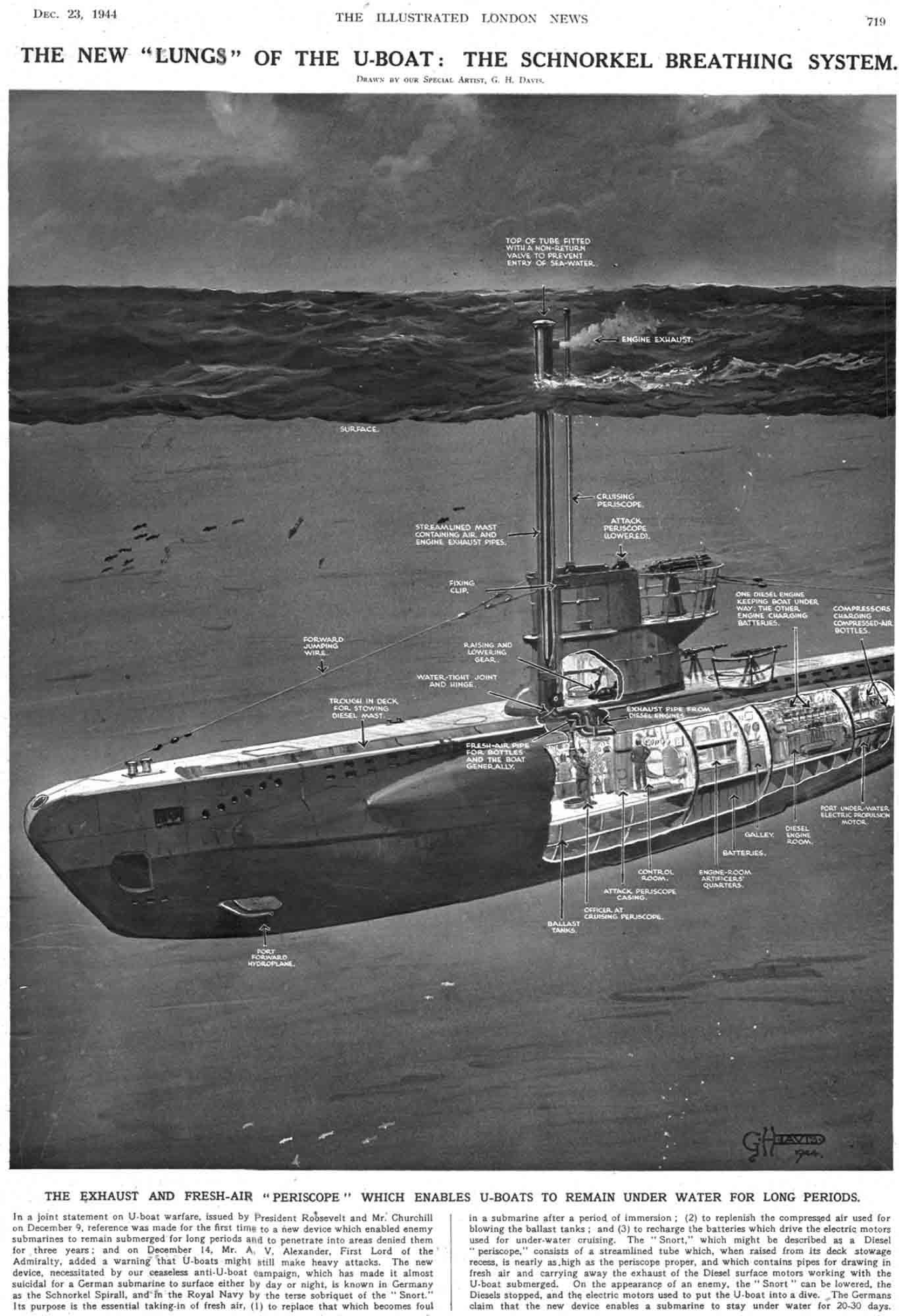

The Illustrated London News, 23 December 1944. Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Franklin D Roosevelt jointly announced to the public on 9 December that German U-boats were now equipped with a device that allowed them to remain submerged. Five days later First Lord of the Admiralty A V Alexander followed up with a public warning that with the appearance of this new device heavy losses should be expected by the public. The day after this illustration was published the snorkel and Alberich-equipped U-486 (VIIC) sunk the SS Leopoldville outside Cherbourg Harbour despite it having a Royal Navy escort, causing a significant loss of life among the US 66th Infantry Division being sent as reinforcements to the Western Front.

