When, on 19 August 1942, the Allies mounted a major raid on Dieppe, they did so with the political object of demonstrating to Stalin that the opening of a ‘Second Front’ in the West was, for the moment, not a practical proposition. However, while the operation was ostensibly a failure, many valuable lessons were learned and put to good use in the planning of the invasion of Western Europe almost two years later.

After Dieppe the Allies recognised the impossibility of securing a heavily defended French port, deciding instead to invade over the open beaches of Normandy and bring their own prefabricated harbour with them. These beaches, while not as heavily fortified as the more important ports, nonetheless possessed formidable defences which were capable of inflicting terrible losses on a conventional landing force. The German belief was that the Allies would time their invasion to coincide with high tide, so reducing the period that their troops would be dangerously exposed while crossing the beach. They therefore constructed lines of obstacles that would remain submerged for a considerable period either side of high water. These included rows of fixed stakes, hedgehogs and tetrahedra made from girders, and triangular constructions known to the Allies as Element C, to all of which explosive devices had been attached. Such obstructions not only presented a physical barrier but were also capable of disembowelling any landing craft which tried to batter its way through.

The beaches themselves were heavily mined and covered by the fire of machine-guns and artillery weapons housed in concrete bunkers. Where no sea wall existed, high concrete anti-tank walls had been built to block natural exits from the shore. Behind, there were strongpoints containing more guns and automatic weapons, protected by mines, wire entanglements and anti-tank ditches, laid out in depth. Houses and other buildings, specially strengthened, had also been brought into the defensive scheme.

The difficulties facing the Allies were therefore considerable but not insuperable. It was decided that the landings would be made at half tide, when the water was beginning to rise but the lines of obstacles were still exposed. These would be tackled by underwater demolition teams of naval frogmen, who would first disarm the enemy’s explosive devices then clear 50-yard gaps for the passage of the landing craft. Beyond this point, the reduction of the defences became the responsibility of the ground troops.

In the British Army it was generally recognised that the key to the various problems associated with assaulting such long-prepared defensive positions lay in the use of armoured vehicles, just as it had in World War I. In April 1943 Major General P. C. S. Hobart, Commander of 79th Armoured Division, which had been raised the previous October as a conventional armoured formation, was informed that the Army’s specialist tank and assault engineer units would be concentrated under his command with the object of developing techniques and equipment that would be used to spearhead the coming invasion. At the time few of the division’s personnel could have imagined that they were destined to occupy a unique place in the annals of armoured warfare.

Hobart was unquestionably the man for the job. He had begun his career with the Bengal Sappers and Miners and was therefore familiar with assault engineering methods. After World War I he had transferred to the Royal Tank Corps and had commanded the 1st Tank Brigade in 1934. However, as he rose in rank, his innovations and bluntly expressed ideas on the mechanisation of the Army began to make him unpopular with the War Office; nor did it help that he was generally proved right. The problem was that while his insight amounted to something like genius, he had no patience with those who were not similarly gifted. Sometimes, members of his staff would be greatly touched by some personal act of kindness, but most regarded the experience of serving under him as being ‘absolute hell’; those officers who did not instantly and fully comprehend what the General was talking about were left wishing they had never been born. This might have been all very well in its way had not Hobart, who was no respecter of rank, dealt similarly with his superiors. Warned repeatedly by his friends to moderate his behaviour, he expressed genuine surprise that feelings should have been ruffled, and carried on as usual. Known as a fine trainer, in 1938 he was sent to Egypt to form and train the Mobile Division, as the 7th Armoured Division was initially known, and brought it to an outstanding pitch of efficiency and desert worthiness. Unfortunately, he was not to see the results of his work, for following yet another personality clash, this time with the GOC Egypt, he was removed from command and returned home. Early in 1940 he retired from the Army and joined the Home Guard, where his drive and energy quickly earned him promotion to lance corporal. At this point Winston Churchill, recognising the absurdity of losing one of the Royal Armoured Corps’ most outstanding officers at a time of national emergency, recalled him to form and train in succession the 11th and 79th Armoured Divisions.

