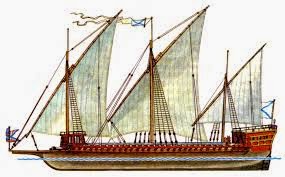

Russian Baltic Galley of 1720

When the Great Northern War ended in 1721, Russia had emerged as a major regional naval power. British and Danish naval forces cruised to counter the Russian sailing fleet, which was protected by new fortifications of Kronstadt on the island of Kotlin (1723). However, the general poverty of maritime resources, particularly seamen, made the development of Russian naval power very difficult and after the death of Peter I in 1725, the political support for the navy became extremely inconsistent. For the Baltic powers, moving armies and supplies through the shallow coastal waters was as important as defending the deep-water routes. Navies had to be balanced between the battleships, cruisers and inshore oared and sailing ships. Russian ships assisted in the siege of Danzig in 1734 and in the Russo-Swedish war which broke out in July 1741 their galley fleet was important. The Swedes underestimated Russian resistance in Finland and accepted a truce in the wake of the coup that brought the Tsarina Elizabeth to the throne. Hostilities resumed early in February 1742. A Russian galley fleet transported troops under General Keith westwards to attack Swedish positions at Åland. The Russian sailing fleet managed to lure the Swedes away from their position off Hango Head, which enabled more galleys to pass with reinforcements for Keith’s army. The Swedes were in disarray, but a peace was arranged before significant damage was done. Although active in the Seven Years War, the Russian sailing fleet really began to cause concern in the Baltic after 1780, when Catherine II began a major expansion of her fleet to assist her ambitions against Turkey.

Sweden faced a number of difficulties. There had been a growing divergence of priorities between the Swedish officer corps with its battleship base at Karlskrona aimed at Danish naval power and the government and army in Stockholm, who saw the amphibious Russian threat as the greater danger. Money was short and the navy had little interest in a coastal galley war. A 1722 plan by the College of Admiralty to build a galley fleet to counter the Russians was diluted by financial weakness. The battleships were high-quality vessels, but ageing and small. The lack of understanding between the navy and the army became apparent in the disastrous war against Russia of 1741–3. The galley fleet was reformed and in 1756 it was taken away from the navy and placed under army command. Its officer corps developed separately from the navy. In the same year a naval academy was established at Karlskrona. During the Seven Years War, the Swedes and Russians put pressure on the small Prussian flotilla in the Baltic. The main fear was the appearance of a British squadron in the Baltic to support the Prussians. While the Swedes and Russians operated together, their joint forces seldom exceeded 22 line against a non-existent Prussian battlefleet. The Swedish galley fleet performed well enough in 1759 against Prussian forces established at Stettin. A small action on 10 September ended in Swedish victory which consolidated Swedish communications between the homeland and the islands off the coast of Pomerania. In 1760 a Russian fleet of 21 line covered an attack on Kolberg that failed. Kolberg finally fell to the Russians in December 1761, but without much support from the fleet. Seapower against Prussia had not been particularly significant, but it remained critical to Sweden and Denmark in the defence of their homelands and interests in Pomerania and Holstein respectively. Despite cooperation against Prussia, suspicion of Russia remained a key part of Baltic diplomacy.

After the coup, which established Gustavus III with increased royal powers in 1772, the Swedish navy developed in line with Gustavus’ foreign policy ambitions. Gustavus’ direction was unclear–Russia or Denmark could be his target. The navy was important to either, but the officers of the galley fleet had been important supporters of Gustavus’ coup. New rules and organization were established in 1773. A royal inspection in 1775 led to the College of Admiralty moving from Karlskrona to Stockholm in 1776, to be closer to the court. The officer corps was reformed to make professional competence more significant in promotion. In 1781 the famous ship constructor, Fredric Henrick af Chapman (1721–1808), was appointed Director of Naval Construction at Karlskrona. Chapman had extensive theoretical knowledge of engineering sciences and since the 1760s had been designing and building vessels for inshore operations. In 1780 he was co-author of the plan approved by Gustavus for a new sailing fleet of battleships and frigates. Under his supervision, Karlskrona became one of the most extensive and modern yards in Europe.

The impact of Gustavus’ reforms are still a matter of debate, but by the summer of 1788 Gustavus was ready to attack Russia. While an army advanced through Finland and another, with the archipelago flotilla, was to move along the coast into the Gulf of Finland, a third army with the sailing fleet was to attack Kronstadt and land the army at Orainenbaum to advance on St Petersburg. The Russian fleet of 17 line under Admiral Greig met the Swedes, also with 17 line, off Suursaari island (Battle of Hogland) on 17 July. The battle was fought in line and after seven hours, the Swedes broke away in the darkness. Greig had done enough to avert the Swedish landing. Over the winter, Russian building of gunboats for its archipelago flotilla outstripped the Swedes. An action off Öland on 25 July 1789 between two evenly matched battlefleets was again indecisive, but the archipelago flotillas met in a decisive action just one month later on 24 August (Battle of Svensksund). Vice Admiral Nassau-Siegen decisively defeated the Swedish inshore flotilla. Swedish attempts to revive the plan of attack against Kronstadt in 1790 foundered in an indecisive attack on Tallinn in May, and a further attack on Russian battleships failed. Gustavus’ mistakes allowed the Russian sailing fleet to blockade his sailing and archipelago fleets in Vibourg Bay. On 3 July the Swedish sailing ships broke out and Gustavus was able to take the inshore fleet to Svenskrund. An impetuous attack on the Swedes on 8 July ended in disaster for the Russians. The peace treaty restored the boundaries to the status quo ante bellum. Both sides had shown that seapower–exercised by a combined force of battleships, cruisers and inshore craft–were critical to the projection of land power in the eastern Baltic, but both had also shown that their defensive capabilities far outweighed their offensive power. Russia remained a powerful force in the eastern Baltic, but not so powerful as to pose a vital threat to the interests of the other powers in the region. While the coasts of the Baltic remained open to traffic, and Russia remained prepared to trade its vital naval stores, it was in no one’s interest to become bogged down in a war that was so well suited to defence.