The Demyansk Salient

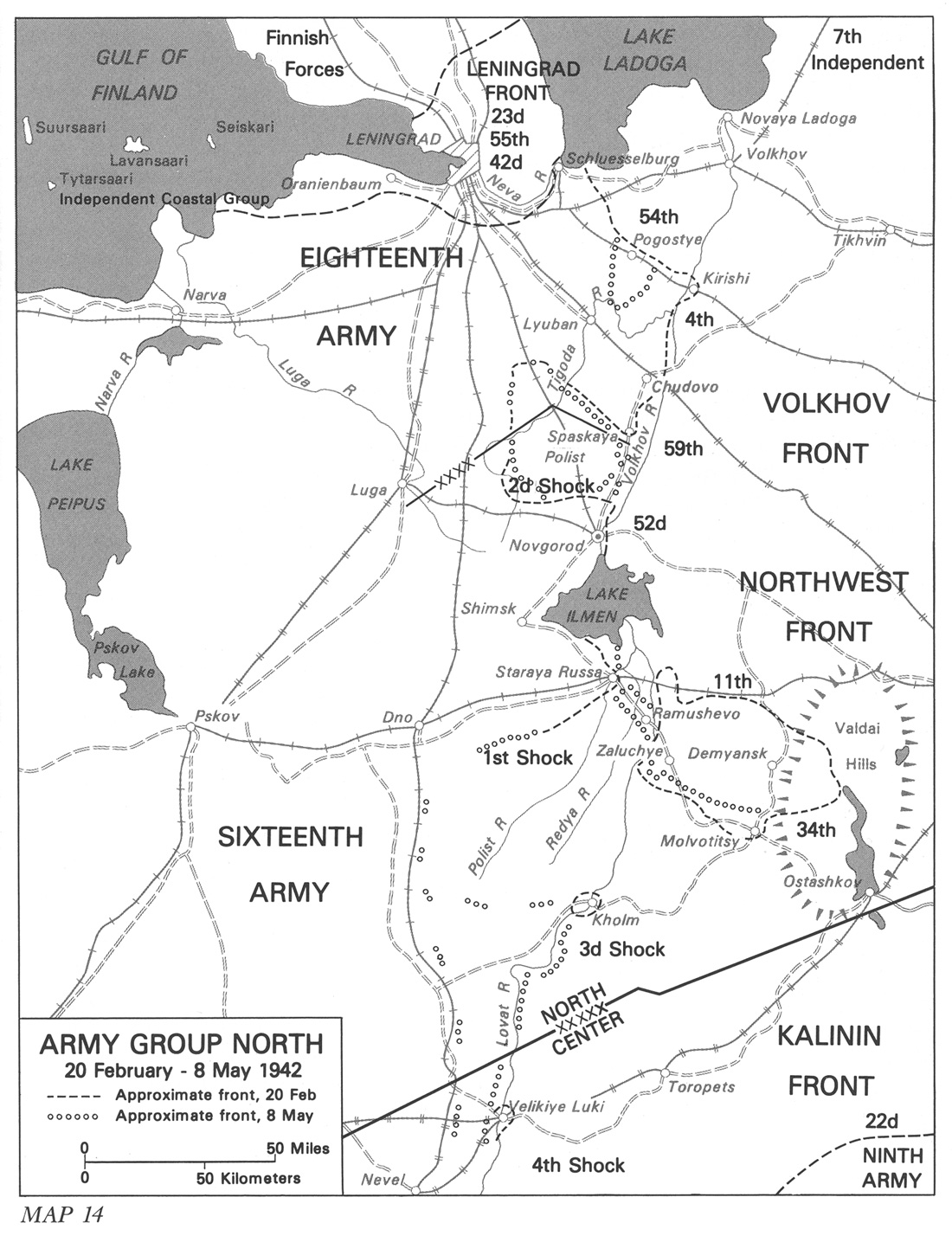

The Soviets had managed to drive a huge bulge into Army Group Center’s front during their 1941/42 winter offensive around Toropets in the northern part of the army group’s sector. This bulge actually extended into Army Group North’s sector, and the Soviets hurled nine armies against Army Group North in the same offensive. Their aims were to break the siege of Leningrad and push the front away from Moscow by levering the Germans from the strategic Valday Hills.

