USS Olympia (C-6/CA-15/CL-15/IX-40) is a protected cruiser that saw service in the United States Navy from her commissioning in 1895 until 1922. This vessel became famous as the flagship of Commodore George Dewey at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War in 1898. The ship was decommissioned after returning to the U.S. in 1899, but was returned to active service in 1902.

She served until World War I as a training ship for naval cadets and as a floating barracks in Charleston, South Carolina. In 1917, she was mobilized again for war service, patrolling the American coast and escorting transport ships.

After World War I, Olympia participated in the 1919 Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War and conducted cruises in the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas to promote peace in the unstable Balkan countries. In 1921, the ship carried the remains of World War I’s Unknown Soldier from France to Washington, D.C., where his body was interred in Arlington National Cemetery. Olympia was decommissioned for the last time in December 1922 and placed in reserve.

The newly formed Board on the Design of Ships began the design process for Cruiser Number 6 in 1889. For main armament, the board chose 8 inches (200 mm) guns, though the number and arrangement of these weapons, as well as the armor scheme, was heavily debated. On 8 April 1890, the navy solicited bids but found only one bidder, the Union Iron Works in San Francisco, California. The contract specified a cost of $1,796,000, completion by 1 April 1893, and offered a bonus for early completion.

During the contract negotiations, Union Iron Works was granted permission to lengthen the vessel by 10 ft (3.0 m), at no extra cost, to accommodate the propulsion system. The contract was signed on 10 July 1890, the keel laid on 17 June 1891, and the ship was launched on 5 November 1892. However, delays in the delivery of components including the new Harvey steel armor, slowed completion. The last 1-pounder gun wasn’t delivered until December 1894.

Union Iron Works conducted the first round of trials on 3 November 1893; on a 68 nmi (126 km; 78 mi) run, the ship achieved a speed of 21.26 kn (39.37 km/h; 24.47 mph). Upon return to harbor, however, it was discovered that the keel had been fouled by sea grass, which required dry-docking to fix.

By 11 December, the work had been completed and she was dispatched from San Francisco to Santa Barbara for an official speed trial. Once in the harbor, heavy fog delayed the ship for four days. On the 15th, Olympia sailed into the Santa Barbara Channel, the “chosen race-track for California-built cruisers,” and began a four-hour time trial. According to the navy, she had sustained an average speed of 21.67 kn (40.13 km/h; 24.94 mph), though she reached up to 22.2 kn (41.1 km/h; 25.5 mph)—both well above the contract requirement of 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph). While returning to San Francisco, Olympia participated in eight experiments that tested various combinations of steering a ship by rudder and propellers. The new cruiser was ultimately commissioned on 5 February 1895. For several months afterwards, she was the largest ship ever built on the western coast of the US, until surpassed by the battleship Oregon.

Scientific American compared Olympia to the similar British Eclipse-class cruisers and the Chilean Blanco Encalada and found that the American ship held a “great superiority” over the British ships. While the Eclipse’s had 550 short tons (500 t) of coal, compared to Olympia’s 400 short tons (360 t), the latter had nearly double the horsepower (making the ship faster), more armor, and a heavier armament on a displacement that was only 200 short tons (180 t) greater than the other.

Upon commissioning in February 1895 Olympia departed the Union Iron Works yard in San Francisco and steamed inland to the U.S. Navy’s Mare Island Naval Shipyard at Vallejo, where outfitting was completed and Captain John J. Read was placed in command. In April, the ship steamed south to Santa Barbara to participate in a festival. The ship’s crew also conducted landing drills in Sausalito and Santa Cruz that month. On 20 April, the ship conducted its first gunnery practice, during which one of the ship’s gunners, Coxswain John Johnson, was killed in an accident with one of the 5-inch guns. The ship’s last shakedown cruise took place on 27 July. After returning to Mare Island, the ship was assigned to replace Baltimore as the flagship of the Asiatic Squadron.

On 25 August, the ship departed the United States for Chinese waters. A week later, the ship arrived in Hawaii, where she remained until 23 October due to an outbreak of cholera. The ship then sailed for Yokohama, Japan, where she arrived on 9 November. On 15 November, Baltimore arrived in Yokohama from Shanghai, China, to transfer command of the Asiatic Squadron to Olympia. Baltimore departed on 3 December; Rear Admiral F.V. McNair arrived fifteen days later to take command of the squadron. The following two years were filled with training exercises with the other members of the Asiatic Squadron, and goodwill visits to various ports in Asia. On 3 January 1898, Commodore George Dewey raised his flag on Olympia and assumed command of the squadron.

As tensions increased and war with Spain became more probable, Olympia remained at Hong Kong and was prepared for action. When war was declared on 25 April 1898, Dewey moved his ships to Mirs Bay, China. Two days later, the Navy Department ordered the Squadron to Manila in the Philippines, where a significant Spanish naval force protected the harbor. Dewey was ordered to sink or capture the Spanish warships, opening the way for a subsequent conquest by US forces.

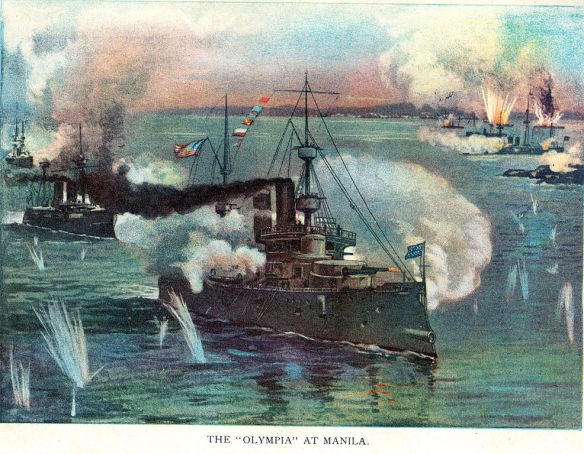

On the morning of 1 May 1898, Commodore Dewey—with his flag aboard Olympia—steamed his ships into Manila Bay to confront the Spanish flotilla commanded by Rear Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón. The Spanish ships were anchored close to shore, under the protection of coastal artillery, but both the ships and shore batteries were outdated. At approximately 05:40, Dewey instructed Olympia’s captain, “You may fire when you are ready, Gridley”. Gridley ordered the forward 8-inch gun turret, commanded by Gunners Mate Adolph Nilsson, to open fire, which opened the battle and prompted the other American warships to begin firing.

Though shooting was poor from both sides, the Spanish gunners were even less prepared than the Americans. As a result, the battle quickly became one-sided. After initial success, Dewey briefly broke off the engagement at around 07:30 when his flagship was reported to be low on 5-inch ammunition. This turned out to be an erroneous report—the 5-inch magazines were still mostly full. He ordered the battle resumed shortly after 11:15. By early afternoon, Dewey had completed the destruction of Montojo’s squadron and the shore batteries, while his own ships were largely undamaged. Dewey anchored his ships off Manila and accepted the surrender of the city.

Word of Dewey’s victory quickly reached the US; both he and Olympia became famous as the first victors of the war. An expeditionary force was assembled and sent to complete the conquest of the Philippines. Olympia remained in the area and supported the Army by shelling Spanish forces on land. She returned to the Chinese coast on 20 May 1899. She remained there until the following month, when she departed for the US, via the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean Sea. The ship arrived in Boston on 10 October. Following Olympia’s return to the US, her officers and crew were feted and she was herself repainted and adorned with a gilded bow ornament. On 9 November, Olympia was decommissioned and placed in reserve.