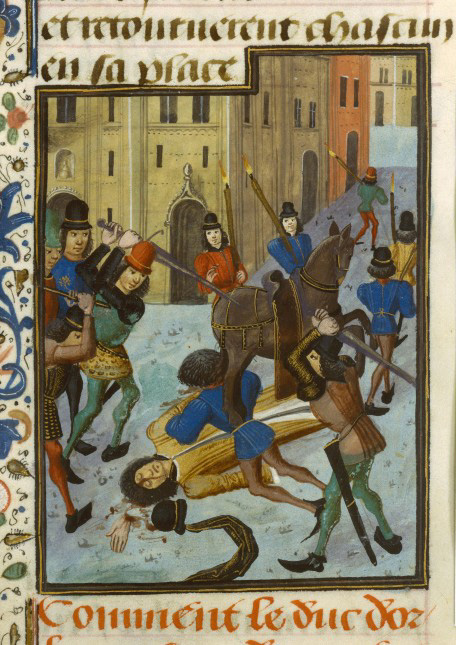

Assassination of Louis I, Duke of Orléans in Paris in 1407

These were terrible times for the Armagnac princes. They were among the greatest noblemen in France and traditionally the closest to the Crown. Yet they had been cut off from the King and expelled from their domains. Their networks of clients and protégés in the administration had been destroyed. Their access to government funds had been terminated. Across northern France their supporters were being attacked and murdered. Some towns like Dijon took their cue from Paris and banished known Orléanists, confiscating their property. In Champagne mobs attacked the castles of prominent Armagnacs. The Count of Roucy, one of the greatest lords of the region, was besieged in his castle at Pontarcy on the Aisne by more than 1,500 irate peasants with the overt encouragement of the royal bailli of Laon. In the lands that remained to them the princes found themselves attacked as traitors as their erstwhile friends began to slip away in search of better fortune elsewhere.

The burden of rallying his battered party and financing the continuance of the war fell on the eighteen-year-old Charles of Orléans, already struggling to pay the arrears of the previous year’s disastrous campaigns. He sold off or melted down most of what remained of his family’s silver plate. He taxed his domains in the Loire valley. He continued to hope for wider recognition of the justice of his cause next time. The mercers of Orléans were making banners bearing the motto ‘Justice!’, with which the young duke planned to confront the Duke of Burgundy in the spring. An order for 4,200 cavalry pennons suggests that an army of at least 10,000 men was planned, which was much the same as he and his allies had deployed in 1411. But when the leaders of the coalition came to assess their position at the beginning of 1412 it was apparent that it would not be enough to confront the great armies that the Duke of Burgundy was now able to recruit. In desperation the princes resolved upon another attempt to recruit an English army for their cause. To do this they would have to outbid the Burgundians, with their extensive resources and established connections in England.

It is unlikely that either of the warring parties in France understood the complex and volatile political situation in England. When the Earl of Arundel left England the Prince of Wales had been the dominant figure in government. He had consistently favoured an alliance with the Duke of Burgundy. But although Arundel’s expedition had contributed much to the triumph of Burgundian arms, it had achieved very little for England. The diplomats who had accompanied him to Arras had been unable to extract anything but money in return for his services. By the time that Arundel returned to England the ailing Henry IV had succeeded in wresting power back from the Prince and his friends. The circumstances are obscure, like all of the court intrigues of Henry IV’s declining years, for the chroniclers observed a prudent reticence on the subject. On 3 November 1411, while the Earl of Arundel was in Paris, Parliament opened at Westminster. As the day approached it became obvious that the King was too ill to preside in person at the opening. The Prince appears at this point to have confronted his father and suggested that it was time for him to abdicate. He told him, according to the only surviving account, that he was ‘no longer capable of acting for the honour and profit of the realm’. The King indignantly refused. During the sessions of the assembly the Prince and Henry Beaufort Bishop of Winchester called a meeting of the leading lay and ecclesiastical peers to consider the issue. One of them, they said, would have to summon up the courage to persuade the King to go. He was disfigured by ‘leprosy’ and therefore unfit to perform the public duties of his office.

