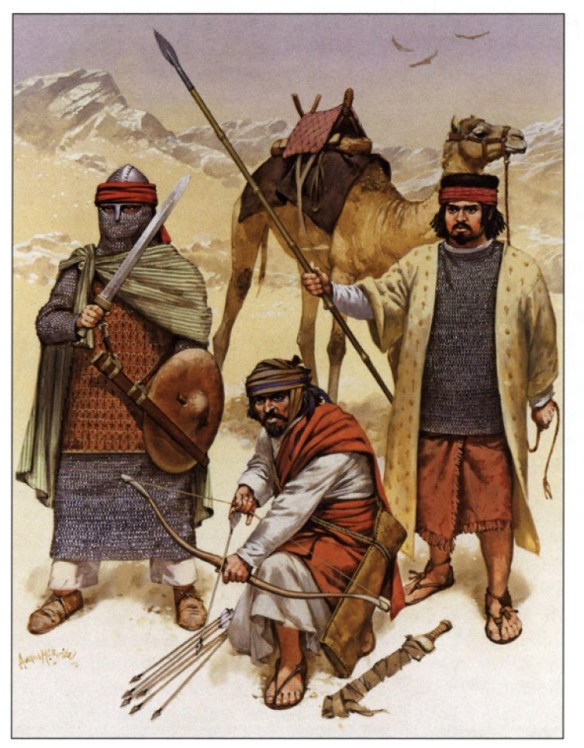

Muslim Arab warriors from the time of the Prophet Muhammad, based upon a small amount of archaeological and illustrative evidence, plus an abundance of detailed written recollections dating from only a few decades later. The military equipment ranges from armour and helmets of equal quality to those used by neighbouring Byzantine and Sassanian armies, to simple weapons including arrows tipped with stone rather than metal heads.

After returning to Roman territory in 628, Heraclius could congratulate himself on a job well done. The integrity of the Roman Empire had been restored; an ally now sat on the throne of the Sassanids, the potency of Roman arms had again been proven and, perhaps most importantly, with the imminent restoration of the True Cross and other relics, the pre-eminence of Christianity has been demonstrated. He may have expected that after almost twenty years of unbroken warfare he would be able to get some rest. However, those years of war had caused such devastation and displacement that the work of the newly styled – `Faithful in Christ Basileus’ – was far from finished. The end of the Romano-Persian War of 602-628 might have seen the restoration of a similar accord to that of Mauricius and Khusro II in the last years of the sixth century but both empires had spent a vast amount of energy and resources to return to what was essentially a status quo ante. While Heraclius’ reputation and military victories will have gone some way to restoring Roman authority over the territories recovered from Persia, there was still a lot of physical and psychological damage to deal with; damage that could not be fixed with the stroke of a pen or an agreement between allies. The infrastructures, economies and way of life in those regions directly affected by the conflict will have been greatly disrupted and the end of hostilities `did not instantly restore the old high stream of revenues to Constantinople.’

Militarily, Heraclius favoured demobilisation to relieve some of the financial pressure on the imperial treasury, especially as `it was hard to justify paying large sums for the army when no great enemy was in sight.’

There is little evidence for the size of Heraclius’ army at any stage during his reign or for the extent of these post-war demobilisations. However, it is unlikely that Heraclius reduced the numbers of what would be considered the regular army so most of his cuts would have come from discharging non-Roman contingents. Even if such a move was provable, the service of such forces was always poorly recorded compared to the regular forces so it would not provide much help for estimating the Roman army of about 630. It is suggested that the army was smaller than that of Justinian, perhaps being somewhere between 98,000 and 130,000.However, the increasing political crisis in Persia may have made Heraclius think twice about demobilisation. The threat of an enterprising Persian general or king deciding to make a grab for the prestige of an attack on Roman territory meant that the Roman emperor was obliged to maintain a sizeable force along the eastern frontier. These fears will have been somewhat allayed as Persian began to fight Persian, but the presence of Roman forces in Persian Mesopotamia when the Muslims attacked in 633 may suggest that Heraclius was still exercising caution or was even attempting to further strengthen the Roman position between the rivers.

