Robert Guiscard’s defeat of papal forces at Civitate (1053) was followed by campaigns to control the ports of southern Italy. He then used their fleets to support his nephew Roger’s conquest of Sicily and his own attempts on the Byzantine Empire. At Durazzo (1081) the Varangian Guard drove off the vaunted Norman cavalry before Guiscard achieved his victory.

THE NORMANS IN ITALY

The military impact of northerners is exemplified by the successes of the Franks (called for convenience Normans) in Italy. Arriving around 1000 they soon found themselves in demand as mercenaries, fighting for Lombard rebels against the Byzantine rulers of the region in 10 1617. They also fought on a Greek expedition to Muslim Sicily (1038-40) led by George Maniakes, alongside Harald Hardrada’s imperial Varangian Guard. After a dispute over booty, they defeated the Byzantines at Monte Maggiore in 1041, before Maniakes withdrew the rest of his troops to support his fruitless bid for the imperial crown in 1043.

It was clear that the Normans meant to stay. A certain Rainulf held Aversa from 1030, and Melfi was ruled by the sons of Tancred d’Hauteville, William, Drogo, and Humphrey. Another brother came south in c.l 046, Robert, nicknamed Guiscard (or ‘wily’), and outshone them all. These Normans were not united, but they could co-operate. In 1053, they defeated the forces of Pope Leo IX at Civitate, and both the pope and the German emperor were obliged to recognize the reality of Norman power. In 1059, Guiscard became a papal vassal and duke of Apulia, and in the same year Rainulfs nephew was made duke of Capua. Another Hauteville, Roger, arrived in 1056 and sought to make his name in Sicily. Allying himself with Abu Timnah, emir of Syracuse, he launched probing attacks into the interior in 1060 and early 1061. In May 1061, supported by Guiscard, he won a bridgehead at Messina. In 1064, they attempted a joint assault on Palermo, the key to the island, but despite Pisan naval assistance this failed and Guiscard returned to expelling the Greeks from southern Italy. His success was due to seapower, based on controlling Italian ports, and support from Sicily. Bari, the last Byzantine stronghold in Italy, was besieged from August 1068 until it fell in April 1071.

Immediately, Guiscard took his fleet, now augmented by vessels from Bari, for a combined attack on Palermo. This time it was successful. First, the Normans defeated a fleet from Zirid Tunisia, driving it into the harbour, breaking the defensive chain across its mouth and burning or capturing all the vessels. The city was blockaded by land and sea into starvation by January 1072. Back on the mainland, Guiscard employed the same blockade techniques to take Amalfi (1073) and Salerno (1076). Guiscard’ s ambitions now drew him east, for the Byzantine emperor, Alexius Comnenus, was deeply involved in recovering Asia Minor after a disastrous defeat by the Turks at Manzikert in 1071.

ASSAULT ON THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE

Guiscard launched a fleet across the Adriatic in May 1081 and besieged Durazzo (Dyrrachium, modern Durres in Albania). The Greeks’ Venetian allies proved more than a match for the Norman navy, but on land the Normans beat off a relief attempt by Alexius on 18 October, and the city fell the following February. Guiscard entrusted follow-up operations to his son, Mark Bohemond, but despite several successes in battle, the Normans were outmanoeuvred and lost the city in 1083. In 1084, Guiscard returned with a larger fleet and defeated the Greco-Venetian fleet off Corfu. Guiscard’s death from disease in 1085 ended the ensuing campaign. Yet the same year saw Roger victorious over a Muslim fleet off Syracuse whilst besieging the city. In 1090, Malta and Gozo were occupied easily and Sicily was entirely in his hands by 1093, enabling attacks upon North Africa.

The preaching of the First Crusade in 1096 drew Bohemond to make a legitimate expedition into the Byzantine Empire, from which he eventually wrung the city and territories of Antioch in Syria. Not satisfied with this prize, he launched his own ‘crusade’ in 1106, whose objective was Durazzo. He had made extensive preparations and gathered a large fleet, but Alexius Comnenus was ready for him. The Byzantine navy had been reconstructed, and after Bohemond settled down to besiege the city he found himself in turn blockaded and starved into a humiliating treaty. He died in 11 08 after a remarkable military career, but it was peripheral to the creation, in 1130, of the kingdom of Sicily, built upon Hauteville gains.

In seeking to explain such success it is tempting to believe the Normans’ own myth of their military virtue. The bravery of their men and the invincibility of their cavalry might seem reason enough. But good infantry were not easily defeated. At Civitate in 1053, the Swabian swordsmen put up a stiff resistance after the Lombards had fled. At Durazzo, the Byzantine emperor’s Varangians had driven the Norman knights back into the sea. When rallied, heroically, by Guiscard’s wife, they pinned the axemen in position by threatening to charge, while the crossbowmen shot down the now immobile infantry. There are obvious parallels with Hastings fifteen years earlier. It was the combination of arms which was important.

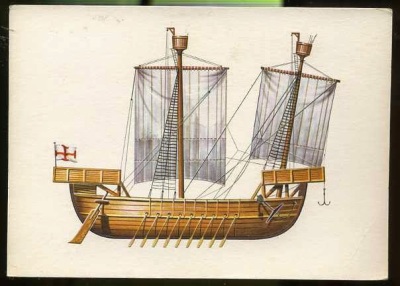

While repute in battle was clearly useful, most warfare revolved around sieges. It was in these operations that the Normans’ ability to use fleets was crucial to their success. Early in the siege at Bari, ships were chained across the harbour. In 1081, the ships were fitted with siege towers before the crossing, although a fierce storm stripped them away before they could be brought into use. While these techniques failed, and blockade proved better, the drive for innovation was impressive.

Norman adaptability at sea was expressed by their victory at Bari in 1071. The last Byzantine relief force was defeated at night, losing nine of their twenty vessels captured and one sunk. In the battle off Durazzo in 108 1, the Venetians had the advantages of a close formation known as the sea harbour, bigger ships, ‘bombs’ dropped through the enemy ships’ bottoms from the mastheads, and possibly Greek Fire. Yet by 1084, the Normans had developed a counter. Three squadrons of five large galleys, supported by smaller vessels, attacked the ’sea harbour’ at different points and won an overwhelming victory: seven out of nine Venetian vessels sunk and two captured.

The use of horse-transports combined Norman expertise on land and at sea. Already, in the 1061 assault on Sicily, 13 vessels carried 270 knights’ mounts to Messina in one crossing. By 1081, Guiscard may have had 60 horse transports and 1,300 knights. The ability to deliver battle winning troops by sea was emblematic of Norman military achievement.