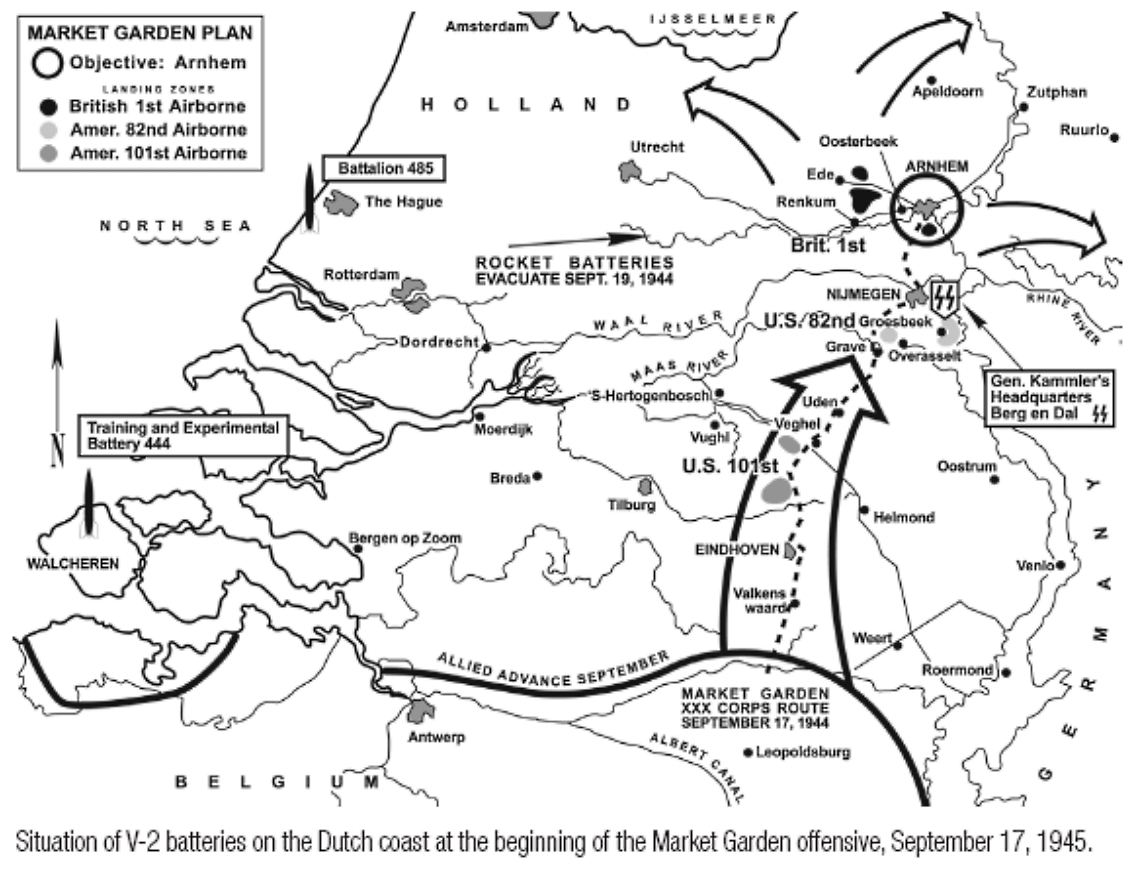

On September 19, 1944, at the beginning of the Allied airborne landings, SS General Kammler ordered the evacuation of all rocket troops from The Hague and Walcheren, for fear they might be cut off. The inhabitants of Wassenaar were able return to their homes after Battalion 485 withdrew from the area under the cover of darkness. The vehicles of the first battery traveled north and arrived at Overveen near Haarlem and then retreated all the way into Germany in Burgsteinfurt, where they were joined later by the second battery. The first battery of 485 set up operations west of the small town of Legden with two firing sites at Beikelort where they launched a total of 21 rockets from September 21 to October 8 against continental targets such as Louvain, Tournai, Maastricht, and Liège. At the beginning of Market Garden, American forces almost nabbed General Kammler at Berg en Dal, so he also moved his headquarters to the German town of Darfeld in Burgsteinfurt for a short time; but after moving again to Ludenscheid on September 21, he soon established a permanent headquarters in Germany, east of Dortmund at Suttrop bei Warstein on October 3.

