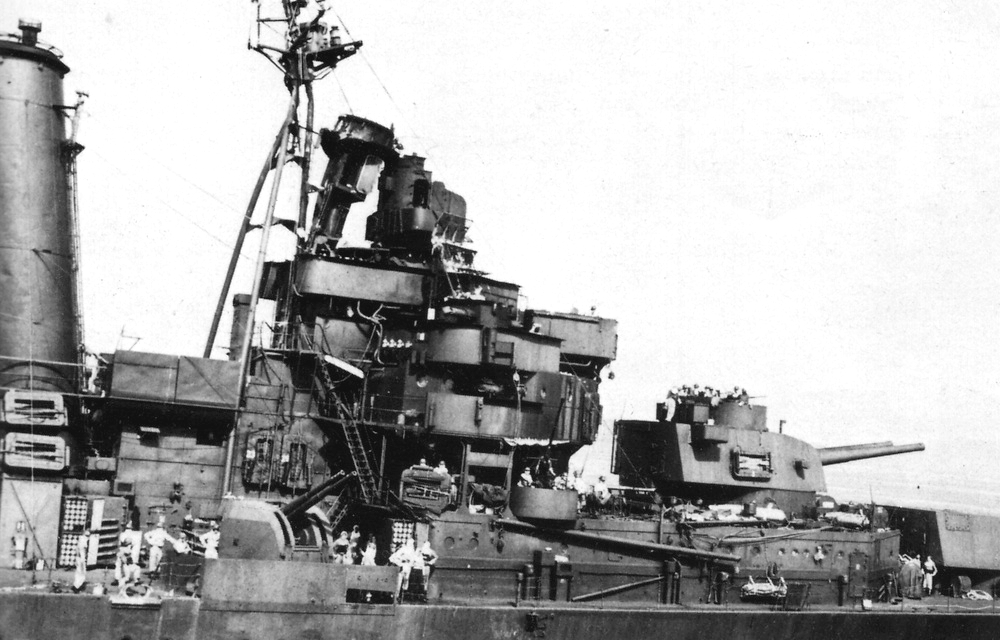

The damage to Australia’s bridge and foremast following the aerial attack of 21 October 1944.

Left: Captain EFV Dechaineux who, along with 29 officers and sailors, was killed in the Japanese dive bomber attack of 21 October 1944. Right: Lieutenant DJ Hamer, RAN was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for gallantry, skill and devotion to duty while serving in HMAS Australia during the successful assault operations in the Lingayen Gulf, Luzon Island.

Douglas MacArthur’s next move was towards Luzon, the Philippines’ biggest island and home to the capital, Manila. This was still firmly in Japanese hands. Invasion day was set for 9 January 1945 at Lingayen Gulf, in the island’s north-west corner, an almost rectangular expanse of water about 30 kilometres wide and 50 kilometres long, fringed by sandy beaches ideal for putting troops ashore.

This would be the biggest amphibious operation yet mounted in the Pacific. After a massive naval bombardment, the US 6th Army would land about 68,000 GIs on S-Day alone, building up to more than 200,000 in the following few days. The planners did not expect Lingayen to be heavily defended on land and nor did they anticipate any significant attempt by the enemy to meet the invasion at sea, although they were prepared for it. Danger would come from the sky, from a possible 800 or so land-based fighters and bombers estimated to be in the Philippines. More, perhaps, could be sent from Formosa or the Netherlands East Indies.

Vice Admiral Kincaid’s 7th Fleet would run the naval side of things – yet another armada of transports and the battleships, carriers, cruisers and destroyers to support them: warships by the hundred. As he had done at Leyte, Vice Admiral Jesse Oldendorf would command a significant part of this fleet, the Bombardment and Fire Support Group – Task Group 77.2 – of six battleships, 12 escort carriers, eight cruisers and 46 destroyers, including Australia, Shropshire, Arunta and Warramunga. The route to Lingayen would be from an assembly point at Leyte Gulf, then south-west down the Surigao Strait of recent memory, with a turn to the north-west for a more or less direct course through the Sulu Sea along the western perimeter of the Philippines islands, a journey of three days.

