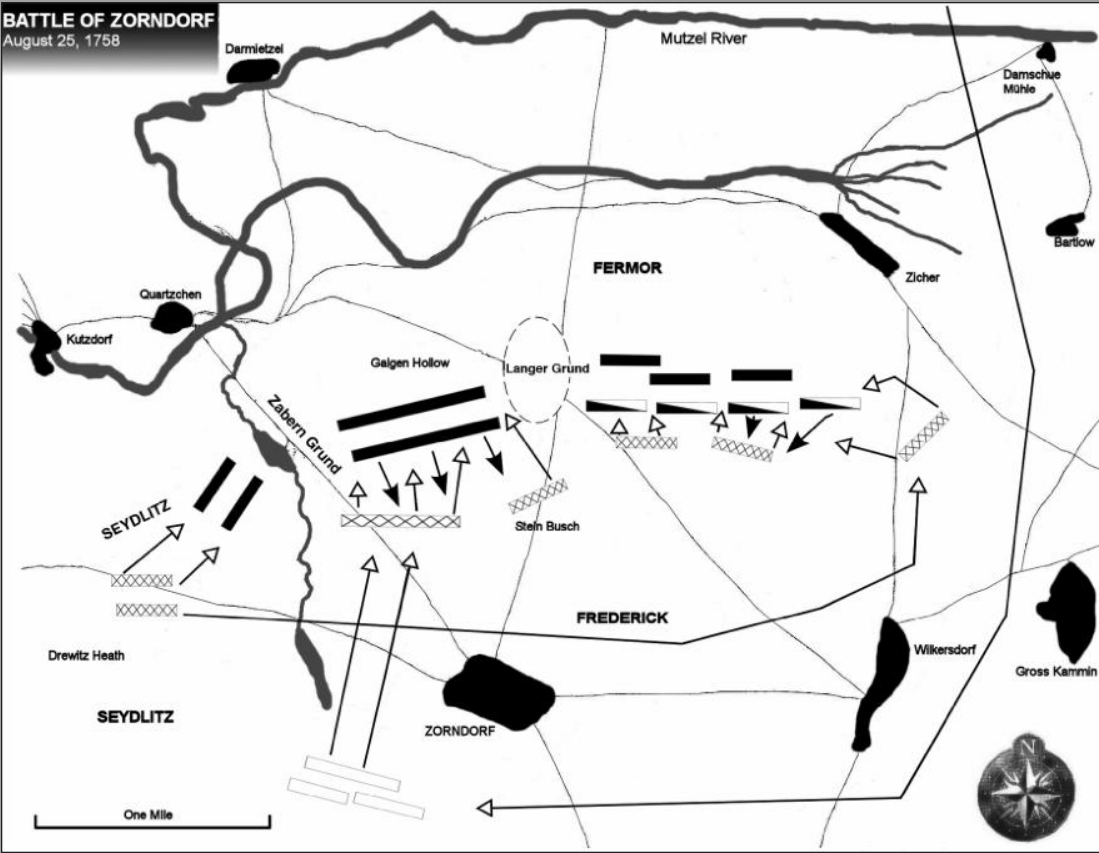

The Russian right was no longer capable of organized resistance, but an incredibly bloody and desperate struggle was kept up there until about 1300 hours when the Prussians finally became exhausted. Kanitz’ attack had smashed through three solid lines of Fermor’s deep front and the momentum there was definitely in Prussian hands. Seydlitz drew back his cavalry to reform them in case of additional need. The Russian line there having been driven in, the center and left were reformed, taking up a second line in front and to side of the Galgen Grund. Browne’s observation corps, the largest remaining intact Russian formation, swung itself in to become the new Russian left, while the rest of the survivors of the morning debâcle became the new Russian right wing. What part Fermor had to play in any of these proceedings is unclear, before his wound. Russian generals would later complain of the lack of orders they received during the battle from their “commander.” They could not move well or dexterously in their thickly crowded formations. But neither could their foes of the Prussian left, who had been heavily involved in the battle and were tiring by then. Frederick, seeing Kanitz’s men faltering, ordered the right wing, which was still relatively fresh, into action.