It is often reported that Kammler’s headquarters was located for a time in the Dutch town of Haaksbergen. In fact, there was no German headquarters of any kind at Haaksbergen. It may have been confusion between the names Haaksbergen and Schaarsbergen. Schaarsbergen was about 20 kilometers from Apeldoorn, and many German barracks were concentrated in this area. Dornberger and Kammler reportedly met on several occasions at a location near Apeldoorn.

In early September of 1944, after their instruction at Köslin, SS Werfer Battery 500 moved into Poland for live firing exercises. The SS rocket troops were brought to the V-2 test range at Heidekraut, where they rapidly received their final training. Crew members were hastily rehearsed in their individual duties. Finally, the test missiles were moved to a remote launching site, fueled, tested, and fired. Beginning on September 13, each platoon launched several missiles, but lack of motorized transport and ground support equipment hampered portions of the training. All new equipment delivered had to be allotted to the operational units on the battlefront. When the exercises concluded on September 19, the V-2 campaign was already underway, and the whole battery, vehicles included, was loaded onto a freight train that departed toward the west. The train arrived in Münster, where everything was off-loaded. From there, the SS 500 drove further to Burgsteinfurt. They moved into a prepared launching site code-named Schandfleck among the tall oak trees just off the main road to Schöppingen near the German town of Heek. The battery fired its first operational V-2 on October 19, but the rocket crashed in a meadow only a few miles from the firing point. During the next two weeks, the SS 500 launched approximately 30 more V-2s, all successfully.

The first battery of Battalion 485 had already been operating in Burgsteinfurt since September 21 and was reported to have launched ten times against Liège over the period of October 4 to October 12. In total there were 27 reported impacts in the surroundings of Liège.

After the third battery of Battalion 485 completed their training at Heidekraut, they were sent into action in mid-October 1944. They joined SS 500 and the first battery of Battalion 485 in the Burgsteinfurt area, driving to a firing location west of the German town of Legden at Beikelort. The battery at that time consisted of only the first and second platoons; the third platoon had been sent to The Hague, which was very unusual, because normally individual platoons were not separated from their batteries. From Beikelort the two platoons fired 35 rockets at Antwerp over the period of October 21 to November 5. The railway siding outside the town of Legden was the main supply point in the area, and on October 9 Allied fighter bombers attacked a V-2 transport train, which was burned out and destroyed. At the beginning of November, the two platoons moved to a new position just outside of Legden near the castle Schloss Egelborg. In late November, the second platoon relieved the third platoon in The Hague; but a few weeks later, all three platoons were once again together near Legden in Burgsteinfurt.

On September 15, Group South began firing from positions in Germany near Euskirchen about 20 miles southwest of Cologne. Their targets included cities of varying importance: Arras, Amiens, Tourcoing, Brussels, Mons, Charleroi, Lille, Liège, Tournai, Diest, Hasselt, Maastricht, Cambrai, and Roubaix, all of which were soon to be in Allied hands. Battalion 836, under the command of Major Weber, continued in the Euskirchen area at sites Rheinbach and Kottenforst until the last week in September, when it moved across the Rhine River to the Westerwald area north of Montabaur.

From September 21 until October 3, there were four launching positions in the area of Westerwald (east of the Rhine River near Koblenz)—two near the town of Roßbach and two near the town of Helferskirchen. The command post of the third battery of Battalion 836 was situated in the Roßbacher Forest (District of Herrlichkeit), while the soldiers were billeted at Roßbach and Mündersbach. At Roßbach the launch sites were just off the main road with new paths created in half-circle tracks of 50 yards into the beech trees and then back onto the main road, which made it very easy for the long Meillerwagens delivering the rockets to maneuver in the wooded area. There were two firing pads there consisting of leveled ground covered in gravel. The second battery of Battalion 836, along with the headquarters battery, the technical battery, the flak train “Wojahn” (armed with antiaircraft guns), and the security platoon Sendezug/Funkhorchkompanie 725 (a unit for observation of trajectories and jamming signal) were established at Helferskirchen where the firing location was positioned about three-quarters of a mile south of the town. Under the standard of the battalion’s symbolic unit crest, which featured the figure of a witch riding naked on a broomstick, the third battery of 836 launched two rockets the next day toward Liège. These were the first V-2 rockets fired from the Westerwald. Only one was successful. The second rocket launched from Roßbach was a failure. The troops heard a huge thud at ignition; nonetheless, the rocket lifted normally into the sky only to explode after 40 seconds of thrust.