The snorkel was treated as a ‘secret’ development by the Kriegsmarine when it was introduced. Allied intelligence certainly intercepted wireless traffic about its existence through Ultra intercepts. However, it appears that the best information came from captured German crewmen picked up after their U-boat was sunk or scuttled.

The British Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence Division’s C.B. 04051 (103) Interrogation of U-Boat Survivors, Cumulative Edition, June 1944 was the first known assessment of the German snorkel. The document revealed that the equipment as well as its basic technical schematics were known to the British at the very start of the Normandy invasion. While this document was descriptive, it did not contain any analysis of the snorkel’s operational or tactical potential as U-boat tactics had not yet evolved. Consequently, the report did not assess any impacts to ongoing Royal Navy Escort or Support Group tactical responses during a U-boat hunt.

This information acquired by British intelligence was accurate. It is clear that by June they had gained knowledge of the Type II non-flange mast as well as the replacement of the pulley system with a hydraulic piston lift. Both design improvements were starting to be fielded broadly across the U-boat fleet, as in the case of U-480, which received a second snorkel installation that summer, upgrading from the Type I to the Type II. The Admiralty report understood that the snorkel was intended for charging, but clearly did not opine the consequences of a non-existent U-boat profile on their detection gear, or the possibility that U-boats could remain submerged for almost their entire patrol. In November British forces that occupied the former German U-boat base at Salamis, Greece, found technical renderings of the Type II snorkel mast installation for Type VIICs, the first such technical documents of their kind obtained by Allied intelligence.

Four months later, US Naval Intelligence observed the stark drop off of actionable intelligence, defined by immediate, readable Ultra intercepts or HF/DF map plots that allowed them to ‘fix’ a U-boat’s location. The report noted the decrease in wireless transmissions and change in Enigma keys, as well as the atmospheric conditions that impacted reception in the North Atlantic. These observations prompted OP-20-G to publish a memorandum notifying US Naval leadership about the impact of these developments to anti-U-boat operations. What the report did not mention was the fact that a number of the intelligence impacts were caused by the introduction of the snorkel, suggesting that OP-20-G did not fully comprehend the correlation. A contributing factor to the lack of understanding was that most snorkel-fitted U-boats were being employed almost exclusively around the coastal regions of the British Isles and not in the convoy lanes of the North Atlantic.

A few statements of note in the 24 November 1944 report are of interest. ‘The problem of fixing U-boats in the Atlantic has become more difficult and will probably continue so …’ for the following reasons: ‘Approximately 90% of the D/F cases have involved U-boat transmissions of the ration of 30 seconds or less. Such short transmissions make it difficult to obtain any large number of high quality bearings.’; ‘the use of Norddeich Off Frequencies has become more general for all types of transmissions. It has been our experience that fewer bearings are obtained on all frequency transmissions of short or medium duration, thereby resulting in less accurate fixes’; ‘U-boats have been maintaining a rigid condition of radio silence. We have noted U-boats on patrol in various areas in the North Atlantic for periods as long as 30 or 40 days without making a single radio transmission’; and ‘ionospheric disturbances, in the North Atlantic in the winter have a detrimental effect upon D/F fixing’.

This resulted in the conclusion by OP-20-G that ‘the accurate locating of U-boats by means of Ultra information has progressively become more and more difficult’.

The OP-20-G memorandum balanced the fact that the dramatic reduction in reliable U-boat position signals was assessed as not impacting operations too significantly given the fact that few U-boats were operating in the mid-Atlantic. The report assumed that if traditional Wolfpack tactics were reinstituted in the spring of 1945 then a natural increase of signals would result in a resumption of accurate U-boat position information. Like the Admiralty report of June, this US Navy intelligence assessment failed to appreciate the paradigm shift introduced by the snorkel.

