Arsites, satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia, had hastily summoned various generals to the town of Zelea (Sarikoy), about 20 miles from the Macedonian camp. Everyone present had an opinion about how to defeat the Macedonians, but the most prudent advice came from Memnon of Rhodes, the leader of a contingent of Greek mercenaries in the employ of the Persians. Memnon had once visited Pella and had experience of Macedonian military tactics. He knew that once Alexander ran out of the provisions he had brought with him he would have to forage for more. Therefore Memnon proposed to devastate the area by burning the crops and demolishing towns if need be, which would severely impede Alexander’s ability to feed his men and force them back to Macedonia.

Arsites naturally had no desire to bless Memnon’s scorched earth policy in his satrapy, nor did he take too kindly to his blunt warning that the Persians should not do battle against Alexander because their infantry was nowhere near as well trained and was outnumbered by the enemy. Alexander had perhaps 40,000 infantry to the Persians’ 30,000 or less. However, the Persians had 20,000 highly trained, tough Greek mercenaries, and they could also field 16,000 or so cavalry, compared with the Macedonians’ 6,000. Taking these factors into consideration Arsites decided that he had the edge over the invaders, especially as his men would be fighting on familiar terrain. Ignoring Memnon’s counterarguments, perhaps even because he looked down on Memnon as a Greek, Arsites gave the order to do battle.

The Persians took up a position west of Zelea, above the plain of Adrasteia, through which ran the Granicus River. Probably this was near the modern Dimetoka. There they encamped on the river’s east bank. Alexander took 13,000 infantry and 5,100 cavalry and marched to the west bank of the river either later in the afternoon or as dusk fell. The Granicus River was fast flowing and about three feet deep, but the entire riverbed was 80 feet wide. The topography of the area has changed little since Alexander’s time, so the river’s western and eastern banks were very steep and around 12 feet high, most likely covered in the same woodland and scrub as today. Crossing the river would have been a struggle at the best of times, let alone when an enemy army was ranged along the opposite bank, ready to take advantage of any Macedonian slips. That was why Parmenion tried to persuade Alexander to wait until he found another way around the enemy line. Parmenion’s advice was sound, but it was not what Alexander wanted to hear: he sarcastically retorted that he would never be able to live down the shame of halting at a stream like the Granicus after crossing the Hellespont.

At this point our major ancient writers for the battle disagree. Arrian states that Alexander engaged the Persians the same evening as he arrived at the river, while Diodorus has it that he waited until the next morning when he could lead the army across undetected. Most likely Arrian is correct because Alexander characteristically took an enemy by surprise. Besides, it is highly unlikely that the Persians would not have seen thousands of Macedonians making their way across the river as day broke. Diodorus further says that Arsites positioned his cavalry slightly back from the water’s edge and stationed his infantry on the hill above them, whereas Arrian puts the cavalry right on the water’s edge with the infantry behind. Diodorus’s account is more likely to be correct because the Persian infantrymen atop the riverbank would be able to bombard the attackers with missiles and disrupt their line rather than trying to charge it from behind their cavalry.

The odds of the Persians preventing Alexander’s advance were therefore excellent. He had to lead his army down the western bank and across the river, neutralize the enemy cavalry, and force his way up the opposite bank while at the mercy of spears and arrows launched from its heights. A stumble by any part of the phalanx would cause instant disruption to his line, and the ensuing chaos would practically hand victory to the Persians. On the other hand, Alexander was well used to rivers thanks to growing up in Macedonia, and he may well have been eager to fight the enemy here rather than somewhere else as Parmenion had suggested. He saw that the various bends of the river gave rise to bluffs that had more gentle slopes of gravel running down to the water, which were virtually opposite one another, and decided to take advantage of these natural ramps. His strategy was to lead his men down one of the gravel slopes to the riverbed. Then, with the cavalry protecting both flanks of the phalanx, the men would cross the river in a diagonal line, no doubt because of the current, to the nearest gravel bed on the opposite side to attack the Persian army. From Philip’s time the Macedonian phalanx had been trained to cross all manner of terrain, including flowing water, and Alexander was banking on it not missing a beat now.