On September 27, 1944, enemy aircraft flew over the V-2 positions in the Westerwald area. Twelve Allied fighters bombed and strafed the railway stations at Hattert and Hachenburg and also the flak emplacements of the third firing battery, but no significant losses were reported. The battalion headquarters was soon established in Hachenburg, while the technical troops were stationed in the forest north of the road from Steinen to Dreifelden. From the railway station at Selters, the rockets were moved through Herschbach into the forest near Marienberg, where the Technical Troop checked and serviced them. After the warhead was mounted, each rocket was towed by the Meillerwagens over forested roads through the town of Roßbach and the Hachenburger Way to the firing sites.

The second battery of 836 fired seven V-2s in a 27-hour period, on September 27–28, but the site was abandoned the next day, and they were ordered to new emplacements across the Rhine to Saarland near Merzig (not far from the old training ground ground at Baumholder) to begin firing on Paris. General Kammler had ordered that all elements of Group South should concentrate their fire on the French capital. On October 3, the third battery, stationed at Roßbach, was ordered to join them; and by October 6, both batteries were in the Merzig area.

In the summer of 1944, as the Red Army was closing in on the Heidelager test range, R. V. Jones suggested to Winston Churchill that a technical team be sent to Poland to investigate the facility. Churchill agreed and immediately contacted Marshall Stalin to request access to the area at Blizna. Jones had assumed that the Air Ministry would be responsible for the mission; however, ultimately it was the Crossbow Committee that was charged with the Big Ben mission to the Soviet Union. A team of technical advisors led by Colonel T. R. B. Sanders, an engineer with a practical knowledge of ballistics known for his discretion and likeability, was to lead the Allied team. The relationship between Britain and Russia during the course of the war was marked by significant reservations. The appointment of a team leader having both substantial tact and diplomacy was important. Considerable negotiating skills, along with the ability to foster favorable relations, would be needed to secure the assistance of the Russians.

After permission was finally granted by the Russians, the party spent approximately two weeks in Teheran while waiting to get authorization from the Russians to fly to Moscow. Once in Moscow, another two weeks elapsed before the team actually reached Blizna on September 3. The party consisted of a mix of British and American personnel, who got on well together as well as with the Russians. Upon their arrival at the Heidelager camp, heavy fighting could be heard in the distance, as the front lines were only five miles away. The team quickly set about taking measurements, inspecting craters, collecting useful bits of rocket scraps, and interrogating Polish citizens. The firing platforms were the most remarkable discovery at Heidelager. Colonel Sanders was surprised to find out an area of only 20 square feet could be used to launch the V-2. The team managed to find a combustion chamber, a segment of the turbine casing, one of the fins, the framework of a radio compartment, and some smaller items, in all more than a ton of parts. Conversely, no evidence of railway wagons of any sort or storage tanks could be found. Looking for bits of rockets, some of the men also traveled to the target area to examine the impact sites. It was found that the Germans had been very thorough in collecting fragments, however. Of the many impact craters inspected, not a single large piece of scrap was found in the target areas. All of the collected material was crated up in Blizna and trucked to Moscow, where it would be shipped to Britain.

Colonel Sanders and his colleagues left Blizna on September 20, 1944, arrived in Moscow two days later, and flew back to London. As a result of the mission, it was found that there could be no countermeasures for the V-2. On the other hand, the rocket was found to be much smaller than anticipated, with a one-ton warhead, rather than the ten tons that some had predicted. Weeks later, a message from Moscow arrived in London with information that the rocket parts from Blizna had been “temporarily lost.” The crates were eventually sent on; however, when they were opened, authorities found not rocket parts but rusting scraps of motor cars. The Russians, after learning of the German long-range rocket program, had developed their own agenda.