Overnight the snorkel rendered Allied radar detection almost ineffective and significantly reduced the value of Ultra in fixing U-boats for hunter-killer groups. Yet, a review of US and British intelligence reports revealed that it took both countries about six months to appreciate the snorkel’s impact on their anti-U-boat operations and implement effective countermeasures.

This was revealed by Ladislas Farago, who served as the Chief of Research and Planning in the US Navy’s Special Warfare Branch (OP-16-Z) during the Second World War. Writing after the war, he offered how unprepared the Western Allies were in the face of snorkel-equipped U-boats. The US Tenth Fleet was organised in May 1943 at the very height of the North Atlantic convoy battles as the first anti-submarine command. Its mission was to find, fix, and destroy German U-boats. To this end, its supporting missions included the protection of coastal merchant shipping, the centralisation of control and routing of convoys, and the co-ordination and supervision of all US Navy anti-submarine warfare training, anti-submarine intelligence, and co-ordination with the Allied nations. The Tenth Fleet had no organic naval vessels. Its commander, Admiral Ernest King, used Commander-in-Chief Atlantic’s (CINCLANT) vessels operationally, and CINCLANT issued operational orders to escort groups originating in the United States. The Tenth Fleet was also responsible for the organisation and operational control of hunter-killer groups in the Atlantic.

The Tenth Fleet was ‘misled in its appreciation of the snorkel by reports that tended to emphasise the deficiencies of the device’, according to Farago. Interrogations of German U-boat prisoners early in 1944 who had participated in the first snorkel trials and training in the Baltic spoke despairingly of the device. At this time no U-boat had conducted an operational cruise and not even the German U-boat command understood the device’s full potential. OP-16-Z produced a number of intelligence broadcasts that disparaged the device through the Tenth Fleet. By the summer of 1944 the Tenth Fleet dismissed the snorkel as a viable technological solution for the U-boat. This assessment changed by the late summer and early autumn of 1944 with the approach of U-518 (IXC) off North Carolina in August, followed by others off Canada (see Chapter 9). U-518 sank the SS George Ade, 100 miles from the US East Coast – the first American-flagged ship sunk by a snorkel-equipped U-boat. All Tenth Fleet efforts to hunt down this U-boat failed, leaving it concerned.

The Allies had no tactics or technology to counter the new threat, which was the responsibility of the US Navy’s Tenth Fleet. Farago noted in the early 1960s:

In a very real sense, then, the snorkel thus succeeded in doing exactly what Doenitz hoped it would accomplish: it provided effective protection from the U-boats’ most dangerous foe, the planes of the escort carrier groups. The protection was so effective, indeed, that from September, 1944, through March, 1945, the escort carrier groups managed to sink but a single U-boat, and a non-snorkeller at that, although they accounted for forty-six U-boats during the prior sixteen months.

The Allies devised a simple division of labour in terms of counter-U-boat operations from 1942 onward. The US Navy’s hunter-killer groups were given the responsibility for the central Atlantic and US East Coast, while the British and Canadian air and surface forces were responsible for their respective coastal regions as well as the North Atlantic. This generally placed the burden of counter-U-boat operations on the US Navy from 1942 until early 1944, when U-boats were non-snorkel equipped and operated in Wolfpacks. Once the snorkel was introduced the burden of anti-U-boat operations shifted to the British and Canadian forces through to the end of the war. This included the development of new tactics. It is made clear in reviewing available primary documents that by the end of the war the British and Canadian Royal Navies appreciated the fact that they were fighting a very different U-boat foe, and adapted accordingly. The US Navy and US Coast Guard, however, did not have that same appreciation due to a lack of operational experience against snorkel-equipped U-boats.

Allied Air Operations

In order to destroy a U-boat, it had to be located. By the spring of 1944 location and destruction was predominately carried out by radar-equipped Allied aircraft. The British Air Ministry published ORS/CC Report Nr. 325 on 5 January 1945 titled Operational Experience Against U-Boats Fitted with Snorkel, which summarised the negative impact the snorkel had on Allied air operations against U-boats during the previous six months. The report began: ‘Throughout the past few months the German U-boat fleet have been fitted with a “Snorkel” pipe, about 16’ in diameter and showing some 2–3 feet above the water, through which the air for the Diesels can be sucked in and the exhaust expelled. The consistent use of this device has very considerably reduced the efficiency of [aircraft] detection of U-boats – probably by a factor of about 10, and produced a return to close-in submarine warfare.’

