Conquest of Sinai. 7–8 June 1967

Yet, as the saying goes, who dares wins. The Egyptians, listening to the excited voice on Radio Cairo announcing with more optimism than accuracy that their comrades had captured Beersheba, were quite unprepared for the sudden appearance of the Israeli tanks. Turrets swinging alternately right and left, the Centurions roared the length of the defile, a rain of coaxial machine-gun fire and HE shells keeping most of the defenders pinned down and unable to man their weapons. Having sustained few casualties and little damage, the group, consisting of eighteen Centurions, two Pattons and several half-tracks and jeeps, reached the outskirts of El Arish in mid-afternoon. Harel reported the fact to brigade headquarters from whence it was relayed to an astonished Tal, whose command group had just reached Rafa. Tal, recognising that Harel, now seriously short of fuel and ammunition, would remain in considerable danger unless he could be reinforced, ordered Gonen to reinforce him with the Patton battalion.

This was far easier said than done, for the Egyptians were now fully alert and fiercely determined that the defile would remain closed. An attack along the road, accompanied by a short hook through the soft sand to the south, resulted only in tanks being lost on mines or knocked out by anti-tank guns. The battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ehud Elad, was killed while personally leading the attack. Gonen decided to try again, smothering those positions closest to the road with mortar bombs while the Pattons used their speed and firepower to smash a way through. The result is vividly described by Shabtai Teveth in his book The Tanks of Tammuz.

‘The time was 1800 hours. The forward tanks were driving at a speed of 45 kph and the distance between each tank was growing. Major Haim [had taken over the battalion on Elad’s death] was worried that the Egyptians would be able to pick off each vehicle one after the other. About two kilometres down the road, close to the enemy’s artillery positions, he turned left off the road with part of the force and began shooting at the enemy artillery, tanks and anti-tank guns, which were now to his rear. He ordered the rest of the force, which had brought up the rear of the column, to carry on towards El Arish. Anti-tank guns were sent flying and dug-in enemy tanks reduced to flames. When he had a moment Major Haim reported to Colonel Shmuel [Gonen] on the situation and of his intention to destroy the defence zone from the rear.

‘“Leave everything, get to El Arish!” Colonel Shmuel ordered.

‘Again the distance between the tanks lengthened, with each tank driving through its own stretch of hell and the gunners working like men possessed.’

Suddenly, just as the sun was setting, the Pattons broke out of the defile and found themselves among Harel’s Centurions. Many had casualties aboard and all bore scars testifying to the ferocity of the encounter; incredibly, one waddled in with a smashed drive sprocket, lurching wildly from side to side.

Gonen had started to follow the Pattons with his command group and supply echelon but ran into such a hail of fire that he was forced to halt; the defile was closed again. Meanwhile, the 60th Armoured Brigade, commanded by Colonel Men, had been moving along a parallel axis inland. Tal ordered Men to attack the Jiradi position from the south, using his AMX-13 and armoured infantry battalions. The going in the soft dunes, however, was extremely difficult and at 1930 Men informed him that both battalions had stalled short of the objective and were out of fuel. Tal’s division was now stationary and dispersed across a wide area stretching from Rafah to El Arish and only prompt, decisive action would get it moving again. He withdrew Gonen’s armoured infantry battalion and a Centurion company from mopping-up operations at Gaza, directing his Chief of Staff to lead them personally through the traffic jam which had developed along the coast road. There was no time to be wasted in argument; those trucks which were slow in leaving the highway were bundled off it by the tanks.

With artillery support, the Centurions secured a lodgement in the northern defences of the Jiradi. At midnight, the armoured infantry arrived and, leaving their half-tracks, began fighting their way forward through trenches and bunkers, assisted by parachute flares. The Egyptians fought back stubbornly, but in such close-quarter night fighting their heavy weapons were less effective. As soon as a narrow corridor had been cleared along the road, Gonen set off with his fuel and ammunition lorries and by 0200 was clear of the defile. The Centurion and Patton crews at El Arish immediately began replenishing their vehicles, but if they were hoping for rest and sleep afterwards they were very much mistaken.