After spending only two days at Walcheren, Battery 444 was ordered to travel north to Gaasterland in southwest Friesland, where it could continue operations against England. The battery traveled under the cover of darkness, as it was very risky to be on the roads during daylight hours because of Allied air superiority. After arriving in Friesland, Battery 444 set up operations in a small forested area called Rijs, south of the city of Balk. About 30 to 35 German officers of the battery were billeted in the nearby Hotel Jans. The Rijsterbos (Rijster Forest) was just off the waters of the IJsselmeer (Zuider Zee), a huge shallow lake in the center of Holland. Moving by train, the rockets left the Assen railway station bound for the station near Heerenveen at Sneek. At Heereveen they were placed on Vidalwagen road transport trailers of the supply troops and then towed by truck via the towns of Hommerts, Woudsend, and Harich, then into Balk. Dutch residents witnessed many vehicles and rockets parked beside City Hall in Balk. The rockets had to pass over a small bridge and make a difficult turn via the roads Van Swinderenstraat and Houtdijk. The Germans cleared trees away for maneuvering the trailers over the bridge that lead to Kippenburg. Even today, one can still see the scratches on the bridge where the V-2 trailers clipped the railing upon making the turn. At Kippenburg the rockets were prepared with their warheads and transferred to the Meillerwagen erector trailer. Behind the large estate house at Kippenburg, the propellant and warheads were stockpiled. The rockets were then moved via Rijsterdyk and Murnserleane a few kilometers southwest to the launching sites. Strung over the dark, unpaved, forested lanes of Murnserleane and Middenleane were large camouflage nets suspended high in the trees for further concealment from Allied aircraft.

With the V-2 having a maximum range of approximately 200 to 230 miles, it was not possible to target London from the location at Rijs. Instead, Battery 444 turned its attention to East Anglia and the territory surrounding Norwich in eastern England. Kammler was determined to continue the strikes on the British public from wherever possible, even it if meant targeting lesser cities.

On September 25, at 18:05 hours, after the trees and shrubs were sprayed with water to lower the fire danger, Battery 444 launched its first rocket toward northern England. Approximately five minutes later, the rocket hit a farm field at Hoxne in Suffolk, inflicting only minor damage to a few buildings nearby.

That same day, the rocket troops encountered their first misfire. A rocket had to be drained of its remaining fuel after the engine failed to generate full thrust. The ignition cable was burnt as the engine continued to fire while not leaving the launch table. Upon inspection, it was discovered that the rudders and tail section had been severely scorched, so the rocket was sent back for refurbishing. Closer investigation of other rockets from the Mittelwerk had revealed many additional problems. Bad welds, missing parts, short-circuited electrical connections from inferior soldering—these were just some of the mechanical errors discovered. Not only did the crews face difficulties from the quality of the rockets, there also existed an acute shortage of liquid oxygen. German production had only reached a level of about 200 cubic meters per day, which is only enough to launch 24 rockets. The logistical problems of firing batteries on the move and V-2 units spread out from northern Holland to western Germany did not help matters.

Late in the afternoon on September 26, a loud double boom was heard near the English village of Ranworth. The rocket plowed into a field about eight miles outside of town. The sound of the explosion was followed by another loud sonic boom and then the whine of rushing air. Windows of cottages were shattered within a half-mile radius of the blast. Officials in Britain quickly knew that the V-2 campaign had come to East Anglia. There had been a reduction in the frequency of V-2 attacks since the beginning of the Market Garden offensive, but still no word concerning the nature of this new German weapon had passed from British authorities to the populace. These mysterious bangs were new to the citizens of Norwich. Even some of the nearby military establishments were unfamiliar with the new threat and recorded these first impacts as aircraft crash sites.

At Rijs, the Dutch citizens were unsure of just what was going on near their homes. They only knew that it was a dangerous operation. The entry lanes to the forest were strangely blinded with canvas. They could hear on German radio the propagandists heralding the new Wunderwaffen (wonder weapons) but were unsure what this meant. Weeks later the BBC reported that it was the V-2 rocket falling on England. It was forbidden to come close to the launching sites, and very few people risked being caught near the area. Not only was there the danger of the German guards, there also was the peril of failed rockets crashing in the immediate area.