First away was a Minesweeping and Hydrographic Group, some 85 ships in all, including the Australian frigate Gascoyne and the sloop Warrego, which left the gulf on Tuesday 2 January at a dogged ten knots, the usual drudgery of keeping pace with the slow-movers. Oldendorf sailed the Bombardment Group before dawn on Wednesday 3 January, the sun rising on the port quarter to bring on a bright blue day with the odd bank of cumulus cloud and a light breeze that ruffled the water into small white feathers.

The calm was too good to be true, and so it turned out. It was Tiger Country again. At 7.30 am, about ten bogeys appeared, all from different directions, three of them aiming fast and low for Gascoyne. Two bombs fell well clear of her starboard quarter, but a third whistled alarmingly across her fo’c’sle and splashed into the sea just a few metres abreast of her bridge, also on the starboard side, although without exploding. If it had gone up, it may well have holed her and sunk her. Four of those aircraft were shot down, but it was by no means the end of the affair. The enemy was gathering.

Soon after 5 pm the next day, about halfway into the trip, a dive bomber flashed into sight at about 15,000 feet, peeled off into an almost vertical dive and crashed into the flight deck of the escort carrier Ommaney Bay in a blinding explosion that killed 93 men. The crew abandoned the burning hulk and she had to be sunk by a destroyer. Nerves were fraying, and that evening some of the ships – including Shropshire – began firing at a strange light in the sky, which, to wry grins all round, turned out to be the planet Venus.

Friday began quietly enough, again in weather so gloriously calm and clear that it seemed to mock the dangers and the fears. In the Australian ships, as the morning wore on, men munched on a bully-beef sandwich at their action stations, those on deck constantly scanning the skies for the hated enemy – or the flies, as they had begun to call them, the murderous, pestilential flies.

They came shortly after 4 pm, when the convoy was about 140 kilometres west of Subic Bay to the north-west of Manila, and there were waves of them both high and low, as many as 50 or 60 bombers and fighters. The air was filled with the roar of engines, the chatter and bark and crash of gunfire, the mushroom puffs of smoke from the exploding anti-aircraft shells, and the crump of bombs erupting in columns of water. Nothing should have been able to survive such a barrage, but some flies did.

Arunta was struck first. She was out on the destroyer screen when two planes came heading straight for her at 5.30 pm. Commander Buchanan ordered 25 knots and opened fire, which sent one of the aircraft sheering off, but the other – a Zero with a bomb slung beneath it – headed straight for the bridge, growing bigger with every second. Buchanan flung his helm hard over for an emergency turn to starboard and the destroyer answered it handsomely, the plane missing by a couple of metres and plunging into the sea to port. But the bomb blew a hole in her side, killing one able seaman instantly and wounding a petty officer, who died the next day. Her steering gear jammed and it took long into the night to fix it, all the while guarded by a slowly circling American destroyer.

In Australia, at the rear of the Bombardment Group, David Hamer, the Air Defence Officer, was calling the action from the air defence position, directly behind and above the compass platform, his voice crackling through the ship’s loudspeakers:

Group of Bogies bearing 265, 50 miles, closing. Friendly fighters bearing 260, closing Bogies. All AA positions stand by to close up …

Friendlies have intercepted but some bogies have broken through. Range now only 20 miles. Close up tight! All positions look out bearing red 90. Keep a good lookout on the disengaged side …

Zombies Red 80, low on the water …

Alarm port, Red 80, low on the water, six aircraft …

It was 5.35 pm. Australia opened up with everything she had, her 8-inch main armament, the 4-inch high angle, the pom-poms and finally the closer range Oerlikons, in hellish symphony. Three aircraft made it through, three Zeros. The first was hit, bursting into flames and diving vertically into the sea. The second had its tail blown off, sending it smashing across the flight deck of the nearby carrier Manila Bay, with 14 killed. David Hamer had his eye on the third Zero:

This last fellow’s coming right for us. He’s crossing ahead. Starboard side stand by. Starboard side open fire!