Meanwhile, to the south, Sharon’s division was heavily engaged at Abu Agheila. Here the Egyptian positions, lying on three successive ridges, had been prepared for all-round defence in great strength and depth. Ostensibly, the position could only be taken by direct assault, and then at heavy cost; that, however, was not the way the Israelis intended solving the problem. During the day Sharon’s Centurion battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Natke Nir, overran a battalion-sized outpost in a series of sharp actions then went on to cut the roads leading north to El Arish and west to Djebel Libni, shooting up fuel and ammunition dumps on the way; simultaneously, the divisional reconnaissance group and its AMX-13s cut the southern track to Kusseima. The Abu Agheila garrison was now in a situation where it could neither be reinforced nor withdraw. In the afternoon the 14th Armoured Brigade’s Sherman battalion closed up to the eastern perimeter, against which the assault was to be delivered that night by three infantry battalions, and began sniping at the enemy’s strongpoints.

As darkness fell the 99th Infantry Brigade left the civilian buses in which it had travelled to the front and marched up to its assault start lines, where it deployed with the two Sherman companies it had been allocated. At 2230 Sharon’s artillery opened a heavy preparatory bombardment and as the enemy guns began to reply the Israelis played their trump card. Exactly on time, flight after flight of helicopters clattered in to airland a parachute battalion just behind the Egyptian battery positions, which were quickly stormed. Concurrently, a Centurion-led battlegroup broke through the western perimeter and joined the paratroopers. As soon as the enemy artillery ceased firing, 99th Brigade and its supporting Shermans began fighting their way into the western defences, the tanks providing illumination for their gunners and the infantry with Xenon infra-red searchlights, while the infantry indicated their own progress with coloured light flashers. After several hours of fierce close-quarter fighting the two groups met in the centre of the position just as dawn was breaking. Those Egyptians that could mounted their vehicles and attempted to escape to the south-west, with Israeli tanks in hot pursuit. Abu Agheila, the key to central Sinai, had fallen.

Meanwhile, between Tal and Sharon, Yoffe’s division had been grinding its way westwards in low gear. It had traversed an area of dunes that the Egyptians considered to be tank-proof but which the Centurion’s cross-country performance and thorough route reconnaissance along the Wadi Haridin proved to be nothing of the sort, although it took nine hours to cover 35 miles. By 1845, having brushed aside such minor opposition as they had encountered, the leading elements of Yoffe’s 200th Armoured Brigade were in position covering the track junction at Bir Lahfan, which the Egyptians would have to pass through if they wanted to counter-attack at El Arish. It had, in fact, taken several hours for Mortagy to catch up with the situation, but early that evening he had ordered an armoured brigade and a mechanised brigade to move along the central axis and recapture El Arish in a dawn attack from the south. The Israelis watched them approach the junction in blaze of headlights then, at approximately 2300, opened fire. The headlights were hastily extinguished as the column scattered across the sand, but by now the flames from burning tanks and trucks provided an alternative source of illumination. Although the T55s possessed infra-red night fighting equipment, they were unaware that they were opposed by only twenty Centurions and did not develop an attack, seeming apparently content to engage in a protracted, long range fire fight. This suited the Israelis very well, as it enabled them to maintain their blocking role and simultaneously benefit from their superior gunnery techniques; it was ironic that the only Centurion to sustain serious damage was one which used its Xenon searchlight, and thereafter the use of light projectors was forbidden.

Furthermore, unknown to the Egyptians, Tal had despatched his replenished 7th Armoured Brigade south from El Arish and, having smashed through a defensive position near the town’s airfield, this began bringing additional pressure to bear on the Egyptian flank at about 0630. More of Yoffe’s division had come up and, as the light strengthened, the IAF came in to strafe and bomb. By 1000 the Egyptians had commenced a rapid and disorderly retreat towards Djebel Libni.

The situation within Mortagy’s army on the morning of 6 June can be summarised as follows. At Gaza the 20th (Palestinian) Division was fighting to the bitter end, which could not be long delayed. The 7th Division had been destroyed on the Rafah-El Arish axis, as had the 2nd Division at Abu Agheila. The 3rd Division’s camps near Djebel Libni were being savaged by Sharon’s and Yoffe’s tanks and that formation was pulling back as best it could. On the southern sector, the 6th Mechanised Division and Task Force Shazli had allowed themselves to be intimidated by a single Israeli armoured brigade, Colonel Albert Mandler’s 8th with only 50 Shermans at its disposal, with the result that the offensive thrust into the Negev had been abandoned and, at the most critical moment of the battle, several hundred Egyptian tanks were retained to meet a threat that did not exist. In the centre, however, the 4th Armoured Division still lay in the path of the advancing Israelis.