Based on past operational results the following ‘recommendations and statements of fact are considered to follow fairly definitely from the scanty data on operations:’

1. Snorkels are usually seen by their wake and ‘smoke’, this ‘smoke’ is however only produced on some occasions, much more frequent in winter. Theoretical investigation in progress may enable this effect to be predicted. The average citing ranges are average ‘smoke’ 7 miles, (two cases of 20 miles!), wake 4½ miles, snorkel itself about 1 mile.

2. An improvement in efficiency of two- or three-fold could be obtained by use of binoculars throughout.

3. Very little use has in fact been made of binoculars, even for recognition.

4. The operational range of detection on a ASV Mark V (4 miles) is about one third of the operational range on surfaced boats (13 miles), but

5. Radar efficiency is very low and sees more than Force 3 – because of the sea returns.

6. The proportion of snorkel U-boats seen snorkelling and subsequently attacked while visible, or less than 15 seconds dived, amounts to 70% of attacks.

7. Hence the depth charge setting for snorkels should be that proper to ‘snorkel depth’ itself.

8. The sighting range in Leigh-Lights at night is so low (about 400 yards media) that visual bombing holds out little hope. Radar bombing and or homing weapons will be essential.

It was noted in the study that U-boats could clearly be identified through the wakes left by the periscope or snorkel. In the last several months snorkels could be identified seven times greater through the ‘smoke’ trail. This ‘smoke’ was probably vapour caused by a snorkel riding too high out of the water, exposing its exhaust vent. However, the British assessment identified that the smoke, which was usually described as grey in colour, was ‘presumably largely water mist that became clearly visible and much more frequent in cold weather’. The results up to November, according to the assessment, ‘show so low a proportion of ‘smoking snorkels’ (9 out of 22 = 40 per cent) that this phenomenon must be due to some special weather conditions, more frequent in winter than summer’. It was made apparent by the study that the British pilots were not utilising binoculars during their air patrols and that a periscope or snorkel that was not smoking could be identified by binoculars at about 4.5-mile range, while the naked eye could only identify it at a range of 1.9 miles. Despite this fact, the study stated that very few periscopes or snorkels were in fact either first sighted or even recognised using binoculars. Even when air patrols used binoculars, they assessed that periscopes were identified only 16 per cent of the time, while snorkels only 33 per cent. By binocular ‘recognition’ it was meant ‘to identify the vague phenomenon: wakes, smoke, odd looking waves, etc. which are usually first seen’. The study also looked at the rate at which binoculars could identify a periscope or snorkel when radar contact had provided a rough bearing an exact range. It was determined that a binocular was used to confirm a radar bearing 19 per cent of the time. All this led to the conclusion that ‘there is room for considerable improvement in the use of binoculars, both regular scanning by lookouts detailed for the purpose whenever the neck disability is more than 5 miles and for recognition of radar blips. The second point could be met by the second pilots always keeping a pair of binoculars ready focused.’ What this assessment did not consider was the fact that U-boats predominately snorkelled at night as directed by BdU [Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote], limiting the effectiveness of visual identification even further.