In Hobart’s opinion not even specialist armour could be expected to produce the required results unless it received direct gunfire support from other tanks. This meant that conventional tanks would have to be landed in the first assault wave, before the beach defences had been neutralised by the specialist armour, a conundrum of apparently chicken-and-egg proportions to which the answer was provided by the DD (Duplex Drive) ‘swimming’ tank. The concept of such an amphibian, kept afloat by a collapsible canvas screen attached to the hull and driven by a screw which drew its power from the main engine, had been pioneered by Mr Nicholas Straussler during the inter-war years; the idea being that once the vehicle had reached the shoreline the buoyancy screen would be lowered and the normal drive engaged, enabling it to perform as a normal gun tank. Successful trials had already been carried out with the Valentine and the Stuart, but the choice for the Normandy landings fell on the Sherman because of its superior firepower. Hobart envisaged that, initially at least, the DDs would provide fire support from the shallows until the specialist armour had produced sufficient elbow room, then fight as the situation warranted. Among those units trained by 79th Armoured Division in the use of the DD were the 4th/7th Dragoon Guards, the 13th/18th Hussars, the 15th/19th Hussars, the Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry, the East Riding Yeomanry, the Canadian 1st Hussars and Fort Garry Horse, and the American 70th, 741st and 743rd Tank Battalions. Various methods of mechanical mineclearing existed, but experience at Alamein had shown that the best results were obtained by flailing, that is beating the ground ahead of a tank with chains attached to a rotating drum powered by the vehicle’s main or auxiliary engine, so detonating any mines in its path. The most successful design was the Sherman Crab, capable of clearing a lane almost ten feet wide at a speed of 1.25 miles per hour; when it was not flailing the Crab could fight as a normal gun tank. The 30th Armoured Brigade, consisting of the 22nd Dragoons, 1st Lothians and Border Horse and the Westminster Dragoons, joined 79th Armoured Division in November 1943 and was immediately equipped with Crabs, which it retained for the rest of the war.

