Every year the Quraysh sent out two major caravans, one in the winter and the other in the summer, to biannually balance the lion’s share of their wealth. Besides these two, there were always a number of smaller caravans to raid, but the two major ones, established by Hashim ‛Abd Manef, Muhammad’s great-grandfather, were the greatest prizes to seek. Muhammad, intimately familiar with the trading business, knew the general timings of these caravans. The specific intelligence he regularly received from Makkah gave him more details, thus providing him sufficient information to intercept them. He was informed that a major caravan escorted by seventy horsemen was coming south from Syria under the control of Abu Sufyan bin Harb, one of the important elders of the Quraysh. He knew this in large measure because it was the very same caravan, then traveling north, that he had failed to intercept in the raid to al-‛Ushayrah. By calculating the movement of the caravan, along with the time it took to offload and load goods, the Prophet was able to determine the most opportune time to send out scouts to herald the caravan’s approach.

The caravan coming from Syria was loaded with wealth, having virtually every family among the Quraysh involved even if it offered but minimal profit. It was composed of one thousand camels, and at least one clan, the Makhzum, had upward of ten thousand mithqals of gold carried in the baggage. The total holdings of the caravan were upward of fifty thousand dinars, or five hundred thousand dirhams. A mere threat to this caravan would incite the entire city of Makkah to action, and by plotting to take it, Muhammad was essentially threatening to bring down upon the people of Madinah, the very thing they feared: the full weight of Qurayshi might.

Yet to seize this prize would go beyond the monetary gain, for it would establish Muhammad as the principal leader in the Hijaz. Despite any risks involved, he began his preparations and in doing so realized that he would need more men to ensure success. Therefore, for the first time he tapped the manpower resources of the Ansar. Doing so was somewhat risky because the zakat and other charity of this group provided the base of wealth for the operations of the unemployed Muhajirun. Yet his need for immediate manpower was greater than the need for future tax revenue. It could even be said that he was taking a calculated risk, for if this force were to be destroyed, his days in Madinah would be numbered. Some of the people answered his summons eagerly, but others were very reluctant because they saw this move as an open invitation to all-out war with the Quraysh. It was one thing to launch an occasional small raid on a caravan and quite another to unleash a full-scale operation that could entail serious casualties and invite a strong response from Makkah. Such was a daunting prospect indeed.

Muhammad dispatched a scout to locate the caravan, who was deceived as to the exact location of the caravan by false information given by a native of the area. When the scout returned to the Prophet, the two had a secret consultation in Muhammad’s quarters, whereupon the Prophet came out and called on all who could procure an animal that was ready to ride to accompany him on the raid. Some, eager to now follow up the success of the Nakhlah expedition, asked if they could use their farm animals, but Muhammad refused due to the pressure of time, saying he only wanted “those who have their riding animals ready.”

Having quickly made preparations, Muhammad left Madinah on Saturday 9 December 623, with a force of approximately 83 Muhajirun and 231 Ansar, heading southwest toward the caravan watering location of Badr. He had 70 camels and only 2 horses in his force. Before departing Muhammad personally inspected his men and sent home those he considered too young to fight; the range between 14 and 15 years of age was apparently the break-point. As he looked his men over, the Muhajirun presented a mediocre lot, for they had recently been suffering from disease due to their recent change in venue and diet. Nevertheless, if he was to intercept the caravan he would need every willing man available, regardless of physical condition. Realizing that his advance might be spotted by Qurayshi scouts, not to mention having a sudden premonition of evil regarding a mountain tribe in the area, Muhammad deviated off the main route from Madinah and followed obscure canyons and wadis until he debouched into the open plain of Badr.