Heraclius’ continued preoccupation with Persia and with reducing the budget may be best demonstrated in the lack of military action taken to reestablish the Roman position in the Balkans, which had been almost irrevocably smashed by the Avars and the Slavs. The extent of the campaigning that Mauricius had needed to cow the Avars in the 590s and the risk of another Phocan-like mutiny from the mass transfer of troops will have further discouraged Heraclius from redeploying to the Balkans. That Heraclius would refuse to reclaim the environs of his own capital meant that any attempts to retake control of Spain from the Visigoths or to reassert the waning imperial authority in Italy in the face of an increasingly confident Papacy and the continually unchecked Lombards would have been even further from his mind.

In the realm of religion, the military victories achieved by Heraclius offered no solution to the controversies surrounding the nature of Christ. Along with his marriage to Martina, Heraclius’ promotion of Christian worship, cults and the veneration of relics to galvanise the Empire during the war may well have exacerbated the religious disputes; disputes that were already centuries old, with no solution in sight even when Heraclius himself got directly involved. Perhaps most importantly for the future of the Empire, the losses in military and civilian manpower through combat, disease and other medical issues would have ranked in the thousands, perhaps higher, and would take years to recover. Some of these shortages could have been alleviated by the influx of refugees from Persian territory. However, they would have provided a combination of potential benefits with their `multifaceted talents and knowledge and a potential security issue being extra mouths to feed and bodies to settle or house’.6 Such a flood of people may also have played a role in encouraging Heraclius to maintain a military presence along the Romano-Persian frontier.

Despite his attempts to reduce the military budget, Heraclius seems to have immediately instituted a sizeable rebuilding programme, throwing large amounts of public funds into restoring the ruined sites around Constantinople and other large cities. In hindsight, these resources may have been better diverted elsewhere as the Empire would face continuous financial trouble throughout the remainder of the seventh century, but in the early 630s the boost to public morale will have seemed more immediately important. The marriage of the future Constantine III to Gregoria, the daughter of Nicetas, sometime before February 630 was not only a further cementing of the Heraclian dynasty but also another opportunity for morale-boosting celebration and pageantry.

The most prominent celebration of 630 was the imperial pilgrimage to see the restoration of the True Cross to Jerusalem. However, it may have had an unforeseen consequence. Heraclius’ presence in Jerusalem, along with some limited attempts perhaps to re-establish the Ghassanids buffer system, may have given rise to the Muslim belief that the Roman emperor was planning a campaign against them; a belief that may have encouraged them to take advantage of the political vacuum in northern Arabia. The termination of monetary payments to the remaining Arab clients as a cost-cutting measure seems to have `increased tensions, resentments, and violence, and disrespect for imperial authority in some areas on the margins of settled regions in Palestine and Syria’. This was demonstrated by the reported widespread raids of 632. It is not recorded who these raiders were but it is likely that they were Arabs, Muslims or otherwise.

It is not known what the Romans and Persians really knew about Muhammad’s consolidation and expansion of power in Arabia. Rumours must have perforated the frontiers to some extent but it is unlikely that local authorities will have paid all that much attention. Petty kingdoms of the Arabian sands had risen and fallen at regular intervals in the preceding centuries, and if word reached Heraclius and Shahrbaraz they will have seen this `Umma as no threat and its new Islamic `superstition’ as nothing but a passing fad.

The Romans were not only distracted from the unification of Arabia by their own internal healings but also by the catastrophic political collapse of Sassanid authority that took place in mid-630. Shahrbaraz’s removal of Ardashir III may have seemed like the advent of a new political stability based on military power and the alliance with Heraclius but it quickly descended into chaos. His military usurpation backed by the Roman emperor meant that Shahrbaraz was unpopular with much of the Sassanid hierarchy from the outset and, once he demonstrated the slightest military weakness, he was vulnerable. As it was, Shahrbaraz failed his first military test, ultimately sparking the unravelling of his regime.

