If, superficially, this suggests an absurdly cheap victory, it must be compared with what happened on the American sectors where, it will be recalled, the troops did not have the benefit of armoured breaching teams. On Utah Beach their task had been eased somewhat by the dropping of the US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions some miles inland during the previous night; but on Omaha Beach the US 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions were pinned down on the shore by defences that were no more formidable than those on the British sector. Not until an hour after the initial landings did the situation begin to improve slowly when eight American and three British destroyers, observing the carnage amid the shattered LCIs at the water’s edge, closed in to batter the defences at point blank range. Even then, it was only by the inspired leadership, heroism and self-sacrifice of individuals and small groups that the Americans began to make ground little by little. By midnight, while the other beachheads were between seven and nine miles deep, that at Omaha amounted to a foothold extending at best some 2000 yards from the shoreline. The cost had been 3000 casualties, half the American losses for the day, including that of the two airborne divisions; British and Canadian casualties at Gold, Juno and Sword Beaches amounted 4200 killed, wounded and missing.

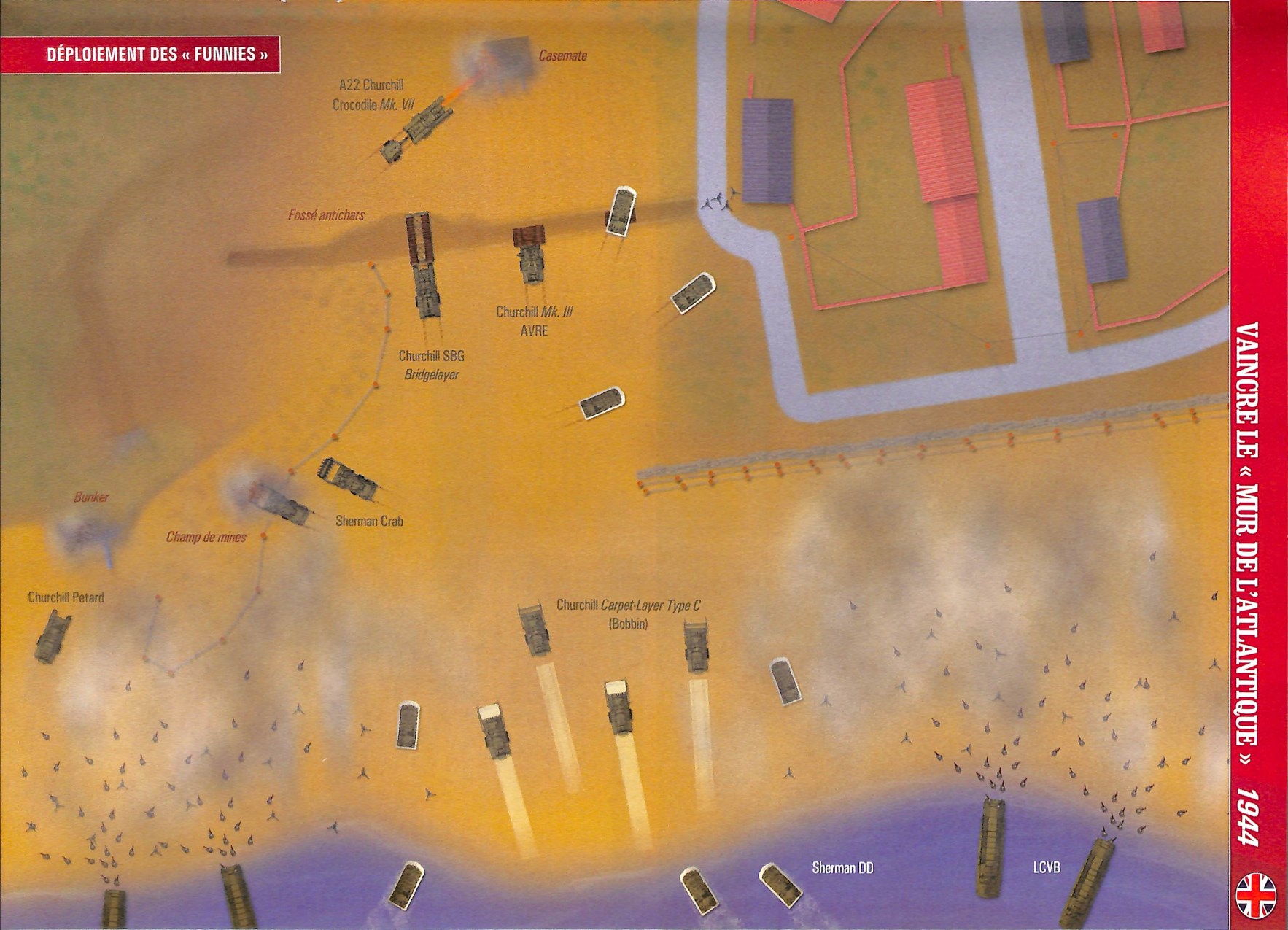

The events of D Day demonstrated beyond any possible doubt the validity of Hobart’s tactical concepts and his thorough training methods. For the remainder of the campaign in North-West Europe elements of 79th Armoured Division, now known throughout 21st Army Group as ‘Hobo’s Funnies,’ played a vital part in every major and countless minor operations fought by the British and Canadian armies, as well as providing support for the Americans when requested.

Enough has been written on the conduct of operations in Normandy for only the briefest of reminders to be given here. Although the terrain, much of which consisted of small fields bounded by hedges set on earth banks, favoured the defence and was far from ideal tank country, the Allied strategy was for the British and Canadian armies to maintain constant pressure and thereby draw in the bulk of the German armour while the Americans prepared to break out into the open country to the south and east. To achieve this a series of major operations – Epsom, Jupiter, Charnwood, Goodwood and Bluecoat – were mounted throughout June and July, wearing down the German