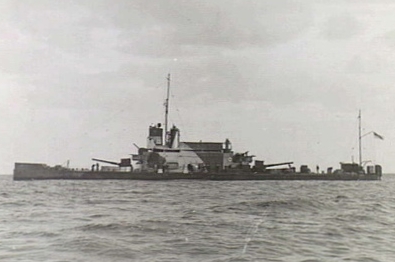

Ladybird off Bardia on 31 December 1940

Ladybird’s gunners in action during the bombardment of Bardia, 31 December 1940

Following the Sidi Barrani débâcle, Marshal Graziani had complained bitterly that he was being compelled to wage ‘the war of the flea against the elephant’, recommending that the army should be withdrawn as far west as Tripoli. Since this meant abandoning the entire province of Cyrenaica, Mussolini thought that he had lost his mind. However, the loss in succession of Bardia and Tobruk placed a different complexion on the matter. After making a brief stand along the line of the Wadi Derna, the Italians did decide to retire into Tripolitania, using the coastal route through Benghazi. Alerted as to what was happening, O’Connor despatched the 7th Armoured Division across the base of the Benghazi Bulge while the 6th Australian Division pursued the retreating enemy along the coast. On 5 February the Italian Tenth Army suddenly found itself trapped between the two at Beda Fomm. During repeated attempts to break through, its commander, General Tellera, was mortally wounded. Following the failure of his last attack on the morning of 7 February his successor, General Bergonzoli, surrendered. Over 25,000 prisoners were taken, as well as over 100 tanks, 216 guns and 1500 wheeled vehicles.

In addition to their bombardment duties, the Insects had been kept extremely busy throughout the campaign. Their shallow draught enabled them to act as supply carriers, and at one time they were delivering 100 tons of urgently needed drinking water daily to the army. They also brought reinforcements forward and ferried hundreds of tractable prisoners back to Mersa Matruh on their decks.

Only a single Italian division and fugitives from vanished formations lay between O’Connor and Tripoli. The probability is that if the advance had continued Tripoli would have been taken and the Desert War would have ended there and then. That, however, is hindsight. At the time, Churchill decided that once the threat to Egypt had been decisively dealt with, Wavell should send troops to Greece to assist in the defence of that country, leaving a screening force in Cyrenaica to guard against an Italian revival. Unfortunately, the campaign in Greece ended in defeat, as did the subsequent defence of Crete, and the Royal Navy was required to pay a high price in lost or damaged ships during the subsequent evacuations.

The second consequence of the British victory in Africa was that Hitler was forced to provide support for his tottering Italian ally, who from that point became the junior partner in the Axis alliance and something of a liability. While Italian reinforcements and German armoured units were hastily shipped into Tripoli, the Luftwaffe quickly made its presence felt. In command of the German element of the new Axis army in Libya was the then Lieutenant General Erwin Rommel. It quickly became apparent that while he was nominally subordinate to the Italians, in practice it would be he who made the going. On 31 March he opened his first offensive, cutting across the base of the Benghazi Bulge and provoking a hasty British withdrawal. He failed to capture Tobruk but entered Bardia unopposed and secured the Halfaya Pass and Solium escarpment crossings on the Egyptian frontier.

Having been assured by Cunningham that Tobruk could be supplied by sea, Wavell decided that it would be held, thereby depriving Rommel of the deep-water port he needed to ease the strain on his long supply line. Initially the garrison would consist of Major-General Leslie Morshead’s 9th Australian Division, supported by British artillery and armour. Unable to make any impression on the defences, Rommel was forced to spend the rest of the year maintaining a regular siege, simultaneously fending off British attempts to relieve the fortress. Two such attempts, the first in May and the second in June, resulted in failure and Wavell being replaced by General Sir Claude Auchinleck as Commander-in-Chief Middle East.

