At Westkapelle, however, the story was very different. The assault was to be delivered at the breach in the dyke just south of the town, but the sea approaches to this were covered by three major coast defence batteries. To the north of the gap were Battery W.17 at Domberg, armed with four 220mm French guns and one 150mm gun in open concrete casemates, and Battery W.15 on the northern outskirts of Westkapelle, armed with four British 3.7in AA guns in concrete casemates and two British three-inch AA guns in open emplacements, all of which had been converted to the coast defence role; south of the gap, between Westkapelle and Zoutelande, was Battery W.13, armed with four 150mm guns in concrete casemates, two 75mm guns in casemates and three 20mm AA cannon.

Because of this the landing force would have direct support from the 15in guns of the battleship HMS Warspite and the monitors HMS Erebus and Roberts, which would open fire at 0815, joined twenty minutes later by the First Canadian Army’s medium and heavy artillery, firing across the Scheldt from Breskens. Escorting the landing craft during their run in towards the beach would be a Close Support Group containing 27 LCGs (Landing Craft Gun) and LCT(R)s (Landing Craft Tank (Rocket)).

Sea conditions were good but mist blanketing airfields in England had kept the promised air support grounded, although it was expected to clear. It also grounded the Bombardment Group’s spotter aircraft so that Warspite and the monitors were forced to fire by dead reckoning. As a result, their heavy shells did less damage than was expected until the Artillery Air OP light aircraft arrived from Breskens; for a while, too, Erebus was forced to cease firing because of mechanical problems in her turret. Bursting shells began to fountain around the Support Group while it was still some four miles short of the shore, but seeing that the German fire had not been appreciably reduced, the gun and rocket craft closed in to conduct a deadly and one-sided duel with the enemy batteries. Their self-sacrifice succeeded in concentrating most but by no means all of coastal gunners’ fire on themselves, and it eliminated a number of smaller posts and pillboxes, albeit at terrible cost; nine of the craft were sunk, eleven were put out of action with serious damage, and of the 1000 Royal Naval and Royal Marine personnel who provided their crews 192 were killed and 126 seriously wounded. At the critical moment, flight after flight of rocket-firing Typhoons roared in to strafe the defences, enabling the LCIs and LCTs to ground and disgorge their Buffaloes, which secured the shoulders of the breached dyke or passed through to assault Westkapelle from the rear.

The armoured assault team, carried in four LCTs, had the worst landing in the division’s experience. ‘One craft was hit repeatedly, the SBG bridge shot away from its AVRE and a fascine AVRE set on fire. By the efforts of its crew, explosives were jettisoned and the fire put out. The craft was later ordered to withdraw back to Ostend. The second LCT, Cherry, was hit hard astern and had many casualties, forcing it to withdraw and come in later. The third, Bramble, was able to touch down among broken boulders. The first AVRE to get ashore bellied (in the mud), so the craft pulled out and beached on sand further south. Two Crabs made heavy going of it but got up the beach; a bulldozer followed but the SBG was hit by a shell and the AVRE stuck. Cherry beached further south and offloaded all but one Crab, which was inextricably tangled up in the vessel’s bridge which had been wrecked by fire. The bulldozer, in an attempt to recover the bellied AVRE off Bramble, sank itself in a quicksand.

‘About this time Sergeant A. Ferguson (1st Lothians) fired eleven rounds of 75mm at the church tower east of Westkapelle which was being used as an observation post. The tower burst into flames and Germans came running out. Westkapelle had almost been cleared by the commandos but heavy shelling and mortaring of the beaches went on. All over the shore Buffaloes and Weasels were searching for an exit. Two Buffaloes loaded with ammunition were burning fiercely – in fact the beach was covered with smashed and burning vehicles and casualties were mounting.

‘The fourth LCT, Apple, landed on the left. The first Crab got ashore but stuck when it tried to tow the second off. The bridge AVRE disembarked, laid its SBG over some bad going, crossed it, then bogged, which blocked the way of the second AVRE already on the bridge. In spite of all efforts both tanks were drowned by the rising tide.

‘The tanks had found a small gap through the rocks but the sand was soft and they spoiled it completely for other vehicles. However, by dint of great perseverance and sterling work under shell and mortar fire, two Shermans, two AVREs, two Crabs and a bulldozer reached the village. They worked right through it dealing with roadblocks and houses and filling in craters with the bulldozed rubble and trees. That night the tide through the breach rose so high that the two Crabs were drowned.’

