Arbogastes’ continual high-handed treatment of the emperor Valentinian II caused the latter to give him publicly a letter that terminated his command. Arbogastes, however, after having read the letter simply tore up it and stated that Valentinian had not given him his command and therefore could not sack him. Now the rift had become public and could no longer be kept under wraps. Valentinian sent numerous letters to Theodosius in which he complained about Arbogastes’ behaviour and asked Theodosius to help him. Valentinian stated that he would flee to him immediately if the latter would just promise to help him. Theodosius turned a deaf ear to these, but then on 15 May 392 the unthinkable happened. Valentinian was found hanged in his quarters. The desperate Valentinian appears to have committed suicide, but this still aroused suspicions that Arbogastes had had him killed. Arbogastes attempted to prove himself innocent, but to no avail. Theodosius I immediately started to make preparations for war. He was married to Valentinian’s sister and had no other alternative in the circumstances. When it became apparent that there would be no reconciliation, Arbogastes appointed his trusted friend Eugenius as emperor at Lugdunum on 22 August 392. Eugenius was harmless enough to stand as Arbogastes’ figurehead. He was Arbogastes’ client (introduced to him by his uncle Richomeres) who was by profession a teacher of rhetoric who had become a civil servant. Most importantly Eugenius was native Roman and Christian while Arbogastes was a pagan Frank. The new rulers still attempted to court Theodosius and sent two embassies to him, but to no avail. Theodosius temporised because there was still the problem of the ongoing war in Macedonia and Thessaly, but the raising of Honorius to the position of Augustus in January 393 at the latest showed what was to come.

Arbogastes and Eugenius had their own problems. They also needed to secure their own backyard, the Rhine frontier, before they could move on into Italy. Consequently, Eugenius and Arbogastes led their army all the way up to the Rhine frontier in the winter of 392/3 to impress the barbarians with the huge size of their army as a result of which the Franks and Alamanni renewed their treaties.169 I would suggest that in practice this meant that the rulers raised Federate troops from among the barbarians for military service against Theodosius. In April 393 Eugenius and Arbogastes then marched to Italy where they were welcomed with open arms and recognised by the Senate. The pagan Praetorian Prefect Flavianus was particularly enthusiastic in his welcome of the new rulers. Before this the pagans of the Senate had already twice tried in vain to get the Altar of Victory restored back to the Senate because Arbogastes still attempted to reconcile himself with Theodosius, but now that it was clear there would be war, the new rulers were more cooperative. However, since Eugenius also needed to keep the Christians happy he did not officially re-establish the old religion like Julian had done, but restored the Altar out of his own pocket. The new rulers needed to play it on both sides of the fence, but Flavianus went overboard in his enthusiasm of pagan revival with the result that the Christian opponents of the regime could claim with good reason that the new rulers were working for Satan.

In the meantime, in 392 Theodosius had appointed his son-in-law Stilicho as Promotus’ successor. The appointment proved very fortuitous because Stilicho proved himself to be a competent general. The order in which he achieved his successes is not known with certainty, but we know that he managed to finish the wars that had been raging in the Balkans since 388. Stilicho’s first success was against the Bastarnae who had ‘killed’ Promotus. According to Claudian, Stilicho annihilated in a huge slaughter all the Bastarnae globi of cavalry and infantry at Promotus’ tomb. The likeliest date for this campaign is the summer of 392. This operation would have secured the Danube frontier and cut off the barbarian rebels of Thrace from any outside help. Stilicho’s campaign against the Visigoths, Alans, and Huns in Thrace to last from late 392 to the summer of 393. According to Claudian, Stilicho drove the savage Visigoths back to their wagons and then penned within the narrow confines of a single valley all of the barbarians, which consisted of the ‘charging Alans, fierce Nomadic Huns, falx-wielding Geloni (were there still falx-wielding ‘Dacians’ or Scythians from the Don, or is this an antiquarian comment?), Getae (Goths) with bows, and the Sarmatian contarii. All that was left for Stilicho to do was to kill them all, but then the ‘traitor’ Rufinus supposedly convinced Theodosius to grant them a treaty. his was actually a sound decision in the circumstances and symptomatic of Theodosius’ general policy of appeasement. It was better to harness the barbarians under the famous Alaric for useful service against the usurper Arbogastes than to waste valuable manpower in their destruction. The fact that Theodosius was willing to conclude a treaty with the rebels is highly suggestive of his urgent need to collect forces against the usurper. Now both sides could start to make their preparations for war.

