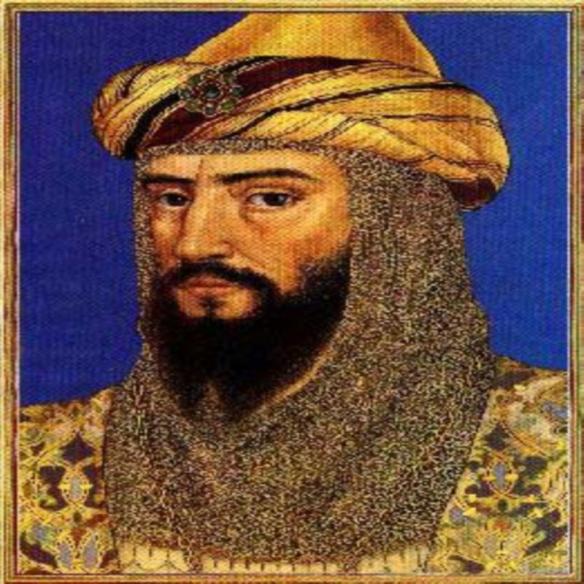

Salah ad-Din, or Saladin as he is known in the West, had been born in Tikrit in modern-day Iraq in 1137.

Saladin’s forces besiege the walls of Jerusalem.

Having set to rights the last of Nur al-Din’s legacy, Saladin faced a Frankish problem rather different from the one that had occupied the Almohads in al-Andalus. In Syria the Franks were comparatively isolated from their European sources of support; manpower and supplies were a constant source of weakness for them. Yet Saladin had the backing of the caliph in Baghdad and had methodically crushed or subdued all his Muslim foes in the region. The Almohads never had such luxuries, and so their campaigns against the Franks produced much less satisfying results than did the accomplishments of Saladin.

After touring the last of his newly conquered lands in northern Syria, Saladin was ready to focus on the Franks. He arrived in Damascus in May 1186. On the way, he had summoned his son al-Afdal from Cairo, who set out for Syria after mustering a small army. He was obliged to pause, however, as Frankish raids on the Egyptian border blocked his passage. Saladin was not particularly concerned. By instigating this raid, the Franks had broken the four-year truce they had once demanded and that had inconveniently tied his hands. If the Franks were going to engage in such practices, “then the wheel of ruin will turn against them,” his secretary smugly wrote. In August al-Afdal arrived in Damascus, while other of Saladin’s sons were sent to take charge in Aleppo and Cairo.

Much had happened in the Latin kingdom since Saladin first arrived in Syria nearly a decade earlier. By 1186 the leper-king Baldwin IV was dead, succeeded by his nephew Baldwin V, another child, who ruled only under the regency of Raymond of Tripoli. Then, when this Baldwin died a few months later, his mother, Sibyl, took the throne. As queen of Jerusalem, Sibyl came with her husband, Guy of Lusignan, whom she crowned in the summer of 1186 as king.

This reshuffling in the palace at Jerusalem resulted in two changes of direct interest to Saladin. On the one hand, it created a potential new ally in Raymond of Tripoli, the former regent. At court his talents were no longer needed, and he was put out to pasture. As a result he opened negotiations with Saladin and, it appears, entered into a treaty with him, opening passage to the Muslims through his lands around Tiberias. On the other hand, the new situation in Jerusalem also created a new enemy, in the form of Reynald of Chatillon. By 1186 Reynald could not really be called “new” as if he were an unknown quantity. Indeed his problem was that he was all too well known. Formerly prince of Antioch and now lord of Transjordan, Reynald was a hard-liner who came east with the Second Crusade and stayed on to make his name, eventually winding up as a guest in Nur al-Din’s prison in Aleppo for seventeen years. Later, as lord of Transjordan, he had outraged Muslims by sending a squadron of ships out on the Red Sea to attack merchants and pilgrims bound for Mecca. From his base at Karak, he followed the same modus operandi on dry land, harassing the caravans that crossed from Syria to Egypt, even while the truce between Saladin and Jerusalem was supposed to be in effect.

