The Second Sudan War, 1896-8

Despite their tactical reverses, the dervishes followed up the British withdrawal from the Sudan. On the Nile sector their northwards advance was checked at Ginnis on 30 December 1885, the battle being otherwise remarkable in that it was the last occasion on which British infantry went into action in their traditional scarlet. Under British officers, the Egyptian Army was reformed, the men being given regular pay, decent conditions of service, the prospect of promotion and thorough training. Skirmishing continued along the frontier, escalating to a seven-hour pitched battle at Toski on 3 August 1889 in which the dervishes were decisively defeated with 1000 killed, a quarter of their strength, including one of their most notable commanders, the Emir Wad-el-Najumi.

In 1896 it was decided that the Sudan would be reconquered. This decision was not taken for the humanitarian cause of rescuing the Sudanese from the Khalifa’s barbaric oppression, but for altogether more pragmatic reasons. The Italians, for example, had been seriously defeated by the Abyssinians at Adowa in 1892. The event damaged the prestige of all the colonial powers and there was a need to restore this. Even more pressing was the interest which other great powers, notably France, were showing in establishing control of the upper reaches of the Nile.

The Sirdar or Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Army was General Horatio Herbert Kitchener, who had been appointed to the post in 1892. He had performed intelligence duties during the Gordon Relief Expedition and considered the British withdrawal to have been a national disgrace. He had later commanded at Suakin. He was not a notable tactician but he was an expert in logistics, the very quality required for a campaign that would be conducted over such vast distances.

Egypt, goes the saying, is the gift of the Nile and so, largely, is the Sudan. The contribution made by Gordon’s little gunboats during the 1884-5 war was such that Kitchener decided his own advance would have continuous gunboat support. When the new war started he had at his disposal four old stern-wheel gunboats, named after battles in the earlier war (Tamai, El Teb, Abu Klea and Metemmeh), all armed with one 12-pounder gun and two Maxim-Nordenfeldt machine guns. From 1896 onwards these were joined by three more stern-wheelers, Fateh, Naser and Zafir, armed with one quick-firing 12-pounder, two 6-pounders and four Maxim machine guns. In 1898 the flotilla was joined by three twin screw gunboats, Sultan, Melik and Sheikh, armed with one quick-firing 12-pounder, two Nordenfeldts, one howitzer and four Maxim machine guns. These last were built by Thornycroft and Company at Chiswick and shipped out to Egypt in sections. Some of the craft were fitted with powerful searchlights.

The gunboats’ crews consisted of British, Egyptian and Sudanese service personnel and civilians. In command were junior officers drawn from the Royal Navy and the Royal Engineers most of whom would achieve distinction if they had not already done so. The flotilla commander, and also captain of the Zafir, was Commander Colin Keppel whom we have already met during the final stages of the Gordon Relief Expedition. Commanding the Sultan was Lieutenant Walter Cowan who, in 1895, had captured a rebel standard during a punitive expedition in East Africa; a born fighter, he will appear again in these pages and was still fighting in his seventies. Lieutenant David Beatty, commanding the Fateh, would command the battlecruiser fleet at the Battle of Jutland and go on to command the Grand Fleet itself. Lieutenant the Hon. Horace Hood, commander of the Naser, was to lose his life commanding the Third Battlecruiser Squadron at Jutland. Captain W. S. ‘Monkey’ Gordon, RE, was a nephew of General Charles Gordon and thus had a personal stake in the successful outcome of the campaign.

Curiously, when the Second Sudan War commenced, both Kitchener and the Khalifa had decided that the decisive battle would be fought near Omdurman, across the river from Khartoum, where the dervishes had made their capital. Both were aware that in desert warfare a victorious army becomes progressively weaker the further it advances from its sources of supply. The Khalifa’s plan, therefore, was to offer only token resistance to the Anglo-Egyptian advance, drawing Kitchener further and further into the wilderness just as Hicks had been drawn to destruction in 1883. Kitchener, however, intended harnessing the most modern means of transport available, not only to keep his troops supplied but also to reinforce them with fresh British brigades at the critical moment so that when the battle was fought he would have twice the strength with which he had begun the campaign.

