From 1916 Supermarine Aviation continued the business, formerly carried out by Pemberton Billing, at premises alongside Southampton’s Woolston Ferry, with Hubert Scott-Paine as Managing Director. Their early motto was ‘a boat that will fly, rather than an aeroplane with floats’. During the latter stage of the First World War the company had been building AD patrol flying boats for the Royal Naval Air Service. Problems over their engines meant that only a few had been delivered by the end of the war. With the return to peace a number were purchased by Supermarine and converted for civilian use as Supermarine Channels. They were equipped with more powerful 160-hp Beardmore engines and able to carry three passengers in the nose, forward of the pilot. The disadvantage for these early travellers was that all the seats were exposed to the elements. An initial batch of ten Channels was registered by Supermarine in June 1919 (G-EAED–EM). Three gained passenger-carrying Certificates of Airworthiness at the end of July and were put into service by Supermarine carrying out joy flights from alongside Bournemouth Pier, still wearing their former military markings.

Of the initial Channels three others were sold to Norway, followed by the final three to Bermuda in April 1920. The Norwegian ones were operated by Norske Luftreideri during 1920 on mail services between Bergen and Stavanger. G-EAEF/EG/EJ were shipped to Bermuda for operations with Bermuda and Western Atlantic Aviation Co., mostly used for joy flights. Services in Norway and Bermuda only lasted a few months, having to close down mainly due to the lack of available spares. A further batch of four was purchased by the Royal Norwegian Navy in the spring of 1920, with one used as a trainer. Supermarine then produced a batch of nine Channel IIs powered by 240-hp Siddeley Puma engines. These all ended up being exported to such far-flung places as Chile, Cuba, Japan and New Zealand. G-NZAI was used by the New Zealand Flying School and operated the first flight between Auckland and Wellington in October 1921.

Following on from the Channels, Supermarine produced a number of amphibians, which resembled the earlier aircraft in general shape, all having pusher engines. These included the Sea Lions produced for the Schneider Trophy Races of 1919, 1921 and 1923 and the Sea Kings, which replaced the Channels on services from Southampton to Woolston. The Sea King was then developed into the Seagull which first flew in May 1921. In 1922 Supermarine received an initial order from the Navy for eighteen Seagull II amphibians in order to keep the company in business during a lean period. The type was also operated by the Royal Australian Air Force from its one and only aircraft carrier and a couple were operated as civil aircraft on joy flights out of Shoreham. Production of the Seagull enhanced Supermarine’s name. As a result the Air Ministry ordered a large experimental reconnaissance flying boat from Supermarine – the Swan. Flown in March 1924 as N-175, successful military trials were undertaken at Felixstowe, resulting in an order for six similar aircraft – the Southampton, which entered RAF service in September 1925. As with previous Supermarine aircraft, these were fitted with wooden hulls. But an additional Southampton was ordered and fitted with a metal hull, so becoming the Southampton II. Wooden hulls always tended to become waterlogged and the metal hulls did away with this, as well as proving lighter. After successful trials, seventy-nine Southamptons were eventually ordered and, as well as lengthy service with the RAF, they served with the Argentinian and Turkish navies. The RAF obtained great publicity with a Far Eastern and Australian tour undertaken by four Southamptons during 1927/28. Departing from Plymouth in the autumn, they slowly made their way out to Singapore and then undertook a tour around Australia. They eventually returned to Singapore – their new base – in December 1928. The 27,000-mile tour demonstrated the reliability and safety of the flying boat. Swan N-175 was converted as a civilian aircraft in the spring of 1926 and flown in June as G-EBJY. Ten passengers were accommodated in wicker armchairs within the spacious cabin and the Swan was loaned to Imperial Airways in 1927 for use on its Southampton–Channel Islands services.

In January 1927 Supermarine underwent financial reorganisation. This was a prelude to obtaining additional production space in the spring by taking over the disused Admiralty sheds at Hythe on the opposite side of Southampton Water. Then in November 1928 Supermarine was acquired by Vickers (Aviation) Ltd of Weybridge, with production continuing at Woolston and Hythe as the Supermarine Works of Vickers (Aviation) Ltd, more frequently referred to as Vickers-Supermarine.

Supermarine’s main fame at this time was the series of successful racing seaplanes it built for the Schneider races. These monoplane racers were built as small as possible for the size of engine fitted and, despite the large twin floats, were capable of very high speed. Commencing in 1925 with the S.4, the racers developed into the S.6B of 1931, which succeeded in winning the Schneider Trophy for Great Britain for all time. Later that year it pushed the World Air Speed Record to 407.5 mph. These racing Supermarines were operated by the RAF’s High Speed Flight.