A separate detailed analysis was conducted on daylight attacks against U-boats by aircraft during the period June to December 1944. This study focused on U-boats that submerged once they were attacked on the surface. The report was divided into attacks that occurred when a U-boat had been submerged for less than fifteen seconds, submerged between fifteen and sixty seconds, submerged more than sixty seconds, and were lost while the aircraft was manoeuvring to attack. The study found that whether the U-boat was identified operating with just a periscope or snorkel separately, or the U-boat was identified operating both simultaneously, it was impossible to obtain a kill once the vessel began to submerge. The kill rate per attack when the snorkel and/or periscope were still visible was only at 17 per cent. This was 50 per cent less than the 43 per cent kill rate for a completely surfaced U-boat. The study went on to state ‘the number of snorkel sightings leading to targets visible, partly visible or dived less than 15 seconds (41% of sightings, 74% of attacks) is so high that the DC’s against snorkels should have the depth setting proper to the boat actually snorkelling’. This data does support that the U-boat dipole mounted on the snorkel mast was effective in identifying attacking aircraft, giving U-boats the advantage of diving before an air attack commenced. A fifteen-second advantage was enough to gain survivability against an air attack regardless of how far out the aircraft identified the snorkelling U-boat. The realisation that snorkel ‘smoke’ was a marked advantage caused British Coastal Command to issue a memo that declared this study was only permitted to be circulated among those engaged in ‘Air Anti-U-boat Warfare’. Not even the Royal Navy was notified of this observation in order to maintain strict secrecy over this operational advantage. Given that this memo was issued on 22 March 1945, at the end of winter, it probably contributed little to the anti-U-boat effort. However, it does show how seriously the snorkel altered the balance sheet against Allied aircraft.

One effective Allied aircraft tactic against snorkel-equipped U-boats introduced was the use of sonobuoys. U-boat commanders noted in their short reports to BdU that Allied aircraft dropped sonobuoys in areas where their snorkels were presumably seen to alert other aircraft or anti-submarine groups to the U-boat’s diving points. All U-boats were warned of this tactic on 15 February by BdU, suggesting it was a recently employed tactic. There were two types of sonobuoys, one for listening and one for HF/DF. The HF/DF buoy was less effective as snorkel-equipped U-boats rarely transmitted wireless signals. It was the direction-finding buoy that was used with effect during the last six months of the war against the snorkel-equipped U-boat.

Sonobuoys were originally intended to be dropped manually from blimps. Parachutes were added when the decision to deploy them from manoeuvring aircraft was made. They were equipped with a stored, self-erecting antenna. The first operational passive broadband sonobuoy was known as AN/CRT-1. The operational frequency of the AN/CRT-1 was 300Hz to 8kHz, which was within the audible range of the human ear. The operator had to make real-time decisions based on his ability to distinguish various underwater sounds. The problem was that in shallow water the operator had to contend with a host of other noises caused by waves, currents and density layers, making identification of a U-boat operating on electric motors or even drifting with engines off problematic. An improved version, the AN/CRT-1A, also known as the Expendable Radio Sonobuoy (ERSB), had an increased frequency band of 100Hz to 10 kHz and lighter weight (12.7lb).

The improved sonobuoy contained enough battery power for four hours of continuous operation. It was not until June 1944 that these new sonobuoys were being employed by US aircraft squadrons operating in the central Atlantic. It was not until the autumn of 1944 that a single British aircraft squadron received the device for employment.

As an approximation, an aircraft equipped with eight sonobuoys could hold contact with a U-boat for sixty to ninety minutes, and if equipped with twelve, for as long as three hours. This was ample time to vector in a surface hunter-killer group or squadron. The drawback was that calm water was required to achieve these contact times.

The British also took a careful look at operational and practice data recording radar returns against the snorkel. The data the British collected was identified by their own intelligence analysts as ‘scanty’. The S-Band equipment, while operational, could not be compared effectively with the X-Band, which was not yet operational. However, in looking at the MK.V Liberator it was noted that the operational range to identify a periscope or snorkel was 4.7 miles compared with the average of 12.9 miles by day or 14.3 miles by night for this specific equipment on surfaced U-boats. It was thought that the ratio of a third would appear promising until it was realised that this fact implied the majority of these contacts would appear inside the ‘sea returns’ and thus be almost impossible to recognise by sight. The study predicted that in a calm sea the MK.V Liberator had a ratio of 10:1 to identify the snorkel or periscope, while the MK.III Wellington’s ratio was 6:1. In moderate seas the ratios were respectively 50:1 and 30:1. In rough seas it was considered next to impossible to make a radar contact. The conclusion was that the S-Band’s operational range against snorkels ‘appears to be about one-third of that on surfaced U-boats’. In addition ‘detection of snorkel radar in seas of Force 3 or higher is much more difficult than in calmer seas’.

