The first conflict between the Roman Republic and the Kingdom of Macedonia started in 217 BC, while the Romans were already fighting against Hannibal and the Carthaginians during the Second Punic War. The second conflict with Carthage was particularly dramatic for Rome, involving Hannibal’s invasion of Italy and several heavy defeats for the legions. Trying to take advantage of the ongoing military difficulties of Rome, the Macedonians decided to attack the Republic while most of its legions were facing Hannibal. Philip V, King of Macedon, opened hostilities with Rome after the legions were utterly defeated at the Battle of the Lake Trasimene in June 217 BC. With the Carthaginian army seemingly running amok across Italy, the Macedonian monarch was sure that the Romans would be too busy to oppose his plans to conquer continental Greece and the Illyrian territories of the northern Balkans. During the preceding decades, the Roman Republic had already fought two victorious conflicts against the Illyrians and thus had reached the borders of Macedonia; in addition, the Romans had gradually obtained naval dominance over the Adriatic Sea. These expansionist moves were clearly unacceptable for the Macedonians, who considered the whole Balkans as part of their sphere of influence. The First Macedonian War started with a Macedonian invasion of the Illyrian territories on the Adriatic coast. For the first time in their history, the Macedonians built a large fleet, consisting of more than 100 warships, and disembarked their forces in Illyria. The ensuing land campaign, however, was a complete failure for Philip V, who achieved very little. In the summer of 215 BC, after the Romans had been crushed by the Carthaginians at the momentous Battle of Cannae, the Macedonians sent ambassadors to southern Italy in order to negotiate a military alliance with Hannibal. On their way back to Macedonia, the emissaries of Philip were captured by the Romans, who thereby learned of the new alliance between Carthage and Macedonia from the official documents that they were transporting. In 214 BC, a Macedonian army tried again to invade Illyria, but this time the Romans were able to disembark troops on the Balkan coast to oppose Philip’s offensive. Despite facing greater numbers, the Roman legions were able to defeat the Macedonians and restore Rome’s influence over Illyria. Philip V was obliged to abandon his expansionist plans, returning to Macedonia with his forces. During the following years, the Macedonians tried to penetrate Illyria from the south, while the Romans secured the area by concluding a military alliance with the Aetolian League. This was a confederation of Greek communities located on the southern borders of Macedonia, which had until recently been at war with Philip V. In 211 BC, the Aetolians allied themselves with Rome in order to fight more effectively against their common enemy, Macedonia. During the following year, the Kingdom of Pergamon also joined this anti-Macedonian alliance and sent its fleet to the Adriatic in order to support the Romans. The Macedonians had destroyed their own fleet after their first failed invasion of Illyria, having had no further use for it, so the allies controlled the Adriatic Sea without hindrance. The Macedonians fought in mainland Greece against the Aetolians for several years, obtaining the support of the Achaean League (another confederation of Greek communities and the mortal enemy of the Aetolian League). In 206 BC, after having suffered several heavy defeats, the Aetolians decided to make peace with Philip V: their Roman allies were heavily involved in campaigns against the Carthaginians and thus could not provide effective military support. The fleet of Pergamon had also returned to Anatolia, so the Aetolians were left to fight alone without allies. The First Macedonian War officially came to an end in 205 BC with the Treaty of Phoenice, according to which Philip V renounced his alliance with Carthage but could still exert direct influence over certain areas of Illyria. In practice, very little changed from the situation of 217 BC; it was by now clear, however, that Rome and Macedonia would fight a new war for dominance over the Balkans as soon as Hannibal could be defeated, which happened in 202 BC with the decisive Roman victory at the Battle of Zama in North Africa.