One by one the dervish outposts fell after varying degrees of fighting, these local successes doing much to raise the morale of the Egyptians. When Dongola was captured Kitchener took the decision which was to win him the campaign. This was nothing less than to build a railway through the 235 miles of arid and empty desert between Wadi Halfa and Abu Hamed, cutting across the northern arc of the Great Bend. Many doubts were expressed about the idea, for without water, steam locomotives were as helpless as men in the desert. Fortunately, Royal Engineer survey parties located suitable sources of water 77 and 126 miles out from Wadi Halfa. Construction commenced on 1 January 1897 and proceeded at an average rate of one mile per day. Simultaneously, Kitchener sent a diversionary force along the route taken by Stewart’s Desert Column in 1885, hoping to convince the enemy that this was his chosen axis of advance.

During the early stages of the campaign the attack against the dervish positions at Hafir on 19 September 1896 received gunfire support from Tamai, Abu Klea and Metemmeh, which also sank an enemy steamer. During this action Abu Klea was extremely lucky in that a shell penetrated her magazine but failed to explode. On the 22nd the flotilla was joined by the Zafir and El Teb. The next day Dongola fell to a combined attack by the army and the gunboats.

The advance was renewed when the level of the Nile rose again the following year. On 5 August the flotilla commenced its ascent of the Fourth Cataract, led by Tamai. Some 300 local tribesmen had been recruited to assist by hauling on ropes from both banks and, with her stern-wheel thrashing at full power, the gunboat succeeded in climbing half the slope of water. The pull on the ropes, however, was uneven and her head began to pay off. The immense pressure of water would have capsized her had not the ropes been released in the nick of time. Bobbing like a cork, she was carried downstream.

Another 400 tribesmen were recruited and that afternoon El Teb tried the ascent. The same thing happened, but this time the gunboat capsized, flinging Lieutenant Beatty and his crew into the rushing water. All save three were picked up downstream by the Tamai. One man was known to have drowned but the fate of two more remained uncertain. Keel uppermost, El Teb floated down the river until she became trapped between two rocks. A party reached the wreck to see whether she could be salvaged and was about to leave when knocking was heard within the hull. Tools were brought and a plate removed from the keel. Somewhat battered by their ordeal and blinking, the two missing men, an engineer and a stoker, emerged from total darkness into brilliant sunlight. Raised and repaired over a period of months, El Teb was renamed Hafir to change her luck, and took part in the later stages of the campaign.

It was decided to try to ascend the cataract at another point, once the level of the river had risen a little more. The method of hauling was carefully revised and with yet more men on the ropes Metemmeh was successfully brought to the top on 13 August, followed by Tamai the following day, Fateh, Naser and Zafir on the 19th and 20th, and the unarmed steamer Dal on the 23rd. Abu Hamed had already been taken by the army and, to its surprise, Berber was occupied without the need for a fight. On 14 October the Fateh, Naser and Zafir steamed south and engaged the dervish fortifications at Shendi and Metemmeh. During the two-day operation 650 shells and several thousand rounds of Maxim ammunition were fired, inflicting about 500 casualties in return for one man killed and some minor damage.

The rounding of the Great Bend and the capture of Berber were of enormous strategic significance. Those dervish forces in the eastern Sudan found their position untenable and were forced to retire on Omdurman. This provided Kitchener with a second line of supply once the route from Suakin was re-opened. It also enabled completion of the Desert Railway. The line reached Abu Hamed on 31 October and was extended southwards. Along it came the three newest gunboats, the Sheikh, Sultan and Melik. These had been shipped in sections from England to Ismailia on the Suez Canal, then towed along the Sweet Water Canal and the Nile to Wadi Halfa. There, under Captain Gordon’s supervision, the sections were loaded on to railway flats and transported to Abadiya. On arrival, they were launched and assembled by another Royal Engineer officer, Lieutenant George Gorringe, whom we shall encounter again in a later war, commanding a division in Mesopotamia. Lacking heavy lifting gear, Gorringe was forced to improvise, using railway sleepers, rails, ropes and muscle power. During the final fitting-out phase he was joined by Gordon.