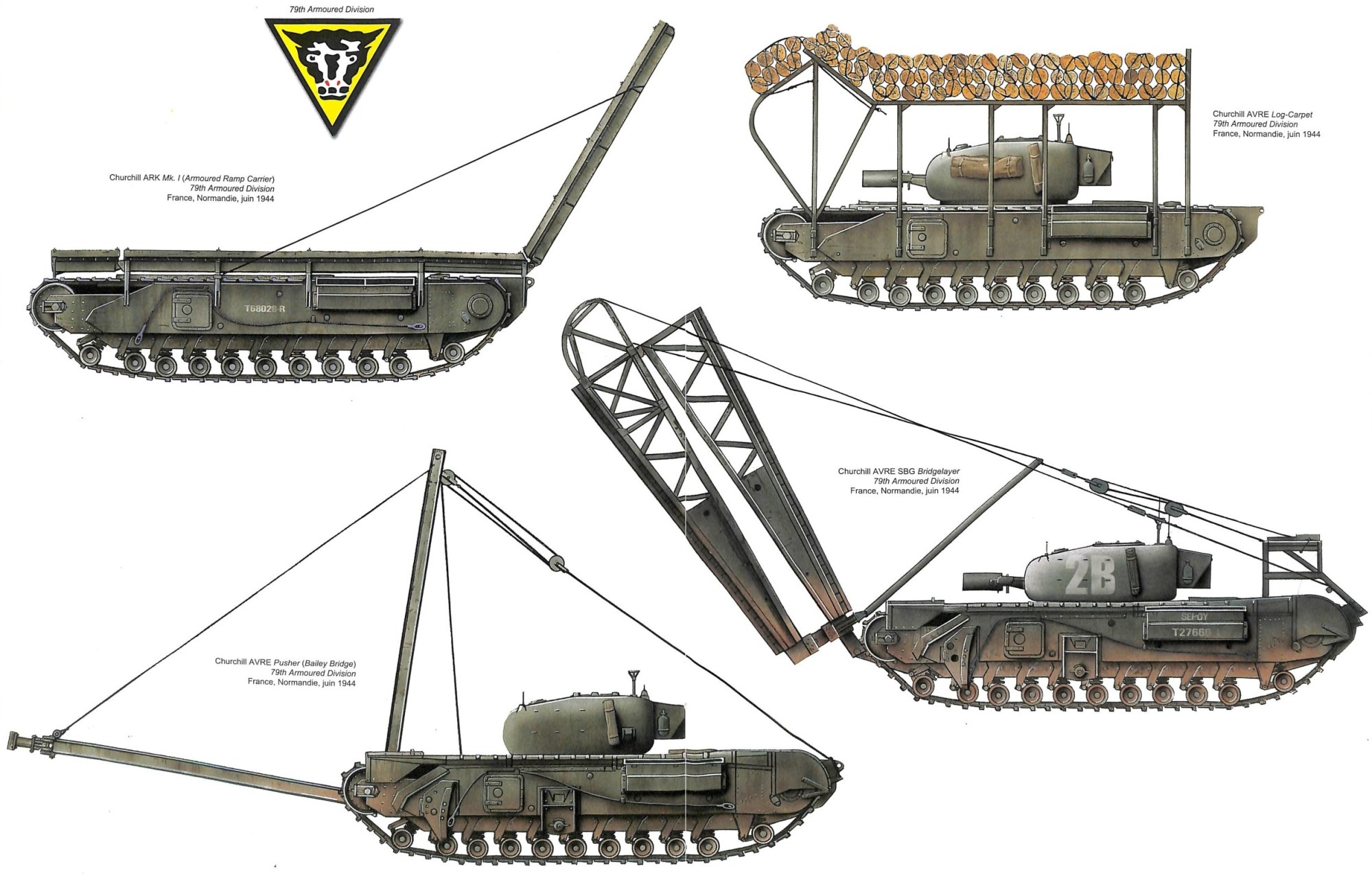

The most versatile vehicle in the division’s armoury was the AVRE (Assault Vehicle Royal Engineers), which had been developed as a direct result of the experience gained in the Dieppe raid. The hull of the Churchill infantry tank was selected as the basis because of its heavy armour, roomy interior and obvious adaptability. The AVRE was fitted with a specially designed turret mounting a 290mm muzzle loading demolition gun, known as a petard, which could throw a 40-pound bomb, designed to crack open concrete fortifications, to a maximum range of 230 yards; reloading was carried out through a sliding hatch above the co-driver’s seat. Standardised external fittings enabled the vehicle to be used in a variety of ways. It could carry a chestnut paling (chespale) fascine, up to eight feet in diameter and fourteen feet wide, that could be dropped into anti-tank ditches, forming a causeway; it could lay an Small Box Girder (SBG) bridge with a 40-ton capacity across gaps of up to 30 feet; it could be fitted with a Bobbin which unrolled a carpet of hessian and metal tubing ahead of the vehicle, so creating a firm track across soft going; it could place ‘Onion’ or ‘Goat’ demolition charges against an obstacle or fortification and fire them by remote control after it had reversed away; it could be used to push Mobile Bailey or Skid Bailey bridges into position; and, on going which was not suited to the Crab, it could be fitted with a plough which brought mines to the surface. The 1st Assault Brigade RE, consisting of the 5th, 6th and 42nd Assault Regiments RE (ARRE), each with an establishment of 60 AVREs and a number of D8 armoured tractors, was formed as part of the division during the summer of 1943.

Naturally, the nature of its work meant that Hobart’s division had to function along the lines of a large plant hire organisation. No two sectors of the German coast defences were exactly alike, and each presented the attacker with its own set of problems. Liaison officers were therefore attached to each of the British and Canadian infantry divisions forming the first wave of Lieutenant General Sir Miles Dempsey’s British Second Army, which formed the left wing of the Allied invasion force. After discussions involving the detailed study of maps, models, the most recent air reconnaissance photographs and intelligence reports, the appropriate assault engineering equipment was allocated and formed into teams which received a similarly detailed briefing on their own specific tasks. These facilities were also offered to Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, commander of the US First Army, which formed the right wing of the Allied assault; apart from the DD battalions mentioned above, they were declined for reasons that have never been satisfactorily explained, with tragic consequences.