Sure enough, the Second Macedonian War broke out in 200 BC after Philip V invaded Attica and menaced the city of Athens. Advancing from their bases in Illyria, the Romans invaded Macedonia from the west but were not able to obtain a clear-cut victory over the Macedonians. In this conflict, the Roman Republic was again supported by the Kingdom of Pergamon and the Aetolian League: Pergamon sent its fleet and the Aetolians attacked Macedonia from the south. In 198 BC, after several months of inconclusive operations, the Romans landed in the Balkans with a substantial army. The Roman expeditionary force was able to achieve an initial victory in Epirus, at the Battle of the Aous, but the clash did not prove decisive. Meanwhile, at sea, the allied fleet of Rome and Pergamon reinforced Athens, which convinced the Achaean League to join the anti-Macedonian alliance. During the winter of 198–197 BC, the opposing sides tried to find a compromise in order to bring the hostilities to an end, but the peace negotiations came to nothing. The decisive clash of the Second Macedonian War was fought at Cynoscephalae in 197 BC. Here, for the first time on Greek soil, the famed Macedonian phalanx faced the Roman legions, with 26,000 Romans defeating 25,000 Macedonians. The battle took place on hilly terrain, where Philip V’s heavy infantry did not have enough space to manoeuvre effectively: this greatly advantaged the flexible Roman legions, which resisted the enemy charge and used their missile weapons (javelins) in devastating fashion. After this defeat, having also suffered significant losses on other secondary fronts, the Macedonian king decided he had no option but to make peace with Rome. Under the terms of the subsequent agreement, the Macedonians were forced to remove all their garrisons that were scattered across Greece and – for the first time since the age of Philip II – were obliged to acknowledge the political freedom of the Greek cities. Philip V also had to pay a large war indemnity and was made to surrender all his naval forces. The Macedonian Army, meanwhile, was reduced to just 5,000 soldiers and was officially forbidden from having war elephants. Thanks to their victory in the Second Macedonian War, the Romans could present themselves as the saviours of Greek freedom, yet all they had done was simply replace Macedonian predominance over Greece with their own.

Philip V died in 179 BC and his ambitious son, Perseus, became King of Macedon. Perseus had great plans for the expansion of his realm, his main objective being to restore Macedonia’s ancient glory. To achieve this goal, he spent most of his early reign trying to form a large anti-Roman alliance that comprised the Seleucid Empire as well as Greek cities, the latter having soon turned against the Romans after the Republic assumed indirect control over their territories. The Third Macedonian War duly broke out in 171 BC, the Romans once more being supported by their historical allies the Aetolian League and Pontus. While a Roman army disembarked in Greece, Macedonian forces invaded Thessaly from the north. Thessaly had been part of Macedonia’s territory since it was conquered by Philip II, and Perseus could not accept that it was now free from his political influence. It was in Thessaly that the first significant clash of the Third Macedonian War was fought, at Callinicus. The battle was a significant victory for Perseus, who defeated the Romans thanks to the superiority of his cavalry and light infantry. The war, however, was not yet over. In 169 BC, the Macedonians invaded Illyria, being by now sure that their home territories could no longer be attacked from Thessaly. The Macedonian invasion of Illyria was a success: Perseus’ troops conquered many enemy strongholds and captured more than 1,500 soldiers from the local Roman garrisons. During the winter of the same year, the Macedonians also invaded Aetolia, but this operation ended without achieving significant results. In the following spring, the Romans landed an army in Epirus and marched on Macedonia, but faced strong resistance during their advance across the mountains. Perseus’ light infantry fought with great distinction during these operations, greatly slowing down the movement of the Roman legions, to such an extent that the Romans were not able to invade Macedonia as they had planned.

The decisive year of the Third Macedonian War was 168 BC, during which a major pitched battle was fought north of Thessaly at Pydna. The Battle of Pydna is widely recognized as one of the most important military clashes of Antiquity, which can be clearly understood by analysing the numbers of troops involved on either side. Perseus deployed his whole military potential, with 39,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry, while the Romans confronted him with 36,000 foot troops and 2,600 mounted men. When the battle was over, Perseus had lost most of his forces, with 11,000 troops captured by the Romans. From a practical point of view, the Macedonian military potential had been broken decisively. After the defeat, Perseus retreated north to his capital of Pella with what remained of his cavalry; despite having suffered such severe losses, he was determined to continue resisting. However, the young Macedonian monarch was soon surrounded by Roman forces and had no choice but to surrender. Once captured, he was sent in chains to Rome, where he spent most of the rest of his life as a captive.