In this context Saladin’s options seemed fairly clear. He badly needed a victory against the Franks to silence those who criticized him for spending so much time at war with his fellow Muslims. Reynald’s actions were provocative, and Transjordan was an important jigsaw piece of territory connecting Saladin’s lands in Egypt to those in Syria. In itself the conquest of Transjordan would be a small gain against the Franks-but perhaps a threat there could lure the rest of the Franks out into the field. When Reynald captured a large Egyptian caravan and its guard, Saladin had his pretext. He demanded the immediate release of the prisoners, but Reynald refused, even (or perhaps especially) when Raymond of Tripoli arrived to serve as an intermediary. In March 1187 Saladin arrived at Karak for retribution and spent the spring harassing the countryside. The peasants fled in droves to Muslim territory. Meanwhile his son al-Afdal was mustering a large army at the Sea of Galilee; he led one impetuous raid to Saffuriya (ancient Sepphoris) in Palestine, where the Muslims overwhelmed a smaller Frankish force. Among the slain was the master of the military order of St. John, or Hospitallers, a valued Frankish commander. By May Reynald’s lands in Transjordan were devastated and virtually every stronghold, including Karak, was in Saladin’s hands. However, when news reached Saladin that his erstwhile ally Raymond of Tripoli had made peace with his fellow Franks, he knew that now was the time to strike at the Latin kingdom.

All of Saladin’s forces that were in the field, from Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia, made for Tiberias. Additional troops were on the move from Egypt if needed, and Saladin’s nephew in Aleppo made a truce with the Franks of Antioch to ensure his army would not be distracted. The sultan even sent a polite invitation to the Byzantine emperor, but he declined to join in. The Franks, led by King Guy, assembled at Saffuriya and had at their disposal the entire army of the Latin kingdom, including Templars and Hospitallers, assisted by much smaller contingents from Antioch and Tripoli. The exaggerated figures given by our medieval sources on the disposition of the Muslim and Frankish troops are hard to swallow, but Saladin’s army, soberly estimated at about thirty thousand, seems to have grossly outnumbered the combined forces mustered by the Franks. Indeed the very size of Saladin’s army may have added to his sense of urgency, as it would be very difficult to muster so many soldiers again and to keep them supplied and in the field for very much longer. If Saladin was to act against the Franks, he needed to act then and there.

In late June Saladin camped with his army at Kafr Sabt, to the southwest of Tiberias and the Sea of Galilee. There he controlled access to abundant sources of water and, more important, to the road running east from the Frankish camp at Saffuriya to the town of Tiberias. The city’s lord, the once-friendly Raymond of Tripoli, was of course away with most of his men in the camp of King Guy, but a small garrison, and Raymond’s wife, remained behind. Rather than stampeding into the Frankish camp, Saladin instead put Tiberias under siege in the hope of drawing the Franks into territory of his own choosing. The plan worked; after much argument, which even the Arabic sources take note of, the Frankish army marched east to relieve Tiberias. As the Franks strung themselves out along the road, a division of Saladin’s army maneuvered behind them to prevent their retreat. Other troops harassed them with feints and arrow fire as they traveled. In the heat of the season (now early July 1187) the battle became, at base, a battle about water. Saladin had ready access to his sources, but the Frankish troops were now sealed off from the secure sources at Saffuriya. Such springs that Guy could gain en route were utterly insufficient to the needs of his army; this seems to be what pushed him to make the fateful decision on July 4 to direct his army to the springs near the little village of Hattin.

At the Horns of Hattin, a double hill formed by the basalt rim of an extinct volcanic crater, the Frankish army saw that their progress was blocked even here. Trapped, unable to punch through the Muslim lines to Tiberias, most of the army retreated to the Horns, where Guy pitched his tent and the walls of ancient ruins atop the hill provided some semblance of cover. The Franks mounted numerous charges against the Muslim army, but Saladin’s men simply closed up around any men who came through. Only Saladin’s former ally Raymond III and a few of his men were allowed to pass through unharmed-a fact that cannot have buoyed Raymond’s stock among the few who survived the battle. The Muslim troops had the Franks on the Horns surrounded by fire and smoke, cut off from retreat or water, exhausted and decimated. By the end of the day the Muslims had managed to gain the summit. Saladin’s son al-Afdal later provided this dramatic eyewitness account:

When the king of the Franks was on the hill with that band, they made a formidable charge against the Muslims facing them, so that they drove them back to my father. I looked towards him and he was overcome by grief and his complexion pale. He took hold of his beard and advanced, crying out “Give the lie to the Devil!” The Muslims rallied, returned to the fight and climbed the hill. When I saw that the Franks withdrew, pursued by the Muslims, I shouted for joy, “We have beaten them!” But the Franks rallied and charged again like the first time and drove the Muslims back to my father. He acted as he had done on the first occasion and the Muslims turned upon the Franks and drove them back to the hill. I again shouted, “We have beaten them!” but my father rounded on me and said, “Be quiet! We have not beaten them until that tent [Guy’s] falls.” Even as he was speaking to me, the tent fell. The sultan dismounted, prostrated himself in thanks to God Almighty and wept for joy.

The Battle of Hattin left the Frankish military gutted and thereby opened the Frankish kingdoms to reconquest by Saladin’s seemingly unstoppable armies. It was celebrated in Saladin’s sword-rattling chancery as “a day of grace, on which the wolf and the vulture kept company, while death and captivity followed in turns. The unbelievers were tied together in fetters, astride chains rather than stout horses.” Those Franks who did not die that day were taken as captives to be ransomed or sold. The most prized were taken to Saladin’s tent to be dealt with personally; Guy and many other lords were eventually ransomed. Reynald of Chatillon did not join them. Instead, following the letter of Islamic law when dealing with dangerous prisoners, Saladin urged Reynald to convert to Islam and, when he refused, personally executed him, as he had twice vowed to do. It was the social implications of the act, not its finality, for which Saladin felt he should apologize, saying to Guy, “It is not customary for one prince to kill another, but this man had crossed the line.” The same process attended the execution of the Templars and Hospitallers, who were considered such a danger that Saladin personally ransomed any such prisoners found in the hands of his men, to ensure that they would meet their end. He also had any Turcopoles (Turkish light cavalry in the service of the Franks) executed as traitors.

Throughout Syria, it is said, the price of slaves plummeted as the markets were flooded with Frankish captives. According to one source, one Frankish prisoner was traded in exchange for a shoe. When asked, the captive’s seller explained that he insisted on the price because he “wanted it to be talked about.” The nonhuman plunder taken was also said to be considerable. Among the treasures was the relic of the True Cross, which the Franks had carried before them in battle. Its capture was precisely as devastating to the Franks as it was thrilling to Saladin’s subjects in Damascus, who suspended it upside-down on a spear and paraded it through the streets of the city. It was later sent by Saladin’s son al-Afdal as a trophy for the caliph of Baghdad and was never seen again-lost, one presumes, during the Mongol sack of 1258. At Hattin itself Saladin had a “Dome of Victory” constructed to commemorate what was already being seen as a turning point in his life; however, within a few decades, like much Saladin left for his descendants, it was in ruins.

By the end of 1187 Saladin’s armies had captured most of the territory that the Franks had taken since they arrived with the First Crusade. The cities of Syria and Palestine fell one by one, in diverse circumstances. In the wake of the debacle at Hattin, the mere sight of Muslim armies was often enough to convince Frankish leaders to surrender their towns, as at Acre. At Nablus the local villagers-almost all of whom were Muslims-blockaded the Franks in the citadel until one of Saladin’s commanders arrived and accepted their surrender. Jubayl, on the northern coast, surrendered as ransom for its lord, Hugh Embriaco, who had been captured at Hattin. A similar ploy was attempted in the south, where King Guy and the master of the Templars were trotted out to convince the garrison of Ascalon to surrender, but to no avail. Instead Saladin’s armies met fierce resistance, though the Franks there were eventually prevailed upon to surrender. Other cities likewise gave Saladin some serious resistance, as at Beirut and Jaffa. Then again, some places were simply passed over and saved for later, notably the port of Tyre, which Saladin reconnoitered but left untouched not once but twice as he crisscrossed the region. It was an act of expediency he would live to regret.