Abu Sufyan was aware of the danger. He personally engaged in a reconnaissance of his own, riding well ahead of the slow-moving caravan to reach the wells of Badr just after two of Muhammad’s scouts had left. When he arrived, he asked a local if he had seen anything unusual, and the man told him of two men who came earlier, took some water, and then left. Abu Sufyan went to the place where the men had rested. Spying camel droppings, he broke one open to find a date pit within. “By God, this is the fodder of Yathrib!” His worst fears confirmed, he hastened back to the caravan and ordered it to quicken its pace and deviate to the coastal route, leaving Badr to the east. While this meant they would not get any water, he knew they could proceed without it if necessary, and now was certainly a time of extreme necessity. Concurrently, he ordered a rider to rush to Makkah and alert the town that the caravan was in jeopardy.

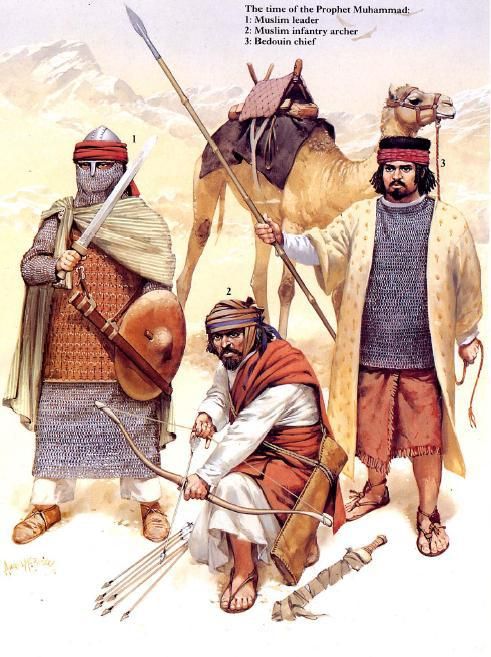

When this messenger arrived, having torn his shirt and cut the nose of his camel in grief, he cried “Oh, Quraysh, the transport camels, the transport camels! Muhammad and his companions are lying in wait for your property with Abu Sufyan. . . . Help! Help!” With this warning ringing in their ears, the leaders of Makkah rapidly prepared a relief column of 1,000 men. About 100 were mounted and armored, with about 500 of the remaining infantry in chain mail as well. The clan of Makhzum, with so much to lose, contributed 180 men and one-third of the cavalry dispatched. The Quraysh lightheartedly declared as they made their preparations that Muhammad would not find this caravan such an easy prey as the one at Nakhlah. With Abu Sufyan leading the caravan south, another of their key leaders, Amr bin Hisham, known to the Muslims as Abu Jahl, was in command of the relief effort. Before leaving, the leaders in Makkah took hold of the curtains of the ka‛bah, crying out “O Allah! Give victory to the exalted among the two armies, the most honored among the two groups, and the most righteous among the two tribes.” Twelve wealthy men of the Quraysh also determined to provide the necessary meat on the hoof for the journey, each supplying ten camels to be slaughtered for rations. Logistical lift was provided by seven hundred camels for this hastily organized force.

Having prepared the relief force as speedily as possible, they marched hard to the north, soon meeting another messenger from Abu Sufyan declaring the caravan was now safely past the danger zone. But Abu Jahl was determined to press on ahead and thus changed the mission of protecting the caravan to one of engaging Muhammad’s men. This caused Abu Sufyan to cry in anguish, “Woe to the people! This is the action of Amr bin Hisham,” thereby exonerating himself of Abu Jahl’s actions. It was possible that Abu Jahl was determined to gain glory for himself at the expense of Abu Sufyan and thus gain power in Makkah, since the two were intense rivals. However, it should also be noted that Abu Jahl probably had a far better appreciation of the danger presented by Muhammad’s insurgency, and was thus willing to risk more in an effort to crush it.

Abu Jahl’s rash decision to change the relief column’s mission led to immediate complications. With a pending, though now seemingly unnecessary, battle in sight, a number of the Quraysh were not interested in either fighting their fellow clansmen or helping him establish primacy in Makkah due to a renowned victory. This was further exacerbated by the dream of one of the members of the al-Muttalib family, the very same from which Muhammad hailed, in which he foresaw the deaths of the principle nobles of the Quraysh in the coming battle. Abu Jahl could only lament with disdain that “this is yet another prophet from the clan of al-Muttalib,” and urged his men to ignore the portent. Relating such a dream could very well have been the action of a fifth columnist within the ranks of the Quraysh to instill fear and doubt, thus dampening their courage. Of the one thousand who started out, anywhere from two hundred to four hundred withdrew and headed back to Makkah, and those who did remain were still unsure about the situation. With divided counsel and with overconfident leaders, the Qurayshi force pressed northward to the probable spot of Muhammad’s force near Badr. They were so sure of victory that they even turned down offers of reinforcements from a nearby tribe.