With the Third Macedonian War now over, the Romans were determined to avoid any future military resurgence by Macedonia. To that end, the Senate decided to break up the Kingdom of Macedonia into four cantons, which would be Roman protectorates. Rome now exerted control over all the natural resources of the country, in particular over its gold and silver mines. In addition, Macedonian territory was garrisoned by significant numbers of Roman troops. The peace conditions imposed by the Roman Republic were felt to be too harsh by the Macedonians, who were forced to become vassals of a foreign power after having been the dominant state of the Greek world for two centuries. Consequently, in 150 BC, a man named Andriscus, pretending to be a son of the former Macedonian king Perseus, guided a popular uprising in the four regions of Macedonia. His rebellion soon developed into a widespread conflict, which became known as the Fourth Macedonian War. Despite having only a handful of soldiers under his command, Andriscus was able to obtain several minor victories, and thus his uprising continued until 148 BC. In that year, the Romans were finally able to restore order in Macedonia by using very harsh repressive methods. Two years later, in a last desperate attempt to preserve their independence, the Greek cities of the Achaean League attacked the Romans, but were easily defeated by the legions. Roman troops besieged and destroyed Corinth in 146 BC, thus bringing to an end Greek freedom. In that same year, Macedonia was transformed into a Roman province and the Third Punic War was fought, which ended with the destruction of Carthage and the disappearance of the Carthaginians from the political scene of the Mediterranean. The fall of Corinth and the destruction of Carthage were two events that had a great symbolic impact at the time, with 146 BC marking the ascendancy of the Roman Republic as the leading power of Antiquity.

The Macedonian Wars had a deep impact on the destiny of the Thracians, whose participation in the four conflicts had been significant.During the Second Macedonian War, for example, some 2,000 Thracian warriors were part of the Macedonian Army during the Battle of Cynocephalae (197 BC). With the end of hostilities in 196 BC, the Thracians were freed from any form of Macedonian indirect rule. The various tribes, however, started to be increasingly worried about the expanding Roman military presence in the Balkans. With the defeat of Macedonia, a significant power vacuum had been created in Greece: the Romans wanted to fill this with their own legions, but the Seleucid Empire was also looking to conquer the southern portion of the Balkans. As a result, in 192 BC, hostilities broke out between the Roman Republic and the Seleucid Empire. Two years into the war, the Romans obtained a decisive victory over the Seleucids at the Battle of Magnesia in Anatolia. While returning to Greece, however, the victorious Roman legions were attacked by the Thracians, who had assembled an army of 10,000 warriors and waited for the Romans at a narrow forested pass in south-eastern Thrace. The tribal fighters attacked the Roman rearguard, which comprised a baggage full of riches that had been taken from the defeated Seleucids. The Roman rearguard was taken by surprise and routed; all its wagons were looted before the Thracians returned to their forest fastnesses prior to the arrival of Roman reinforcements. This little-known ambush was seen as a disaster by the Romans, and was something that they would never forget. While it had been a success for the Thracians, it was obviously not a decisive one for the destiny of their country.

