Map of the assault on the Merville Gun Battery 6 June 1944

The lengths the Germans were going to in order to protect the battery, combined with the information provided by the Resistance, was enough to convince Morgan that the guns at the battery must be of 150mm calibre. When considering the significance of artillery, size matters. The circumference of the barrel dictates the weight and the explosive content of the shell, which in turn dictates its lethal effect. The weight of the projectile it fired meant that a shell bursting from a 150mm gun would have a lethal splinter distance radius of up to 200 metres. A salvo from four 150mm guns, firing in close proximity, could spread their jagged metal shrapnel over the area of a football pitch and would easily devastate a unit of infantry advancing over an open beach in a matter of minutes.

The existence of the battery, set back a mile from the coast, presented a significant threat to the landings and it was vital that it was eliminated before the troops touched down on the beaches. Bombing lacked precision and offered no guarantee when the casemates could withstand anything but a direct hit from the heaviest Allied bombs. Morgan therefore needed an insurance plan that the guns would be put out of action before the troops landed on the beaches. A pre-emptive attack launched from the sea entailed too much risk; getting a raiding party to the battery undetected would be no easy task and could alert the Germans in advance of the landing of the main invasion force.

Morgan’s bosses shared his concern and had no illusions about the hazardous nature of mounting an amphibious landing on a defended shoreline against fifty enemy divisions who were expecting an invasion. General Dwight Eisenhower’s appointment as Supreme Allied Commander of the invasion had been confirmed at the Tehran Conference in December 1943, where Churchill, Stalin and Roosevelt decided to open the second front. Ike had arrived in Britain in January 1944 to assume command of the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) at the same time as General Bernard Montgomery returned from commanding the 8th Army in Italy to take over command of the British contribution to the landings. As well as commanding 21st Army Group, Montgomery had been selected to command all the Anglo-American land forces under Ike and was tasked with overseeing the planning for the entire operation.

The experience of Dieppe and near disaster of the invasion of Sicily and Italy a year earlier increased Ike and Monty’s apprehension of what the Allies were about to undertake. If the invasion failed the implications for the conduct of the war would be significant: an Anglo-American landing could not be reattempted for some considerable time, and defeat in France would allow Hitler to transfer the bulk of his divisions to face the onslaught from the Red Army in the east. Consequently, like the Germans, the Allies saw the success or failure of the invasion as a strategic decision point and agreed with Morgan on the need to eliminate as many risks as possible to get the maximum number of troops safely ashore.