The Sixteenth Army tied into LIX Corps of Army Group Center in the vicinity of Velikiy Luki. It was a long front, since it incorporated the large salient extending towards the Valday Hills. This is not the place, for reasons of space, to discuss the lengthy fight for the Demyansk Pocket, or Salient, located about 100 miles (160km) south of Leningrad. It nevertheless produced some of the most ferocious fighting on the Eastern Front. Two German corps of six divisions were trapped in the pocket and these forces were later increased. Since the location of the pocket presented a German threat against the gigantic Toropets bulge, the Soviets were eager to eliminate it, as well as a pocket around Kholm that served to block a possible Soviet thrust into the rear areas of both Army Group North and Army Group Center. It was also a good jump-off position for a renewed German offensive against Moscow; this was probably the greatest worry for the Soviets, who misread German intentions in their 1942 summer offensive.

Leeb was very concerned about the situation in the Sixteenth Army area. He considered the Demyansk Salient valueless unless it was planned to move against the Toropets bulge. He called Führer headquarters on January 12, 1942, and proposed that his armies be withdrawn behind the Lovati River. Hitler immediately turned down the proposal, and Leeb thereupon flew to East Prussia to argue his case personally. Hitler again refused. Leeb then requested to be relieved of his command and Hitler agreed. Küchler was given command of the army group, and his place as commander of the Eighteenth Army was taken by General Lindemann.

While the Germans were aware of the opportunities presented by the Toropets bulge and the fact that the Soviets were overextended, they were unable to do anything about it. The German armies were bled white in the 1941 offensive and the subsequent Soviet winter offensive. The bloodletting could not be offset by replacements, which were slow in arriving, and there were virtually no reserves. Despite this situation, Hitler refused to abandon both Kholm and Demyansk. After being assured by the Luftwaffe that the reinforced First Air Fleet could deliver the required 240–65 tons of daily supplies to the two pockets, Hitler ordered them held until re lieved. This air supply operation used almost all of the Luftwaffe’s transport capability, as well as elements of its bomber force. The supply operations involved both airdrop and airlanding operations and were generally successful, primarily due to the weakness of the Soviet air forces in the area.

The Luftwaffe flew 33,086 sorties before the Demyansk Salient was evacuated in March 1943. The two pockets—Demyansk and Kholm—received 64,844 tons of supplies.28 A total of 31,000 replacement troops were brought in and almost 36,000 wounded evacuated. Several writers maintain that this was the first air bridge in history. This is not correct. In the invasion of Norway in 1940, an air bridge was established from Germany and Denmark to Norway. Five-hundred and eighty-two transport aircraft flew 13,018 sorties and brought in 29,280 troops and 2,376 tons of supplies. Yet the successful re-supply of the Demyansk and Kholm pockets had an ominous legacy. It confirmed in Hitler’s mind that encircled forces could hold out until relieved, and thus contributed to a policy that was to have disastrous results for hundreds of thousands of German soldiers.

Army Group North continued to worry about the Demyansk Salient. Küchler sent a personal letter to OKH on September 14, 1942, in an attempt to persuade Halder that continuing to hold the pocket was useless. Küchler hoped to use the divisions freed by a withdrawal from the salient to form reserves for the army group. Halder answered on September 23 after raising the issue with Hitler. Hitler’s earlier Haltenbefehl (hold order) remained unchanged. Halder acknowledged that Army Group North would gain 12 divisions by abandoning Demyansk, but pointed out to Küchler that such a withdrawal could also free 26 Russian infantry divisions and seven tank brigades.

The spectacular success of the German Army in the southern part of the Soviet Union during the summer of 1942 had expanded the territory conquered by German arms to the greatest extent of the war. However, the Germans had not achieved their primary aim: the destruction of the Soviet Army. The Soviets, now more mobile, had learned to avoid encirclements. The military situation that had looked so good and hopeful for the Germans in the East during the summer turned downright deplorable by the end of the year. By the middle of November, the situation at the front in southern Russia became critical for the Germans and their allies. A largescale Russian offensive began northwest and south of Stalingrad on November 19, 1942, by vastly superior Soviet forces. The Romanian Third Army was routed and overrun. Disasters quickly followed on the neighboring fronts on the Don and Volga, and the Soviet avalanche brought Italian, Hungarian, and also German divisions into a vortex of defeat. Battles of tremendous size developed in the last third of November between the Volga and Don.

The situation on the German central front in Russia became grave when on November 25, 1942, the Soviets began their expected offensive on a wide front south of Kalinin. The fact that the Soviets retained the capability to launch so many large-scale offensives after suffering repeated defeats and enormous losses during the summer was dismaying to the Germans and a surprise to the world.