Alexander’s line stretched for a little over a mile. He stationed the Thracian, Thessalian, and other Greek cavalry on his left flank, commanded by Parmenion. The right flank comprised the Macedonian cavalry, which Alexander formed into two groups, one under the command of Philotas on the extreme right and the other, immediately next to the massed phalanx at the center, under Amyntas. Next to him Alexander took up his own position. The cavalry was arranged 10 horses deep, and the infantry line, eight men deep.

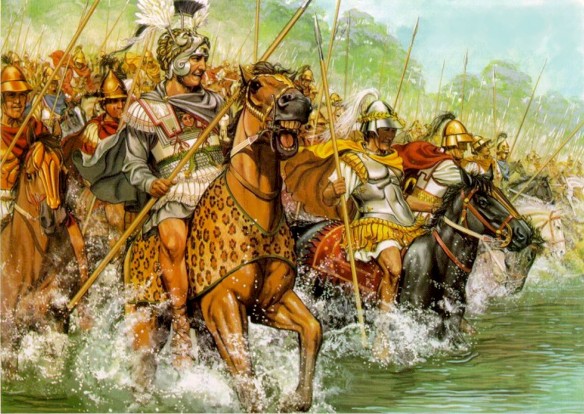

The Battle of the Granicus River witnessed Alexander’s introduction of the stratagem of a pawn sacrifice. He ordered Amyntas and a small strike force of fast cavalry (prodromoi) to cross the river ahead of the main army, thereby drawing the enemy’s fire. As Alexander had anticipated, the Persian cavalry charged Amyntas’s soldiers and even forced them back. In the meantime Alexander and the right wing began their move across the river, followed by the center and left flank, in a planned left-to-right diagonal line toward the opposite gravel beds. At that point the Persians realized that Amyntas’s brave action had merely been a distraction. Unable to regroup in time, the Persian cavalry fell victim to Alexander’s massed counterstrike, and as more of the Persian commanders were killed in the fighting when the two sides met, the cavalry lost heart and fled.

Now the battle became an infantry one. Parmenion had brought his left flank successfully across the river and regrouped into one continuous line that easily made its way up the west bank of the river to face the Persian infantry and Greek mercenaries. The Persian line became a bloodbath as the sarissas tore into the Persian troops, who were armed only with light javelins that were no match for the enemy’s long, deadly weapons. Thoroughly demoralized, and in an effort to cut their losses, they made their getaway after the cavalry. Alexander expected the Greek mercenaries under Memnon, who had not yet taken part in the fighting, to offer tougher resistance. Memnon at first sought terms, but Alexander was in no mood for leniency-he was also angry that Greek mercenaries were prepared to fight other Greeks. Without delay the king regrouped his line into its usual wedge formation and with the cavalry on the wings attacked the mercenaries head-on. It was said that Alexander’s men fought harder against Memnon and his men than against the Persians, and in one clash Alexander’s horse (evidently not Bucephalas) was killed under him. Eventually the king’s shock-and-awe tactics paid off, and 18,000 of the mercenaries were cut to pieces. Memnon managed to escape, but the surviving 2,000 mercenaries, including a contingent of Athenians, were captured and sent back to Macedonia to work in chains in the mines. Arsites, who had fled into Phrygia, took responsibility for the entire defeat and committed suicide.

“Of the Barbarians, we are told, 20,000 infantry fell and 2,500 cavalry. But on Alexander’s side, Aristobulus says there were 34 dead in all, of whom 9 were infantry”: These numbers were very likely exaggerated to magnify the Macedonian victory, but nevertheless the battle was a triumph of Alexander’s strategic planning, bold tactics, and daredevil courage. It was his first victory on Asian soil, and he had proved the fighting superiority of his army against a numerically greater enemy. Granicus began sounding the death knell of the Achaemenid dynasty.