According to Zosimus, Theodosius had intended to appoint the very experienced Richomeres as Magister Equitum and supreme commander of the army, but he died of disease in the spring before the campaign could start – or did the emperor poison Richomeres as a precaution because Arbogastes was his nephew? Once again Theodosius recruited large numbers of barbarians from within and without the borders, but the loyalty of the Goths was wavering. When the barbarian leaders were invited to the Emperor’s table in the spring of 393, the drunken Goths quarrelled amongst themselves and the dispute became public. When the emperor had learnt what each of the Goths thought he ended the banquet, after which Fravitta, who had stayed loyal, killed the disloyal Eriulphus (at the instigation of Theodosius?). When Eriulphus’ retinue attempted to kill Fravitta, the imperial bodyguards intervened on his behalf. After this, Theodosius did not intervene when the Goths fought against each other evidently because his side was winning. On 30 December 393 Eugenius and Arbogastes appointed Gildo as Magister Militum per Africam to secure at least his neutrality in the forthcoming conflict (CTh 9.7.9). Theodosius confirmed the decision, because it also suited his goals, but still failed to convince Gildo to support him.

Theodosius began his invasion of Italy in the spring of 394. He appointed Timasius and Stilicho as magistri, and Gainas (Gothic comes), Saul (Alan), and Comes Domesticorum Bacurius (former Prince of Iberia) as commanders of the foederati. The Federates included Goths, Alans, Huns (under their own phylarchoi), Caucasians, Armenians, Arabs, and others. As noted above, thanks to the destruction of the eastern field armies in 376–378 and thanks to the corruption, the regular eastern field army did not possess adequate numbers of high-quality soldiers. It was now absolutely necessary to obtain as many allies and mercenaries as possible to strengthen the army. Regardless, a significant portion of Theodosius’ eastern cavalry consisted of cataphracts in scale or lamellar armour (lamina) under the Dragon banners that must have belonged to the regular army (Claud. II Ruf. 353–365). After all, the cavalry had escaped the disaster at Adrianople almost unscathed. The prophetic services of the hermit John of Lycopolis were once again used to encourage the men. Just at the moment when Theodosius was about to begin his campaign horrible news arrived, his wife and child had died in childbirth. Theodosius could not mourn for more than a day, but one can imagine that he was grief-stricken.

