The Athenian Empire, like all its predecessors, had been achieved by war, and many people could not conceive of one without the other. The problem was intensified by the character of the Athenian empire, a power based not on a great army dominating vast stretches of land but on a navy that dominated the sea. This unusual empire dazzled perceptive contemporaries. The Old Oligarch pointed out some of its special advantages:

It is possible for small subject cities on the mainland to unite and form a single army, but in a sea empire it is not possible for islanders to combine their forces, for the sea divides them, and their rulers control the sea. Even if it is possible for islanders to assemble unnoticed on one island, they will die of starvation. Of the main land cities which Athens controls, the large ones are ruled by fear, the small by sheer necessity; there is no city which does not need to import or export something, but this will not be possible unless they submit to those who control the sea.

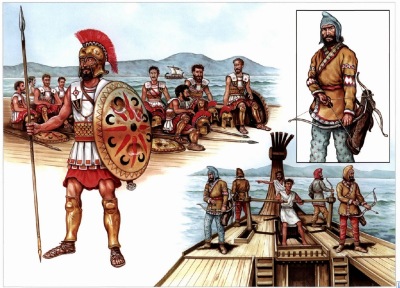

Naval powers, moreover, can make hit-and-run raids on enemy territory, doing damage without many casualties; they can travel distances impossible for armies; they can sail past hostile territory safely, while armies must fight their way through; they need not fear crop failure, for they can import what they need. In the Greek world, besides, all their enemies were vulnerable: “every mainland state has either a projecting headland or an offshore island or a narrow strait where it is possible for those who control the sea to put in and harm those who dwell there.”

Thucydides admired sea power no less and depicted its importance more profoundly. His reconstruction of early Greek history, describing the ascent of civilization, makes naval power the dynamic, vital element. First comes a navy, then suppression of piracy and safety for commerce. The resulting security permits the accumulation of wealth, which allows the emergence of walled cities. This in turn allows the acquisition of greater wealth and the growth of empire, as the weaker cities trade independence for security and prosperity. The wealth and power so obtained permit the expansion of the imperial city’s power. This paradigm perfectly describes the rise of the Athenian Empire. Yet Thucydides presents it as a natural development, inherent in the character of naval power and realized for the first time in the Athens of his day.

Pericles himself fully understood the unique character of the naval empire as the instrument of Athenian greatness, and on the eve of the great Peloponnesian War he encouraged the Athenians with an analysis of its advantages. The war would be won by reserves of money and control of the sea, where the empire gave Athens unquestioned superiority.

If they march against our land with an army, we shall sail against theirs; and the damage we do to the Peloponnesus will be something very different from their devastation of Attica. For they cannot get other land in its place without fighting, while we have plenty of land on the islands and the mainland; yes, command of the sea is a great thing.

In the second year of the war, Pericles made the point even more strongly, as he tried to restore the fighting spirit of the discouraged Athenians:

I want to explain this point to you, which I think you have never yet thought about; it is about the greatness of your empire. I have not mentioned it in my previous speeches, nor would I speak of it now, since it sounds rather like boasting, if I did not see that you are discouraged beyond reason. You think you rule only over your allies, but I assert that of the two spheres that are open to man’s use, the land and the sea, you are the absolute master of all of one, not only of as much as you now control but of as much more as you like. And there is no one who can prevent you from sailing where you like with the naval force you now have, neither the Great King, nor any nation on earth.

This unprecedented power, however, could be threatened by two weaknesses. The first resulted from an intractable geographic fact: the home of this great naval empire was a city located on the mainland and subject to attacks from land armies. Since they were not islanders, their location was a point of vulnerability, for the landed classes are reluctant to see their houses and estates destroyed.

Pericles made the same point: “Command of the sea is a great thing,” he said. “Just think; if we were islanders, who could be less exposed to conquest?” But Pericles was not one to allow problems presented by nature to stand in the way of his goals. Since the Athenians would be invulnerable as islanders, they must become islanders. Accordingly, he asked the Athenians to abandon their fields and homes in the country and move into the city. In the space between the Long Walls they could be fed and supplied from the empire, and could deny a land battle to the enemy. In a particularly stirring speech, Pericles said, “We must not grieve for our homes and land, but for human lives, for they do not make men, but men make them. And if I thought I could persuade you I would ask you to go out and lay waste to them yourselves and show the Peloponnesians that you will not yield to them because of such things.”

But not even Pericles could persuade the Athenians to do that in mid-century. The employment of such a strategy based on cold intelligence and reason, flying in the face of tradition and the normal passions of human beings, would require the kind of extraordinary leadership that only he could hope to exercise, and even in the face of a Spartan invasion in 465–446, Pericles was not able to persuade the Athenians to abandon their farms. In 431 he imposed his strategy, and held to it only with great difficulty. But by then he had become strong enough to make it the strategy of Athens.