Germans on the Defensive and Finnish Loss of Confidence

A Soviet offensive to open a land bridge to Leningrad began on January 16, 1943. While they broke through the “bottleneck” and managed to open a corridor to Leningrad on January 19, the ferocious fighting lasted until the end of March and cost the Soviets 270,000 casualties. The Germans managed to restrict the Soviet corridor to a width of 6 miles (10km), which could be brought under artillery fire, thus reducing its usefulness.

By mid-January 1943 the fighting had drained off the last army group reserves. General Kurt Zeitzler (1895–1963), the new OKH Chief of Staff, told Küchler on January 19, 1943, that he intended to raise the issue of evacuating the Demyansk Salient with Hitler. Army Group North had just suffered a serious setback south of Lake Ladoga, and Zeitzler and Küchler agreed that the principal reason for the setback was the shortage of troops and that the only way to avoid similar mishaps in the future was to create reserves by giving up the Demyansk Salient. However, it was obvious to both officers that Hitler would adamantly resist such a proposal.

On the night of January 31, 1943, after a week-long debate, Hitler finally accepted Zeitzler’s arguments. The earlier setback around Leningrad influenced Hitler’s change of mind. He was anxious to keep Finland in the war and this involved holding around Leningrad. Küchler decided to conduct a slow withdrawal which began on February 20, 1943. He then collapsed the salient in stages, completing the last one on March 18.

On February 3, the day after Stalingrad fell, there was a high-level policy meeting at Finnish military headquarters which included Mannerheim, President Risto Ryti (1889–1956), and several influential members of the cabinet. Those assembled concluded that there had been a decisive turning point in the war and that Finland should conclude peace at the earliest opportunity. Parliament was briefed in a secret session on February 9, 1943, to the effect that Germany could no longer win the war. Mannerheim explains that the briefing “had the effect of a cold shower” on the members of Parliament.

The Germans were fully aware of the importance of Leningrad for the Finns. Hitler therefore ordered Army Group North to prepare an offensive in late summer to capture the city. This was wishful thinking. Army Group North, fighting defensive battles, was primarily worried about what the Soviets would do. It was especially feared that the Soviets would strike at the boundary between Army Group Center and Army Group North south of Lake Ilmen. This would split the German front and pin Army Group North against the Baltic coast. Nevertheless, Army Group North proceeded to plan for the capture of Leningrad—code-named Operation Parkplatz. Much of the siege artillery brought north by the Eleventh Army was still in place, but Army Group North needed eight or nine divisions in order to launch the offensive. These were promised only after Army Group South had completed its operation to pinch off the large Russian salient at Orel west of Kursk—Operation Zitadelle (Citadel).

Zitadelle was launched on July 5, 1943, but after initial successes, fortune turned against the Germans as the Soviets launched a strong counteroffensive, and the conflict developed into the largest tank battle in history. The Germans were forced to retreat and the much hoped for success turned into a serious German defeat. As the fighting spread, the Soviets broke through the German front on the Donets River by the end of July. In August and September the German armies were driven back from the Donets River to the Dnieper River. By the end of September the Soviets had captured Kharkov and Field Marshal Günther von Kluge’s (1882–1944) Army Group Center was forced back to the edge of the Pripet Marshes.

Disastrous news for the Germans was piling up during the summer and fall of 1943. Sicily was invaded on July 9 and by August 17 the island was in Allied hands. Hitler’s ally Benito Mussolini was overthrown on July 24, 1943, and an armistice was signed with Italy. With their offensives making rapid progress in the south with enormous losses, the Soviets turned their attention to Army Group North. A full-scale offensive to lift the siege of Leningrad was launched on July 22, 1943. Repeated Soviet attacks south of Lake Ladoga were repulsed by Army Group North in July and August. However, the Germans knew that this offered only a temporary respite; OKH ordered Army Group North to prepare a new defensive line along the Narva River and Lake Peipus, 124 miles (200km) southwest of Len ingrad. These positions eventually became the Panther Line. This spelled the end of Operation Parkplatz.

OKW asked the Twentieth Mountain Army in Finland for its opinion about a possible withdrawal to the Panther Line. The answer stated that a withdrawal should not take place. The Twentieth Mountain Army argued that the Finns already felt let down by the failure of the Germans to capture Leningrad, despite repeated assurances to the contrary. Eduard Dietl, commander of the Twentieth Mountain Army, pointed out that after such a withdrawal the Finnish fronts on the Svir River and at Maaselkä would become indefensible and the Finns would be forced to withdraw. Dietl went on to caution that a likely result of a withdrawal to the Panther Line would be a Finnish approach to the Soviet Union for peace. If an acceptable peace was offered, the Twentieth Mountain Army would be cut off and a retreat to Norway over bad roads in wintertime would be extremely hazardous. Dietl’s warning was followed by a Finnish notice through Wipert von Blücher (1883–1963), the German Ambassador to Finland, that a withdrawal would have serious consequences for Finland. This could only be interpreted by the Germans as a forewarning that Finland would be forced to leave the war if the Germans withdrew to the Panther Line. Mannerheim also expressed concerns to General Erfurth about the reports of a pending German withdrawal. OKW sent an explanatory message on October 3, 1943, which stated that there were no intentions to withdraw, but that rear positions were being constructed in case of an emergency.