The Inshore Squadron had not escaped unscathed during these events. The Luftwaffe’s Ju 87 dive bombers, the legendary Stukas, were especially troublesome. Whereas the Italians had preferred to area bomb from high altitude, the Stukas bored straight down on their targets like black-crossed pterodactyls, sirens howling and bombs screaming. To anyone beneath a Ju 87’s attack-dive it seemed as though he had become the pilot’s personal target and until one got used to it the experience was very frightening. The Stukas were, of course, very vulnerable to fighter attack, but for the moment the British had few fighters to deploy and their only worry was the volume of anti-aircraft fire that could be directed at them. As the principal target of the German dive bomber squadrons during this period, the Royal Navy quickly developed a grudging respect for their professionalism and courage. At Benghazi Terror was narrowly missed by a bomb on 22 February, the damage being such that several of her compartments were flooded. This was compounded when, on her way back to Tobruk, she struck two mines. She was then subjected to further air attacks, the combined effect of which was to break her back. On 25 February her captain took the decision to abandon her and two hours later she rolled over and sank.

Naturally, the dive bombers were drawn to the increased maritime activity centred on Tobruk, which Rommel mistakenly believed was an evacuation rather than a reinforcement of the garrison. On 10 April Ladybird slid into the harbour, having taken part in an abortive attempt to secure the island of Castelorizo, off the Turkish coast, as a motor torpedo boat base. Castelorizo, it should be mentioned, was part of the Dodecanese group, which Italy had also won from the Ottoman Empire in 1912, and lay within comfortable striking distance of Rhodes, the principal island in the group. The operation was badly planned, although Ladybird had nothing with which to reproach herself. After the initial landings, the Italian defenders had retired to a fort on a hill above the town. This Blackburn turned into a ruin with a dozen well-placed 6-inch shells, so that when the landing force closed in, the defenders streamed out with their hands raised. Now short of fuel, the gunboat set off for Cyprus and at this point the enemy on Rhodes began to react. Ladybird was subjected to a series of air attacks, and although her triple rudders gave her the ability to twist and turn unpredictably, she was hit by a small bomb which wounded all the forward 3-inch gun crew. Drawing as little water as she did, she began to roll wildly as bombs churned up the sea all round her. Evidently satisfied, the airmen departed; to his surprise, Blackburn learned later that the Italian radio had reported his ship as being sunk. Meanwhile, the enemy had further reacted by landing fresh troops of his own on Castelorizo, and as the British landing force lacked heavy weapons it was agreed that it should be taken off. Disappointing as the Castelorizo operation was, several valuable lessons were learned, among which was that the poor performance of the Italians in North Africa could not be taken for granted everywhere.

On her return to Alexandria, Ladybird, accompanied by Gnat, was sent through the Suez Canal into the Red Sea, where an Italian destroyer flotilla based at Massawa was thought to be on the point of interdicting the route between Suez and Aden. In the event, the threat did not materialise and, after undergoing a brief refit at Port Said, Ladybird sailed west to Tobruk.

While the Luftwaffe’s intervention had originally been made from bases in Sicily, Rommel had recovered so much territory that it was now operating from airfields in Cyrenaica. The Stuka squadrons menacing Tobruk harbour were based at Tmimi, supported by more bombers and fighter escorts at Gazala and Derna, all a comparatively few minutes’ flying time to the west. The harbour was also within range of the German heavy artillery, so for her own protection Ladybird took up her berth in the lee of the sunken freighter Serenitas. On the night of 14/15 April the purpose of her presence became apparent. Blackburn took her out into the darkness and sailed west until she reached a position off Gazala. She proceeded to pound the airfields savagely, her shells exploding among parked aircraft, bomb dumps, barracks and a tank leaguer in which several vehicles were set ablaze. Satisfied with the night’s work, Blackburn withdrew into his lair. Every few nights Ladybird repeated the treatment, her attack on 28 April being particularly successful in that a large concentration of enemy transport vehicles, the very lifeblood of desert warfare, was left wrecked and burning. Elsewhere, she used her guns in support of sorties made by Morshead’s belligerent Australian garrison.

Naturally, the Luftwaffe did not take kindly to all this. It was fairly obvious that the source of their troubles lay somewhere in Tobruk harbour, against which they mounted a heavy raid during the afternoon of 7 May. Mistakenly, the Stukas took the fleet minesweeper Stoke as their target. She sank after being hit repeatedly, her survivors being rescued by the Ladybird’s crew. Stoke’s captain has left a vivid account of the attack:

All knew that under existing conditions in the harbour and with no fighter protection and the enemy aircraft doing as they liked it was only a matter of time before a ship was hit, but there were no complaints. Guns’ crews stuck to their weapons until either they were blown away or there were no aircraft left to shoot at.