Earlier the king had ridden across to the latter command to see why Dohna was making no attempt to aid Kanitz, even when it became apparent he was in dire need of reinforcements. In point of fact, the right had been withdrawing slowly further and further from the scene of action, just when its support was most needed. Responding to orders, Dohna shoved his men into an assault on the southern side of the great enemy center square. The latter was to use his anchor on the Langen-Grund to prop up his men, while units of Schorlemer’s and Marschall’s cavalry would keep the enemy horse at bay. In the meanwhile, the remaining units of the Prussian center and right, those formations still capable of fighting, were shifted eastwards to the ground in front of the Russian center. By mid-afternoon, Frederick’s main attack pressure was facing north. The bluecoats deployed into battle lines again, while the big 40-gun battery was moved—about 1300 hours—from the Zaberngrund to the Galgen Grund, under the escort of the 40th Infantry. It then opened a steady and deliberate fire against the massed Russian army. About 1330 hours, the firing again became general, as the reformed Prussian infantry, this time from the left, prepared to advance against the new enemy position.

General Browne’s men were taking a horrific punishment from the Prussian battery. For two full hours, the shelling and sparring continued. Then, about 1500 hours, the Russians struck. Browne’s sole aim was to silence that infernal battery. His Horvat Hussars galloped over the intervening country and quickly took the Prussian guns, and simultaneously nabbed Kreutz’s infantry battalion. This was the signal for a general attack by the whole of Demikow’s cavalry. Their stroke was initially successful, but the iron discipline of the bluecoats as their infantry formed to repulse the intruders was in the end decisive—1515 hours. Then Schorlemer’s surging horsemen rode them down and drove the Russian riders into the near-by Zicher Woods for shelter.

This effort raised manifold clouds of smoke. The Prussians of Manteuffel’s still unsteady command momentarily panicked in the mistaken belief the intruders were enemy cavalry. They insensibly tended towards Wilkersdorf before the error could be discovered. Demikow’s effort had one other result. Dohna’s men were still cognizant of the Russian horse, but the retreat of the Horvat Hussars allowed the freed battery to resume pounding Browne’s men. Browne had been reinforced by four battalions from the Russian Major-General Manteuffel. Browne launched a renewed counterattack, at about the same time as Demikow’s effort. This was one determined stroke.

Just past the batteries (which were by then blasting away far out in front of the main army) the Russian cavalry surged forward to come to grips with Frederick’s foot soldiers out beyond the confines of their lines. Simultaneously or nearly so, the long lines of Russian infantry ran out to support their comrades on horseback. The main rush of Fermor’s troops was straight into the battalions in position at the Prussian center, rather than against the flank forces, which were nevertheless driven in against the center. The Russians came on like men possessed, capturing another battery and an entire Prussian battalion. So from about 1430 hours, the battle here largely degenerated into a confused slaughter.

The Prussian center, hit by the enemy in this fierce assault, rolled back, the units showing an unsteadiness unusual for Prussian troops. They fell back forthwith and not until they reached Wilkersdorf, more than a mile from the scene, were they finally rallied by their officers. Their brethren on the flanks, fortunately for the Prussian cause, were better able to withstand the enemy’s stroke. For the most part, the latter managed to hold their ground against Fermor’s strong counterattack. Seydlitz, in the midst of this mess, came on once more (about 1530 hours): he had rested and reassembled his troopers, bringing up the reserves (giving him a grand total of 61 squadrons ready for orders), now once again the indomitable cavalry leader prepared again to take matters to his own. Seydlitz swept forward into the milling Russian mass from front and rear, rode down the enemy and drove them back upon the Mutzel and Quartzchen beyond.

