER FURY

HAWKER OSPREY

HEINKEL HE-45

HEINKEL HE-60

HEINKEL HE-46

HEINKEL HE-59

HEINKEL HE-70 BLITZ

HEINKEL HE-50 / HE-66

HEINKEL HE-111

HEINKEL HE-115

HEINKEL HE-112

HEINKEL HE-51

HENSCHEL HS 123

HENSCHEL HS-126

HISPANO E-30

HISPANO E-34

I

IMAM ROMEO RO.41

IMAM ROMEO RO-37

J

JUNKERS F-13

JUNKERS JU-52/3m

JUNKERS JU-87 STUKA

JUNKERS JU-86

JUNKERS K-30

JUNKERS W-33 / W-34

K

KLEM L-32

KLEMM L-25

KOOLHOVEN FK.51

KOOLHOVEN FK.52

KOOLHOVEN FK-40

L

LACAB GR-8

LATECOERE 28

LETOV S-231

LIORE-ET-OLIVIER LEO-213

LOCKHEED 8 SIRIUS

LOCKHEED 9 ORION

LOCKHEED L-10 ELECTRA

LOCKHEED VEGA

LOIRE 46

M

MACCHI M-41 BIS

MACCHI M.18

MARTINSYDE F-4 BUZZARD

MESSERSCHMITT BF-108 TAIFUN

MESSERSCHMITT BF-109 /V /BCD

MESSERSCHMITT M.35

MESSERSCHMITT BF-109E

MILES M-2

MILES M-3 FALCON

MONOCOUPE 90

MORANE SAULNIER MS-140

N

NIEUPORT DELAGE NI-D 52

NORTHROP DELTA

NORTHROP GAMMA

P

PERCIVAL SERIE GULL

POLIKARPOV RZ NATACHA

POLIKARPOV R-5

POLIKARPOV I-152 / I-15Bis

POLIKARPOV I-16

POLIKARPOV I-15

POTEZ 25

POTEZ 54

POTEZ 56

POTEZ 58

PWS 10

PWS 26

R

ROMANO R-90 / R-92

ROMANO R.82

RWD 13

RWD 8

RWD 9

S

SAB-SEMA 12

SAVOIA MARCHETTI SM81 PISPITRELLO

SAVOIA MARCHETTI SM79 SPARVIERO

SAVOIA-MARCHETTI S.62

SAVOIA-MARCHETTI S.55

SEVERSKY SEV-3 / SEV-2PA

SIKORSKY S-38

SPARTAN 7-W EXECUTIVE

SPARTAN CRUISER

STINSON RELIANT

T

TUPOLEV SB-2

V

VICKERS TIPO 132 VILDEBEEST

VULTEE V-1A

Spanish Air Force –Post-Civil War

The present Spanish Air Force (Ejército del Aire, or EdA) was officially established on 7 October 1939, after the end of the Spanish Civil War. The EdA was a successor to the Nationalist and Republican Air Forces. Spanish Republican colors disappeared and the black roundel of the planes was replaced by a yellow and red roundel. However, the black and white Saint Andrew’s Cross (Spanish: Aspa de San Andrés) fin flash, the tail insignia of Franco’s air force, as well as of the Aviazione Legionaria of Fascist Italy and the Condor Legion of Nazi Germany, is still in use in the present-day Spanish Air Force.

Under the post-Civil War regional military regional structuring, all relevant air bases would be withdrawn from Catalonia. Even though formerly important air bases had been established in or around Barcelona, like the Aviación Naval, the whole northeastern area of Spain would be left with mere token presence of the Spanish Air Force, a situation that persists to this day. The Air Regions and their Command centres after the changes introduced at the beginning of the dictatorship became the following:

1st Air Region. Central.

2nd Air Region. Straits.

3rd Air Region. East.

4th Air Region. Pyrenees.

5th Air Region. Atlantic.

Balearic Islands Air Zone

Morocco Air Zone

Canary Islands and East Africa Air Zone

The Blue Squadron (Escuadrillas Azules) was an air unit that fought alongside the Axis Powers at the time of the Blue Division, Division Azul Spanish volunteer formation in World War II. The Escuadrilla azul operated with the Luftwaffe on the Eastern Front and took part in the battle of Kursk. This squadron was the “15 Spanische Staffel”/JG 27 Afrika of the VIII Fliegerkorps, Luftflotte 2.

During the first years after World War II the Spanish Air Force consisted largely of German and Italian planes and copies of them. An interesting example was the HA-1112-M1L Buchón (Pouter), this was essentially a licensed production of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 re-engined with a Rolls-Royce Merlin 500-45 for use in Spain.

In March 1946 the first Spanish military paratroop unit, the Primera Bandera de la Primera Legión de Tropas de Aviación, was established in Alcalá de Henares. It first saw action in the Ifni War during 1957 and 1958. Because of US Government objection to use airplanes manufactured in the USA in her colonial struggles after World War II, Spain used at first old German aircraft, such as the T-2 (Junkers 52, nicknamed “Pava”), the B-2I (Heinkel 111, nicknamed “Pedro”), the C-4K (Spanish version of the Bf 109, nicknamed “Buchón”), and some others. Still, Grumman Albatross seaplanes and Sikorsky H-19B helicopters were used in rescue operations. This is why still now in present times, EdA maintains a policy of having jet fighters from two different origins, one first line fighter of North American origin, and one from French-European origin( F-4C Phantom / Mirage F1, Mirage III; EF-18A / Eurofighter Typhoon).

Although in sheer numbers the EdA was impressive, at the end of World War II technically it had become more or less obsolete due to the progress in aviation technology during the war. For budget reasons Spain actually kept many of the old German aircraft operative well into the 1950s and 1960s. As an example the last Junkers Ju-52 used to operate in Escuadrón 721 training parachutists from Alcantarilla Air Base near Murcia, until well into the 1970s. The CASA 352 and the CASA 352L were developments built by CASA in the 1950s.