strength in heavy attritional fighting. The American breakout, codenamed ‘Cobra’, commenced on 25 July and proved to be unstoppable; concurrently, at the northern end of the front, the Canadian First Army was pushing slowly but steadily southwards from Caen towards Falaise. With both their flanks now hanging in the air, the German armies were compressed within a pocket from which comparatively few escaped. By 21 August the fighting in Normandy was effectively over.

While these operations were in progress 79th Armoured Division received a new weapon which had not been employed during the D Day landings. This was the fearsome Crocodile, consisting of Wasp flamethrowing equipment fitted to a Churchill VII which was coupled to a two-wheeled armoured trailer holding 400 gallons of inflammable liquid. From the coupling, a pipe led under the tank’s belly to emerge into the driving compartment where it joined the flame gun, which replaced the hull machine-gun. On leaving the flame gun the liquid was ignited electrically and propelled in a jet to a range of 120 yards, clinging to everything it touched. The propellant gas was pressurised nitrogen, housed in cylinders inside the trailer, permitting flaming for a total of 100 seconds in short bursts. Once the flaming liquid had been expended the trailer could be dropped, leaving its parent vehicle free to fight as a gun tank. Naturally, the Crocodile was hated and feared by the enemy, whose anti-tank gunners would attempt to knock out the trailer before it could be brought within range. Often, however, the appearance of a Crocodile was in itself sufficient to induce surrender; on the other hand, incidents occurred in which captured Crocodile crews were shown no mercy. The division possessed three Crocodile regiments – 141 Regiment RAC, 1st Fife and Forfar Yeomanry and 7 RTR – which together formed 31st Tank Brigade.

Another class of vehicle was added to the divisional armoury as a direct result of the fighting in Normandy, thanks to Lieutenant General Guy Simonds, the 41 year old commander of the Canadian II Corps, whose innovative ideas often complemented those of Hobart. The Allies had sometimes resorted to concentrated carpet bombing to blast their way through a sector of the enemy’s front. This certainly obliterated anything in its path, but the huge crater fields made life very difficult for armoured vehicles trying to penetrate the gap, as any World War I tank crewman might have predicted. In planning Operation ‘Totalize’, the Canadian drive in the direction of Falaise on 8 August,