Now, once again, Dohna was making his presence felt. His troops, plus the survivors of Kanitz, some 900 strong, reinvigorated by the sight of Seydlitz’s magnificent cavalry assault, surged forward (about 1530 hours) with bayonets at the ready into the tumbling, utterly decimated enemy lines. But Dohna’s first stroke hit the packed Russian line a glancing blow, and his men momentarily wavered. This was a period of vulnerability. Fortunately, Schorlemer’s horsemen were able to keep rank for the more than 3/4 of an hour necessary to recover. Precious time to get matters straight. Prussian guns, brought forward on the run, opened a savage fire and, at approximately 1635 hours, the bluecoats went back to the attack. This stroke, better supported and prepared, proved the finish. Browne’s men held rank for a time, and then lost all cohesion. By 1715 hours, the Russian guns were silenced as they were overrun, their operators killed or captured in the process. Now was the time Dohna looked for, the Prussian cavalry “should” have launched a decisive attack. But Seydlitz’s men were done in, and Schorlemer’s horse was shaken by its previous efforts. No cavalry stroke came. The situation was still bad enough for the Russians. Georg Browne fell severely wounded in this final showdown; he and “Colonel Soltikow [Soltikov] were taken prisoners by some hussars.”

The Russians were slaughtered like pigs in a pen, but they did not run. They stood to their duty, and were often cut down where they were. By a little past 1600 hours, organized resistance virtually ceased, as the slow destruction of the Russian army started. I will spare the reader the details; suffice it to say that more blood was spilled that day than on any European battlefield in half a century. At Zorndorf, the Prussians discovered the Russian pay chest, valued by Lloyd at £160,000 in 1780 money.

After the battle, and with a misguided sense of justice, St. Petersburg blamed their own army for the sacking of the pay chest, when this nefarious deed was committed by Prussian cavalry alone. The details of this whole business are very disturbing. Russian soldiers were even individually frisked for the missing coins, and a communiqué from home accused the whole army of drinking on the job, even of “wanton cowardice” in the face of the dreaded Prussian king and his legions.

At the event, the Russians could not flee. Indeed, how could they have gotten away? Many of them “attempted” to cross the flowing waters of the Mutzel, by now running red with blood, but could not make it and were swallowed, man and beast alike, in the oozy marshes near the river. Meanwhile, the Prussians were drawing back again and again to rest, while their foes, packed often like sardines in a can, had not even the luxury of freeness of movement. A lone body of Fermor’s men, gathered up from among the remnants of the units, were put under Demikow. This force managed to move back into the hollows where their army had stood. Fermor, apparently patched up, was back by then. He assembled what formations could still offer an organized front—on the Galgen Grund. These hardy units included the famous Smolensk and Kazan Musketeers. There, surrounded by a dreadful number of dead and wounded countrymen and Prussians, Demikow made preparations to defend the withdrawal of the army, as soon as it was possible. He reached his destination just as dusk was falling, the main knoll now the key to the battlefield. Nearby, the broken remains of the badly used Russian formations could offer little tangible support to Demikow.

As for the Cossacks, organized they could have proven invaluable at this stage of the battle. Instead, they were busy rummaging through the paraphernalia they found on the battlefield, from both friend and foe. Lost in the joy of plunder, the Cossacks were useless for salvaging the lost battle.

Frederick, noticing the small organized enemy force forming up in its hollow just when Russian resistance was supposed to be largely at an end, instantly—about 1900 hours—ordered Forcade with the 23rd Infantry, which had performed commendably during the battle, to march to attack Demikow’s force from the front. General Samuel Carl von Rautter’s 4th Infantry and the rest of the Prussian center (shaken though it was), was to move round and encircle the flanks. The Russians with Demikow responded to the Prussian advance with some artillery shelling, which threw panic into Rautter’s men, who flew wildly to the rear and were not rallied again that day. In fairness, it must be admitted the 4th Infantry suffered heavily at Zorndorf. The tally was 28 killed, 206 wounded, and 176 “missing or captured.” The 11th Infantry of Lt.-Gen. Below was another of those battered units. Its tally at Zorndorf was 707 men and 19 officers. Forcade, from the distance, opened up with his guns in reply (perhaps it had been one of his salvoes that had panicked Rautter’s troops in the first place), but did not attack, as he now had no support. The enemy replied with their guns, but Demikow did not withdraw.