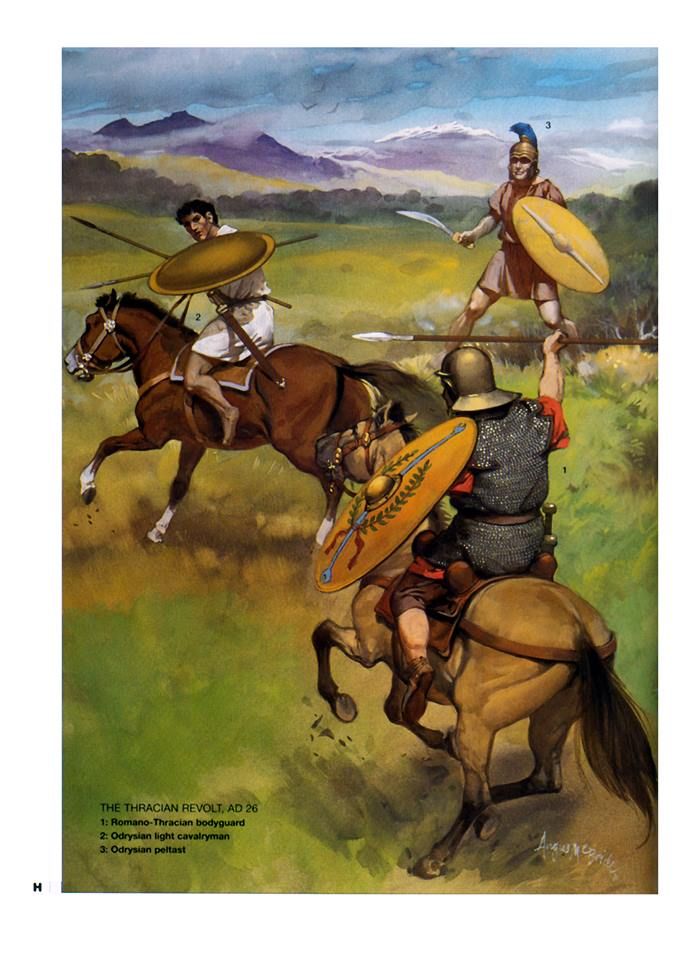

At the outbreak of the Third Macedonian War, Perseus’ forces comprised around 3,000 Thracians, who were later supplemented by another 2,000 fighters provided by the Odrysians (who were allies of Macedonia). At the Battle of Callinicus (171 BC), the Thracians in the Macedonian army secured a clear victory over the Romans: according to ancient sources, they returned from the battlefield singing, with hundreds of severed Roman heads. This was the second time that the Thracians had humiliated the Romans, but once again this Thracian success could not halt the expansionist policy of the Roman Republic. In 168 BC, a Macedonian army was soundly defeated by Rome at the Battle of Pydna, practically ending the Third Macedonian War and transforming the Macedonians into Roman vassals. At this point, with Macedonia having been conquered, the Thracians found the Roman legions at their frontier and thus feared being next in line for Rome’s expansionist moves. In 150 BC, an attempt to re-establish an independent Kingdom of Macedonia having provoked the outbreak of the Fourth Macedonian War, which lasted until 148 BC, the Thracians were again part of the anti-Roman front. As we have seen, the pretender to the Macedonian throne was defeated by the Republic and Macedonia was officially transformed into a Roman province in 146 BC. From that time onward, a state of constant war existed on the border between Roman Macedonia and independent Thrace. The Romans wanted to transform the various Thracian tribes into client communities, since they considered themselves the heirs of Macedonia’s political influence over Thrace. The Thracians, of course, had no intention of accepting the Romans as their overlords, and consequently soon started to launch aggressive raids against the province of Macedonia.

During the many ‘little wars’ fought against the Thracians, Roman armies were defeated on several occasions and even had one of their proconsuls killed. The Thracian warriors, with their elusive skirmishing tactics and great mobility, proved very difficult opponents for the Romans, who struggled in Balkan territory which was unknown to them. From 146 BC, the Roman Republic tried to recreate some sort of unified Thracian state, in order to transform Thrace into one of its vassal kingdoms. It would have been much easier for the Romans to control a single ‘puppet’ kingdom instead of keeping order among many warlike tribes. Around 100 BC, a new Odrysian Kingdom was created, but this did not last for long due to the internal divisions of the Thracians (most of whom were strongly against Rome’s indirect rule of their homeland). Around 30 BC, some form of Thracian Kingdom had been restored by the Romans; by this time, the Thracian tribes that were still autonomous had all accepted some form of Roman suzerainty. In 15 BC, the population of the Thracian Kingdom rose in revolt against the Romans and killed the puppet monarch who had been installed by Rome, but the rebellion was quickly crushed by the legions. Further Thracian uprisings took place during the following decades as the Roman presence in present-day Bulgaria became increasingly stable. In AD 12, Rome divided the territories of Thrace into two puppet kingdoms, but even this measure did not change the situation. The two Thracian realms soon started to fight against each other, and anti-Roman uprisings continued to occur with great frequency. In AD 45, a major new rebellion erupted in Thrace, which caused the death of one of the puppet kings chosen by the Romans. To stop the endemic guerrilla warfare that was ravaging the region, Emperor Claudius decided to transform Thrace into a Roman province in AD 46. Thracian uprisings and revolts continued for several years, but without achieving significant results. Like many other peoples living around them, the Thracians had lost forever their independence and were already slowly disappearing from history. During the following centuries, they were a fundamental component of the Roman Empire’s population.