On the morning of D Day itself, 6 June 1944, sea conditions were never less than difficult and the fortunes of the DD units varied considerably. Off Utah Beach, the US 70th Tank Battalion launched 30 tanks from its LCTs 3000 yards out and all but one reached the shore safely. In contrast, off Omaha Beach the US 741st Tank Battalion launched 29 tanks 6000 yards out and all but two were swamped and sank. Off Juno, A Squadron of the Canadian 1st Hussars launched ten tanks at between 1500 and 2000 yards, of which seven touched down; the regiment’s B Squadron launched nineteen from 4000 yards, of which fourteen touched down. The day’s most successful performance was put up by the 13th/18th Hussars who launched 34 tanks some 5000 yards off Sword Beach and landed with 31. Elsewhere, conditions were so bad that launching was never contemplated. The US 743rd Tank Battalion landed on Omaha direct from its LCTs; as did, in the British sector, the 4th/7th Dragoon Guards and Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry on Gold and the Fort Garry Horse on Juno, arriving after the armoured assault teams.

The German infantry divisions manning the fortifications of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall contained a high proportion of non-Germans and were regarded by some as being second line troops. Despite this, and the fact that they had been forced to endure air attacks and a mind-numbing naval bombardment, they were prepared to offer the most stubborn and tenacious resistance. They were, however, quite unprepared for the DDs and the wave of specialist armour which was now being disgorged from its LCTs onto the beach, for so good had been the pre-invasion security that the existence of such devices had never been suspected.

For example, while swimming the DD revealed only a few inches of its floatation screen and from a distance resembled a harmless ship’s whaler. Once the vehicle emerged from the shallows, however, the screen dropped to reveal a Sherman spitting fire. On Juno Beach the Canadian infantry were pinned down until A Squadron 1st Hussars came ashore under heavy mortar and shellfire and quickly eliminated strongpoints containing two 75mm guns, one 50mm gun and six machine-guns, after which a large party of the enemy came forward to surrender.

Even the most meticulous of military planners works on the assumption that the natural state of war is chaos, and he allows for as many contingencies as he can. It was, therefore, never envisaged that all of 79th Armoured Division’s breaching teams would be able to clear lanes through the defences, but a sufficient margin of safety had been left for the momentum of the attack to be maintained and enable the assault divisions to start moving inland. It is impossible in these few pages to describe the actions of all the division’s teams, but the following are representative.

On Nan Sector of Juno Beach, where the 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade was to come ashore between Bernières-sur-Mer and St Aubin-sur-Mer, the breaching teams consisted of Crabs manned by B Squadron 22nd Dragoons and the AVREs of 80 Assault Squadron RE (5 ARRE). The DDs had yet to arrive and the teams’ LCTs, also behind schedule, touched down on the rising tide. With the area of exposed beach shrinking steadily and becoming crowded with infantry, No 1 Team’s leading Crab flailed up to the sea wall against which an SBG AVRE laid its bridge. Unfortunately, the first AVRE to surmount this struck a mine a little way further on and was immobilised, blocking the intended exit. Nearby, however, a section of the sea wall had been partially blown down by the preparatory bombardment and two Crabs not only succeeded in flailing their way up to the gap but also scrambled over it and reached the lateral road beyond, which they proceeded to clear. Two fascine AVREs followed and dropped their bundles into the anti-tank ditch beyond. Later, the damaged AVRE was pushed aside by a bulldozer, the driver of which was almost immediately killed by a mine, and the gap through the minefield was completed by hand, creating a second exit.

Because of congestion in the approaches to the beach, No 2 Team’s LCTs touched down some 300 yards east of their intended target. As the AVREs emerged they were immediately engaged by a 50mm anti-tank gun firing from the west. The SBG AVRE was knocked out and another AVRE commander was killed before the remainder silenced the emplacement with their petards. The sea wall, 12 feet high, was only 50 yards away and the Crabs flailed a lane up to it. At this point the loss of the SBG was keenly felt, for although the AVREs damaged the wall with their petards in an attempt to bring it down, they failed to make a wide enough gap and the crater created was too soft and steep for the passage of vehicles. By now the infantry had worked their way forward and drew the team commander’s attention to a beach ramp blocked by Element C, which was blown apart by petard fire. The Crabs then flailed the ramp and an AVRE dropped a fascine into the anti-tank ditch, completing the exit.