On the afternoon of September 30, a V-2 was launched from Rijs. It rose to a height of 600 feet before an explosion in the rocket’s tail brought it crashing to earth about 20 yards from the firing table. The alcohol and liquid oxygen tanks exploded upon impact, injuring some of the firing crew. The warhead sizzled in the burning fuel and exploded approximately 45 minutes later, digging a huge crater. This failed rocket had ironically destroyed a small shrine in the forest called Vredestempeltje (the little peace temple). Despite the mishap, a new launch site was quickly established a few hundred yards away.

Several weeks later, Wieger Jurjen Draayer, a local farmer, was riding his bicycle along the lanes just beyond the Rijs Forest near Bakhuizen. As there had been strange noises and unknown things seen in the sky for the past several weeks, Wieger was anxious to get home. In the distance he suddenly heard a thump followed by a tremendous roar. The bicycle he was riding came to a stop, and he let it fall to the ground. Racing to a nearby ditch, he peered out to witness a huge steeple-shaped object trailing a tail of fire rising from the forest ahead of him. The object was arcing above him when something went wrong. The noise from the projectile ceased, followed by a whistling as it fell from the sky. There was a tremendous explosion some 70 yards from where Wieger hugged the side of the ditch. Quickly, Wieger got on his bicycle again and started peddling as fast as he could. Tiny bits of material were floating down all around him, almost like snow. He noticed three dead cows in the field near the forest. The explosion left a crater some 20 feet deep and 30 feet wide. As he approached an intersection, a group of German soldiers called for him to stop. The soldiers were surprised to see the farmer riding so close to the V-2 launching area. They asked if he was injured and told him this was a restricted area and to stay away in the future. The dazed and confused Wieger hurried to his home.

For the Dutch residents of the surrounding countryside, it was a very nervous time. Every day they could hear the thunderous noise of the V-2 launches and lived in fear that something might go wrong. The farmers soon knew if the rocket did not rise vertically, anything could happen. Failed rockets would fall in the immediate area, sometimes near the residents’ homes. Other V-2s encountered problems at higher altitudes, and the farmers watched them plunge into the waters of the IJsselmeer just off shore.

For the soldiers of Battery 444, the stress of the launches was just as great. Many of them would rather have been occupied with some less hazardous job. However, there was plenty of Dutch gin to help them ease their tensions. British fighter planes searched the area several times; however, the ability of Battery 444 crews to launch and retreat quickly made it difficult to spot anything from the air. The Rijs Forest V-2 sites, with very tall trees, provided excellent camouflage; but there was always the possibility of an air attack, and the rocket troops were very wary of this.

On October 3, marking the second anniversary of the first successful A-4 launched from Peenemünde, the rocket troops at Rijs fired six missiles toward the Norfolk countryside. Throughout the day, thunderous detonations reverberated at regular intervals. From their homes, the people of Norwich could see huge columns of black smoke in the distance rising high into the air. The strikes were gradually coming closer to the populated sections of the county. Late that evening, an explosion rocked the Hellesdon area. An estimated 400 houses within a two-mile radius were damaged in some manner. The following day British authorities recovered the remains of a V-2, which broke up in the air before impact near Spixworth. The engine and various important parts were sent to Air Institute at Farnborough for analysis.

The last rocket to fly toward England from Rijs was launched on the morning of Thursday, October 12. It fell innocuously in the open near Ingworth without much commotion, demonstrating the folly of targeting anything less than a large urban city with the V-2. From September 25 to October 12, Battery 444 launched approximately 43 rockets toward East Anglia. Without heavily populated English targets within range, the results were not satisfactory. British casualties from V-2 attacks in East Anglia ended up relatively light. Only one person had been killed as a result of the attacks, and less than 50 people were wounded. The damage in Suffolk and Norfolk counties was limited to only a modest amount of houses, barns, farms, and schools. Many V-2s struck empty fields and even the North Sea.

The campaign against East Anglia ended on October 13 after new orders were received to begin targeting the port of Antwerp. Most Battery 444’s initial shots toward Antwerp missed their mark, falling short in and around the suburbs of the port city. However, on October 16, 1944, they scored a direct hit, when a V-2 slammed into dock number 201 in the harbork, completely demolishing it.