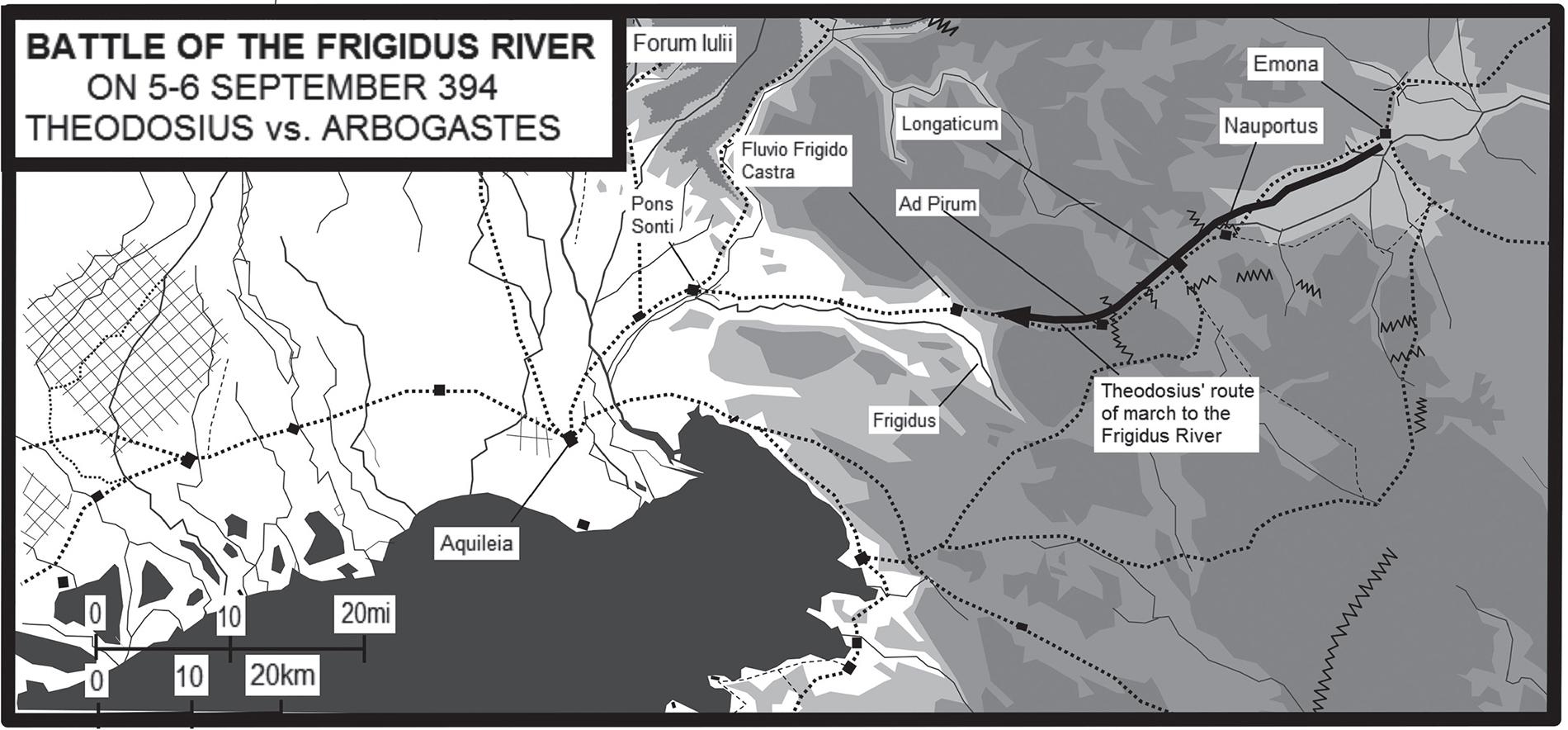

After this, Theodosius marched his army rapidly through the provinces and crossed the Julian Alps (Emona, Nauportus, Longatium, Ad Pirum) with equal speed. This begs the question why Arbogastes had left the fortified passes undefended. The likeliest answer appears to be that Arbogastes had purposely left the route open because he wanted to lure Theodosius to the end of the pass so that he could then ambush and blockade the enemy within the pass itself. Before the arrival of Theodosius, Flavianus performed pagan rites in an effort to raise the morale of the army, but it is uncertain what the effect of this was because the bulk of the usurper’s forces probably consisted of Christians despite what the Christian propagandists claimed. In fact both forces resembled each other in outlook. Both had sizable barbarian contingents fighting alongside the Romans and both armies included men professing different kinds of beliefs and creeds.

Unfortunately, the sources for the Battle of Frigidus on 5–6 September are mutually contradictory even if most of them include the same details, and the following should be seen as just my attempt to make sense out of those. We use the accounts of Eunapius and Zosimus as the base around which other elements are added. Arbogastes’ plan appears to have been to let Theodosius come as far as the plain of Frigidus so that the ambushers that he had placed in hiding in the mountains under Comes Arbitio would take control of the heights and surround and cut off Theodosius’ route of retreat. Theodosius took the bait and advanced to the end of the pass. Arbogastes was by far the better general of the two. In addition Theodosius’ judgment may still have been clouded by his recent personal loss, as well as which he no longer had the able Promotus to advise him.

Arbogastes’ army, consisting of both infantry and cavalry, was fully deployed opposite the mouth of the pass and ready to engage anyone descending into it. Theodosius’ vanguard consisted of barbarians and he ordered Gainas to attack first the infantry phalanx blocking the way followed up by the other barbarian commanders with their cavalry, mounted archers, and infantry. Unsurprisingly the vanguard suffered heavily and was forced to give ground. According to Orosius 10,000 Goths were killed. The barbarians were on the point of breaking when Bacurius launched his attack (Federates with the Scholae and Equites Domestici?) that saved the day. He broke through the enemy ranks and enabled the rest of Theodosius’ army to deploy for combat. It is probable that Bacurius was helped by the ‘eclipse of the sun’ mentioned by Zosimus and Eunapius which we interpret to be the arrival of the storm with the famous Bora wind. The wind threw back the missiles thrown by Arbogastes’ men and dashed and threw their shields about with the result that their shield wall was broken. Contrary to what Christian apologists say this did not decide the battle. Arbogastes’ men were able to regroup and steady the situation, apparently with the help of the reserves and because their ambushers had become visible behind Theodosius’ army. Theodosius had no other alternative than to call off the attack and retreat his men back to the heights.

Arbogastes had won the first day and Eugenius rewarded his men and let them eat. The desperate Theodosius had no alternative but to pray for God. His prayers were answered. It was then that Arbitio’s envoys arrived. He and the other officers promised to betray Arbogastes in return for high positions in the army. Theodosius grasped the opportunity eagerly and gave his promises in writing, and the ambushers duly joined Theodosius’ army. Just before dawn Theodosius’ army repeated their attack and penetrated the enemy camp because the opposing army was still resting. This means that the deserters from the enemy army had also included the guards posted opposite Theodosius. Eugenius was caught and brought before Theodosius and then beheaded. Arbogastes managed to flee to the mountains where he hid for two days before committing suicide rather than be caught. Arbogastes had clearly been the better commander, but this did not help him when his probably Christian military commanders proved disloyal to the pagan Frank.

About 392–4 there happened an event on the Egyptian border which may have changed the balance of power in the area for a while. The Blemmyes were able to defeat the Nubians who had protected the Roman frontier in this area ever since their settlement as foederati by Diocletian. The Blemmyes took over at least five towns and established their capital at Kalabsha – notably the emerald mines were located right next to it. We do not know whether this resulted in hostilities between the Romans and Blemmyes, but this is probable because the Blemmyes became allies of Rome only in about 423. The Romans seem to have left the punishing of the Blemmyes to their Nubian allies. In fact, since the Romans did not conduct any major campaigns against the Blemmyes with their own forces, it is clear that the Blemmyes did not stop the trade with the Aksumites, even if it may have increased the costs of trading along the Nile.