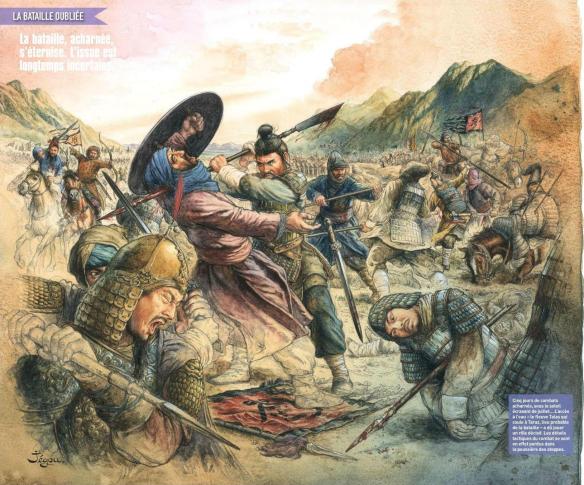

In 751 a Tang (T’ang) dynasty army commanded by Gao Xianzhi (Kao Hsien-chih), military governor of Anxi (An-hsi) in the Western Regions, met an Arab army in battle at Talas River near Samarkand. The Chinese were defeated. Although this was not a major military confrontation, it had great consequences.

Tang power and prestige stood at their zenith up to 750. Tang military forces had scored major successes and secured the frontiers from Tibet to Central Asia; the northern steppes were under a friendly semi-sedentary people called Uighurs, while the Khitans in the northeast and the Xixia (Hsi Hsia) in the southwest were contained. International trade flourished by land along the Silk Road, and by sea routes. However soon all would change. The aging Emperor Xuanzong (Hsuan-tsung), infatuated with a young concubine, the Lady Yang (Yang Guifei), had been neglecting his duties while her corrupt family and favorites dominated the government. The military system that had made the empire strong during the previous 100 years was deteriorating. Many of the frontier garrisons were manned by nomadic mercenaries and commanded by non-Chinese generals. Meanwhile Muslim Arab power had been expanding eastward.

The conflict began as one between two local states, Ferghana, a Chinese client state, and Tashkent. It led to battle between Ziyad bin Salih, governor of Samarkand under the Ummayyad Caliphate, assisting Tashkent, and General Gao Xianzhi and his Chinese forces. Gao was badly defeated when his ally the Western Turks defected to the Arabs and retreated across the Pamir Mountains. The battle was not significant in the short term, because the Arabs did not press eastward to threaten China, but because of what followed in the long term. In the same year, nearer to home, the aborigines in Yunnan in southwestern China revolted and declared independence, creating a state called Nanzhao (Nan-chao).

Finally in 755 the Turkic general and once imperial favorite An Lushan (An Lu-Shan) began a rebellion that captured both Tang capital cities and threatened the throne. The immediate result of events in 755 was the recall of Chinese forces from Central Asia, creating a political vacuum. That left the Arabs in a strong position. Likewise the power vacuum enabled the Tibetans and the Xixia people to expand their power at China’s expense. Even as an ally the Uighurs expanded their power at the Tang’s expense. Without Chinese military protection the Buddhist states in Central Asia would fall to the rising power of Islam. Chinese power would not return to the region for another 600 years.

Further reading: Beckwith, Christopher I. The Tibetan Empire of Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987; Grousset, René. The Empire of the Steppes, a History of Central Asia. Trans. by Naomi Walford. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994.

T’ang armies

The Sui dynasty was founded in northern China in 581 AD and had reunited the whole country by 589. Initial successes were followed by a disastrous war with Koguryo and several rebellions. A military family from the northern frontier succeeded in establishing the new T’ang dynasty, which united China by 623 and extended Chinese frontiers further than ever before. Sui and early T’ang armies were based on the fu-ping militia system, both infantry and cavalry being conscripted but thoroughly trained. The system could not cope with prolonged service on distant frontiers, however, and the militias were progressively replaced by professional troops until being abolished in 753. Some T’ang armies in the steppes were composed entirely of cavalry, though such armies were usually mostly Turkish auxiliaries. Other T’ang armies in Central Asia had all their infantry mounted. Sui armies must use infantry.

T’ang infantry were divided into pu-ping “marching infantry” and pu-she “foot archers”. Classification is awkward because it was the ideal that all troops should carry bows – even, apparently, if also armed with spears – but it is not clear how far this ideal was achieved. Some Sui cavalry carried lance, others sword and shield. Under the T’ang, most heavy cavalry were armed in originally Turkish style with lamellar armour, lance and bow; but occasional sources show lances only. Sui armies used wagon-laagers and chevaux-de-frise against Turkish cavalry, and T’ang forces also occasionally used defences. Mo-ho are the Manchurian tribes called Malgal by the Koreans. Some fought for the Sui against Koguryo and against Chinese rebels, and for the T’ang against Turks, Tibetans and Silla.