The area around Badr is essentially a bowl with mountains or ridges surrounding it on nearly every side. However, to the northwest and northeast there are passes, and to the south the terrain levels out to allow a caravan trail to pass through. It is about 1.6 miles wide from east to west and 2.5 miles long north to south. Those within the plain would be hidden from view until a force moved over the ridges or up the caravan trail. Due to its wells, there was also a grove of trees on the south side of the plain that could make spotting an enemy force more difficult from the southern approach.

Having sent men to collect water at Badr, and those men not having returned, Abu Jahl realized where Muhammad’s men probably were, though he would be unable to easily hear their movements because the Prophet had ordered the bells cut from the necks of his camels. However, this mattered little as Abu Jahl’s scouts confirmed his suspicions regarding the Muslims’ location. Meanwhile, Muhammad was completely oblivious to the onrushing relief force until the day before contact, when his men captured the Qurayshi water bearers. After trying to beat the truth out of them, and disbelieving it when they heard it, Muhammad admonished his men that these were indeed water bearers from a large relief force from Makkah. When the water bearers told the Prophet that the force killed nine to ten camels per day for food, Muhammad reckoned that the force was a thousand strong, which was an accurate assessment, though not taking into account those who had broken ranks and went back to Makkah. Muhammad, caught by surprise, now realized he was in serious trouble. With his men on foot, faced with what he thought was a thousand men, many of them on horseback, he would be hard-pressed to withdraw into the mountains. With this in mind, and his need for some type of substantial victory, he was forced to make a stand, risking everything on one desperate engagement.

He now needed to inspire his men, for they had come out to raid a caravan, not to fight a pitched battle. He had pinned his hopes on the Ansar, and to them he turned for a declaration of loyalty. Securing this, he prepared for the first major fight of his life. Riding ahead of his men on his camel, he surveyed the plain to determine what to do. One of his officers, al-Hubib bin al-Mundhir, asked him if Allah had ordered them to fight a certain way or if this was just a matter of military tactics. When Muhammad said it was the latter, the officer advised that the wells of Badr to the west and south should be stopped up with rocks, and a cistern should be constructed to the east to hold plenty of water for the Muslims. Muhammad adopted the plan at once, and work teams quickly completed the projects.

There is room for debate as to where Muhammad actually positioned his men. While tradition has determined that he positioned himself almost to the center of the Badr plain, the early documentation and common sense would indicate that he positioned the men further to the northeast, with their backs to the mountains and with his own headquarters on the slopes of the mountains overlooking the ground below. This placed his men close to their cistern and provided him a place to observe the action with a ready means to escape if the battle went poorly. In doing this, Muhammad placed his men on what Sun Tzu called “death ground.” With no room to maneuver they were compelled to fight and win, or die trying. However, Muhammad did have the foresight to position them in such a way that scattered survivors would be able to flee into the mountains if they fared badly in the fight, a concept reasonably well known to some military thinkers of that day.

On the morning of 22 December 623, or 17 Ramadan AH 2, Abu Jahl’s force stopped short of the slopes to the south of the Badr Plain and encamped. He sent a scout ahead to estimate the situation, and when he returned it was with grim news. He accurately reported the Muslim strength but then noted that they were prepared to fight to the death, and this would incur heavy casualties in the Qurayshi force. “I do not think a man of them will be slain till he slay one of you, and if they kill of you a number equal to their own, what is the good of living after that? Consider, then, what you will do.” With these words, dissension surfaced in the ranks of Abu Jahl’s force, and he with difficulty put down the tide of division that could further weaken his force. As Abu Jahl struggled to control his wavering leaders and warriors, Muhammad moved about the ground near the Badr wells, placing his hand on the sand to declare that certain men of the Quraysh would die at such a point. The differences between the two camps on the eve of battle were striking.