Forcade kept his cool; he ordered his troops to deploy while the gunners kept up the involved work of hammering the Russian lines. However, there was to be no further developing of the attack, as the king soon sent a courier to Forcade to leave Demikow alone. The Prussians withdrew towards the main army. For the shameful conduct of his men, Rautter was relieved of his command after the battle and replaced by General Georg Friedrich von Kleist. The main mass of the Russians fell back but slowly, Fermor finally regained control of his army, but far too late. He could now do nothing to reform it and even some of the battlefield was fully in the hands of the Prussians. Frederick’s men dealt with the roving bands of the Cossacks in a heartless—but effective—way, getting in a bit of revenge for the atrocities of the Russians. In one incident, the hussars surrounded one barn near Zichar and burned it down, killing 420 Cossacks that were trapped inside. Archenholtz mentions the deed, and even says the number “was near a thousand.”

In the meantime, the coming of night and the end of the battle (which was effectively over by about 1700 hours) brought about preparations for encampment. Frederick ordered his men to pitch their tents and put into bivouac for the night in two lines of rank. This was north to south, with his tent placed in the first row, while guards were posted and parties pushed out to probe the woods and scout out Fermor’s new position, now beyond the roads off in the distance. The sheer exhaustion of the Prussians had allowed Fermor to disengage his army from the battle. The latter, during the course of the night of August 25–26, gradually reassembled his army in some order. The men, now ranked in a loose marching order, then moved towards the southwest far to the west of the Zaberngrund into the Drewitz Heath (still on that side of the Oder); there, hidden among the dense patches of forests, which offered cover from the preying eyes of the enemy’s hussars and providing protection from a surprise Prussian attack, Fermor’s thoroughly worn out troops finally found time for sleep.

Within the gloomy, dejected atmosphere of defeat prevailing in the Russian camp that night, there were fewer than 29,000 fit men after the bloody battle. These men were scattered around the countryside in the thick woods of the region. This was not exactly the way Fermor anticipated his invasion of Brandenburg would turn out. His men had been weakened by the many hours of heavy fighting, some units had been almost totally wiped out, others were scattered and often their very own officers, if they were still in a position to care, did not know where they were. Frederick, who had brought a somewhat smaller force to the battle, had about 18,000 fit men in the ranks that night.

He had attacked, and with great effort, overcome the very formidable Russian army, but he had had to pay a big price for that “privilege.” Reports that the enemy had marched off were received throughout the night by the Prussians. They, too, however, were waiting for the dawn. General Peter Ivanovitch Panin was bold enough to say, although the Russian array had indeed retained largely the field of battle, “it was either dead, wounded or drunk.”

Early the following morning, August 26, Fermor rose from his encampment and marched back beyond the Zaberngrund, where he halted and formed his men into line-of-battle. The Russian commander sent a request to the Prussian commander opposite to him (Dohna) for a three-day truce. He wanted to utilize the time to bury the dead and help the wounded. Among the latter was General Browne, who was in desperate need of medical attention. But Dohna rejected the request on the premise that it was customary in military history for the victor of a battle to ask for a truce and he certainly did not want to give Fermor the impression Zorndorf was a Russian victory.