Simonds hit on the novel ideas of using bomb carpets to protect the flanks of the advance, and mounted his infantry in makeshift armoured personnel carriers. At this period the Allied armoured divisions’ organic infantry were equipped with the M3 armoured half-track, but the infantry divisions had no APCs at all, save for their small tracked weapons carriers. Simonds therefore had the guns stripped out of a number of M7 Priest Howitzer Motor Carriages, which were then capable of carrying twelve infantrymen apiece; inevitably, these weaponless versions of the M7 were known as Unfrocked Priests. The idea worked so well that it was decided to convert turretless Sherman and Canadian Ram tanks to the role; with equal inevitability, the APC family so created were referred to a Kangaroos. Two APC regiments – 49 RTR and 1st Canadian APC Regiment – were formed with 150 Kangaroos each and attached to 31st Tank Brigade.

After Normandy, the first major operation involving 79th Armoured Division was the capture of the Channel Ports. Hitler had given specific instructions to the garrison commanders that they were to be denied to the Allies at all costs and each was protected by a cordon of fortified areas which included an anti-tank ditch, minefields and numerous concrete strongpoints. These were studied in detail and assault teams formed to deal with them – Crabs to clear lanes through the minefields and provide direct gunfire support, AVREs with SBG bridges and fascines to fill in the anti-tank ditches, and AVREs and Crocodiles to tackle the strongpoints. On their own, neither AVREs nor Crocodiles could guarantee success against the thick concrete structures; the AVRE’s petard bombs might crack the concrete but they would not touch those inside; and, on the approach of a Crocodile, the defenders could retire into the inner chamber until it had finished flaming, then return to their fire slits. Together, however, they proved to be a deadly combination; once the AVRE had cracked open the structure the Crocodile would flame it and the burning liquid would flow inside, consuming the oxygen and forcing the defenders into the open.

Le Havre was assaulted by the 49th (West Riding) Division plus the 22nd Dragoons, A Squadron 141 Regiment RAC, 222 and 617 Assault Squadrons RE; and the 51st (Highland) Division plus B and C Squadron 1st Lothians and Border Yeomanry, C Squadron 141 Regiment RAC, 16 and 284 Assault Squadrons RE. The attack commenced at 1745 on 10 September and during the next two days the assault teams fought their way steadily through the defences, leaving the infantry to accept the garrison’s final surrenders on 13 September. Faced with tough resistance and extensive minefields, the teams enjoyed mixed fortunes but, as on D Day, a sufficient margin had been allowed to ensure success. Personal initiative, too, played a major part; at Harfleur, for example, the AVREs of 222 Assault Squadron RE filled in an anti-tank ditch by felling several trees with their petards. One Scottish company commander, having taken over a captured bunker as his headquarters, answered a ringing telephone and found himself talking to a German, who he invited to surrender. The suggestion was indignandy refuted, but others sharing the line had no reservations and promptly emerged from a number of neighbouring strongpoints. They had felt secure behind their minefields and were dismayed when these were breached by the Crabs, which came as a complete surprise to them; understandably, it was the Crocodiles which had shocked them most, and they described their use as ‘unfair’ and ‘un-British.’

The Americans had already taken St Malo and begun to assault Brest on 25 August. The garrison of this major port, consisting of 35,000 men under an extremely tough paratroop commander, Major General Hermann Ramcke, resisted so stubbornly that the attackers made little progress. At length General Bradley requested the assistance of Crocodiles to subdue the defences and in response B Squadron 141 Regiment RAC, commanded by Major I. N. Ryle, was attached to Major General W. E. Sands’ US 29th Infantry Division for the reduction of Fort Montbarey. This consisted of an old casemated masonry fort within a moat, surrounded in turn by concentric lines of defence incorporating 40mm and 20mm gun positions and a minefield which included buried 300 pound naval shells. On 14 September, after American engineers had gapped the minefield, a two-tank Crocodile troop, covered by the squadron’s gun tanks, led the infantry attack, burning up weapon pits as it went. One Crocodile blew up when it ran over a shell but the second continued until the American infantry had consolidated their gains around the fort itself. At this point the Germans began to emerge with white flags and the Crocodile, having exhausted its flame fuel and fired off all its 75mm ammunition, began to turn for home. As it did so it slid into an anti-tank ditch. A troop of Churchill gun tanks came forward to assist, but the first of these slid into another tank trap, the second shed a track and the third bellied in a crater. Observing this unexpected series of accidents, the enemy changed their minds, retired within the defences and opened fire again. Although disappointing in its eventual outcome, the day’s fighting yielded 122 prisoners, plus two 50mm guns, one 105mm gun and two major strongpoints captured. All the ditched tanks were recovered despite sniper fire.