During the afternoon Battery W.13 surrendered to 48 Royal Marine Commando; one of its 150mm casemates had been cracked, killing the crew, and the remaining big guns had expended their ammunition. 41 Royal Marine Commando stormed West-kapelle village and Battery W. 15 at about noon, then moved north to tackle Battery W. 17 at Domburg, which gave up without a fight shortly after dusk. Resistance in this area, centred on Domburg village and a number of smaller concrete strongpoints among the dunes to the north, now became stiffer, and for the next six days the armoured assault team, reduced to two Sherman gun tanks and two AVREs, was fully engaged in supporting 41 Commando and No 10 Inter-Allied Commando as they fought their way along the coast towards Veere. Both AVREs eventually fell victim to mines, but the Shermans soldiered on to the end, firing no less than 1400 rounds of 75mm AP and HE. Later, Hobart received a personal note of thanks from Brigadier B. N. Leicester, commanding 4 Special Service Brigade: ‘I want to let you know how very well your chaps did….The few tanks we got ashore were worth their weight in gold….In the north we had no close-supporting fire other than three machine-guns which were of little use against concrete. There the tanks consistently and successfully supported troop attacks on concrete by 75mm, the accuracy of which was a pleasure to watch – I saw them! Their Brownings too had a most heartening effect in keeping the enemy infantry to ground.’

After the coastal defences had been stormed and Flushing was captured, the remaining German resistance was centred on the fortified town of Middleburg in the centre of the island. As this was surrounded by flooded terrain, the garrison felt reasonably secure, but on 6 November the Buffaloes of A Squadron 11 RTR, with 7th/9th Royal Scots aboard, set out from Flushing to prove them wrong. The direct route lay along the banks of the Flushing-Veere Canal, but this was mined and covered by anti-tank guns and machine-guns. Under the guidance of a Dutch civilian, a more circuitous route over inundated countryside to the west was adopted. Thus far the enemy, drawn mainly from the 70th Division (nicknamed the White Bread Division because most of its men had stomach ailments), had put up a remarkably tough fight, but so surprised and demoralised were they by the sudden arrival of the leading infantry company in eight Buffaloes that they offered no resistance. The German garrison commander, Lieutenant General Wilhelm Daser, indicated his willingness to surrender, but not to a junior officer, a difficulty which was resolved by supplying the infantry company commander with a badgeless raincoat and according him local and temporary promotion to lieutenant colonel.

Between 1 October and 8 November the First Canadian Army had sustained 12,800 casualties, half of them Canadian, from all causes. In return, over 41,000 prisoners had been taken and both banks of the Scheldt had been cleared. Minesweeping had begun even before Walcheren surrendered and the first cargoes reached Antwerp on 26 November.

The 79th Armoured Division continued to provide specialist armoured teams for the whole of 21st Army Group, plus the US First and Ninth Armies, and were engaged in a variety of operations spread across a wide area. On 16 December a major German counter-offensive was launched through the Ardennes with the object of recapturing Antwerp, but the only elements of the division to become involved in the subsequent fighting, collectively known as The Battle of the Bulge, were the two Kangaroo regiments and one troop of 11 RTR’s Buffaloes.

The counter-offensive failed, although it did delay Allied plans for an advance to the Rhine by approximately six weeks. After the threat had passed, 79th Armoured Division commenced detailed planning for Operation ‘Veritable’, 21st Army Group’s eastward drive through the Reichswald Forest into the Rhineland. For this, the initial allocation of specialist armour was as follows:

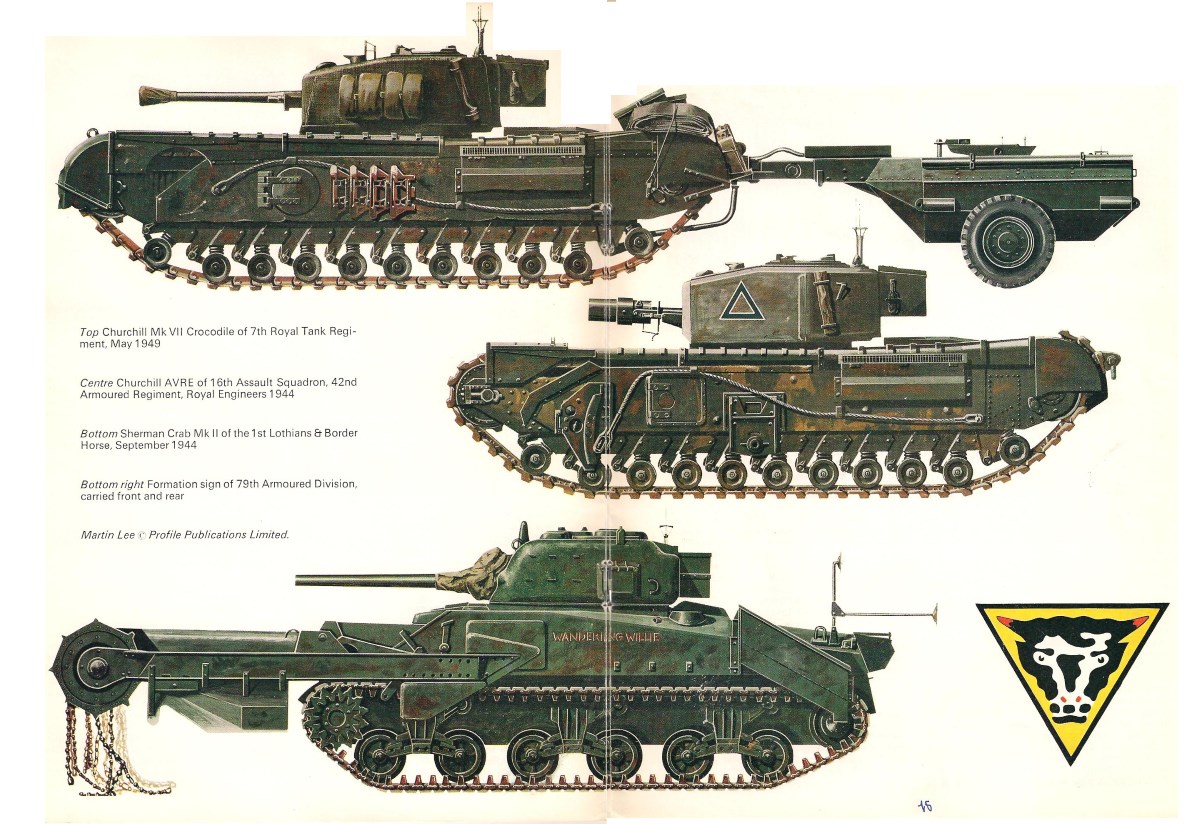

15th (Scottish) Division: One regiment of Crabs, two squadrons of AVREs, two squadrons of Crocodiles and both Kangaroo regiments;

51st (Highland) Division: One squadron each of Crabs, AVREs and Crocodiles;

53rd (Welsh) Division: Two squadrons of Crabs and one squadron each of AVREs and Crocodiles;

2nd and 3rd Canadian Divisions: One squadron each of Crabs and AVREs, four squadrons of Buffaloes.

Following the heaviest preparatory bombardment fired by British artillery in World War II, Veritable commenced on 8 February 1945. Conditions were atrocious, continuous rain having produced deep mud, while on the northern flank the Germans breached the dykes protecting the Rhine flood plain, which now lay under five feet of water moving at a speed of eight knots. The Reichswald itself consisted of close plantations and was considered by some German officers to be tank-proof on its own account; in addition, it also contained a northern extension of the Siegfried Line, and while the concrete structures for this had not been completed, there were bunkers, minefields and anti-tank obstacles. Holding the area was the 84th Division, which had twice been bled white since the Normandy landings and had recently been reinforced with more units consisting of men with medical conditions; this was not expected to put up much of a fight, but in immediate reserve were troops of the German First Parachute Army who could be relied upon to contest every foot of ground.