During the night, a light rain fell and the area where the Quraysh had encamped was in the wash of a wide wadi, thus becoming waterlogged. Meanwhile, the Muslims sheltered beneath their shields as Muhammad busied himself with prayer. When the Friday morning of 23 December came, as the Muslims wearily gathered for prayer with the breaking dawn, the Quraysh found that their horsemen would have difficulty with the loose terrain, forcing many to dismount. Only the key leaders such as Abu Jahl remained mounted. To make matters worse, there was further division within the Qurayshi camp. That night Abu Jahl had already rejected reinforcements offered by a neighboring tribe, apparently determined not to share in the glory of his anticipated victory, when he had an argument with fellow noble Utbah bin Rabi‛ah. Utbah had been counseling the nobles that they should not engage in battle, and Abu Jahl chided him for his defeatism. “Your lungs are inflated with fear,” he noted, to which Utbah retorted that his courage would be displayed on the field of battle. To emphasize his determination to attack Muhammad in the morning, Abu Jahl unsheathed his sword and slapped the back of his horse with the flat of the blade. Another, watching this exchange, left in bewilderment, noting that such discord among the leaders was a bad omen.

As dawn broke, both sides began to make their preparations in what was to become an unusually hot day. Even as the Quraysh were lining up, Utbah bin Rabi‛ah rode on his red camel among the men, exhorting them not to fight against their family members, a fact very personal to him since one of his own sons had become a Muslim. “Do you not see them,” referring to the Muslims, “how they crouch down on their mounts, keeping firmly in place, licking their lips like serpents?” Utbah’s openly displayed dissension put Abu Jahl into a fit of fury, declaring that if “it were anyone else saying this, I would bite him!” Attempting to again rally his men, Abu Jahl cried out to Allah, asking him to destroy the army that was unrighteous in his sight. With the advantage of their cavalry lost due to the soft ground, and lacking substantial water and already suffering from thirst, Abu Jahl moved his hesitant fighters over the ridge and onward to destiny in the Badr plain.

Even as he did so, Muhammad had completed arranging his men during the predawn hours with only a few clad in light chain mail for battle. He personally used an arrow to align them by ranks into a straight line, even jabbing one of his men, Sawad bin Ghaziyyah, in the stomach with the arrow tip to get him in line. Sawad declared that the Prophet had injured him and demanded recompense on the spot. Muhammad uncovered his torso and told him to take it. Instead, the warrior leaned forward and kissed the Prophet on the stomach. When Muhammad asked him why he did this, Sawad said that he might very well be killed and wished that this be his last remembrance of his leader. Having positioned his men, Muhammad returned to the small tent set up as his headquarters and demonstrated his confidence by taking a brief nap. He placed Qays bin Abu Sa‛sa‛a in command of the rear guard, composed of older men and probably armed with spears, while to the front Sa‛d bin Khaythama was in command of the right and al-Miqdad bin al-Aswad in charge of the left. These two were leading the younger men, ardent and spoiling for the fight. The latter commander was possibly the only Muslim actually on the battlefield mounted on horseback. Several gusts of wind blew across the sand, and Muhammad cried out that the angels of Allah had arrived, so each man should mark his own hood and cap with a special symbol of identification to protect them from angelic wrath.

As the Qurayshi force advanced slowly across the plain, several men stepped forward to initiate single combat. Two Muslims were killed in the first exchange, along with one of the Quraysh who had vowed to fight his way through to the Muslim water supply. He was met by Muhammad’s uncle Hamzah, who slashed off part of one leg before the man managed to reach the water. Hamzah climbed into the pool and finished the Qurayshi warrior off with a single blow. With these modest preliminaries complete, the champions came forward to do single combat. Honor and shame being a key virtue for such tribal cultures, three men from the princely class of the Quraysh, Utbah bin Rabi‛ah along with one of his sons and Utbah’s brother, demanded to have combat with men of equal social stature. Three dutifully stepped forward, including Muhammad’s uncle Hamzah, his cousin ‛Ali bin Abu Talib, and Ubaydah bin al-Harith. When the duel was over, the three Quraysh were dead and Ubaydah was mortally wounded when his leg was severed by the blow of a sword from Utbah’s brother. As for Utbah bin Rabi‛ah, he died displaying the very valor he had declared the night prior to Abu Jahl.