No 3 Team had a much easier time, despite the fact that one of its LCTs was hit and barely managed to reach the shore. The Crabs flailed a lane to the sea wall, the SBG bridge was positioned and the Crabs crossed it to continue flailing a route through the dunes as far as the lateral road. No 4 Team, on the other hand, was dogged by bad luck. The LCTs came in 150 yards east of their objective, close to the high tide line and in an area where the depth of water varied considerably. An incoming landing craft collided with an SBG AVRE as it disembarked, forcing the crew of the latter to abandon the vehicle; so close were they to the enemy that three were killed and one wounded by sniper fire and grenades. The team’s Crabs turned west and flailed a lane to No 3 Team’s exit. An AVRE also unrolled its bobbin carpet over an area of soft sand but this was quickly torn apart by the passage of tracked vehicles.

Pending the arrival of the DDs, the infantry had to rely on the Crabs and AVREs to assist them in dealing with those of the defences which were still holding out. ‘A pillbox on the cliff fell to petard fire and houses belching forth streams of mortar bombs and small arms fire were silenced by 75mm and petard fire,’ recorded the divisional historian. As the accuracy of the petard declined beyond 80 yards, most of these engagements took place at close quarters. The bomb itself, known as The Flying Dustbin, was visible throughout its flight and its effect was devastating, bringing whole sections of house down in a thunder of collapsing brickwork and splintering timber; needless to say, very few hits were required to bring the defenders out into the open.

To the east, the breaching teams on Queen Sector of Sword Beach, where the British 8th Infantry Brigade was coming ashore at Lion-sur-Mer, consisted of A Squadron 22nd Dragoons and 77 and 79 Assault Squadrons RE (5 ARRE). On the right No 1 Team beached at a point overlooked by high sand dunes. In the face of fierce fire, the Crabs flailed up the beach and over the dunes, one commander killing two snipers with a grenade thrown from the turret. The leading AVRE, commanded by Sergeant Kilvert, was hit as it emerged from the LCT and drowned in the shallows. Undeterred, Kilvert and his crew grabbed their personal weapons and made their way across the beach to storm a fortified farmhouse and rout an enemy patrol, later handing over their prisoners to the infantry. The team’s remaining AVREs assisted the Crabs in completing a route inland then set off to assist 48 Royal Marine Commando in the capture of Lion.

No 2 Team lay off the beach until the DDs of 13th/18th Hussars had touched down, and in the process drifted west of No 1 Team. The first Crab to disembark, commanded by Sergeant Smyth, immediately charged and crushed the 75mm anti-tank gun that had opened fire on No 1 Team. The Crabs then cleared a lane across the beach until one blew a track on a mine. It was bypassed and an SBG bridge was dropped across the wrecked gunpit, completing the exit. After this, the team’s AVREs also headed for Lion.

No 3 Team’s Crabs completed one lane, along which a Bobbin AVRE unrolled its carpet; the vehicle then struck a mine and, having also been hit by anti-tank fire, was drowned by the rising tide. A second lane was then flailed, at the end of which an SBG bridge was laid to provide an exit from the beach. No 4 Team’s LCT became the target of a heavy calibre gun and was hit repeatedly. The leading Crab got ashore safely but the second was hit while on the ramp and nothing could get past. When more hits caused explosions aboard the craft, killing the sector’s senior engineer officer, it was forced to withdraw and sail back to England. When the team’s solitary Crab had part of its jib shot away by anti-tank fire, its commander, Lieutenant R. S. Robertson, jettisoned the rest and fought as a gun tank.

As more troops and their supporting armour arrived the battle moved inland while the Crabs continued to flail the beach and the AVREs set about the task of recovering vehicle casualties and assisted in removing beach obstacles. The 79th Armoured Division’s breaching teams had employed 50 Crabs and 120 AVREs, of which 12 and 22 respectively had been knocked out; casualties amounted to a total of 169 killed, wounded and missing, which, given the nature of the task which had been set, was astonishing. By midnight on 6 June, 57,000 American and 75,000 British and Canadian troops had been put ashore; and on the British sector alone 950 fighting vehicles, 5000 wheeled vehicles, 240 field guns, 280 anti-tank guns and 4000 tons of stores had been landed.