In the course of November, however, Henry IV succeeded in reasserting his authority. He mustered enough strength to make occasional appearances in Parliament. In some of them he even showed his old assertive style. On 30 November he dismissed the Prince and the entire royal council. This was followed in the closing days of the Parliament by the replacement of all the principal officers of state. Sir Thomas Beaufort was replaced as Chancellor by Archbishop Arundel and the Treasurer by the household knight Sir John Pelham, both of them close to the old King and no friends of his eldest son. Henry of Monmouth could hardly be excluded from the public life of the realm. But much of his influence passed to his younger brother Thomas of Lancaster. These changes profoundly destabilised the English government. Thomas of Lancaster, then twenty-five years old, had for some years been the King’s favourite son. He was a soldier of reckless courage and furious energy, but a man of poor judgment and little appetite for business who was on bad terms with both the Prince and his Beaufort friends. Henry of Monmouth did not take well to being supplanted by him. As the heir to an ailing King and much the abler of the two brothers he naturally commanded the loyalty of the young and ambitious. These men were looking to the future. By comparison, apart from Thomas of Lancaster, the King’s new ministers were very much men of the previous generation who had been sidelined during the Prince’s two-year ministry and had no reason to look forward to his accession as King.

What lay behind this clash of wills is difficult to say, but the question how to exploit the current divisions in France must have been a large part of it. At the beginning of December 1411, immediately after the dismissal of the councillors, Henry IV declared his intention once again of taking an army under his personal command to France. The Convocation of Canterbury, which was meeting at the time in St Paul’s Cathedral, was told that the campaign was expected to last six months and to cost at least £100,000. This suggests that he expected to fight for his own account and not as a mercenary for either of the rival parties in France. In the event this proved to be unaffordable. The final instalment of the previous Parliamentary subsidy, voted in May 1410, was in the process of collection but was already fully committed to the defence of the Welsh and Scottish marches. The wool subsidy was largely committed to the defence of Calais. The Commons were reluctant to grant another subsidy so soon after the last one and eventually conceded only a modest tax on incomes from land which took a long time to assess and brought in less than £1,400. The Convocations of the clergy added a half-subsidy of their own, worth about £8,000, bringing the total of new funds to less than a tenth of the estimated cost of the proposed army. By the time that Parliament dispersed on 19 December it was already clear that the only way of intervening decisively in France was to sell the services of an English expeditionary force to one of the rival parties.

The Duke of Burgundy had already prepared his bid. With the Armagnac forces dispersed and on the defensive he anticipated a campaign of sieges. His need of English troops was more modest than the year before when he had had to be ready for a pitched battle. His main purpose was to ensure that the English did not fight for his enemies. Early in December 1411 he appointed the Bishop of Arras to lead an embassy to England. He was accredited not just to Henry IV but to Joan of Navarre, Henry of Monmouth and various other English notables. The bishop was authorised to repeat the offer of the hand of John’s daughter Anne for the Prince of Wales. But the Armagnac princes were prepared to offer more. Meeting at Bourges on 24 January 1412 the Dukes of Berry, Orléans and Bourbon and the Count of Alençon named their own ambassadors and drew up their instructions. They were authorised to negotiate with ‘Henry by the grace of God King of England and his illustrious sons’, a dignity that they had never previously been willing to accord them. Their appointed spokesman was a protégé of the Duke of Berry, the Augustinian preacher Jacques Legrand. He and his colleagues were told to appeal to Henry IV’s sense of justice. He was to recount the history of the last four years since the murder of Louis of Orléans and to explain how the Duke of Burgundy had seduced the credulous inhabitants of Paris, imposed his will on the King and the Dauphin and launched a vicious campaign of persecution against his enemies. Once they had done this they were to ask to speak to the English King in private and get down to the real purpose of their visit. The Armagnac princes wanted the support of an English army of 4,000 men for service against the Duke of Burgundy. In return they were prepared to enter into a military alliance with Henry against his enemies in Scotland, Wales and Ireland and in France itself and to negotiate a permanent peace ‘on terms which would satisfy him’. These terms, it was made clear, would include large territorial concessions in the south-west. It is clear that much was left to the discretion of the ambassadors. They were supplied with blank charters already executed by the four princes and sealed with their seals.