During the early days of the battle the appalling going again provided the armoured assault teams with more problems than the enemy. Wallowing slowly forward through the morass, the vehicles bellied and towed each other free in agonising slow motion, with chilling rain sheeting down on them the while; at one stage it was estimated that three-quarters of the tanks in the forest were bogged down. Yet, somehow, lanes were cleared of mines by the Crabs, anti-tank ditches were bridged or filled in, and bunkers petarded or flamed into submission. On the right and in the centre only the Churchill gun tanks of the infantry-support tank brigades and the Churchill-based Crocodiles and burden-free AVREs were simultaneously able to cope with the mud and splinter their way through the trees. The commander of one captured feature went so far as to pass the outraged comment: ‘We had never thought that anyone in their right mind would use tanks in this forest; it is most unfair!’ On the left, where the flooding was total, the Canadians mounted their attacks in assault boats, supported by fire from Buffaloes, and were supplied by Weasels and DUKWs.

It was this ability to retain mobility that the Germans found most unsettling. As the rains became less frequent and the floods started to subside, they rushed nine more divisions to the threatened area, drawn from the American sector of the front. This suited the Allies very well for on 23 February the US Ninth Army, forming the right wing of 21st Army Group, seized crossings over the river Roer at a cost of less than 100 casualties and, breaking out of its bridgeheads a week later, its armour reached the Rhine on 2 March. The effect was to isolate First Parachute Army, still locked in its bitter struggle with the British and Canadian divisions to the north, so that von Rundstedt, the Commander in Chief West, had no alternative other than to withdraw what remnants he could across the river. Together, the Reichswald battle and the American offensive had cost the German Army some 90,000 men. The British sustained 10,330 casualties, the Canadians 5304 and the Americans 7300.

Plans were already in hand for the crossing of the great waterway. These included use by 79th Armoured Division of a device cloaked in such secrecy that, although units had been equipped with it since 1942, it had never been used operationally by British troops, an omission described by Fuller as the greatest blunder of the war. The device was a British invention known as the Canal Defence Light (CDL) and it consisted of an M3 Lee/Grant chassis and hull fitted with a specially designed turret housing a 13 million candlepower carbon arc the intense light from which was reflected through a narrow slit controlled by the rapid movements of a mechanically driven shutter. The flickering effect of the light induced temporary partial blindness, sometimes accompanied by nausea, loss of balance and disorientation, and it also prevented the enemy identifying its source or even whether it was moving or stationary. Tactically, it was possible for troops to advance towards their brilliantly illuminated objective, yet remain completely invisible in the dense black space between two CDL beams. The Americans were also interested in the idea and had formed CDL units, although they codenamed the vehicle the Shop Tractor. Once again, however, obsessive secrecy had prevented its use until, even as 21st Army Group was completing its preparations for crossing the Rhine, the US 9th Armored Division seized the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen by coup de main and a CDL unit was successfully employed to defend the structure against attacks by German frogmen; even this local usage had required the personal sanction of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied Supreme Commander. On the British sector the CDLs were to be used in a similar fashion, as well as providing directional light for the Buffalo crossings, requiring B Squadron 49 RTR, one of the original CDL units, to abandon its Kangaroos and retrain in the role.

For the Rhine Crossing, codenamed ‘Plunder’, and the subsequent expansion of the bridgeheads secured, 79th Armoured Division effected the greatest concentration of specialist armour since D Day. This included two DD regiments (Staffordshire Yeomanry and 44 RTR) and three additional Buffalo regiments (1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry, 1st East Riding Yeomanry and 4 RTR). The lessons of South Beveland and Walcheren had been learned and, to assist the DDs in climbing the floodbanks, they would be accompanied by a number of specially adapted Buffaloes that would unroll a chespale carpet ahead of them where necessary. As few permanent defences existed on the east bank of the river there was no immediate requirement for AVREs and assault regiments RE were given the task of manning motorised rafts which would be used to ferry non-DD tanks and other vehicles across in the wake of infantry divisions.

The allocation of units from 79th Armoured Division to the higher formations involved in the crossing was:

BRITISH SECOND ARMY

British XII Corps: two regiments plus one squadron of Buffaloes, three assault squadrons RE manning motorised rafts, one regiment of Crocodiles, two squadrons of Kangaroos, one Crab regiment, one half-squadron of CDLs and one DD regiment.

British XXX Corps: two regiments of Buffaloes, three assault squadrons RE manning motorised rafts, three squadrons of Crocodiles plus one in corps reserve, one squadron of Kangaroos, one squadron of Crabs plus two in corps reserve, one half-squadron of CDLs and one DD regiment.