For his part, Gavish had every reason to feel satisfied with the events of the previous 24 hours. However, although the last of the Jiradi’s stubborn defenders had been overcome during the night and the 60th Armoured Brigade, having been replenished, had moved forward to El Arish, the very intensity of the first day’s fighting ensured that it could not be maintained on 6 June. Having been informed by prisoners that Mortagy had ordered all his troops to pull back and establish a line of defence covering the three passes that led from Sinai to the Suez Canal, the Tassa and Gidi in the north and the Mitla in the south, Gavish flew forward to brief his divisional commanders on the next phase of the battle. His orders were simple: Tal and Yoffe were to smash their way through the retreating Egyptians and seize the passes; Sharon was to complete mopping up around Abu Agheila, then drive the enemy towards Tal and Yoffe so that they would be caught between the hammer and the anvil. As far as possible, most of 6 June was spent in rest and replenishment, although on the coast road a battlegroup commanded by Colonel Israel Granit pushed on for a further 40 miles without encountering serious opposition.

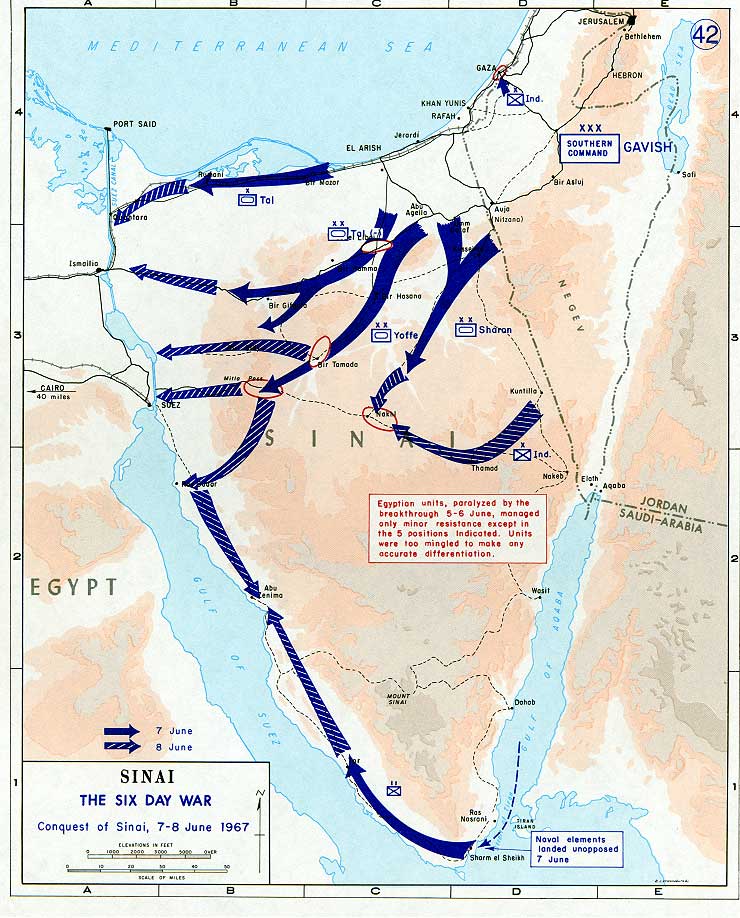

On 7 June the Israelis resumed their breakneck advance. Mortagy, allocated whatever armoured reinforcements could be scraped together in Egypt proper, committed them to the northern sector and did what he could to prevent the complete collapse of his army. The pace of the battle, however, was too fast for him and control slipped from his grasp as one formation after another went off the air.

Between Romani and El Kantara, Granit’s battlegroup, which had been reinforced by paratroopers who had driven west at top speed after the fall of Gaza, was temporarily halted by recently arrived enemy armour. While the tanks engaged in a gunnery duel, the paratroopers swung off the road in their jeeps and half-tracks, executing a wide hook onto the Egyptian flank to open fire with their recoilless rifles. Having thus eliminated the last obstacle in his path, Granit pressed on to El Kantara, becoming the first Israeli commander to reach the Canal.