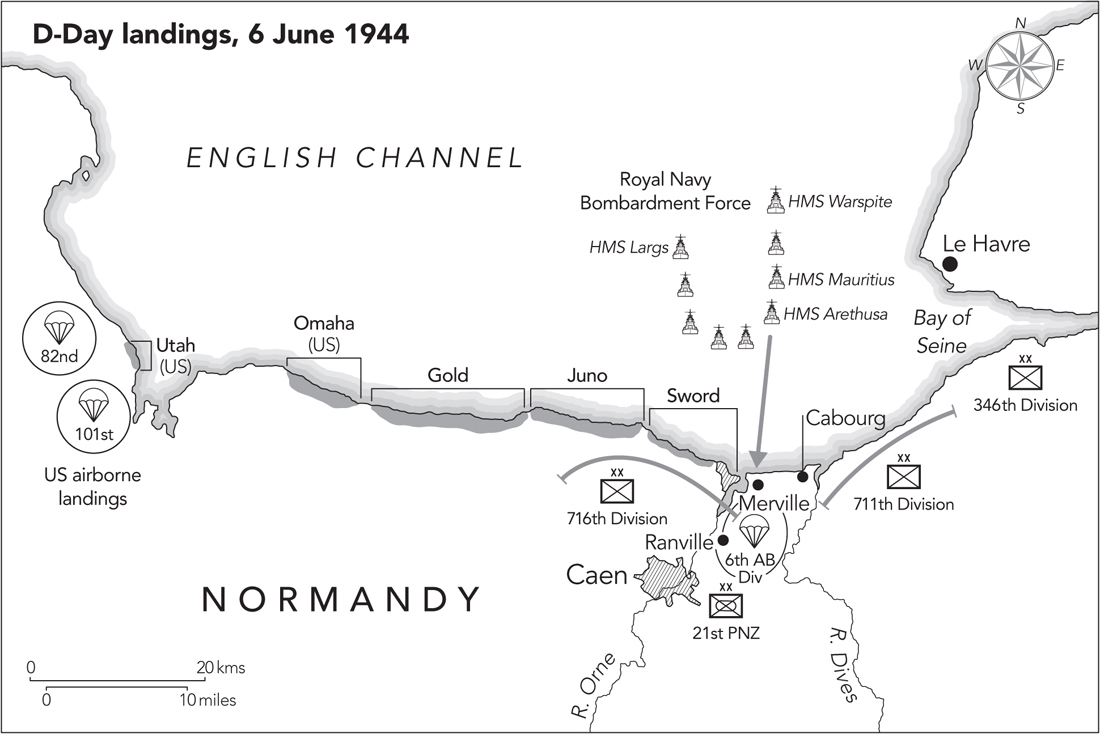

While one of the risks centred on neutralizing the Merville Battery, Ike and Monty agreed with Morgan’s assessment that the risk of counter-attack by German mobile reinforcements into the flanks of the landing also needed to be reduced. But in reviewing Morgan’s plan they felt that his intended invasion frontage of three assaulting divisions in the first wave was too narrow. With Eisenhower’s agreement, Montgomery expanded the length of the invasion area to include the whole of the Cotentin Peninsula. He also increased the number of divisions in the first wave from three to five, landing on five separate beaches instead of three. Two US divisions would land in the western sector along two beaches codenamed Utah and Omaha. One Canadian and two British divisions would land to their east along Juno, Gold and Sword beaches.

The Allies had thirty-seven divisions stationed in England for the invasion, but it would take days and weeks to take them all across the Channel. To Montgomery, success depended on breaching the Atlantic Wall and getting enough troops ashore to consolidate the beachhead before the Germans could bring the combined weight of their panzer divisions against him. Like Rommel, he saw the first hours and days as critical. A successful breakout from Normandy could only come after the Allies had won the race to build up sufficient force ratios ashore to beat off the panzers as they moved to counter the landing.

In line with Morgan’s initial estimate regarding the risk of German attacks into the flanks during the early phases of the operation, the one aspect of the COSSAC planning work that Montgomery did not change was the simultaneous dropping of US and British airborne troops on the eastern and western ends of the invasion beaches. The east flank of Sword Beach where the 3rd British Division would land was a particular concern, given its proximity to the concentration of the majority of German formations around the Seine. Focused on responding to a threat of invasion in the Pas de Calais area, the panzers would come from this direction once the enemy realized that the real threat was in Normandy.

The quickest and most direct approach for German reinforcements moving westwards towards Sword Beach lay across the Dives and Orne rivers, which ran into the sea astride the wooded high ground of the Bréville Ridge. If the German mobile divisions were able to cross these rivers they would have an opportunity to roll up the flank of the invasion from east to west before the Allies had time to land sufficient numbers of their own armoured forces to counter such an attack.

The western side of the ridge, closest to Sword Beach, had the added benefit of the Caen Canal. Fed from the mouth of the Orne, it flowed beside the river along the bottom of the ridge towards Caen. There were only two bridges across the double water feature at the villages of Bénouville on the Orne and over the canal as it passed through Ranville. The bridges were the vital ground and the ridge was the key terrain to defending the left flank of the invasion. Whoever held the bridges would control the most direct access to Sword Beach, and whoever held the Bréville Ridge would have a marked advantage in controlling the high ground that dominated them.

Trying to take the ground from the sea by landing on the beaches to the east of the River Orne would bring the invasion fleet into the effective range of the Germans’ large-calibre naval guns at Le Havre. Consequently, Morgan’s plan to protect the left flank advocated using the British 6th Airborne Division to seize and hold the vital ground and terrain by dropping them behind the Atlantic Wall during the night immediately preceding the arrival of the main seaborne forces on the morning of D-Day. It was a daring and ambitious plan and not without its detractors, particularly among the British Air Staff.

Its leading opponent was Air Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory. Following the catalogue of errors that had occurred during the Sicily landings, the chief air planner in COSSAC had profound misgivings. Leigh-Mallory pointed to the heavy losses of gliders in the Mediterranean and the inaccuracy of the parachute drops where many of the paratroopers had been dropped wide of their drop zones, or DZs. Leigh-Mallory doubted that the fate of airborne forces in Normandy would be any different. In fact he expected it to be worse. The troops landing by parachute and glider would be lightly armed and dispersed, whereas their opponents would be able to concentrate and bring their heavier weapons systems, in terms of tanks and artillery, against them. Given the circumstances, he forecast that the airborne troops would expect to incur 75 per cent casualties.

The more powerful voices of Eisenhower and Montgomery were convinced of the utility of airborne forces and the critical role they had to play in D-Day. Sicily had been the first mass use of Allied glider and parachute troops. While it revealed the need for many improvements, landing airborne troops in advance of the main seaborne force had made a significant contribution to the success of the landing and also convinced Churchill of its possibilities in Normandy. Endorsed at the highest levels, and as a subset of Overlord, the British airborne phase of the invasion would be called Operation Tonga.

Although backing the use of airborne forces, SHAEF’s final adjustment of the plan was one of timing. The shortage of assault landing craft for the invasion meant that the date was put back to 5 June. Delaying by another month allowed more time for the pre-invasion bombings to continue to soften up German defences, and would also align the date of the Allied assault on the beaches with the launch of the Red Army offensive in the east. Additionally, it would provide more time to build up the capability of the airborne forces and improve on the lessons from Sicily. Monty had wanted to increase the number of British airborne troops taking part in the operation, but had been frustrated by the lack of available aircraft to lift them. While the US 82nd and 101st airborne divisions could be lifted in their entirety and dropped on the right flank at the western end of the Cotentin Peninsula, the RAF had insufficient aircraft to fly in all of 6th Airborne Division. With a month’s delay Monty hoped that he might just get the additional aircraft he needed in time.

