The tradition of the Republic had been that a senator should be prepared to serve the state in whatever capacity it demanded, and be proficient. A practical people, the Romans believed that the man chosen by the competent authority would be up to the task in hand. In the Republic that authority had been the electorate, under the Principate it would be the emperor. In other words there was no training for the job. Thus the man sent to command an army would have to learn the skills himself, from the leisure of reading books or the harder lesson of the battlefield.

It is interesting that handbooks on military tactics and the art of generalship continued to be written under the emperors, notably by Onasander (under Claudius), Frontinus (under Domitianus), Aelian (under Traianus), Arrian (under Hadrianus) and Polyainos (under Antonius Pius). All these authors claimed to be writing with a principal purpose, namely to elucidate military matters for the benefit of army commanders, and even the emperor himself. Thus Frontinus, in the prologue of the Strategemata, explains his intentions:

For in this way army commanders will be equipped with examples of good planning and foresight, and this will develop their own ability to think out and carry into effect similar operations. An added benefit will be the commander will not be worried about the outcome of his own stratagem when he compares it with innovations already tested in practice. Frontinus Strategemata 1 praefatio

As under the Republic, the emperors saw no need to establish a system to train future commanders. On the contrary, it was still believed that by using handbooks and taking advice, a man of average ability could direct a Roman army (Campbell 1996: 325-31).

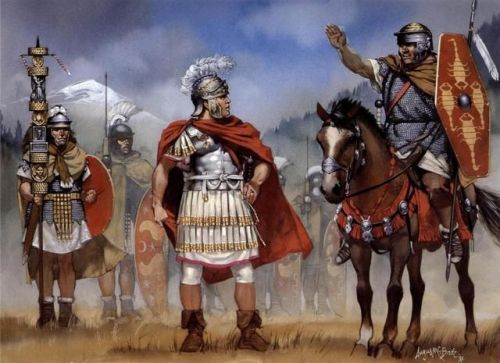

Traditionally the Romans had an organized but uncomplicated approach to tactics. The principles were: the use of cavalry for flank attacks and encirclement; the placing of a force in reserve; the deployment of a battle line that could maintain contact, readiness to counterattack, flexibility in the face of unexpected enemy manoeuvres. As the disposition of forces and the tactical placing of reserves were vital elements of generalship, the Roman commander needed to be in a position from where he could see the entire battle. The underlying rationale of this style of generalship is well expressed by Onasander when he says the general can aid his army far less by fighting than he can harm it if he should be killed, since the knowledge of a general is far more important than his physical strength’ (Strategikos 33.1). To have the greatest influence on the battle the general should stay close to, but behind his fighting line, directing and encouraging his men from this relatively safe position.

This was certainly what Antonius Primus did at Second Cremona (AD 69). In bright moonlight the Flavian commander rode around urging his men on, ‘some by taunts and appeals to their pride, many by praise and encouragement, all by hope and promises’ (Tacitus Historia 3.24.1). That other renowned Flavian general, Q. Petilius Cerialis, is depicted during the rebellion of Civilis (AD 70) doing the same thing, which occasioned no small risk (ibid. 4.77.2).

During his governorship of Cappadocia, Arrian had to repel an invasion of the Alani. Arrian wrote an account of the preparatory dispositions he made for this campaign, the Ektaxis kata Alanon. This unique work, in which the author represents himself as the famous Athenian soldier-scholar Xenophon, sets out the commands of the governor as if he were actually giving them. He had two legions, XII Fulminata and XV Apollinaris, and a number of auxilia units under his command, in all some 20,000 men. Arrian himself took charge of the dispositions and recognized the need for personal, hands-on leadership:

The commander of the entire army, Xenophon [Le. Arrian], should lead from a position well in front of the infantry standards; he should visit all the ranks and examine how they have been drawn up; he should bring order to those who are in disarray and praise those who are properly drawn up. Arrian Ektaxis 10

To carry out his orders Arrian could look to the legionary legate (one of the legati legionis seems to be absent), the military tribunes, centurions and decurions. Nonetheless, it is interesting to note that the tactics advocated by Arrian are safe and simple, competent rather than brilliant.

Of all the senior officers listed above, it was the centurions that were the key to an army’s success in battle. Centurions were a strongly conservative group who had a vital role to play in preserving the discipline and organization of the army and providing continuity of command. Yet they owed their position of command and respect to their own bravery and effectiveness in combat, and when they stood on the field of battle they were directly responsible for leading their men forwards. Thus their understanding of an intended battle plan was vital for success simply because they were the ones commanding the men on the ground.

The aquilifer played an important if comparatively minor leadership role in battle too. He was, after all, the man who served as a rallying point during the chaos of battle, and could urge hesitant soldiers forwards during a particularly dangerous moment. C. Suetonius Paulinus had formed his army up opposite Mona (Anglesey) ready to assault, but his soldiers wavered at the eerie spectacle of incanting Druids and frenzied women on the shoreline. They were spurred into action, however, when ‘onward pressed their standards’ (Tacitus Annales 14.30.2). When we consider the singular value the soldiers placed on their aquila and how its loss to the enemy would mean a permanent stain on the honour of their unit, it comes as no surprise to learn that some sacrificed themselves in its defence. At Second Cremona the aquila of VII Galbiana was only saved after’Atilius Verus’ desperate execution upon the enemy and at the cost, finally of his own life’ (Tacitus Historiae 3.22.3). L. Atilius Verus, once a centurion of V Macedonica, was primus pilus of the rookie VII Galbiana.

Closely associated with the standards was the cornicen, a junior officer who blew the cornu, a bronze tube bent into almost a full circle with a transverse bar to strengthen it. Another instrument was the tuba, a straight trumpet, played by the tubicen. Music was used for sleep, reveille and the changing of the guard (Frontinus Strategemata 1.1.9, Josephus Bellum Iudaicum 3.86), but its main function was tactical. Therefore on the battlefield itself different calls, accompanied by visual signals such as the raising of the standards, would sound the alarm or order a recall (Tacitus Annales 1.28.3, 68.3). Naturally, when the troops charged into contact and raised their war cry (clamor), the cornicines and tubicines blew their instruments so as to encourage their comrades and discourage the enemy.