I never saw so large and so beautiful a construction’ Luca di Masa degli Albizzi, Florentine Captain of the Galleys, 1430.

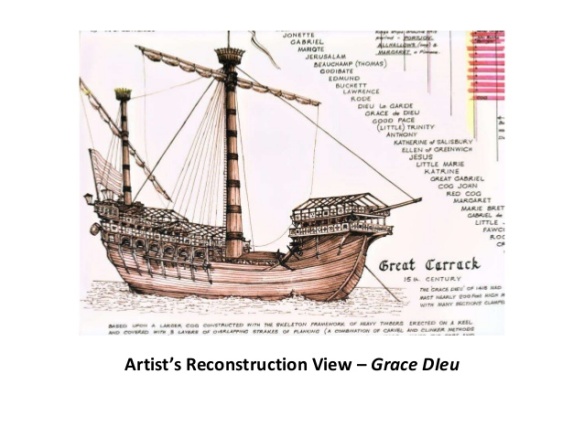

The greatest of all medieval ships, Henry V’s the Grace Dieu was a remarkable vessel of a similar size to HMS Victory, although with her towering castles she looked very different. Launched in 1418, she was more than two hundred feet long and had an estimated displacement of 2,750 tons. Her main armament consisted of archers who would fire down on enemy vessels from the imposing forecastle. In addition lumps of irons were hurled onto the ships below. She held the distinction of being the last ship to be built for an English king for fifty years.

On account of her undistinguished career, the size and design of Grace Dieu have attracted considerable criticism. In fact when she was completed, the role she was intended to perform no longer existed. Grace Dieu was the last of Henry V’s large ships including Trinity Royal, Jesus and Holy Ghost of the Tower. They were built to combat the formidable Genoese carracks, allied to the French, which contested control of the English Channel. The forecastle of Grace Dieu was fifty-two feet high and would have eclipsed the Genoese vessels, but by 1420 Henry had achieved undisputed mastery of the Channel.

Grace Dieu sailed on one voyage from Southampton in 1420 under the command of William Payne and was then laid up with the other large royal ships at Burlesdon on the River Hamble. There is no evidence she went to sea again, but nevertheless made a considerable impression on those who saw her. She came to a rather sad end, catching fire and burning out on the Hamble in 1439. No one believed the size of the ship until the wreck was surveyed in 1933. Previous examinations had wrongly concluded it was either a Danish galley or a mid-nineteenth century merchant ship.

Rebuilding a ship on the frame of an old one was a common maritime practice in the medieval period and indeed for many centuries afterwards. It was a cost-effective exercise, allowing for the sale of all the old scrap and outdated fittings, while reducing the investment needed for timber and other materials that could be reused. Much of Henry’s new fleet was built in this way, and as a high proportion of the vessels were captured as a result of either war or letters of marque (documents issued by countries authorizing private citizens to seize goods and property of another nation), this substantially increased the savings to be gained. The cost of rebuilding Soper’s Spanish ship, the Seynt Cler de Ispan, as the Holy Ghost, and refitting a Breton ship, which had been seized as a prize, as the Gabriel, amounted to only £2027 4s 111/2d. This compared favourably to the sums in excess of £4500 (excluding gifts of almost four thousand oak trees and equipment from captured shipping) spent building Henry’s biggest new ship, the 1400-ton Gracedieu, from scratch.

Unfortunately, neither the Holy Ghost nor the Gracedieu would be ready in time for the Agincourt campaign. Despite Catton’s and Soper’s best efforts, it was not easy finding and keeping skilled and reliable shipbuilders. On at least two occasions the king ordered the arrest and imprisonment of carpenters and sailors “because they did not obey the command of our Lord the King for the making of his great ship at Southampton” and “had departed without leave after receiving their wages.”

Henry’s purpose in all this was not to build up an invasion fleet as such: the magnitude of the transport required for a relatively short time and limited purpose made that impractical. His priority was rather to have on call a number of royal ships that would be responsible for safeguarding the seas. When they were not engaged on royal business, the vessels were put to commercial use: they regularly did the Bordeaux run to bring back wine and even hauled coal from Newcastle to sell in London. So successful was Catton in hiring them out between 1413 and 1415 that he earned as much from these efforts as he received from the exchequer for his royal duties. Nevertheless, their primary purpose was to patrol the Channel and the eastern seaboard, protecting merchant shipping from the depredations of French, Breton and Scottish pirates, and acting as a deterrent to Castilian and Genoese fighting ships employed or sponsored by the French.

On 9 February 1415 Henry V ordered that crews, including not just sailors but also carpenters, were to be impressed for seven of his ships, the Thomas, Trinité, Marie, Philip, Katherine, Gabriel and Le Poul, which were all called “de la Tour,” perhaps indicating that, like the king’s armoury, they were based at the Tower of London. A month later, the privy council decreed that during the king’s forthcoming absence from the realm a squadron of twenty-four ships should patrol the sea from Orford Ness in Suffolk to Berwick in Northumberland, and the much shorter distance from Plymouth to the Isle of Wight. It was calculated that a total of two thousand men would be needed to man this fleet, just over half of them sailors, the rest of them divided equally between men-at-arms and archers.

The reason so many soldiers were required was that even at sea fighting was mainly on foot and at close quarters. The king’s biggest ship in 1416 carried only seven guns, and given their slow rate of fire and inaccuracy they served a very limited purpose. Fire-arrows and Greek fire (a lost medieval recipe for a chemical fire that was inextinguishable in water) were more effective weapons but were used sparingly because the objective of most medieval sea battles, as on land, was not to destroy but to capture. Most engagements were therefore fought by coming alongside an enemy ship with grappling irons and boarding her. Imitating land warfare still further, fighting ships, unlike purely commercial vessels, had small wooden castles at both prow and stern, which created offensive and defensive vantage points for the men-at-arms and archers in case of attack.

Even with a newly revitalised and rapidly expanding royal fleet, Henry had nothing like enough ships to transport his armies and his equipment. On 18 March 1415 he therefore commissioned Richard Clyderowe and Simon Flete to go to Holland and Zeeland with all possible speed. There they were to treat “in the best and most discreet way they can” with the owners and masters of ships, hire them for the king’s service and send them to the ports of London, Sandwich and Winchelsea. Clyderowe and Flete were presumably chosen for this task because both had shipping connections: Clyderowe had been a former victualler of Calais and Flete would be sent later in the summer to the duke of Brittany to settle disputes about piracy and breaches of the truce. Flete was perhaps unable to fulfil this earlier commission, for when it was reissued on 4 April his name was replaced by that of Reginald Curteys, another former supplier of Calais.

- R.C. Anderson, ‘The Burlesdon Ship’, Mariner’s Mirror, Vol 20, No.2, 1934. M.W. Prynne, ‘Henry V’s Grace Dieu’, Mariner’s Mirror, Vol 54, No.2, 1968. N.A.M. Rodger, The Safeguard of the Sea, A Naval History of Britain 660-1649 (London 1997). S. Rose, ‘Henry V’s Grace Dieu and Mutiny at Sea: Some new evidence’, Mariner’s Mirror, Vol 63, No.1, 1977.

|

Grace Dieu statistics (estimated)

|

|

|

Period in service:

|

1420-1439

|

|

Displacement:

|

2,750 tons

|

|

Length:

|

66.4m / 218ft

|

|

Beam:

|

15.2m / 50ft

|

|

Complement:

|

250+

|

|

Armament:

|

3 cannon, archers

|