If the German airmen thought they had solved their problem they were mistaken, for on the night of 11/12 May Ladybird was back battering their airstrips. It was, therefore, in a vengeful spirit that a total of 47 Ju 87s and Ju 88s returned to the attack at about 15:15 the following afternoon. With a quiet efficiency born of familiarity the Ladybird’s crew went to action stations, manning her anti-aircraft armament. This included the 3-inch guns, the 2-pounder pom-pom, and Lewis light machine guns, supplemented by captured Italian weapons including a 20mm Breda cannon and two 8mm Fiat machine guns.

Three Stukas led the attack on the gunboat, howling down through the tracer that snaked up to meet them. One bomb from the first plane burst on the pom-pom mounting, destroying the weapon and killing its crew. Shards of flying metal cut down the two Fiat gunners. Almost simultaneously a second bomb penetrated the boiler room and exploded within, blowing out the sides of the hull. Ladybird, mortally hurt and afire aft, began to settle by the stern with a list to starboard.

The second explosion had flung the Breda crew off their feet. Led by CPO Albert Thornton-Allen, who had already been awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for the probable destruction of two Italian aircraft during the Castelorizo affair, the semi-stunned men quickly got their weapon back into action. All round them every one of the ship’s remaining anti-aircraft weapons was hammering away at the attackers. One of the Stukas, its pilot shot dead at his controls, failed to pull out of its dive and plunged into the harbour; another, trailing smoke and flames, disappeared behind the town to explode in a fireball in the desert beyond.

Lieutenant Diack, the ship’s first lieutenant, gave Blackburn his damage control report. The fire was approaching the after magazine, which could not be flooded because the valves could no longer be reached; it was impossible to raise steam; the ship’s back was all but broken and she was continuing to settle. Blackburn gave orders that the wounded should be taken off in the motor sampan and waited with the rest of his crew for the boats which were already approaching the stricken vessel.

The fire spread throughout the ship, sending up a dense cloud of black smoke until she settled into the mud on an even keel in just ten feet of water. The White Ensign continued to fly from her broken foremast for the remainder of the siege as though the fighting Ladybird refused to die. Nor did she. Her 3-inch gun remained above water and, having been returned to working order by the Royal Artillery, was manned by them during subsequent air raids.

The Ladybird had been a ship with her own personality and a strong esprit de corps among her crew. As she was well known to the Mediterranean Fleet and the army, her loss was a matter of great sadness. General Morshead, by no means the most sentimental of men, sent Blackburn a sympathetic note. Admiral Cunningham received the following message from the commanding officer of the South Staffordshire Regiment:

All ranks of South Staffords having had opportunity of getting to know officers and crew of HMS Ladybird and seeing so much of their co-operation in the Western Desert, wish to express their sympathy at the loss of this gallant little ship.

Cunningham himself had something of a soft spot for Ladybird:

The Ladybird’s sailors were intensely proud of their ship and her record. I visited some of her wounded in hospital and was greatly struck by their cheerfulness. Two young men in adjacent beds with only one leg between them made a very deep impression on me. They took their disability in such a fine spirit.

Aphis and Gnat had meanwhile been active in the Gulf of Sollum. On 12 April, as Rommel’s advance units began consolidating their positions on the Egyptian frontier, Campbell received orders to investigate how matters lay in Bardia. Once more the Aphis penetrated the harbour in darkness and Campbell had himself rowed to the wooden jetty on its north shore. He had barely set foot upon it when he heard voices nearby, talking in German. The port was clearly in enemy hands and he quietly retraced his steps to the boat. So absorbed were the sentries in their conversation that neither its departure, nor that of the Aphis herself, attracted their interest.