While the above data was based on daylight attacks, a sobering assessment of night-time attacks was also made. The study concluded: ‘The sighting range of the snorkel at night is so low that the technique of attack hitherto used, i.e. radar contact – visual sighting – release of bombs by visual judgment – holds out little hope of success. It is suggested that either radar bomb sites or homing weapons or both are essential.’ This observation is interesting when compared with the procedures outlined to German U-boats by BdU that snorkelling should be carried out at night. This meant that if proper guidance was followed then a snorkel-equipped U-boat’s survivability against aerial identification and attack was very high. No calculations were made by the British in their report between snorkels camouflaged with anti-radar matting and those without. The process of covering snorkel masts with the Wesch anti-radar matting became commonplace in the autumn of 1944 and served to reduce the ability of Allied radar detection even further than already indicated in the above assessment.

The British knew the U-boats were there but were now unable to easily locate them or even effectively employ their aircraft and radar technology against them. The study noted that ‘of the conclusions drawn some are practically certain; others are open to some doubt as based on small numbers. It is however, considered that, in view of the urgency of the snorkel problem, these probable conclusions should also be drawn.’ Indeed, there was a snorkel problem. Six months into this problem the Western Allies were still struggling to identify probable countermeasures against an enemy that they thought was defeated in May 1943, but that had now returned with a vengeance.

Given the negative impact that the snorkel had on British air-based antisubmarine efforts, a series of meetings were convened starting on 22 November 1944 that were intended to address the issue. Meetings followed on 15 December, 19 January 1945, 29 January and 13 March to identify solutions to the troubling snorkel trend. These meetings were held in Room 71/II at Whitehall in the Air Ministry and were chaired by Sir Robert Renwick Bt, who looked for updates from Air Commodore H Leedham, CB, OBE, as the DCD (Director of Communications Development), and Dr A C B Lovell, as the TRE, on ‘actions taken by the DCD and TRE (Telecommunications Research Establishment) to provide anti-Schnorkel measures …’ In the first meeting in November it was stated that ‘methods that could be introduced into existing equipment which it was anticipated would give some 20%–25% increase in the ratio of the snorkel responses as against those of sea returns’. In addition, Commodore Leedham believed that either X-Band or K-Band could be used but at least another month of experiments was required. It was confirmed in December that ongoing trials suggested that modifications to both the Wellington and Warwick systems would allow them to better pick up smaller targets. X-Band trials were still ongoing. It was also recommended that American detection systems be included in the testing programme.

In the 19 January meeting it was expressed that significant delays caused by wrongly specified equipment had prevented Coastal Command from equipping their aircraft with the new detection system modifications. K-Band was given the highest priority and X-Band results were promising. By 29 January, Coastal Command aircraft were finally receiving modifications to their radar sets that would allow for better detection of smaller targets. Interestingly, it was noted that the tests being performed off Llandudno, North Wales, in the Irish Sea against British submarine test targets had to stop due to the presence of actual U-boats in the testing area. The first X-Band-equipped Warwick Mk V aircraft were expected to be delivered in late March or early April.

The Air Ministry wanted to increase their chances of a successful attack against a snorkel-equipped U-boat by 20 per cent. Most of their recommendations, however, were not implemented until the spring of 1945. The US was not involved in these meetings, primarily as they were not directly engaged in the snorkel war to any great extent. British findings were to be made available to the US primarily because it was thought they would ‘interest them’.

BdU issued new guidance on 3 March 1945 to their U-boats based on changes introduced by British Coastal Command air patrols. Specifically, Message No. 226C reminded U-boats to maintain depth discipline when snorkelling and avoid being observed. Seven days later, on 10 March 1945, a follow-on message was sent, followed by further guidance to maintain a low snorkel profile in calm surface conditions embodied in Message No. 228B.

What BdU did not calculate was that with the coming of spring, North Atlantic storms gave way to calmer water, as noted by the reference in Message No. 228B of a sea state 1. This increased the potential of a U-boat’s identification through a raised snorkel or periscope by Allied radar or visual recognition.