Meanwhile, Tal’s division was heading straight for Bir Gifgafa, deliberately seeking battle with Ghoul’s 4th Armoured Division. In a stand-up fight lasting two hours Gonen’s Centurion and Patton crews demonstrated their superior gunnery, after which the Egyptians pulled off to the south in the fading light. While the tank battle raged, Tal pushed his 60th Armoured Brigade westwards, hoping to fall on his opponents’ flank, but the latter broke contact before the move could take effect. At about 0300 the leaguer of the brigade’s AMX-13 battalion, located in a hollow beside the road to the Tassa Pass, was entered by two Egyptian trucks with infantry aboard, heading west. Both burst into flames when they were shot up, but while the prisoners were being herded together tanks were heard approaching from the direction of the pass. They were T55s and formed the vanguard of a reinforcement brigade that had just entered Sinai. The guard tanks opened fire at once, their crews watching in horror as the rounds flew off the Egyptians’ heavy frontal armour. Since the leaguer was already illuminated by the burning trucks, the Egyptian gunners found plenty of targets for their return fire and soon several AMX-13s, a mortar half-track and ammunition vehicles were also blazing fiercely. Colonel Men, advised of the situation, despatched a Sherman company to the rescue and Tal ordered Gonen to further reinforce this with one of his Centurion companies. Before either could intervene, however, the remaining AMX-13s had scattered into the darkness and begun directing their shots at the enemy’s thinner side armour. After the first four tanks in their column had been knocked out in this way, the Egyptians halted and, following some long-range sniping, withdrew to the west. Their commander, evidently under orders to buy as much time as possible, deployed his armour in a series of tank ambushes over four miles in length at a point where the metalled road wound through a wide belt of dune country.

Next morning, 8 June, Tal’s division resumed its advance on the pass, spearheaded by 7th Armoured Brigade. The leading Centurion company, advancing beyond the bounds permitted by its orders, ran into the first ambush site and sustained some loss before it could be pulled back. Once the situation ahead became clear, Tal resorted to what he described as steamroller tactics. While the Centurions engaged each ambush site in a long range gunnery duel, followed by a simulated frontal attack that absorbed the defenders’ attention, the rest of the brigade executed a wide hook through the dunes and fell on the Egyptians’ rear. It took the Israelis several hours to fight their way through, by which time the sun was setting and the tanks required replenishment. Political considerations now began to intrude on the battle. Civilian radio programmes picked up on transistor radios indicated that in New York the Egyptian ambassador to the United Nations had requested a ceasefire, and before this could be imposed it was essential that the IDF should be firmly established on the Canal. The IAF had already confirmed that several more Egyptian positions lay ahead, but Tal, beefing up his reconnaissance group with six Pattons and a self-propelled artillery battery, sent it off into the darkness. The reconnaissance jeeps and the tanks worked as a team, the former flashing back signals with their torches whenever they reached a potentially dangerous area, which was then illuminated by the tanks’ infra-red light projectors and engaged with direct gunfire if the enemy was present. Most of the Egyptians, however, were already pulling back and little opposition was encountered in the pass. At 0030 on 9 June the reconnaissance group reached the Canal, destroying a guard tank beside which a lonely traffic control sentry mistakenly attempted to direct them across a bridge; replenished, the rest of the division arrived and quickly established contact with Granit’s battlegroup to the north.

If anything, Yoffe’s exploitation on 7 June was even more dramatic. His axis of advance took him in a south-westerly direction from Djebel Libni through Bir Hasana and Bir Tamada towards the Mitla Pass. It was also the direction in which most of the Egyptians in northern and central Sinai were attempting to retreat, harried constantly by the IAF. This proved to be something of a mixed blessing as, while it further demoralised the enemy and accelerated his disintegration, it also left the roads blocked with a tangle of burning wreckage through which the Centurions had to force their way. Rearguards were little in evidence so that from time to time the tanks, guns blazing, ploughed into the rear of a column. When this happened the Egyptians abandoned their vehicles and fled across the sand, leaving the road still further congested. Progress was so slow that at length Yoffe, realising that he would not reach the pass ahead of the enemy unless drastic steps were taken, despatched a task force, based on Colonel Iska Shadmi’s Centurion battalion, to drive through the Egyptians and, stopping for nothing, establish a roadblock at the eastern end of the Mitla. By the time he reached the pass fuel shortage and breakdowns had reduced Shadmi’s battlegroup to nine Centurions, two of which were on tow, two infantry platoons and three 120mm mortar half-tracks. Even as the roadblock was being set up, three more Centurions and two of the half-tracks ran out of fuel and had to be towed into position. Disorganised elements of the Egyptian 3rd Infantry, 4th Armoured and 6th Mechanised Divisions and of Task Force Shazli were now converging on the pass and, desperate to escape from the trap in which they now found themselves, they mounted repeated attacks on the tiny Israeli force barring their path. A handful of vehicles broke through before Shadmi’s tanks blocked the route with the burning wrecks of those that tried to follow. After this, the growing clutter of their own knocked-out tanks made each attack progressively more difficult for the Egyptians. Shadmi also had a powerful ally in the IAF, which strafed and bombed at will along the three-mile traffic jam that had developed in the approaches to the pass, creating unparalleled scenes of mechanical carnage. During the night most of the Egyptians abandoned their equipment and filtered through the hills on either side of the pass. Yet, it had been a very close-run thing, for when the rest of Yoffe’s division broke through at first light on 8 June Shadmi’s four remaining Centurions were down to their last few rounds.