Both gunboats duelled regularly with enemy artillery in the Sollum/Halfaya Pass area. On one occasion Gnat sustained minor damage but wiped out the offending battery in return. Having completed repairs, she replaced Ladybird at Tobruk and on the night of 14 May eliminated a heavy battery that had been bombarding the port area. Captain Poland, now commanding the Inshore Squadron, suggested that Davenport should strike his topmast to make her less conspicuous, and this was done. He also directed the gunboat to berth in a small creek which was eventually named Gnat’s Cove. There, during the day, she sweated out the North African summer beneath camouflage nets, emerging at night to make the enemy’s life as much a misery as had Ladybird. By now, Cricket, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Edwin Carnduff, had also reached Port Said from the Far East. After a long and difficult passage she required a refit but had to wait her turn while the dockyard dealt with larger warships damaged during the fighting off Greece and Crete. At length the work was completed and in June 1941 she received her first assignment, which was to join the sloop Flamingo and the whaler Southern Isle in escorting a small convoy bound for Tobruk.

At this stage almost anything that could float was being used to supply the embattled fortress. The convoy consisted of two small and very elderly Greek coasters, one of which was 50 years old and could only slop along at 4½ knots, thereby reducing the speed of the rest to a snail’s pace. Air cover was provided by British and South African fighters but as the ships approached Tobruk during the afternoon of 30 June, these became involved in dogfights with enemy fighters escorting waves of dive bombers.

Carnduff successfully avoided damage during the first three attacks by waiting until he saw the bombs leave the aircraft and then jamming his triple rudders hard over, leaving the bombs to explode in the spot where she would have been. When the fourth German attack came in, however, the enemy had clearly decided to limit his options. While a Stuka approached from abeam, a Ju 88 came in from ahead. Carnduff delayed his helm order until the last possible minute, causing the Stuka to miss, but the Ju 88’s 1000-pound bomb fell close alongside. The gunboat staggered under the impact of the explosion. Her decks were swamped with cascading water which flooded the engine and boiler rooms, wrecking the dynamo. Several men sustained leg and ankle injuries from the transmitted Shockwave. Worst of all, the ship’s frame was buckled, her bottom plating was distorted into metallic ripples, her machinery was damaged, she was making water and was down by the stern. While Flamingo escorted the convoy into Tobruk, Southern Isle stood by the crippled Cricket until nightfall and then towed her back to Mersa Matruh. The gunboat had fought her last fight.

Aphis relieved Gnat at Tobruk, continuing the work of battering the enemy’s airfields and heavy artillery. The months of August, September and October were taken up with the relief by sea of the 9th Australian Division with the British 70th Division. During the early hours of 21 October, Gnat, having rejoined the fray after a rest period, was escorting several ‘A’ lighters – motorised landing barges – on their return journey from Tobruk, when she was torpedoed by U.79. The explosion blew off her bows, threw up such a column of water that she was all but swamped and flung on to her beam ends, and started fires. Slowly she righted herself but remained with a list to starboard and down by the head. While the crew were tackling fires and shoring up bulkheads, two more torpedoes were fired. One missed. The other, though running true, simply grazed its way under the gunboat’s after part without exploding; imagining that he was dealing with a conventional warship, the U-boat captain had failed to allow for the fact that the gunboat’s stern was drawing even less water than before.

The immediate danger past, Davenport was able to go slow ahead for a while in the hope that the shored bulkhead would hold. Gradually, however, with her deck awash, settling slowly by the head and steerage way lost, he was compelled to shut down the boilers. Help arrived in response to his report of the incident and the gunboat was taken in tow stern-first by the destroyer Griffin. Even so, as the sea rose during the night, it was considered unlikely she would survive. The crew were taken off but at dawn Gnat was still afloat, albeit with her rudders now clear of the water. The tow continued at four knots through a moderating sea until, west of Mersa Matruh, the naval tug St Monance appeared. Davenport and eleven of his men returned to the ship to transfer the tow from the Griffin. At 13:00 on 22 October, over 30 hours after the torpedo had struck, Gnat entered Alexandria to receive Admiral Cunningham’s congratulations on a fine piece of seamanship. Some consideration was given to welding the undamaged bow of the Cricket to the Gnat’s still serviceable afterpart; that, after all, had happened in World War I to the similarly damaged destroyers Zulu and Nubian, thereby creating a new destroyer, the Zubian. Unfortunately, such were the difficulties involved and the pressures on the dockyard that the idea did not proceed. Though decommissioned, Gnat ended her days, still fighting, as an anti-aircraft gun platform at Fanana.