The moving spirit behind these proposals appears to have been John Count of Alençon, who was emerging as a power in the Armagnac camp second only to Bernard of Armagnac. The 27-year-old Count had been a protégé of Louis of Orléans in his lifetime and was one of the most consistent supporters of his house after his death. ‘Without him,’ wrote his contemporary biographer, ‘the good and holy cause of Orléans could not have been sustained.’ It was Alençon who made the arrangements for getting the ambassadors to England and receiving an English expeditionary force in France. Neither the Count of Armagnac nor Charles d’Albret were present at Bourges. But Albret added his authority later, and Armagnac sent his own representative, Jean de Loupiac, who had been party to the previous attempt to raise an English army for the Armagnac cause. The Duke of Brittany was also consulted but he was as equivocal as ever. He asked Jean de Loupiac to represent his interests and sent his own agent to England as well, but neither of them seems to have had authority to commit him to anything.

The Burgundian ambassadors arrived in London at the beginning of February 1412. They were joined there by the indispensable Jean de Kernezn, who knew his way around the English court better than anyone else in the Duke’s service. The Prince of Wales took the lead in the negotiations in spite of his fall from power. Since he had conducted the negotiations of the previous year and the main point of discussion was his possible marriage with a Burgundian princess, it could hardly have been otherwise. The Burgundian emissaries were put up at Coldharbour, the grand mansion at the water’s edge just upstream of London Bridge which had recently become the Prince’s London residence. A commission dominated by his friends was appointed to treat with them there. They included Hugh Mortimer the Prince’s Chamberlain and Thomas Langley Bishop of Durham, one of the few members of his ministry to survive the recent cull. Queen Joan actively seconded their efforts. After a month of negotiation the two sides appear to have reached agreement on the despatch of another expeditionary force to fight for John the Fearless. The first troops left England to join the Burgundian army in March. There was also an agreement in principle on the Prince’s marriage to Anne of Burgundy. Then on 10 April all of these arrangements were abruptly countermanded by the King. The English troops who had already left for France were peremptorily recalled. Henry IV expected to receive a better offer.

The Armagnac ambassadors had probably sent him an outline of their proposals in advance. But they themselves nearly came to grief before leaving France. They had decided to wait before embarking on their journey until the Burgundians had left. As they waited rumours of their mission began to leak out. Setting out from Alençon in mid-March they were stopped by the bailli of Caen with a posse of soldiers as they made their cumbrous way across the plain of Maine to take ship in Brittany. The envoys made off on the bailli’s approach and escaped. But Jacques Legrand was forced to abandon his baggage, which contained copies of his confidential instructions and some of the precious blank charters. The Duke of Burgundy immediately sent out ships to patrol the Channel in the hope of intercepting the ambassadors at sea. They finally had to be collected from Brittany by a fleet of armed ships sent from England. As a result of these mishaps they did not reach London until the beginning of May. They were assigned quarters in the Dominican house at Blackfriars, where the King’s council was in the habit of meeting. There the negotiations were conducted in great haste under the shadow of the rapidly developing situation across the Channel. The documents taken from Jacques Legrand’s baggage had already been laid before the French royal council at a packed and emotional meeting in the Hôtel Saint-Pol on 6 April. Reports of their contents quickly spread through the French capital where they provoked outrage and threats of violence against real or imagined Armagnac partisans. The Duke of Berry and the Count of Alençon were held responsible. A double campaign was announced, one wing to be deployed against Alençon in the west and the other against Berry beyond the Loire. The Count of Saint-Pol left Paris a few days after the council meeting with more than 3,000 men to invade the county of Alençon. Thousands more assembled in the plain south of Paris to march on Bourges under the command of John the Fearless himself. On 6 May 1412 Charles VI, accompanied by the Dauphin, the Duke of Burgundy and a crowd of captains, received the Oriflamme from the Abbot of Saint-Denis.