He’s turning towards us. Now he’s turning right over the top of us. Look out, he’s coming in!

John Clarke, a 20-year-old able seaman from Preston in Melbourne, was on the starboard pom-pom as that third plane shot across Australia’s bow:

I turned the gun onto him when he was about 150 yards on our starboard beam. Then he did an amazing thing.

He climbed straight up into the air until he reached about 200 feet, then rolled over onto his back. As he went up he seemed to stop right in the centre of my sights. The red spot on his side vanished as the pom pom hit him.

He rolled over and screamed back at us with wings at right angles to the water. As he came in we poured everything at him. About 100 feet from the ship’s side he was a flaming ball with two wings. Then I realised that nothing would stop him and with a great crash and a flash of flaming petrol he hit us.

I was thrown right off the gun to find myself in the cover of the whaler which was stowed abaft our mounting. Then there was the job of getting back to the gun, which was pointing straight up in the air and still firing away by itself. On reaching the gun I turned her off, then the remainder of the crew having returned we set about reloading and filling her up with water to get ready for another attack.

Clarke was lucky. The plane had rocketed past him between the second and third funnels, to crash on top of one of the aircraft cranes and the P2 4-inch mounting, the rearmost 4-inch gun on the port side. Every man in that gun crew was killed. So, too, were eight men at the P1 gun, and still more at the pom-poms and in the ammunition supply parties. A total of 25 men died in just those few terrifying minutes of carnage and the fire that followed, with 30 wounded. More might have been killed but for the daring of Stoker Petty Officer Merv Evans, of North-cote in Melbourne, who struggled to get a hose into the seat of the fire and stopped it spreading to a nearby ready-use ammunition locker. John Clarke, shaken to the marrow but still alive, did what he could for his shipmates at the P2 gun, but it was precious little:

Sailors had died right on the job; one man had his hand still on the interceptors and he had died in the act of closing them. The crew were lying around the gun, some with shells in their hands, and the thing that struck me most was that every man was still at his station.

Along the upper deck we could see more dead and wounded and our gun had not escaped. The captain of the gun had been very badly wounded in the legs and there were one or two shock cases … we were nauseated and completely at a loss to know what would next go on. We didn’t talk much that night, and we didn’t feel like having anything to eat.

We had a short sleep, knowing that next morning was to take us into the mouth of the Gulf …

Strangely, and for all the human loss, the damage to the ship herself was relatively slight. She could carry on, and she did, and so did her men with her, anguished and grieving though they were. On the way to Leyte, Jack Langrell had been chatting with a mate, Henry O’Neill, a 34-year-old leading seaman who’d joined the navy in 1928 and was the gun captain on P2. O’Neills were always nicknamed ‘Peggy’ in the navy. Both men had been through the fatal attack the year before, and they were tossing up their chances. ‘We’ll be all right, Peggy,’ Jack told him.

That evening, as the sun went down, Jack was one of the working party helping to retrieve the bodies, to carry what was left of them and to lay them out for the sailmaker on the fo’c’sle by the breakwater. He found Peggy with his face blown off.

Other men were also shockingly burnt and maimed. Some were naked or nearly so, their battledress stripped away. They were sewn into their hammocks that night, each one of the 25 sad bundles weighted at the feet to sink it, and the next day they went over the side. There was nothing else to do. Bodies could not be stored in the heat. Australia had no chaplain at this time, and the ship was at action stations, in Tiger Country. There was no funeral service for them, no rite of farewell and burial, no fine words, no soaring requiem, no rifle fired, no bugler sounding a plangent ‘Last Post’ – only a final drop into the cruel sea. ‘You might have given a mate a bit of a quiet blessing, but that was it,’ Jack said.