Dohna was quick to mention the misdeeds committed against innocents. Nevertheless, he did acknowledge Browne’s need for assistance and offered an accommodation. It was all academic, though, for before a reply could be definitely received (raising the possibility this was a mere ruse), Fermor drew out his front with his army facing the battlefield to the east. Unlimbering his guns, the Russian commander commenced a cannonade across the field upon the Prussians. The range was too great to accomplish anything direct except to show the foe the Russian army still had fight left in it. As proof, the king rode out early that morning to scout Fermor’s latest movements. The trip was uneventful until he reached the village of Zorndorf. Then an enemy of unknown strength fired at him, nearly taking out Frederick. Both sides opened up with their guns, possibly leading to the renewal of the fighting.

The Prussian response was swift, the king’s men drew out in front of their bivouac and forming into battle order replied with their big guns, giving an appropriate answer. Men on both sides urged attack on their leaders, but exhaustion from the heavy fighting of the previous day as well as a critical shortage of ammunition stifled any chance of attack by either side. At about 1130 hours, the Prussians, seeing nothing coming from Fermor’s quarter, marched back to their tents, leaving the artillery to keep up the exchange with the enemy.

Late the previous night, Prussian hussars had ridden straight into Fermor’s heavy baggage train at Klein-Kammin. The hussars took their time and plundered the train. Now, in the daylight, with Frederick at Zorndorf and thus between Fermor and his train, it would have been advisable for the king to march and stomp this train before Fermor could lift a finger to rescue it. This would have been decisive, for with his baggage gone, the Russian commander would have been in a big hurry to return to Poland. Inexplicably, nothing of the kind was forthcoming. Perhaps Frederick did not consider it important enough. He may have felt that Fermor was already beaten, so the thing was not worth the effort. Whatever the cause, the Russian baggage was left without further disturbance.

Back at the field, the Russian bombardment gradually calmed down, and darkness fell upon the tortured field. About 2300 hours, the Russian army started to move through the woods leading to Tamsel and the road to Klein-Kammin. As he drew away, Fermor ordered a renewed shelling laid down to conceal his retreat. One of these latter rounds blew up a carriage parked outside the king’s tent. The smoke of the cannonading combined with a thick fog arising from the Oder served to conceal the Russian withdrawal.

The Prussians were unaware of what was happening until the enemy had already gotten clean away to Klein-Kammin and were preparing for breakfast. Finally Frederick’s reconnaissance parties detected the Russian maneuver, and he at once set off in pursuit. When the king’s men reached the vicinity of the enemy’s encampment, Fermor was already secure behind his redoubts and had his artillery train parked with unlit fuses set. Frederick chose not to attack the Russian position, which was probably a very wise move, and settled for a peaceful withdrawal back to his own camp. So confident was Fermor in the capabilities of his post that, beaten at Zorndorf though he may have been, it was not until August 31 that he abandoned Klein-Kammin and started back towards Landsberg.

Frederick, one among many on the Prussian side, was glad to see the Russians go, and did not consider a long-range pursuit using the main Prussian army. The Russians had proven themselves to be worthy opponents. Worthy opponents indeed. In fact, “[The Russians] sustained a slaughter that would have confounded and dispersed the compleatest [sic] veterans.” Three days after Fermor’s final retreat (September 2) the Prussian king gathered his troops and marched towards Saxony to see to the situation in that province. He did see good to detach Dohna with a large detachment—21 battalions and 35 squadrons, some 17,000 men—to go into Fermor’s rear and help see him go. Dohna at once took up his job.

Thus closed the story of the Battle of Zorndorf, the hardest fought battle of the Seven Years’ War, and one of the worst of the entire eighteenth century. The casualties reflected that singular fact: Fermor lost 7,990 killed/13,539 wounded and missing; a total of 21,529, nearly half of the army he had dragged to Zorndorf. The beaten side also lost 103 guns and 27 standards, meaningless compared to the human suffering. Frederick’s army suffered as well, although not as severely. Prussian losses were 3,680 killed, above a thousand men missing from the ranks (presumed dead /deserted/captured); along with the wounded, approximately 11,390 men from all causes. Thus nearly four in ten of the Prussians present at Zorndorf were casualties.