On 1 November the Zafir, Naser and Metemmeh again bombarded Shendi and Metemmeh. Joined the next day by Fateh, they continued their raid as far south as Wad-Habeshi. During this foray three men were wounded when a shell struck the Fateh. By now the river had begun to fall and, rather than expose the gunboats to rapids which had appeared at Um Tiur, four miles below the point where it was joined by the Atbara river, a small fortified depot was established for them at Dakhila, just north of the confluence, becoming known as Fort Atbara.

With a growing sense of unease the Khalifa began to realise that he was engaged in a new type of war which he did not really understand. He had never seen a railway but its workings were explained to him and when his spies told him that each day a mountain of supplies reached Kitchener’s army in this way he knew that the Desert Railway had to be destroyed. Although he still believed that the decisive battle would be fought at Omdurman, he despatched 16,000 men under one of his less popular followers, the Emir Mahmud, to execute this important mission. For his part, Mahmud, resenting the fact that the Khalifa seemed to regard him as expendable, declined to do much more than indulge in isolated skirmishes and dug himself trenches within a large zareba which had its back to the dry bed of the Atbara River. During their crossing of the Nile from Metemmeh to Shendi, his troops were badly shot up by the gunboats.

Meanwhile, Kitchener, seeing the critical final phase of the campaign approaching, had obtained two British brigades from the War Office, the first of which joined his army in January 1898. Offensive operations began on 27 March when the Zafir, Naser and Fateh, with troops aboard or in towed boats, attacked and took Shendi. On 8 April Kitchener stormed Mahmud’s zareba on the Atbara, killing 3000 dervishes and taking 2000 prisoners, the latter including Mahmud himself. The Anglo-Egyptian army’s casualties amounted to less that 600. The gunboats were not directly involved in the battle but a landing party under Lieutenant Beatty used rockets to set fire to the zareba, opening the way for the troops’ assault.

The road to Omdurman now lay open but Kitchener was not inclined to advance until the second British brigade had joined him and did not set his troops in motion again until August. On the 28th the flotilla sustained its most serious loss when, near Metemmeh, the Zafir suddenly sprang a serious leak and went down by the head in deep water before she could be run aground. Although no lives were lost, only the Maxim machine guns could be salvaged from the wreck. As no readily identifiable cause has been quoted, sabotage springs to mind as one possibility.

While the army kept pace, the rest of the flotilla passed through the Shabluka Gorge, a place of swirling water and precipitous cliffs covered by several now abandoned dervish forts. Well aware of the gunboats’ potential, the Khalifa increased the number of batteries guarding the river approach to Omdurman and decided to mine the river itself by using two old boilers filled with explosive to be detonated by a pistol, the trigger of which would be pulled by cord from a safe distance. A former officer of the Egyptian Army, who had been a prisoner since the Mahdi’s day, was put in charge of the project. As the first boiler was being lowered into the water the cord snagged, the pistol fired and the reluctant mine warfare expert and his team were blown apart. An emir was ordered to supervise the installation of the second mine. Being a canny man, he allowed water to leak into the explosive, rendering it useless, before sinking the device. The grateful Khalifa rewarded him with a number of presents.

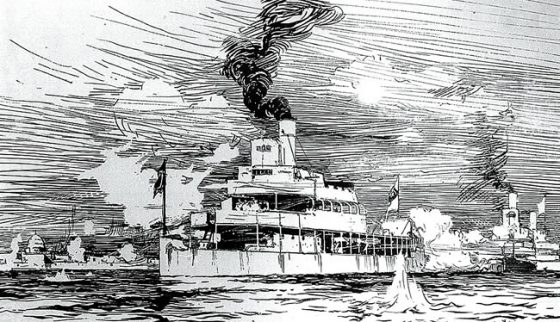

On 1 September the gunboats landed their howitzers to supplement the army’s artillery, then moved up-river to engage the river batteries at Omdurman, Khartoum and on Tuti Island between. Lieutenant Cowan of the Sultan made the dome of the Mahdi’s tomb his special target and punched several holes through it, causing dismay among the superstitious dervishes. Winston Churchill, then a junior officer attached to the 21st Lancers, had a grandstand view of the engagement, of which he has left us the following graphic account:

At about eleven o’clock the gunboats had ascended the Nile, and now engaged the enemy’s batteries on both banks. Throughout the day the loud reports of their guns could be heard, and, looking from our position on the ridge, we could see the white vessels steaming slowly forward against the current, under clouds of black smoke from their furnaces and amid other clouds of white smoke from their artillery. The forts, which mounted nearly fifty guns, replied vigorously; but the British aim was accurate and the fire crushing. The embrasures were smashed to bits and many of the dervish guns dismounted. The rifle trenches which flanked the forts were swept by the Maxim guns. The heavier projectiles, striking the mud walls of the works and houses, dashed red dust high in the air and scattered destruction around. Despite the tenacity and courage of the dervish gunners, they were driven from their defences and took refuge among the streets of the city. The great wall of Omdurman was breached in many places, and a large number of unfortunate non-combatants were killed and wounded.

Seven miles to the north, the army spent the night within a zareba centred on the village of El Egeiga, around which it curved in a half-moon with both flanks resting on the Nile. Outside the zareba lay a bare featureless plain which both sides recognised would be the morrow’s battlefield. Throughout the hours of darkness the gunboats’ searchlights probed the hinterland as a precaution against surprise attack. ‘What is this strange thing?’ asked the Khalifa, pointing to the distant, unblinking orbs. ‘They are looking at us’, he was told by those who understood.

At dawn the Khalifa led out his 60,000-strong army to launch an immediate attack on the zareba. The subsequent battle has sometimes been described as a triumph of firepower over fanatical courage, but that is simplistic. The dervishes had plenty of guns and their field artillery was actually on its way forward when the attack was launched. They also possessed machine guns, and although many of these were obsolete or damaged by rough handling, there were sufficient unscrupulous arms salesmen in the world to satisfy the Khalifa’s needs had he chosen to contact them. The truth was that the dervishes regarded field artillery and machine guns simply as a preparation for the wild charge with sword and stabbing spear, borne forward on a wave of religious fervour.

At 06:25, with the enemy 2700 yards distant and closing rapidly, Kitchener’s artillery opened fire. The gunboats joined in immediately, followed by the Maxim machine guns. At 06:35, with the range down to 2000 yards, volley firing commenced, and within ten minutes the whole of the Anglo-Egyptian line was ablaze. Disregarding their heavy casualties, the dervishes continued to press their attack, but few got closer than 800 yards on the British sector, or 400 yards opposite the slower-firing Egyptians. By 07:30, however, they had had enough and, in their usual way, turned about and walked off.

Elsewhere, matters had not gone according to plan. The Egyptian cavalry, accompanied by a horse artillery battery and the Camel Corps, had been operating outside the zareba and, while withdrawing over the Kerreri Hills, it succeeded in drawing off a large proportion of the dervish army. The slow-moving Camel Corps was soon in difficulty on the broken ground and began to suffer casualties from the enemy riflemen. Burdened with wounded, it was ordered to make for the northern flank of the zareba. With the dervishes in hot pursuit and on the verge of running their quarry to ground, it began to look as though a massacre would take place, but at that moment Captain Gordon’s Melik took a hand. Churchill wrote:

The gunboat arrived on the scene and began suddenly to blaze and flame from Maxim guns, quick-firing guns and rifles. The range was short; the effect tremendous. The terrible machine, floating gracefully on the waters – a beautiful white devil – wreathed itself in smoke. The river slopes of the Kerreri Hills, crowded with the advancing thousands, sprang up into clouds of dust and splinters of rock. The charging dervishes sank down in tangled heaps. The masses in the rear paused, irresolute. It was too hot even for them. The approach of another gunboat completed their discomfiture. The Camel Corps, hurrying along the shore, slipped past the fatal point of interception, and saw safety and the zareba before them.

