To the Romans, the military meant the legions, brigades of Roman citizens commanded by senior senators. They realized that these needed supplementation, but organized the cavalry and light-armed troops they employed as “auxiliaries,” or supplementary troops, in alae and cohorts commanded by prefects of equestrian origin.

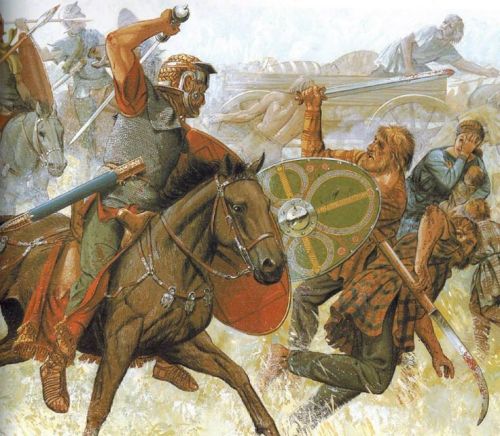

Cavalry performed such a vital role in scouting that ancient armies would have brought them along for that purpose alone, but they also had their uses on the battlefield. Horse archers did not need supports in the same way as the foot archers we have already mentioned: they could always make their escape if their tormented targets tried to charge them (indeed, the Romans themselves faced this frustration in trying to deal with desert tribesmen like those of Tacfarinas). Cavalry units were used for “shock” action as well, but it is important to stress that horses will not physically charge into formed infantry, because they perceive the unit as a solid object. Occasionally a charging horse might be killed at the last moment, and achieve what no living horse will dare, but on the whole cavalry units had to stop before steady footmen. Hence the importance of the long spear, which enabled the rider to outreach his opponent in the ensuing fencing. From the reign of Trajan on, we hear of units armed with the kontos, a heavy two-handed lance, and from the second-century onwards cataphracts and clibanarii – lancers with scale or plate armor completely covering both horse and rider – become more common. As noted, cavalry cannot ride over infantry, but it is certainly plausible that the combined noise, speed, and glittering appearance of a charge by these troops would cause their opponents to turn and run, presenting the cavalry with an opportunity for a massacre. Onasander stresses the fearsome effect that any troops could produce with ferocious shouting and dazzling weapons – “the terrible lightning flash of war” (The General 28-29) – but armored cavalry were ideally suited for this sort of psychological warfare.

After the battle, cavalry played perhaps their most decisive role: pursuit. A victor with a preponderance of cavalry would be able to pursue and slaughter the fleeing enemy (in Tacitus, Ann. 5.18, a cavalry pursuit was expected, but nightfall curtailed it; Trajan’s Column, Scene 64 shows a Dacian rearguard battling with African auxiliary horsemen, and Scenes 142-3 show Roman cavalry in pursuit). Conversely, if a defeated army had more horsemen, it might be able to mitigate the disaster somewhat by checking the victors’ pursuit.

Mons Graupius (ad 84), of which we have a relatively detailed account (Tacitus, Agr. 35-37) was unusual in one respect: the auxiliaries alone made up the first line (unusual but not unique: Cerialis adopted the same deployment in the battle just mentioned). Otherwise it exemplifies several of the features of Roman tactics which we have discussed: the holding back of a reserve, usually of cavalry, in this case four alae, “against the sudden emergencies of war” (ad subita belli); also the use of cavalry to hammer home the victory: there is no reason to suppose that before the pursuit began the Britons had lost many more men than the 360 Romans who were killed, but by the end of it, Tacitus claims, there were 10,000 British dead.

Suetonius Paulinus had used what was perhaps a more common deployment against Boudicca (ad 62): legionary troops in the center (the Fourteenth and part of the Twentieth legions), auxiliary infantry on either side of them, and on the far wings, the cavalry. 10 On this occasion, confident of victory (rather undermining Roman claims to have been seriously outnumbered) the Romans received the charge of the Britons in place, before, javelins thrown, delivering a charge of their own which swept Boudicca’s men before it. The impression which Tacitus gives is of a battle decided very swiftly, perhaps in much less than an hour, which gave way to a prolonged pursuit and massacre of the British troops and camp followers, whose escape was impeded by the carts they had parked behind their initial position. About 400 Romans were lost.

The quingenary part-mounted unit (the cohors equitata) had the infantry of a quingenary infantry cohort and 120 cavalry, whilst the milliary version had ten centuries of infantry and 240 cavalry; the cavalry were divided into turmae probably 32 strong. The alae or cavalry units contained either 16 or 24 turmae, thus containing 512 or 768 men.