Two days later the battle was resumed: ‘One troop of Crocodiles (Sergeant Decent), supported by direct fire from every available tank and self-propelled gun, crept up to the fort and rolled their flame over the moat. A gun tank pounded the main gate and three prisoners emerged. One was sent back to call for surrender – this was refused, so two more troops (Lieutenants C. Shone and T. P. Conway) gave the fort all the flame and HE they had, to the accompaniment of all guns at hand. Phosphorous and mortar bombs rained down and a 105mm gun pumped 200 more rounds at the gate. As the fire shifted to the northern edge, the sappers, under smoke, blew charges against the wall and the infantry went in. An officer with a white flag greeted them; he and his 30 men were being suffocated by smoke and phosphorous. The outhouses were blazing and after a little hand-to-hand fighting all was over. The Germans expressed their respect for flame and showed how effectively casemates had been penetrated and crews burned alive.’ The fall of Fort Montbarey made Brest untenable and on 18 September Ramcke capitulated.

Meanwhile, Boulogne was attacked on 17 September by Major General D. C. Spry’s Canadian 3rd Division, with assault teams provided by A and C Squadron 1st Lothians and Border Yeomanry, A and C Squadrons 141 Regiment RAC, 81 and 87 Assault Squadrons RE. The plan, conceived by Simonds, incorporated two phases. First, breaches were to be made in the outer crust of the defences by carpet bombing, through which infantry in Kangaroos would be carried forward to the point where cratering prevented further progress; they would then establish themselves while bulldozers carved routes across the devastated area. The second involved the assault teams, formed into three all-armoured columns, exploiting through the infantry and advancing into the town centre from different directions. The defences themselves were subjected to an additional heavy battering by the Second Tactical Air Force and RAF Bomber Command, while the Allied artillery support programme included participation by two fourteen- and two fifteen-inch coast defence guns firing across the Channel from England. In the event, the battle took the form Simonds had intended, although the severe cratering caused the assault teams as much trouble as the enemy. On the other hand, there were unexpected strokes of luck. One column, for example, was guided by a French taxi driver through the tangle of city streets, and the crews of two AVREs which had petarded the main gate of the Citadel into surrender, taking the German adjutant and 30 of his men prisoner, were considerably surprised when the next figures to emerge from the fortress were grinning Canadian infantrymen who had been ushered through a secret entrance by a member of the Resistance. The last of Boulogne’s defences surrendered on 21 September and a further 9500 prisoners began their march into captivity; the Canadians sustained only 634 casualties.

Hardly had the fighting ended than 3rd Canadian Division began moving towards its next objectives, the coastal batteries between Cap Gris Nez and Calais, and the port of Calais itself. Here the assault teams were drawn from the same units that had stormed Boulogne, save that the AVREs were manned by 81 and 284 Assault Squadrons RE. Deliberate flooding of the surrounding area restricted the approach to a heavily fortified coastal corridor from the west but, against this, almost two thirds of the 7500-strong German garrison, consisting in the main of elderly or sick men, was required to man the coastal batteries. It was apparent as soon as the attack began on 25 September that they lacked the will to fight and, having witnessed the capabilities of the assault teams, most surrendered after a token resistance. By 1 October, at a cost of only 300 Canadian casualties, the entire area had been cleared. For the first time in four years, shipping in the Straits of Dover could operate without the menace of enemy gunfire. The Lothians, having captured the German flag flying over the Cap Gris Nez gun positions, presented it to the Mayor of Dover, which had itself been a regular target of the coastal batteries.