With the single combats essentially inconclusive, the moment for battle had arrived. Even as the sun began to cap the mountains to the southeast, Abu Jahl’s men found the light blazing at an angle into their eyes, and they squinted to the northeast to see the Muslims remaining rock solid in their ranks. The lines of the Quraysh now began to advance.

The Muslims remained stationary, the sound of mailed warriors steadily approaching their line. In the midst of the Qurayshi force they could see three battle flags of the ‛Abd al-Dar, and several mounted men leading them on, their mail gleaming in the morning sun. Abu Jahl, on horseback, continued to urge his men forward, still sensing an unease and hesitance in their gait. “One should not kill the Muslims,” he cried. “Instead, capture them so they can be chastised!” Ahead he could see the four battle flags of the Muslims, with the larger one in the center and elevated to the rear—the green flag of Muhammad himself. Abu Jahl felt his ardor rise, and he cried out poetic verse about how his destiny was to wage war and conquer his foes. Abu Jahl must have at this moment sensed that his desire for triumph was about to be fulfilled.

As for Muhammad, he had informed his men that anyone who killed any of the enemy would get that man’s armor and weapons as plunder.78 He watched the scene unfold below, a cloud of dust now rising from the ranks of the advancing enemy. Muhammad had ordered his men to keep the enemy at bay with missiles, only resorting to sword play at the last minute. Commands were now shouted out and several volleys of arrows were thrown from Muslim archers posted to the right and left of the main body. This was followed by a shower of stones from the main body of the Muslim force. The arrows and stones, though mostly harmless against the armor and shields of the enemy, still served as a harbinger of the fight to come. The Muslims, being less armored, probably suffered more in the exchange, with at least one killed as far back as the cistern as he took a drink of water. Following the missile skirmishing, the signal was given and the Muslims now began their own slow advance, marching in ranks toward their enemy. Then came the command to draw swords, and in unison the front rank unsheathed their curved Indian blades, a flash of brilliance like lightning dashing into the eyes of the Qurayshi soldiers, even as the rank behind leveled their spears.

And then Muhammad gave the signal to charge. The Muslims suddenly cried out at the top of their lungs, shouting “One! One!” a sound like thunder echoing from the mountain sides as they broke ranks and bolted for the center of the Qurayshi lines. As swords were wielded and spears thrust, the Qurayshi men began to feel the exhaustion already creeping over them as they cried out for the water they did not possess but now so desperately needed. In contrast, individual Muslims could fight for several minutes and then quickly pull from the ranks to refresh themselves in their trough before returning back to the fight, their gap filled by men in ranks behind them. One of them, ‛Awf bin al-Harith, while taking a respite from the fighting asked the Prophet what makes Allah laugh with joy. Muhammad replied that it was the man who charged “into the enemy without mail.” On hearing this, ‛Awf stripped off his chain mail and tossed it aside. He then threw himself into the ranks of the Quraysh until he was killed.

Because of their armor, few of the Quraysh fell in the first charge, but their morale was wavering even as Muhammad paced back and forth under his tent, declaring that the Quraysh would “be routed and will turn and flee. Nay, but the Hour (of doom) is their appointed tryst, and the Hour will be more wretched and more bitter (than this earthly failure).” The Muslims purposely targeted the leaders of the enemy, and Abu Jahl’s horse was quickly brought down. No longer seeing their leader hovering over them, the Qurayshi line shuddered and then broke in confusion as men, overcome by thirst, exhaustion, and doubt, turned to run. It was then that the real killing and maiming began, as the Muslims raced after them, swords flashing as they dismembered bodies and took heads. Even then, individual men, usually noblemen of the Quraysh, attempted to make a stand and rally their fleeing men until they were cut down.