At the London Blackfriars the ambassadors of the French princes believed their cause to be at the edge of the abyss. They were not inclined to haggle. They conceded everything almost at once. They agreed to the restoration of all the provinces of Aquitaine which had been ceded to Edward III and then reconquered by Charles V. The domains of the Duke of Berry in Poitou and the Duke of Orléans in Angoumois would be retained by them for life and would vest in the English Crown on their deaths. This was subject to a carve-out for the four strategic fortresses of Poitiers, Niort, Lusignan and Chateuneuf-sur-Charente which would be ceded to Henry IV at once. Twenty other major royal fortresses of Aquitaine were identified for immediate transfer to the English King’s representatives. Some 1,500 others belonging to the Armagnac princes and their followers would be held by them as vassals of the King of England. The thorny question of the feudal status of Aquitaine was left vague. The treaty merely provided that Henry and his heirs would hold the enlarged duchy ‘as freely as any of his forebears had held it’, which was itself a contentious issue. In theory, however, these remarkable proposals gave the English at a stroke most of what they had fought and argued for in vain for the past forty years. In return, all that was required of them was an army of 1,000 men-at-arms and 3,000 archers for three months. The entire cost was to be met from the coffers of the Armagnac princes from the time that the army reached the appointed meeting place in France. There was initially some doubt about where this meeting place would be. Until a late stage of the negotiations it was assumed that the English expeditionary force would sail for Bordeaux and join forces with the Armagnac princes on the Gascon march, in Poitou or the county of Angoulême. This plan was never realistic. The shipment of 4,000 men with their hangers-on, horses and equipment round the Breton cape would have required more ocean-going ships than England had available and cost more than Henry IV could afford. By the time the terms were finalised it had been overtaken by events. The Armagnac positions in Poitou and Angoulême had collapsed and attention had shifted to the defence of the princes’ domains in Berry and the Loire. So it was agreed that the English army would meet the princes at Blois, a town on the Loire belonging to Charles of Orléans with an important stone bridge.

Henry IV was highly satisfied with the terms. According to the chronicler Thomas Walsingham, when his councillors told him what was on offer he rose from his seat, clapped his hands in delight and said to Chancellor Arundel: ‘Now is the time to enjoy God’s bounty and by this simple negotiation to enter France and resume our rightful inheritance.’ The agreement is commonly known as the treaty of Bourges, which is the place given in the text. But its terms were in fact transcribed in England onto the forms which the four leading Armagnac princes had signed and sealed in blank at Bourges before their envoys left France. Bernard of Armagnac and Charles d’Albret had not executed the blanks and so their representatives made separate declarations on their behalf. The counterparts were formally exchanged in London on 18 May 1412. The Prince of Wales had had nothing to do with any of this and was palpably embarrassed. He addressed an apologetic letter to the Duke of Burgundy explaining what had happened. He would personally have preferred to proceed with the agreement reached with his ambassadors in February, he wrote. But the decision was not his and the Armagnacs had made offers which his father had found impossible to refuse.