With the exception of Dunkirk, the garrison of which was to be contained and allowed to rot until the war ended, all the Channel ports were now in Allied hands. Yet, so thorough had been the German demolitions that it would be months rather than weeks before traffic would begin flowing through them and the Allied lines of communication stretched back some 400 miles from the German and Dutch borders to the Normandy beaches. Again, while the 11th Armoured Division had captured the Antwerp docks more or less intact on 5 September, these could not be brought into use until the enemy had been cleared from both banks of the Scheldt. Therefore, even while fighting for the Channel ports was in progress, plans were being made for opening the sea approaches to Antwerp. These included augmenting 79th Armoured Division’s amphibious capability by the issue of the Buffalo LVT (Landing Vehicle Tracked, originally developed for the Pacific theatre of war) and its smaller cousin the Weasel. In British service the Buffalo could carry either 24 infantrymen, or one 17pdr anti-tank gun, or one 25pdr gun-howitzer, or one tracked Universal Carrier, or ammunition and supplies. 5 ARRE had, in fact already converted to the amphibious role and was joined by 11 RTR, both regiments being equipped with 100 Buffaloes.

The first area to be tackled was an enemy pocket on the south bank of the Scheldt, centred on the town of Breskens. When this was attacked on 6 October by the Canadian 7th Brigade little progress was made, partly because flooding had again been used to restrict the frontage, and partly because the defence was being conducted by the German 64th Division which, recruited largely from men on leave from the Eastern Front, was a very different proposition from the fortress troops encountered the previous month. However, during the early hours of 8 October 5 ARRE’s Buffaloes ferried the Canadian 9th Brigade across the mouth of the Braakman Inlet (referred to as the Savojaards Plaat in the divisional history), covering the eastern flank of the pocket, and landed in the enemy’s rear, achieving complete surprise. Major General Eberding, commanding the German troops within the pocket, reacted quickly to the threat but was unable to prevent the Canadian 8th Brigade being similarly lifted into the beachhead two days later. Now under simultaneous pressure from north and south, he shortened his perimeter, but one by one the towns in his possession fell to the Canadians and their supporting teams of Crabs, AVREs and Crocodiles. By 3 November the pocket had been cleared.

Across the Scheldt was the South Beveland peninsula, connected to the mainland by an isthmus along which the 2nd Canadian Division was slowly fighting its way forward. To accelerate the capture of the peninsula the 156th Brigade, from 52nd (Lowland) Division, was carried the nine miles across the river in the Buffaloes of 5 ARRE and 11 RTR, accompanied by eleven DDs manned by B Squadron Staffordshire Yeomanry, in the pre-dawn darkness of 25 October, direction being maintained with the assistance of bursts of Bofors tracer fired at timed intervals from the south bank. A beachhead was established and rapidly expanded without difficulty, although only four of the DDs were able to surmount the muddy dykes and accompany the troops inland. On 27 October 157th Brigade, also from 52nd Division, was ferried across and that night the 2nd Canadian Division broke through the isthmus defences to join the Scots in overrunning the rest of the peninsula.

West of South Beveland was the heavily fortified island of Walcheren, covering the entrance to the Scheldt. Diamond shaped and measuring some twelve miles by nine, most of the island lies below sea level and is protected by dykes and sand dunes up to 100 feet high. The Germans were well aware of its strategic importance and had built numerous concrete coastal batteries containing guns of up to 220mm calibre, both among the dunes and inland; beach defences included mines, posts, hedgehogs, Element C and wire. Many of these defences were neutralised when, during early October, the RAF mounted a series of raids which breached the dykes in four places, allowing the sea to flood in.

Two landings were planned, the first based on Breskens and directed at Flushing on the south coast of the island with No 4 Commando leading in landing craft, followed by 155th Brigade (52nd Division) in Buffaloes, while the second, based on Ostend, was directed at Westkapelle on the west coast with 4th Special Service Brigade coming ashore in Buffaloes launched from LCTs, plus a strong armoured assault team, which would also land from LCTs.

Both landings took place on 1 November. That at Flushing went entirely according to plan, with the commandos having the good fortune to come ashore in the one area that had not been mined, while the Buffaloes sustained comparatively small losses, despite the heavy volume of fire directed at them.