Abu Jahl, finding himself cut off from his army along with his son Ikrimah, positioned himself with his back to a thicket of scrub, fighting until he was severely wounded. Mu‛adh bin Amr cornered him, his sword severing a leg and sending the foot and calf flying. Ikrimah desperately fought to protect his father and brought his sword down on Mu’adh’s shoulder, nearly severing the man’s arm. Mu’adh staggered from the fight, and, with his father too injured to move, Ikrimah withdrew as well, leaving his father to his fate. Another Muslim passed by and gave Abu Jahl an additional blow, though still not fatal.85 As for Mu’adh, he would rest and reenter the fight, soon after tearing off his mangled arm because he was dragging it around. Despite the severity of his wound, he would survive the battle and live into the days of the khalifate of ‛Uthman.

With the Quraysh in full flight, Muhammad’s men began to round up prisoners, a sight that angered one of the leading Ansar, Sa‛d bin Mu‛adh, who was now with the Prophet at his command tent. Muhammad could see the displeasure on the man’s face and asked him why he disapproved taking prisoners. “This was the first defeat inflicted by God on the polytheists,” Sa‛d remarked. “Killing the prisoners would have been more pleasing to me than sparing them.” Despite Sa‛d’s attitude, the Muslims continued to assemble the prisoners, sorting through the dead and wounded to find friends or enemies and take stock of their incredible victory.

‛Abdullah bin Mas‛ud found Abu Jahl still alive and barely breathing from the wounds he had received. He placed his foot on his neck and asked, “Are you Abu Jahl?” Upon affirmation, he took hold of his beard and severed the dying man’s head. He then took it and threw it at Muhammad’s feet, who gave thanks to Allah for the great victory. The dead Quraysh, a total of at least fifty and possibly as many as seventy, were thrown into one of the wells, with Muhammad reciting over them, “have you found what God threatened is true? For I have found that what my Lord promised me is true.” At least forty-three prisoners were taken, though some sources say as many as seventy were captured. As for the Muslim dead, Ibn Ishaq states that only eight died at Badr, although other sources placed the number as high as fourteen. Among the dead of the Quraysh were a disproportionately high number of nobles, and the loss of their core leaders had to be a serious blow to them. Many had stayed and died fighting, even as their servants and lower ranks fled. In addition, if the Quraysh had about seven hundred men on the field and suffered seventy dead, 10 percent were killed, a rate comparable or significantly higher in light of other battles not only ancient but even from the modern era.

While it is tempting to attribute the Muslim victory at Badr to the power of Allah or to angelic intervention, just as Muslim writers would contend, there were conventional reasons why they won. The Quraysh were divided among themselves, uncertain as to the wisdom of their leader’s actions and concerned about fighting their brethren from their clans. In contrast, the Muslims were actuated and motivated by one force: the will of their leader Muhammad. The weather also worked against the Quraysh, robbing them of the one element that could have proven decisive in battle, their cavalry. The Muslims were on the defensive, fully rested and provisioned, while the Quraysh lacked that vital necessity of water so crucial in the desert. This was accentuated by the fact that the Muslims were more lightly armored than the Quraysh, and thus more mobile and resilient in an infantry battle waged in the desert, which could still become sufficiently warm in December. Muhammad had also chosen the terrain carefully, following counsel and wisdom of those more experienced in the actual tactics of battle, while Abu Jahl scorned the advice brought to him by other noblemen of the Quraysh. The latter also allowed his army to be drawn into battle on ground not of his choosing. Finally, the Quraysh had underestimated Muhammad’s capabilities while the prophet had overestimated theirs. The former approached the battle overconfident of an easy victory while the latter prepared to fight to the death, certain that he and his men would either immerge triumphant or his movement would be destroyed forever. Prepared to die, Muhammad’s men triumphed, a factor that had brought victory to many combatants throughout history.