The nature of this military test was not unfamiliar to the Persians. Despite the failure of the Romano-Turkic alliance to capture Tiflis in 627, the success of Heraclius’ invasion and the subsequent Persian disarray had encouraged the Turkic Khan to try again. After a two-month siege, the Turks were finally able to storm the walls of Tiflis and `a dark shadow of dread came upon the pitiful inhabitants of the city [that did not lift until] the wailing and groaning ended and no one was left alive.’ This success further emboldened the Turks to invade Armenia, perhaps in an attempt to subjugate it. Shahrbaraz, who was seemingly only just on his way to Ctesiphon from Syria, sent 10,000 men under Honah to deal with this invasion. However, by chasing after a retreating Turkic contingent, Honah and his army fell into a trap and in the subsequent slaughter the Turks `did not spare a single one of them.’ The loss of such a large number of men proved fatal to Shahrbaraz as he was assassinated barely six weeks after he had removed Ardashir.

Normally, such Persian dynastic in-fighting would not have been much cause for concern for the Roman emperor but this was an abnormal situation. Not only had Heraclius lost an ally in Shahrbaraz, he was now faced with a potential return to conflict as the Sassanid state fell into increasing political disarray. The deaths of Khusro II, Kavad II, Ardashir III and now Shahrbaraz in rapid succession, along with the circumstances, had significantly weakened Sassanid authority. The situation was exacerbated by Kavad’s `killing of almost every eligible or capable male heir in the Sasanian family’. The extent of this fratricide was not fully realised until it came to finding a suitable Sassanid candidate to replace the usurper Shahrbaraz. That the choice eventually fell on a daughter of Khusro II, Buran, demonstrates the dire state to which the Sassanid family had been reduced.

Throughout her fifteen-month reign Buran had some success in reorganising the war-torn Persian state by rebuilding infrastructure and lowering taxes, as well as maintaining good relations with Heraclius. However, she could do little about the increasing destabilisation of imperial authority. Rival claimants and increasingly powerful and disloyal generals and officials undermined any successes she achieved and when she was deposed by one such general in October 631 Sassanid central authority fell into complete chaos; so chaotic that the chronology of the early 630s is far from clear. Later historians and numismatic evidence suggest that in the year following Buran’s deposition at least seven different people claimed the Sassanid throne. Her immediate successor in Ctesiphon was Buran’s own sister, Azarmigduxt, but she too seems to have fallen foul of the military after only a few months. Across the Empire other distant Sassanid relatives and military leaders emerged as contenders, with the regnal names of Hormizd VI, Khusro III, Peroz II, Khusro IV and Khusro V all mentioned in the record. The accession of Yazdgerd III in mid-632 seemed like just another name to be added to the confusion but, through strong leadership and some good fortune, Yazdgerd would achieve some semblance of order and through the support of the military would reign for nearly two decades. Normally, such an extended reign would be beneficial to restoring a regime’s standing but, as already mentioned, these were far from normal times and Yazdgerd’s twenty years were the most turbulent in Sassanid history and would ultimately prove fatal.

While the forces available to Heraclius can be somewhat estimated, the state of the Sassanid military in the early 630s is a complete mystery. The defeats suffered during Khusro’s war with the Romans will have undermined the less than professional military structure of the Sassanid state and this will have been further destabilised by Shahrbaraz’s rebellion, Honah’s defeat by the Turks, and the civil wars. Therefore, despite the lack of information, it would not be going too far to suggest that the Persian military was not in its best shape to deal with what was about to emerge from the desert.

It is easy to criticise the post-war strategies of the Romans and Persians: Heraclius for being more concerned with the economic, infrastructural and spiritual well-being of his empire than its military strength and battle readiness; the Persians for so readily descending into resource-sapping internecine conflict. However, such criticism is heavily tainted by the benefits of hindsight and the over-expectation that the Great Powers should have been able to predict the Arabic storm that was about to erupt. After having been at war with each other for the last twenty-six years, expending vast amounts of resources in an ultimately fruitless conflict, it cannot be surprising that the Romans and Persians would become more insular in their outlook in the immediate aftermath. However, even if it is understandable, this insularity was to have far-reaching consequences for Rome, Persia and virtually the entire ancient world.