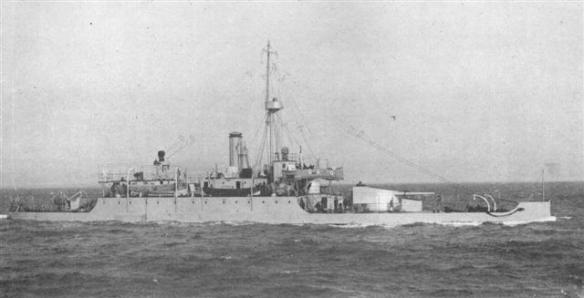

HMS Mersey, one of the monitors used for bombarding German positions on the Belgian coast in 1914.

English Channel

Though little noticed, the naval campaign in the English Channel was of vital importance in permitting the maintenance of the British Army in France. Like the North Sea campaign, it consisted largely of maintaining minefields. In this case, the need was to exclude surface raiders but particularly submarines. The Admiralty was conscious of the submarine danger from the outset.

Race to the Sea: September-Late November 1914

While the BEF was following events to the Marne and returning northwards, there had been coordinated efforts by relatively small forces of the Belgian field and fortress armies, French marines, Royal Marines, the Naval Brigade (sailors half retrained as infantry), the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and vessels of the Royal Navy. The aim was to support Antwerp, so tying up German forces and protecting the coast from occupation which would permit its harbours to be used by U boats and prevent their use in supplying a British army. This much and the importance of Calais and Boulogne-sur-Mer in supplying the BEF were perceived at the time.

It is also true that in order to maintain a British army in France at all, the allies had to control the English Channel. To do this, particularly against U boats, the Strait of Dover had to be controlled. For this, its two coasts had to be occupied by the Allies so that a barrage of vessels, mines and nets could be maintained up to the two coasts. In the event, this aim of retaining control of the French coast was achieved by coordination between naval and military forces of Belgium, France and the United Kingdom and no French port was lost. How much of this aspect was understood before the event is not clear. It was perhaps, so obvious, in the Admiralty at least, that it was not stated explicitly. Certainly, the U boat threat was well appreciated at this stage but the First Lord’s account of the time and its events makes no mention of the need to stop the threat at the strait.

These considerations made crucial the BEF’s return to the north before the fluid situation there had solidified into a line reaching the coast west of Dunkirk. On the whole, the German forces significant in this aspect of the ‘race’ came from eastern Belgium, having been occupied there by operations associated with the resistance of Antwerp.

During the Battle of the Frontiers and subsequent operations in 1914, the Humber class monitors were all employed in bombarding German batteries and positions under the command of Rear-Admiral Horace Hood.

On 10-12 October all three ships were ordered to Ostend, to cover the re-embarkment of the Naval Division and the evacuation of British personnel based at Ostend. They were then placed at the disposal of General Rawlinson, who was worried that he might have to evacuate by sea. In the event, his troops (the 7th Division and 3rd Cavalry Division) were able to join up with the rest of the BEF around Mons. They were then ordered back to Ostend (12 October) to help the Belgian government evacuate to Dunkirk, but didn’t arrive in time to take part in that operation.

On the night of 16-17 October all three ships were ordered back to the Belgian coast, from their base at Dover, to help the Belgian army fighting on the Yser. The monitors showed their limitations that night, being unable to leave port until the end of the day, arriving off the Belgian coast on 18 October. They were heavily involved on the Belgian coast on 18-20 October. They then had to be sent to Dunkirk to collect fresh ammunition, but were back in place by 22 October. By now Admiral Hood, commanding off the Belgian coast, was beginning to worry about winter storms that had the potential to sink the monitors, but HMS Mersey and HMS Humber remaining in place until early November. HMS Severn had to be sent home on 24 October to shift her guns. The threat from the weather was demonstrated again on 25 October when the two remaining ships became trapped in Dunkirk.

The monitors provided vital artillery support during the fighting on the Yser. The retreating Belgian army had lost much of its heavy artillery, and so relied on the naval forces to provide some firepower. If not always hugely effective, the naval guns did provide a vital boost to morale on the ground and on 28 October they played a key role in repelling a German attack that took place after the lock gates on the Yser had been opened to flood the area but before the floods had risen.

In early November HMS Humber remained off the Belgian coast, while the Mersey returned to Dover. The Humber’s guns were in better condition than those on her sister ships and she was the only member of her class to retain the twin gun turret.

HMS Venerable was a London class battleship that was heavily involved in the fighting on the Belgian coast in 1914-15 before serving off the Dardanelles and in the Aegean. Like the rest of her class she formed part of the 5th Battle Squadron of the Channel Fleet in August 1914, helping to protect the BEF as it crossed to France. Later that month she was used to transport part of the Portsmouth battalion of marines to Ostend.

By late October she was at Dover, serving as the flagship of Admiral Hood. This was a crucial period during the Race to the Sea, and on 27 October the Venerable anchored off the Belgian coast to help support the Belgian army in the battle of the Yser. The sluice gates had been opened to flood the area in front of the Belgian lines, but the water had not yet risen high enough to stop the Germans attacking. HMS Venerable took part in the bombardment of German positions from 7am to 8.15am. At that time a submarine was spotted, and the Venerable was sent to Dunkirk. At that time Admiral Hood felt that his smaller ships were doing that was needed. The Venerable rejoined the bombardment on 28 October, and remained until 30 October. On that day the seaplane carrier HMS Hermes was lost, and it was decided to withdraw the larger ships. Hermes was being used to ferry aircraft to France. On 30 October she arrived at Dunkirk with one load of seaplanes. The next morning she set out on the return journey. She was then recalled because a German submarine was known to be in the area, but before the order could be obeyed, she was torpedoed by U-27 off Ruylingen Bank. She sank with the loss of 22 of her crew.