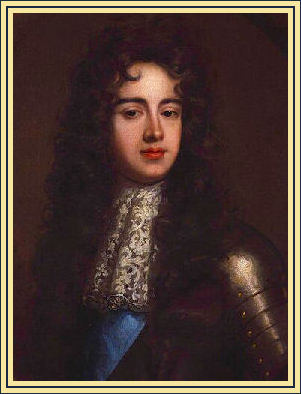

James Scott, Duke of Monmouth.

Battle of Sedgemoor

PRINCIPAL COMBATANTS: England vs. the duke of Monmouth

PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): Somersetshire, England

MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: Monmouth sought to succeed Charles II to the throne.

OUTCOME: The rebellion was crushed, Monmouth beheaded, and the other rebels punished.

APPROXIMATE MAXIMUM NUMBER OF MEN UNDER ARMS: Monmouth’s army, 9,000; royalist forces, 2,700

CASUALTIES: Monmouth’s army, 1,384 killed in action, 1,000 made prisoner, of whom 200 were executed and 800 transported to Barbados exile; royalists, 400 killed or wounded

James Scot (1649-85), duke of Monmouth, was proposed by the first earl of Shaftesbury as the heir to the throne of Charles II (1630-85) in preference to the Catholic duke of York, James (subsequently King James II [1633-1701]). When Monmouth attracted many supporters, he was threatened and had to flee for his life to Holland. He returned to England after the death of Charles II, where he proclaimed himself king and raised an army of 9,000 supporters. The duke of York, having ascended the throne as James II, sent an army under Louis de Durfort, the second earl of Feversham (1641-1709) to intercept Monmouth’s force. Colonel John Churchill (1650-1722), commanding the Household Cavalry, defeated Monmouth, largely with artillery fire, at the Battle of Sedgemoor, in Somersetshire, on July 6, 1685. Monmouth’s force was decimated, and although Monmouth himself escaped death in battle, he was soon captured and beheaded. Of 1,000 of Monmouth’s men taken prisoner, 200 were hanged and the rest shipped off to Barbados by judgment of Chief Justice George Jeffreys (c. 1645-89) in what came to be called the Bloody Assizes.

#

James, Duke of Monmouth, was Charles II’s eldest and favourite son, the product of his first serious love affair — in 1649, with Lucy Walter, an attractive, dark-eyed Englishwoman living in Paris. This was the year of Charles I’s execution, and it was later recounted that the nineteen-year-old prince, suddenly and tragically King in-exile, fell so deeply in love with Lucy that he secretly married her.

Charles always denied that Lucy was his legitimate wife, but he showed great favour to his handsome firstborn, awarding him the dukedom — the highest rank of aristocracy — when the boy was only fourteen, and arranging his marriage to a rich heiress. Sixteen years later, in 1679, Charles entrusted him with the command of an English army sent to subdue Scottish rebels, and the thirty-year-old returned home a conquering hero.

As the exclusion crisis intensified, the Whigs embraced Monmouth as their candidate for the throne — here was a dashing ‘Protestant Duke’ to replace the popish James — and Monmouth threw himself into the part. He embarked on royal progresses, currying popular favour by taking part in village running races, and even touching scrofula sufferers for the King’s Evil. But Charles was livid at this attempt by his charming but bastard son to subvert the line of lawful succession. He twice issued proclamations reasserting Monmouth’s illegitimacy.

The transition of rule from Charles to James II in February 1685 was marked by a widespread acceptance — even a warmth — that had seemed impossible in the hysterical days of the Popish Plot. ‘Without forswearing his Catholic loyalties, James pledged that he would‘ undertake nothing against the religion [the Church of England] which is established by law’, and most people gave him the benefit of the doubt. At the relatively advanced age of fifty-two, the new King cut a competent figure, reassuringly more serious and hardworking than his elder brother.

But Monmouth, in exile with his Whig clique in the Netherlands, totally misjudged the national mood. On 11 June that year he landed at the port of Lyme Regis in Dorset with just eighty-two supporters and equipment for a thousand more. Though his promises of toleration for dissenters drew the support of several thousand West Country artisans and labourers, the local gentry raised the militia against him, and the duke was soon taking refuge in the swamps of Sedgemoor where King Alfred had hidden from the Vikings eight hundred years earlier. Lacking Alfred’s command of the terrain, however, Monmouth got lost in the mists during an attempted night attack, and as dawn broke on 6 July his men were cut to pieces.

Nine days later the ‘Protestant Duke’ was dead, executed in London despite grovelling to his victorious uncle and offering to turn Catholic in exchange for his life. It was a sorry betrayal of the Somerset dissenters who had signed up for what would prove the last popular rebellion in English history — and there was worse to come. Not content with the slaughter of Sedgemoor and the summary executions of those caught fleeing from the field, James insisted that a judicial commission headed by the Lord Chief Justice, George Jeffreys, should go down to the West Country to root out the last traces of revolt.

Travelling with four other judges and a public executioner, Jeffreys started his cull in Winchester, where Alice Lisle, the seventy-year-old widow of the regicide Sir John Lisle, was found guilty of harbouring a rebel and condemned to be burned at the stake. When Jeffreys suggested that she might plead to the King for mercy, Widow Lisle took his advice — and was spared burning to be beheaded in the marketplace. Moving on to Dorchester on 5 September, Jeffreys was annoyed to be confronted by a first batch of thirty suspects all pleading ‘not guilty’: he sentenced all but one of them to death. Then, in the interests of speed, he offered more lenient treatment to those pleading ‘guilty’. Out of 233, only eighty were hanged.

By the time the work of the Bloody Assizes was finished, 480 men and women had been sentenced to death, 260 whipped or fined, and 850 transported to the colonies, where the profits from their sale were enjoyed by a syndicate that included James’s wife, Mary of Modena. The tarred bodies and heads pickled in vinegar that Judge Jeffreys distributed around the gibbets of the West Country were less shocking to his contemporaries than they would be to subsequent generations. But his Bloody Assizes did raise questions about the new Catholic King, and how moderately he could be trusted to use his powers.