The captain carried them and the ship. As the plane attacked, he remained standing on the for’ard end of the bridge, unflinching, while – as the navigator, Commander Jack Mesley, recalled – ‘most of the rest of us tried to dig holes in the deck with our bare hands, from a prone position’. Armstrong got the damage reports as they arrived, and it was clear to him, and to Commodore Farncomb, that Australia should persevere. What was left of the crane was shoved over the side. The terrible problem would be replacing the gun crews, asking new men to step up to take the places of their dead shipmates. This they did, with some hurried training on the spot.

Though she was in the thick of it, Shropshire went unscathed, and the armada swept on through the night for its entry into Lingayen, where it would begin softening up the defences for the invasion proper three days later.

Saturday 6 January brought good weather again, ideal for air attacks. Shropshire’s action cooks threw together a breakfast scathingly described as ‘one bottle of tomato sauce to four gallons of hot water … swimming in this messy concoction were a few thin “streaks” of spaghetti’. Arthur Cooper, the Chief Gunner’s Mate, with memories of the Mediterranean, cracked that if that’s what the Italian Navy had lived on, ‘it’s no wonder they turned and ran away’.

By 10.45 am, both Shropshire and Australia were in their assigned positions to bombard Poro Point, at the eastern mouth of the gulf, and their 8-inch guns opened up.

The flies started to arrive just before noon, beginning a wave of Kamikaze attacks that brought frightening death and destruction for the rest of the daylight hours and into the evening. Again, the skies were rent by the sights and sounds of air combat. The first to be hit was the battleship New Mexico, struck by a plane that flew past Shropshire’s starboard side at masthead height, had its tail shot off and caught fire. It stayed in the air long enough to crash on the battleship’s bridge, killing, among others, her captain and a British observer, Lieutenant General Herbert Lumsden, who was Winston Churchill’s personal envoy to MacArthur’s headquarters. Another Briton, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, although standing nearby, escaped unscratched.

And on it went, in rising fury. Within a few hours, all before sunset, a minesweeper was sunk and another battleship – California – along with three destroyers and two cruisers were crashed into and badly damaged, including the heavy cruiser Louisville, which lost 41 dead, including a rear admiral.

Then it was Australia’s turn again. At 5.34 pm, her lookouts and gunners saw a Val dive bomber out to starboard, coming at them straight out of the lowering sun, across the water at a height of maybe 15 metres. The 4-inch opened up first, but the plane kept coming. John Clarke, still at his pom-pom, got him in the crosshairs of the gun sight and opened fire:

As he came on, the plane was almost obliterated by the bursting shells pouring out at 1000 a minute. Still he came, but now he was starting to go down in a shallow dive towards the water. For a moment it looked as if he would hit the sea, but he jerked himself up just before his tail unit dropped into the water. Then, about 50 yards from the ship, his port wing dropped off and immediately he swung off course and with a terrible rending crash he hit the upper deck. Had it not been for his wing coming off I would not be telling this story, for he was coming right at the gun and I would have got him right between the eyes. All the way in he had been firing his guns, and one cannon shell passed between our heads and burst in the ready use magazine where we had over 2000 rounds already laid out on the deck for loading. Had it struck them the magazine would have been blown to pieces and all the gun’s crew with it.

Another 14 men died, including the whole of the S2 gun crew and most of the men at the S1, with another 26 wounded. And there was an insult added to death and injury in this attack: the Val had been carrying a bomb made from a British 15- or 16-inch naval shell with an impact fuse fitted on its nose, possibly one obtained at the naval base in Singapore. They could tell because they found identification and lettering in English on the remains of the shell’s base plate. Yet, again, the damage to the ship was not as bad as it might have been. Although the impact had gouged another hole in the teak decking, the blast of the bomb went upward and the fires were quickly put out. Parts of the pilot’s body were found in the blackened debris and were swept unceremoniously over the side.