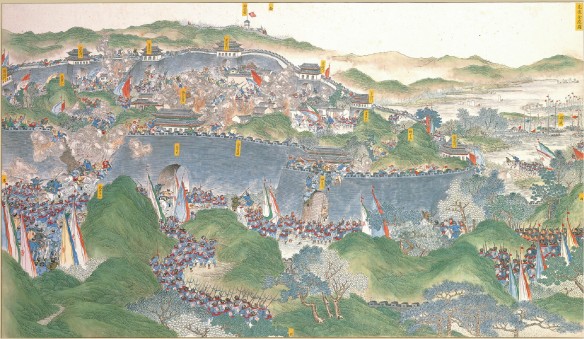

The Xiang Army recapturing Jinling, a suburb of the Taiping capital, July 19, 1864

Taiping soldiers, male and female, outside Shanghai

The Taiping “Rebellion” (1851–64), or “Revolution,” was a religious-based domestic uprising with ethnic—Han versus Manchu—overtones. Fought mainly with traditional Chinese weapons and tactics, it corresponded and overlapped with the Arrow War (1856–60), or second Opium War, which was China’s second anti-foreign trade war. The Manchus lost the Arrow War, but in the interim created China’s first modernized armies—the “Ever-Victorious Army” and the Xiang Army—in order to defeat the Taipings.

Although the military aspects of the Taiping and Arrow conflicts differ greatly, they will be treated together for several reasons. First, both conflicts owed their origins to the first Opium War. Second, both involved the use of military forces to oppose the Manchus’ Qing Dynasty in Beijing. Third, the Manchu Dynasty succeeded in using trade—in this case, the opium trade—to convince the foreign powers to oppose the Taipings, and in so doing retained their political domination over China.

The origins of the Taiping Rebellion can be traced to Britain’s victory over the Manchus in the Opium War, which revealed the Qing Dynasty’s internal weakness. The British victory gave Han Chinese hope that the Manchus had finally lost the “Mandate of Heaven” and that a new Han Dynasty might soon take its place. The effect of the Opium War on the Han Chinese leader of the Taipings, Hong Xiuquan, was especially profound: while Hong appears to have blamed himself for failing the Imperial Examinations three times during the 1820s and 1830s, after failing for the fourth time, in 1843, he angrily vowed to overthrow the Manchu government. Hong’s subsequent conversion to Christianity and the Taipings’ adoption of a unique mixture of Christianity and Confucianism also suggests the important impact of the Opium War on the Han Chinese people’s perception of westernization—in this case Christianity as the symbol of European culture—as a means of obtaining their political and cultural liberty from the Manchus.

The Arrow War similarly owed its origins to the Opium War. Unlike the Taiping conflict, the underlying issue in the Arrow War was the defense of foreign trade in China by insuring the safety of foreign ships from Taiping pirates. To guarantee free trade required treaty revision, prompting Great Britain and France to launch a military campaign, their main goal being to obtain greater trade privileges from the Manchus. In a marked departure from the Opium War, the Manchu Dynasty proved willing for the first time to adopt western military methods. During the Arrow War, the major military engagement—and one of the few in which the Chinese were victorious—was called the “Dagu Repulse.” However, in the long run the foreign forces outmaneuvered and defeated the Manchu military, even sacking and burning the Summer Palace during the fall of 1860.

Faced with international and domestic foes, the Manchus adopted a policy of playing the western nations against the Taipings by making major trade concessions—including legalizing opium in 1858. This was in marked contrast to the Han Chinese leaders of the Taipings, who, for religious reasons, adamantly opposed the importation and sale of opium. In return for trade concessions, therefore, the foreign powers sided with the Manchus and used their superior military might to oppose the Taipings.

By pitting the two sides against each other, the Manchus were able to defeat the Taipings while granting to the western nations only nominally greater trade advantages than they had held before. From a purely military viewpoint, the Manchu Dynasty in China was far too weak to oppose effectively any alliance between the Taipings and the western nations; but by exploiting the opium trade as its key negotiating point, Beijing not only kept the two groups apart, it eventually pitted them against each other. This policy ultimately led to the total defeat of the Taipings and to the formation of a new modus vivendi based on free trade with the western nations. The trading system that was put in force following the Arrow War would continue unchallenged for the next half-century. China’s diplomatic victory also gave new life to an Imperial dynasty that had seemed to be on the verge of collapse.

Death toll

With no reliable census at the time, estimates are necessarily based on projections, but the most widely cited sources put the total number of deaths during the 15 years of the rebellion at about 20–30 million civilians and soldiers. Most of the deaths were attributed to plague and famine. At the Third Battle of Nanking in 1864, more than 100,000 were killed in three days.

The rebellion happened at roughly the same time as the American Civil War. Although almost certainly the largest civil war of the 19th century (in terms of numbers under arms), it is debatable whether the Taiping Rebellion involved more soldiers than the Napoleonic Wars earlier in the century.