US NINTH ARMY

US XVI Corps: one squadron of Crocodiles, one squadron of Crabs.

Plunder was the sort of huge set piece operation in which Montgomery excelled. The river crossing, supported by air attacks and the fire of 3300 guns on a 25-mile frontage, commenced at 2100 on 23 March. The six understrength German divisions on the east bank could only offer weak resistance and by morning bridgeheads had been established with very few casualties; before the enemy could recover his balance the US XIX Parachute Corps (British 6th and US 17th Airborne Divisions) had been dropped behind him. Armour began to flow across the river and, day by day, the bridgeheads were expanded until the point was reached when the German Army, with nothing in reserve, was unable to contain them. The war had only weeks to run.

For the Royal Tank Regiment the Rhine crossing was memorable in a number of ways. Lieutenant Colonel Alan Jolly, commanding 4 RTR, crossed with the same brown, red and green flag flying from his Buffalo that the 17th Battalion Tank Corps had flown when their armoured cars reached Cologne at the end of World War I. On 26 March 11 RTR’s Buffalo crews on the east bank were rounded up to meet one of their vehicles that was carrying more brass hats than they had ever seen in one place. The men were deadly tired and hollow-eyed, their battledress crumpled and their boots plastered with mud. Their days involved many hours of continuous work, with a few precious intervals for rest and sleep, and the arrival of the generals was less than welcome. As the VIPs clambered down, however, they began to take more interest. Major General Hobart, their divisional commander, was of course a familiar figure; equally familiar, although not many had seen him in the flesh, was the Army Group commander, Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery, casually dressed and wearing their own black beret; some probably recognised Lieutenant General Neil Ritchie, commanding XII Corps, but not many could have put a name to Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, or to General Sir Miles Dempsey, commander of the British Second Army. Yet it was a cherubic figure wearing only a lieutenant colonel’s insignia on the shoulder straps of his British Warm, and the badge of 4th Hussars, his old regiment, in his standard service dress cap, who attracted most attention. As he called the men to break ranks and gather round delighted grins began to spread and there were astonished exclamations of: ‘It’s Winnie!’ The Prime Minister congratulated the men on their efforts and Montgomery, completely relaxed after the success of the operation, urged them to take advantage of the situation: ‘Go on, ask him for a cigar!’ At that precise moment, it would have been strange for one so steeped in a sense of history if Churchill had not reflected on how armoured warfare had developed since he had encouraged its first painful beginnings some thirty years earlier. Later, he visited the US Ninth Army’s bridgehead, causing near heart failure among senior American officers by repeatedly exposing himself to danger.

The CDLs of B Squadron 49 RTR had also fulfilled their promise. They naturally attracted much of the enemy’s fire, and consequently were unpopular neighbours, but they were difficult to locate and only one tank was lost. From 25 March until 6 April their role became the night defence of the pontoon bridges which the engineers had worked at top speed to complete. Three frogmen were exposed by the flickering beams and captured, and a large number of floating objects were engaged and sunk. Some of the latter exploded and while most of these devices were primitive mines consisting of logs to which charges had been strapped, one was thought to be a midget submarine, of which the Germans had several types. The CDL squadron followed up the advance into central Germany and was in action again during the crossing of the Elbe at the end of April.

During the last month of the war in Europe 79th Armoured Division was again dispersed across a very wide area, assisting in the liberation of those parts of Holland still under German control, driving north to participate in the capture of Bremen and Hamburg, and east until contact was established with the Russians. One of the most remarkable facts about the division’s history was that the nature of both its equipment and the operations it undertook was successfully concealed from the general public until after the Rhine Crossings. The media then received appropriate releases, resulting in a series of sincere if over-enthusiastic tributes, some of which fell just short of claiming magical powers.

At this period the divisional strength amounted to 21,430 men and 1566 armoured fighting vehicles; the strength of a conventional armoured division was about 14,400 men and 350 AFVs. 79th Armoured Division was a unique formation, although a similarly equipped but much smaller assault brigade supported the British Eighth Army’s final offensive in Italy. ‘Hobo’s Funnies’ were disbanded in 1945, and although assault engineering techniques have reached new levels of sophistication, no formation of the same size and scope as Hobart’s division has been formed since, for the good reason that the circumstances that called it into being have mercifully never been recreated.