The Venetian Arsenal was the biggest and more efficient shipyard of the Renaissance, and the reason why Venice was capable of standing up to the Turks for three hundred years and seven wars.

San Lorenzo (?) galleasse in an illustration by eslovac artist Avor. It is based in a Venetian engraving. It is probably the galleasse of Antonio Bragadino that has sunk a Turkish galley. Next to it we can see another galleasse, and behind the galleys of the Christian line, that probably were not using the sail. At the far back we can see the Turkish watch tower at Point Scropha. The morning was clear, although the smoke from the cannons rose over the fleet.

Situated on islands in a lagoon at the northern extremity of the Adriatic Sea, the Republic of Venice depended upon sea power for prosperity and survival. Founded during the collapse of the Roman Empire, Venice retained ties with the Byzantine Empire and resisted incorporation into the medieval Germanic Holy Roman Empire.

In the age of the Crusades Venice battled both Muslim powers and Italian rivals. With its fleets Venice defeated the attempt of the Normans of the Two Sicilies to dominate the Byzantine Empire. Then in 1204 it diverted the Fourth Crusade to the conquest of Constantinople. Venice enjoyed a favored position in the eastern trade, which it generally maintained even after the Byzantines recovered Constantinople.

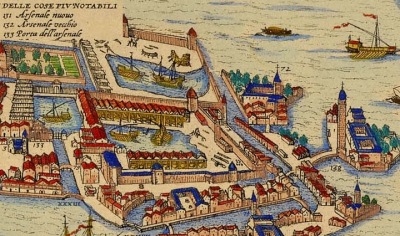

The need for specialized war galleys caused Venice in 1104 to establish a government-run arsenal and develop Europe’s first regular navy. The patricians who dominated Venice willingly captained its galleys and fleets. To control the Adriatic and the sea routes to the east, Venice established strongholds on the Dalmatian coast, Corfu, and the Greek coast, and colonized Crete and several Aegean islands. In 1480 Venice acquired Cyprus.

Venice emerged victorious in its struggle with Genoa and Padua over the eastern trade in the War of Chioggia of 1379–1381, in which the Venetians mounted for the first time cannon on their galleys. Threats from Milan drove Venice to acquire a mainland empire that stretched from Padua to Bergamo. Piracy remained a perpetual problem.

Under a supreme Captain General of the Sea, Venice’s fleet was organized into squadrons for operations against Uskoks (Dalmatian pirates), patrol of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas from Corfu under the Captain of the Gulf, and defense of Crete and Cyprus. As many as 50 galleys might have been operational at any time.

Extra hulls were mothballed in the arsenal, and for a major war 200 galleys might have become operational. While the elite volunteered to command, seamen and rowers came to be conscripted throughout the Venetian Empire, and marine infantry were hired from the Italian mainland or Germany. In 1545, as wages rose, Venice turned to convicts (but never slaves) to row its galleys. Cristoforo da Canal provided a treatise on administration and tactics, Della milizia marittima, which was written around 1550 and published in 1930.

In the fifteenth century the expanding Ottoman Empire, which captured Constantinople in 1453, posed Venice’s greatest challenge. Periods of peace and trade were interrupted by sharp wars. In August 1499 the Ottomans won the Battle of Zonchio and began to pick off Venetian strongholds in the Aegean and Greece. The 25–28 October 1538 Battle of Prevesa, fought in alliance with Genoa and Spain, proved another setback.

Venice resumed its precarious but lucrative peace with the Ottomans until the Ottomans demanded Cyprus in 1570. Through the pope, Venice forged an alliance that included Spain and most of Italy. Venice provided over half of the galleys and six galleasses in the allies’ victory of 7 October 1571 at Lepanto. By then Cyprus had fallen, though Crete was saved. Venice, whose aims differed from Spain’s, made peace with the Ottomans in 1573 and returned to trade.

In the same years piracy had burgeoned in the Mediterranean. It was committed not only by Uskoks (egged on by the Austrian Hapsburgs) and Barbary corsairs, but even by English and Dutch rovers, who operated from Barbary and marauded in large, well-gunned sailing ships. Venice’s former allies also proved a threat: the Knights of Malta disapproved of Venice’s trading with the Turks and attacked its shipping, and the Spanish viceroy of Naples waged in 1617–1620 an undeclared naval war against the Republic.

In 1645 the Turks invaded Crete to begin the War of Candia (1645–1669), which was named for the long siege of its capital. The Venetian navy that opposed them mustered over 60 galleys, four galleasses, and, in an admission of the gun-power of sailing ships, three dozen galleons. Venice won most of the naval battles, among them two in the Dardanelles in 1665 and 1666, but the Turks conquered Crete.

By the end of the seventeenth century, small states such as Venice could no longer match the greater states, which now had the requisite administrative structures to wage war on a giant scale. Having made a humiliating peace with the Turks in 1718, Venice eased its naval efforts, maintaining only minimal forces afloat. War expenses drastically increased the public debt, while neutrality in Europe’s constant dynastic conflicts enriched Venetian merchant shipping. The perennial threat from Barbary, despite the payment of tribute, led to renewed naval building in the 1780s. In 1792 Venice had four ships of the line and six frigates on patrol off Tunisia. But in 1797 Napoléon Bonaparte toppled the Republic, ending forever its independence. Its remaining war fleet was appropriated by France.

References

Lane, Frederic C. Venice: A Maritime Republic. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

Tenenti, Alberto. Piracy and the Decline of Venice, 1580–1615. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967.

Wiel, Alethea J. The Navy of Venice. London: J. Murray, 1910.