In October, RAF Fighter Command began a new operation designed to impede the German rocket crews in Holland. Big Ben patrols, or anti-V-2 missions, were mounted by several RAF squadrons, which used armed reconnaissance and dive-bombing sorties to attack the rocket areas on the Dutch coast. Flying out of Coltishall, No. 602 Squadron RAF was brought in to patrol for V-2s on October 10. They joined in with No. 229 Squadron RAF, which had already been in operation against the rocket sites since September. Both the RAF and the U.S. Army Air Force did their best to locate the missiles, and on many occasions sent hundreds of fighters over Holland to strafe anything that looked like a target. However, because of the rocket’s surreptitiousness and the heavily camouflaged firing positions, it proved almost impossible for pilots to locate the rocket batteries on the ground. Even so, the fighter-bomber sweeps shot up a lot of vehicles and railway cars and were partially responsible for shortages of liquid oxygen and other supplies at the V-2 launch sites.

After three weeks, Battery 444 disappeared from Gaasterland just as quickly as it had arrived. The last rocket fired from Rijs headed for the port of Antwerp on the morning of October 20. Suddenly the Germans packed and moved south that same day. SS General Kammler had ordered the unit back to The Hague following the failure of Market Garden.

Ever since the first rocket was fired from Rijs, British radar momentarily tracked the incoming missiles. In addition, Allied pilots reported sightings of contrails from ascending rockets near Gaasterland. However, these only gave an approximate location of the firing positions. After several weeks, an RAF reconnaissance aircraft brought back a photograph showing clear evidence of activity in the forest. On October 21, a flight of seven Tempest fighter bombers of the No. 274 Squadron RAF flew near the Rijs Forest and finally located the launching sites. They flew by heading east, just north of the forest, and after forming up in a line, the seven aircraft turned back to attack the area. Not only did the aircraft drop bombs in the forest, they also shot up the surrounding houses and buildings. Luckily, farm animals were the only victims of this attack, although some civilians narrowly escaped being hit. But the RAF found the launching sites only a few hours after the last Battery 444 vehicles exited the area. The British were unaware that the rocket units were gone, and the bombers returned each of the next few days to attack the forest. By this time, the firing platoons of Battery 444 were arriving in The Hague to join Battalion 485 for operations against London.

The people around Rijs were relieved to see the German V-2 menace departed. They returned to their everyday life, as it was in wartime, without the threat of exploding missiles on their homes. Actually, they were very lucky. There had been no Dutch civilian casualties. If not for the light population of the area and the fact that the missiles were traveling over the IJsselmeer after launching, the casualties may have been severe. Moreover, the relatively short three weeks of operations meant there was very limited damage. Later, on clear winter days, they could see the V-2s rising from the Eelerberg over 100 kilometers away to the south. They could easily imagine the terror felt by their neighbors there, who must be enduring the same nightmare they experienced only a few months before.

Now that Montgomery’s offensive had been defeated, the V-2 batteries which had retreated to Germany began returning to The Hague. They selected the large, adjoining, open areas of Bloemendaal and Ockenburgh, far removed from the built-up city center, for their firing sites. On October 3, the first Meillerwagen of the second battery of Battalion 485 drove into Ockenburgh at 9:00 in the morning. Later that evening, they launched a V-2 at 11:00 PM, followed by another 45 minutes later, which exploded shortly after liftoff, lighting up the whole city. The V-2 had returned. On October 7, V-2s began being launched from the Bloemendaal site. Because of the launch site locations, the RAF decided they could bomb them without risking too many civilian casualties. After several days of bad weather, six aircraft dropped their bombs on Ockenburgh and Bloemendaal in the early morning of October 18. At Bloemendaal the bombs damaged a rocket resting on a Meillerwagen that was unconcealed, out in the open.

In early October, German commanders first considered the possibility of firing V-weapons against Antwerp. The objective would be to smash the harbor installations so effectively that they would be useless to the Allies even after the approaches to the harbor had been cleared of German resistance. On October 12, 1944, the Führer ordered all V-2 fire be directed at London and Antwerp exclusively. Attacks on all other targets would stop.