An OKW planning conference on January 14, 1943, made a complete revision of its view of Finland as a co-belligerent. It amounted to writing Finland off as an ally that could be counted on to carry its weight. The revised estimate concluded that the Finns would not be able to prevent setbacks in case of a major Soviet attack because their defenses were poorly constructed and they had few reserves. Despite the serious situation for Germany on other fronts, it was decided not to remove any units from the Twentieth Mountain Army.

A planning conference for the whole Scandinavian region took place at OKW in mid-March 1943. It included representatives from the OKW operations staff, the Chief of Staff of the Twentieth Mountain Army, and the operations officer of the Army of Norway. The conference recognized that the fall of Stalingrad had caused a decisive shift in Finnish opinion and that Finland’s government and military leaders no longer believed in a German victory. The Chief of Staff of the Twentieth Mountain Army opined that the Finns were preparing to exit the war and could only be prevented from doing so by a convincing German military victory in the summer of 1943, or by their inability to obtain acceptable peace terms from the Soviets.

Finnish leaders were fully aware that an offensive beyond the current positions would result in an immediate declaration of war by the United States, their only friend of any consequence in the Allied camp. The United States was viewed as Finland’s best hope of securing an acceptable settlement with the Soviet Union. Taken together with the view that Germany could no longer prevail in the war, this conclusion dictated a policy designed to keep the United States from declaring war. Finnish military leaders exercised great care not to put themselves in a position where they could be blamed by the government and parliament for a US declaration of war.

We can safely assume that Germany, the Soviet Union, and the United States were fully aware of the Finnish dilemma. Germany’s knowledge of the state of affairs is undoubtedly the reason they did not press the Finns to undertake offensive operations in 1943. The Soviet Union’s knowledge allowed them to take the risk of removing great numbers of troops from the German–Finnish fronts in 1943. The United States was the trump card and Ziemke is right when he writes that an offensive by the Finns in late 1943 “would in the long run have been suicidal for the Finnish nation.”

The OKW operations staff informed Hitler on September 25, 1943, that there were increasing signs that Finland desired to leave the war and it was expected that they would take action in this direction if Army Group North was forced to withdraw. This warning resulted in the OKW issuing Führer Directive 50 on September 28. It dealt with a possible Finnish collapse and the preparations required by the Twentieth Mountain Army for a withdrawal to North Finland and North Norway. Parts of the directive read: “It is our duty to bear in mind the possibility that Finland may drop out of the war or collapse… . In that case it will be the immediate task of the 20th Mountain Army to continue to hold the Northern area, which is vital to our war industry …”

Jodl visited Finland on October 14–15, 1943. The reason for the visit was apparently to try to bolster the confidence of the Finns in Germany and also to discuss Directive 50 with Dietl. Jodl pointed out to the Finns that Germany knew about Finnish efforts to get out of the war. Commenting on this, Jodl stated: “No nation has a higher duty than that which is dictated by concern for the existence of the Homeland. All other considerations must take second place before this concern, and no one has the right to demand that a nation go to its death for another.”

In his discussions with Dietl, Jodl pointed out that Hitler was adamant about holding the mining districts since the nickel was critical to Germany’s war effort. He opined that communications to the nickel mines could be kept open via Norway. Dietl replied that he had no confidence in the ability of the navy and air force to keep the Allies from cutting the sea supply lines around Norway, and that included the ore traffic. While agreeing with much of what Dietl had to say, Jodl did not believe it possible to withdraw the Twentieth Mountain Army by any other route than through northern Norway.

The situation south of Leningrad continued to deteriorate at the end of 1943 and the beginning of 1944. The Soviets made a deep penetration southwest of Velikiy Luki at Nevel on November 5, 1943. This penetration tore open the front of the Sixteenth German Army. Only a lack of immediate exploitation by the Soviets averted the disastrous possibility of their outflanking the Panther positions, thereby causing the collapse of Army Group North’s front.