Two weeks after the photographs of the Merville Battery had been taken, the nominal head of British Airborne Forces was in less optimistic mood as he drove to the headquarters of 6th Airborne Division to give its commander his orders for D-Day. Lieutenant General Frederick ‘Boy’ Browning was a bright young Guards general with a dapper dress sense who had spotted the potential of parachute forces as a brigade commander at the start of the war. His early interest in the development of the airborne arm had led to his rapid promotion, command of the first British Airborne Division and his further promotion as it expanded into a corps-sized capability. But he didn’t feel particularly bright about the message he would have to give to its commander, General Richard Gale.

In terms of appearance, Richard Gale, or ‘Windy’ as he was nick-named, was everything Browning was not. With his regulation military moustache, he had the look of a typical Indian Army ‘Poona’ officer or affable uncle, who would not have seemed out of place in an Evelyn Waugh novel. Although aged forty-three and without a trace of grey in his hair, he looked older and had a portly air about him, not helped by his incongruous style of wearing an open-zipped parachutist’s Denison smock and riding jodhpurs over standard-issue Army boots. He was awarded the MC as an infantry subaltern in the First World War, and might have ended his career as a passed-over lieutenant colonel had it not been for the outbreak of war in 1939. But by 1944, Gale had already worked on airborne staff matters in the plans directorate of the War Office and commanded a parachute brigade. Gale awaited Browning’s arrival with anticipation, eager to discover the role his division would play in the invasion. He was about to be disappointed.

Browning informed Gale that his division would be dropped at the British end of the beaches, around the Bréville Ridge and would then secure the left flank of 3rd Division prior to its landing on Sword Beach. But due to the shortage of lift for his two Para brigades and brigade of glider troops, he was told that he would have to accomplish it by providing only one of his parachute brigades under command to 3rd Division. For a commander who had built up his division from scratch since its formation in April of the previous year it was a bitter blow.

Gale’s single parachute brigade was given three principal tasks. The primary mission was to capture and secure the bridges across the Orne and Caen Canal and destroy the heavily fortified gun battery at Merville. These tasks were to be completed no later than half an hour before daylight on D-Day, prior to the start of the landing of the seaborne forces. The secondary task was to delay the movement of enemy reinforcements westwards by blowing the bridges over the River Dives not more than two hours after the landings, and then by holding key access points across the Bréville Ridge.

It was an ambitious undertaking for one brigade. Composed of 2,200 men formed into three battalion groups, each of approximately 750 soldiers, including supporting arms, such as engineers, signallers and medics, the units would be without the support of heavier conventional forces until the leading elements of 3rd Division landing across the beaches could link up with them. Until that happened, they would have to rely on naval gunfire support to bridge the gap in their limited firepower.

Gale was convinced that what he had been asked to do was beyond the means of one brigade. As he lobbied to be allowed to take his whole division, his staff began to make their plans for the mission with what they had been given. The majority of their planning took place in a heavily guarded farmhouse that had been requisitioned as the intelligence cell of 6th Division’s headquarters. The Old Farm at Brigmerston House was in the village of Milston two miles north of Bulford on the southern edge of Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire. It was ringed with a thick concertina barbed-wire perimeter and a detachment of military policemen; no one got in or out of the building without a specially issued pass.

The precautions taken at the farmhouse reflected the tight ring of security and secrecy regarding all the planning for D-Day. Operation Tonga was no exception. The circle of knowledge beyond COSSAC was kept to an absolute minimum of a few key officers on Gale’s staff and the commander of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, Brigadier James Hill, whose brigade Gale had selected for the mission. The rest of the division were kept deliberately in the dark about what was afoot. But as the war tipped irrevocably against the Germans and the inflow of Anglo-American manpower and materiel began to build up in England from January 1944, most people knew that the second front was coming. But like the Germans on the other side of the Channel, they knew neither when nor where. As the planning continued in the Old Farm at Milston the lives of thousands of men of the 6th Airborne Division were being irrevocably drawn into the events that would unfold on 6 June 1944.

The 6th Airborne Division was one of two battle-ready airborne divisions stationed in England at the beginning of 1944 and had been raised specifically to take part in the invasion. Since its formation, Gale had worked the division hard to declare it ready for operations by the end of the year. It was a major accomplishment and although the division was still to be tested in battle, and regardless of the paucity of aircraft to lift it, the fact that the British could lay claim to having two airborne divisions in their order of battle was an impressive achievement in itself. Four years previously, the very existence of airborne forces was little more than a pipe dream in the minds of a few men and the vision of one man in particular was of seminal significance.