By the time that the English had reached agreement with the Armagnac princes the campaign in France had already begun. From the outset the Armagnacs put up a much more vigorous defence than even they had expected. The first clashes occurred in the west. The Count of Alençon’s domains in Lower Normandy and Perche were the target of coordinated offensives from two directions. The Count of Saint-Pol marched across the region at the end of April 1412 and laid siege to the ancient but powerful fortress of Domfront. The Duke of Anjou, who had been promised the lands of the house of Alençon as his reward, joined him there. John of Alençon, his forces vastly outnumbered, retreated into Brittany while his lands were wasted by his enemies. Yet his followers fought back vigorously as they had the year before. Saint-Pol and his captains took three of the Count’s castles including his magnificent mansion at Bellême, but failed to dislodge the determined garrison of Domfront. They made no attempt on the principal walled towns. One of Saint-Pol’s lieutenants approached the walls of Argentan, then ‘looked at it from afar and withdrew’. The one notable success of their campaign was the defeat of Raoul de Gaucourt, one of Charles of Orléans’ most experienced captains, who had been sent with 800 men-at-arms to support the defence. Gaucourt’s force fell into a dawn ambush near Saint-Rémy-du-Val on 10 May 1412 and was almost entirely wiped out in an exceptionally brutal battle. The incident represented a loss of face for the Duke of Orléans and earned Saint-Pol a hero’s welcome when he returned to Paris a few days later. But he had actually achieved very little. As soon as he withdrew the Count of Alençon returned from Brittany with Arthur de Richemont and some 1,600 Breton men-at-arms. They installed themselves around the Count’s capital at Alençon, re-established the Count’s authority in the region and waited for the expeditionary force from England.

This brief campaign marked a fresh landmark in the embitterment of the French civil war as old friendships were broken beyond repair and families were irretrievably divided. Gilles de Bretagne had been present at the angry council meeting in Paris when Jacques Legrand’s captured papers had been read out at the moment when his elder brother Arthur de Richemont was recruiting troops to fight the Burgundians in Normandy. They exchanged ‘high words’ when Gilles visited his brother in the hope of detaching him from the Armagnac cause. At Saint-Rémy men fought against their fathers and brothers. Jeannet de Garencières, who had been Louis of Orléans’ godson, fought with the Armagnacs. When his father, who was on the other side, recognised him among the prisoners he had to be restrained from killing him.

The main objective of the Burgundians in the summer of 1412 was to deal with the Duke of Berry, who had shut himself behind the walls of Bourges. Believing that he was the animating spirit behind the Armagnac coalition, the royal council had resolved to accept nothing less than his unconditional surrender. Their army, which had mustered outside Melun, began its march south on 14 May 1412. It was accompanied by the King, the Dauphin, the Dukes of Burgundy and Anjou, the Provost of Paris Pierre des Essarts, and the official historiographer, Michel Pintoin of Saint-Denis. At its highest point the payroll strength was about 7,000 men-at-arms and 1,200 bowmen representing a total of at least 15,000 fighting men when the gros varlets and other low-grade combatants are included. Although the royal council had expressed great indignation about the Armagnac plans to hire mercenaries from England, their own troops included at least 300 English archers who had either stayed behind after the departure of the Earl of Arundel or enlisted later in defiance of Henry IV’s commands. There was also a corps of 500 Scots, four-fifths of them archers. Every attempt was made to maintain the pretence that this was the King’s army under the King’s command. Charles VI was barely fit enough to ride. But John the Fearless needed his symbolic presence and insisted on his taking his position at the head of the van. The army marched across the open plain of the Gâtinais into the county of Nevers and at the end of May crossed the Loire into Berry by the great stone bridge at La Charité-sur-Loire.

Paris was in a state of high excitement. The citizens believed that if the Burgundians were defeated the Armagnacs would exact a terrible revenge on them for the violence done to their supporters. They had the Oriflamme that had been unfurled at the battle of Roosebeke in 1382 brought into the city from Saint-Denis along with all the most holy of the abbey’s relics. On 31 May, after the news had arrived of the crossing of the Loire, the friars of the Franciscan and Dominican convents took the famous relic of the True Cross from the Sainte-Chapelle and processed through the capital followed by the entire corps of the Parlement walking two by two in their robes of office and an estimated 30,000 citizens in their bare feet. The University viewed current events with special anxiety. They had been uncompromising in their support of John the Fearless and had a great deal to lose. When a few days later they organised their own procession, the line of robed academics, students and schoolchildren with candles in their hands snaked through the city for eight miles from the convent of the Mathurins on the left bank to the abbey of Saint-Denis beyond the northern gates. These immense processions, at once political demonstrations, invocations of the Almighty and exercises in communal solidarity, were organised every day during the King’s absence with the army and would become a regular feature of Parisian life in the years of crisis to come.