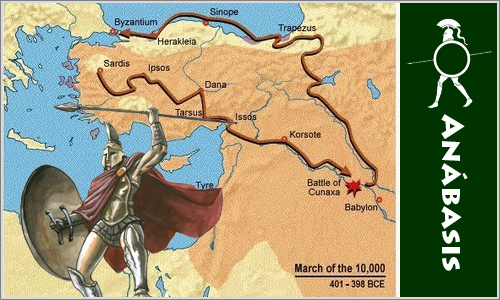

Route of Cyrus the Younger, Xenophon and the Ten Thousand.

Persian Immortals

Battle of Cunaxa – First phase of battle

Battle of Cunaxa – Second phase of battle

It all began with sibling rivalry. Darius II (r. 424-404 bc), Great King of Achaemenid Persia, had many children with his wife Parysatis, but his two eldest sons Arses and Cyrus got the most attention. Parysatis always liked Cyrus, the younger of the two, better. Darius, though, kept Arses close, perhaps grooming him for the succession. Cyrus he sent west to Ionia on the shores of the Aegean Sea, appointing him regional overlord. Just sixteen when he arrived at his new capital of Sardis, the young prince found western Asia Minor an unruly frontier. Its satraps (provincial governors), cunning and ruthless men named Tissaphernes and Pharnabazus, often pursued virtually independent foreign policies, and sometimes clashed with each other. There were also western barbarians for Cyrus to deal with. Athens and Sparta, now in the twenty-third year of their struggle for domination over Greece (today we call it the Peloponnesian War, 431-404 bc), had brought their fleets and troops to Ionia. The Athenians needed to preserve the vital grain supply route from the Black Sea via Ionia to Athens; the Spartans wanted to cut it.

The Achaemenids had their own interest in this war: after two humiliatingly unsuccessful invasions of Hellas in the early fifth century, they wanted to see Greeks lose. Hoping to wear both sides down, the western satraps had intermittently supported Athens and Sparta, but Darius desired a more consistent policy. That was one reason why Cyrus was in Ionia, to coordinate Persian efforts. He made friends with the newly arrived Spartan admiral Lysander. Persian gold darics flowed into Spartan hands; the ships and troops they bought helped put the Lacedaemonians on the way to final victory. In return, the Persians reasserted their old claims over the Greek cities of western Asia Minor. To safeguard their interests, Cyrus and the satraps relied on an unlikely source of manpower: Greek soldiers of fortune. Mercenaries were nothing new in the eastern Mediterranean, but by the end of the fifth century unprecedented numbers of Greek hoplites (armored spearmen) had entered Persian employment. Many of them garrisoned the Persian-controlled cities along the Aegean coast.

In the fall of 405 bc, as Sparta tightened its grip on Athens, Darius took ill. He summoned Cyrus home; the prince arrived at the fabled city of Babylon with a bodyguard of 300 mercenary hoplites, a symbol of what Ionia could do for him. On his deathbed, Darius left the throne to Arses, who took the royal name Artaxerxes II. The satrap Tissaphernes took the opportunity to accuse Cyrus of plotting against the new Great King. Artaxerxes, believing the charge, had his younger brother arrested. Parysatis, though, intervened to keep Artaxerxes from executing Cyrus, and sent him back to Ionia. Cyrus took the lesson to heart. The only way to keep his head off the chopping block was to depose Artaxerxes and become Great King himself. He set about making his preparations.

Across the Aegean, the Peloponnesian War was coming to a close. In May 404, Athens fell to Lysander. The city was stripped of its fleet and empire, its walls pulled down to the music of flute girls. For nearly a year following the end of the war a murderous oligarchic junta ruled the city, and with democracy restored the Athenians would begin looking for scapegoats; Socrates was to be one of them. The victorious Spartans faced other challenges. Having promised liberation from Athenian domination during the war, Sparta now found itself ruling Athens’ former subjects. The austere Spartan way of life provided poor preparation for the role of imperial master. Accustomed to unhesitating obedience at home, Lacedaemonian officials abroad alienated local populations with their harsh administration. Even wartime allies like Corinth and Thebes soon chafed under Sparta’s overbearing hegemony. Then there was the problem of Ionia. While their struggle with Athens went on, the Spartans had acquiesced in Persia’s expansionism, but now their attention began to turn eastward.

It was against this backdrop that, probably in February 401 bc, Cyrus, now an impetuous twenty-three-year-old, again set out from Sardis. His goal: take Babylon, unseat Artaxerxes, and rule as Great King in his brother’s stead. At the head of some 13,000 mostly Greek mercenaries along with perhaps 20,000 Anatolian levies, Cyrus marched east from Sardis across the plains of Lycaonia, over the Taurus Mountains through the famed pass of the Cilician Gates, through northern Syria, and down the Euphrates River valley into the heartland of Mesopotamia. Artaxerxes had been intent on suppressing a revolt in Egypt, but after being warned by Tissaphernes, he turned to face the new threat. Mustering an army at Babylon, the Great King waited until Cyrus was a few days away, then moved north against him.

In early August the two brothers and their armies met near the hamlet of Cunaxa, north of Babylon and west of present-day Baghdad. The heavily armed mercenaries routed the Persian wing opposing them, but to no avail: Cyrus, charging forward against Artaxerxes, fell mortally wounded on the field. In the days following the battle, the prince’s levies quickly fled or switched loyalties to the Great King, leaving the mercenaries stranded in unfamiliar and hostile territory. Their generals tried negotiating a way out of the predicament, but the Persians had other ideas. After a shaky six-week truce, Tissaphernes succeeded in luring the senior mercenary leaders to his tent under pretense of a parley; then they were seized, brought before Artaxerxes, and beheaded.

Rather than surrendering or dispersing after this calamity, though, the mercenaries rallied, chose new leaders, burned their tents and baggage, and embarked on a fighting retreat out of Mesopotamia. Unable to return the way they came, they slogged north up the Tigris River valley, then across the rugged mountains and snow-covered plains of what is today eastern Turkey, finally reaching the Black Sea (the Greeks called it the Euxine) at Trapezus (modern Trabzon) in January 400 bc. From there they traveled west along the water, plundering coastal settlements as they went. Arriving at Byzantium (today Istanbul) that fall, the soldiers then spent the winter on the European side of the Hellespont, working for the Thracian kinglet Seuthes. Finally, spring 399 saw the survivors return to Ionia, where they were incorporated into a Spartan army led by the general Thibron. In two years of marching and fighting, the mercenaries of Cyrus, the Cyreans, had covered some 3,000 kilometers, or almost 2,000 miles – a journey roughly equivalent to walking from Los Angeles, California, to Chicago, Illinois. Of the 12,000 Cyreans who set out with Cyrus, approximately 5,000 remained under arms to join Thibron. At least a thousand had deserted along the way; the rest had succumbed to wounds, frostbite, hunger, or disease.

The march of the Cyreans fascinates on many accounts. Cyrus’ machinations open a revealing window on Achaemenid dynastic rivalry and satrapal politics. His reliance on Greek mercenaries and Artaxerxes’ attempt to destroy them dramatically symbolize the convoluted blend of cooperation and conflict that characterized Greek-Persian relations between the first meeting of Hellene and Persian in mid-sixth-century bc Ionia and Alexander’s entry into Babylon some two centuries later. With its unprecedented mustering of more than 10,000 mercenaries, the campaign marks a crucial moment in the development of paid professional soldiering in the Aegean world.