Somewhat prematurely, Kitchener ordered a general advance. As a result of this an Egyptian brigade came close to being overrun by a dervish counter-attack but was saved by the tactical skill of its commander. The 21st Lancers made their epic but pointless charge, during which Churchill shot his way through the enemy ranks with a privately purchased Mauser automatic pistol. By 11:30 the battle was over. The dervish loss amounted to 9700 killed and perhaps twice that number wounded. Anglo-Egyptian casualties were 48 killed and 428 wounded. Omdurman was occupied during the afternoon. On 4 September it was, fittingly, the Melik which ferried troops to Khartoum for a memorial service for General Gordon, held beside the ruins of the governor general’s palace.

The Khalifa, his power broken, was now a fugitive who would have to be hunted down, but for the moment another matter claimed Kitchener’s attention. On 7 September the Tewfikieh steamed into Omdurman from the south. Her dervish crew, promptly made captive, told a strange tale. The Khalifa had sent them up-river as part of a foraging expedition, but at Fashoda, 600 miles from Omdurman, they had been fired on by black troops commanded by white officers under a strange flag. Having sustained serious casualties, the foraging party had retired some way and sent the Tewfikieh back to Omdurman for further orders. Naturally, news of the presence of another European power on the Upper Nile was far from welcome. Having embarked two infantry battalions, two companies of Cameron Highlanders, an artillery battery and four Maxims aboard the steamer Dal and the gunboats Fateh, Sultan, Naser and Abu Klea, Kitchener set off in person to discover who these intruders might be. On 15 September the foragers’ camp was reached. Rashly, the dervishes, 500 strong, opened fire on the gunboats and were quickly dispersed. Their remaining steamer, the Safieh, tried to escape but, for the second time in her history, a shell burst her boiler.

During the morning of 19 September the gunboats were met by a rowing boat containing a Senegalese sergeant and two men. They handed Kitchener a letter from their commander, a Major Marchand, which confirmed French occupation of the Sudan, offered congratulations to the Sirdar on his victory, and welcomed him to Fashoda in the name of France. Marchand’s force, consisting of eight French officers and NCOs and 120 Senegalese soldiers, was found to be in occupation of the former government post. They had left the Atlantic coast two years earlier and had marched continuously across all manner of terrain before planting the tricolour at Fashoda. They were delighted by Kitchener’s arrival as they had fired off most of their ammunition, had no transport and very little food, and were in touch with no one. Kitchener got on well with Marchand, congratulated him on his remarkable achievement and courteously suggested that settlement of the issues between them was best left to their respective politicians. Faced with so much firepower, Marchand could but agree. Kitchener established one Anglo-Egyptian garrison at Fashoda and two more 60 miles to the south, then, leaving the Sultan and the Abu Klea to support them, he returned to Khartoum. By December the diplomats had reached a conclusion that France had no interest in the area after all. Marchand and his men continued their journey by way of Abyssinia to the French territory of Djibouti, having marched right across Africa.

A period of pacification followed Kitchener’s victory at Omdurman. There were pockets of resistance, notably east of the Blue Nile and in Kordofan province, whence the Khalifa had fled, but most Sudanese had had enough of dervish rule. Control of the major waterways by the gunboat flotilla, latterly commanded by Lieutenant Walter Cowan, was absolute. Often the mere appearance of a gunboat was enough not only to induce the surrender of the dervish garrison of a town, but guarantee a warm welcome from its inhabitants. By the end of the year the last dervish force in the eastern Sudan had been decisively defeated, leaving only the Khalifa and his most ardent followers at large. Finally, on 25 November 1899, he was cornered at Om Dubreikat and, together with his principal emirs, fought to the death.

Of the gunboats which served on the Nile during the period of the dervish wars, two survive. One, the Bordein, it will be recalled, saw much active service during the siege of Khartoum. The second is the Melik, which, after being decommissioned, served as the clubhouse of the Blue Nile Sailing Club until an exceptional flood left her stranded. The Sudan’s Department of Archaeology and Museums is believed to be working on a repair and maintenance plan for both.