After cleaning up the Abu Agheila area, Sharon’s division had headed south on the 7th, being joined by Mandler’s 8th Armoured Brigade, which had crossed the frontier near El Kuntilla. It had been anticipated that the Egyptian 125th Armoured Brigade, belonging to the 6th Mechanised Division, would put up a fight, yet all its tanks were found abandoned and in working order; the same division’s mechanised brigade was encountered near Nakhl and routed with the loss of 60 tanks, 100 guns and 300 vehicles. It remained only for Sharon’s troops to drive the remnants of Mortagy’s army westwards towards Yoffe and Tal, although for all practical purposes the fighting was over for a while.

The 1967 campaign in Sinai, lasting only four days, cost Israel 275 killed and 800 wounded. Total Egyptian casualties, including 5500 prisoners, were estimated at 15,000; approximately 80% of the Egyptian equipment in Sinai was destroyed or captured, including 800 tanks, 450 artillery weapons and 10,000 assorted vehicles. Not least among the IDF’s concepts of armoured warfare to be justified was that of leading from the front at all levels, albeit that several promising middle rank commanders had paid the ultimate price in so doing. Against this, risks were taken that could not have been justified in any other army and although it can be argued that such decisions were made with a full knowledge of the enemy’s weaknesses, it was folly to assume that these would never be eradicated. That particular chicken would come home to roost, with consequences that were to shake the entire Israeli nation, during Yom Kippur War of 1973.

Tal was to remain in command of the Armoured Corps until 1969. He served as the IDF’s Deputy Chief of Staff in the Yom Kippur War and was then closely involved in the development of Israel’s own main battle tank, the Merkava. He is widely regarded as being among the most successful practitioners of armoured warfare since World War II. Sharon again commanded an armoured division during the Yom Kippur War and played an important part in regaining the initiative for the IDF on the Suez Canal front. He subsequently entered politics and became Defence Minister, being noted for his uncompromising views. Yoffe also entered Parliament for a while, then became head of the Israeli Nature Preservation Authority, establishing wildlife reserves throughout the country. It was Gonen’s misfortune that he was serving as GOC Southern Command when the Egyptians effected their successful crossing of the Canal in October 1973, and it was inevitable that much of the blame for this and other Israeli reverses should be laid at his door. He was replaced by General Chaim Bar-Lev, but loyally agreed to remain at the front as the latter’s deputy.

Most Israelis had a sincere respect for the average Egyptian soldier, but not a lot for his officers, many of whom had abandoned their responsibilities and their men as they sought safety in flight. Well aware of these shortcomings, the Egyptian Army court-martialled no less than 800 senior officers who were either executed, imprisoned for life or dismissed in disgrace. Russian advisers also purged the officer corps of its more privileged members and insisted that the remainder should live and work among their troops. By 1973 the relationship between officers and men, and the general standard of leadership, had improved beyond recognition.

One officer who had escaped the odium of the 1967 defeat in Sinai was General Shazli, who had brought most of his troops home. In 1973, as the Army’s Chief of Staff, he was responsible for the detailed operational planning which resulted in the successful crossing of the Canal on 6 October. Believing, correctly, that he could not get sufficient tanks and anti-tank guns across in time to meet the inevitable Israeli armoured counter-attack, he equipped each of his infantry divisions with 314 RPG-7s and 48 portable AT-3 Sagger anti-tank guided weapons. The remarkable success of the latter caused a number of wild-eyed commentators to predict the demise of the tank (similar flawed prophesies had also marked the introduction of the anti-tank gun and nuclear weapons), yet the Israelis quickly discovered that by restoring the proportions of mechanised infantry and artillery in their tank-heavy armoured divisions that the enemy’s dismounted Sagger teams could be unsettled or neutralised by sustained fire.

Intervention by the United States and the Soviet Union prevented the Yom Kippur War being fought to a military conclusion. At a heavy cost in lives and equipment, both sides had won and lost territory, but the Egyptians were also satisfied that they had restored their honour. Taken together, this formed the basis for an honourable and lasting peace under the terms of which Israel withdrew from Sinai in exchange for Egyptian recognition and a secure southern frontier.