Supermarine also managed to become involved in luxury civilian flying boats. In the summer of 1926 the Danish Navy ordered a three-engined version of the Southampton – the Nanok. This was flown in June 1927, but its performance was not up to expectation, so the Danes refused to accept the aircraft. After a period of storage Supermarine were able to sell the Nanok in 1928 as an air yacht to the Hon. A. E. Guinness (of Guinness Brewery fame) for flights between his homes in Hampshire and Galway as well as the family business in Dublin. Now known as the Solent, the aircraft was fitted with twelve luxury seats and was a frequent visitor to Hythe. Supermarine then proceeded with a much larger flying boat for the Hon. Guinness. The design originated as an angular-shaped monoplane reconnaissance flying boat for the RAF, fitted with sponsons and not underwing floats. However the aircraft was considered too large for military use, so it was modified with a luxury interior including ten beds. Built at Hythe as the Air Yacht, it had a span of 92 feet and was powered by three 490-hp AS Jaguar engines. Registered as G-AASE it flew in February 1930 and underwent prolonged trials, which lasted almost eighteen months. During this time it was re-engined with three 525-hp AS Panthers to try and improve its performance. Trials had shown that the Air Yacht needed a long take-off run and its cruising speed was only just over 100 mph. By the end of 1931 it had been rejected by the Hon. Guinness as unsatisfactory for his needs and was placed into storage. Eventually it was sold in the autumn of 1932 to an American millionairess for use as luxury transport. However its active days were few as it was damaged beyond repair in an accident off Capri in January 1933. In 1928 Supermarine designed an enormous flying boat for the RAF, but it was turned down. However the plans evolved as the civilian Type 179 whose prototype was ordered in March 1930. Intended as a forty-seat luxury transport, some of the accommodation was provided in its wings. Initially planned to be powered by six Rolls-Royce engines, and with a span of 185 feet, the 179 soon became known as the Giant. The fuselage was built at Woolston, but frequent changes in official requirements necessitated numerous redesigns to the wing and engine layout. These delayed construction and in the end the 179 was cancelled by the Government in January 1932 as an economy measure.

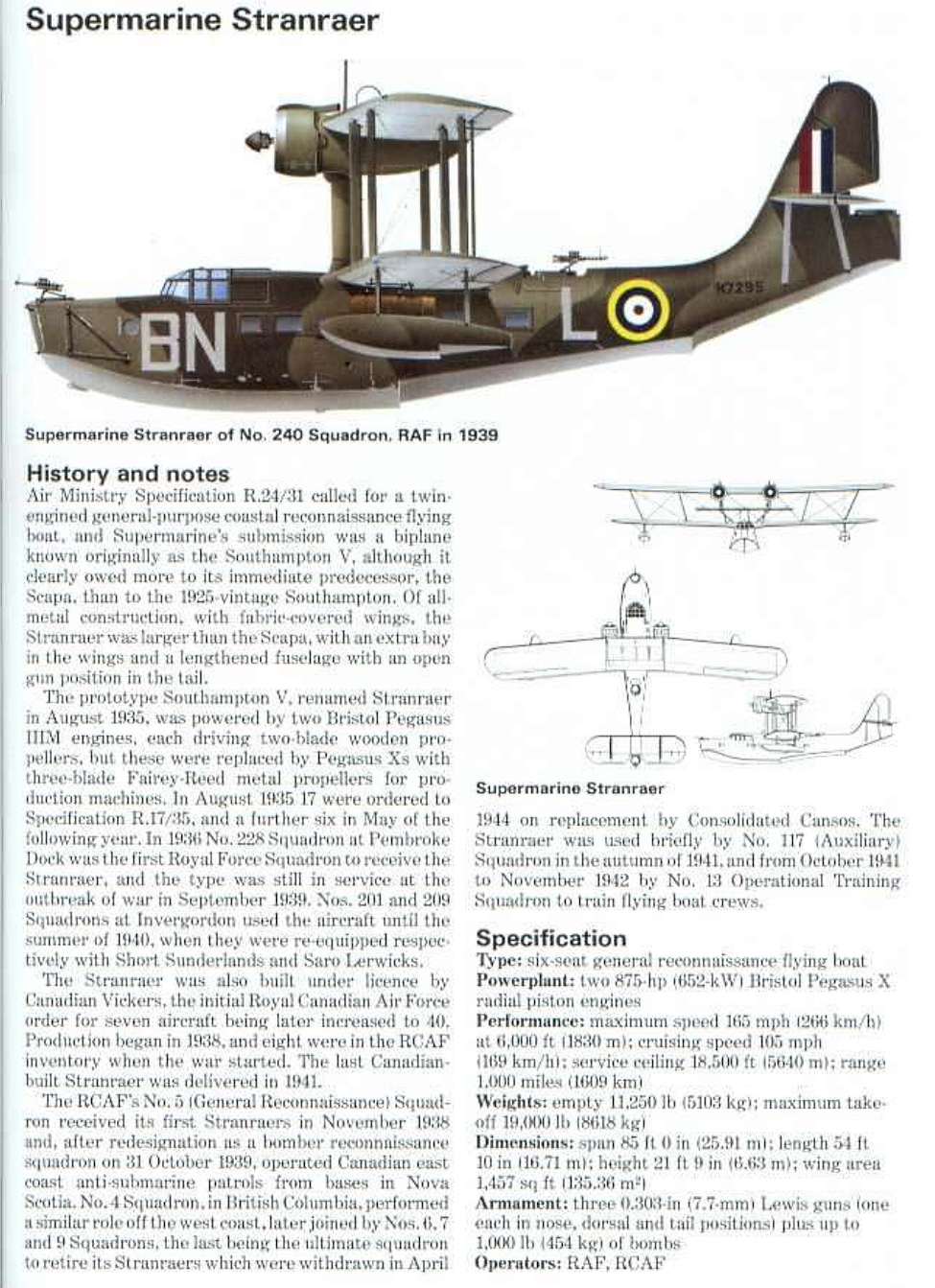

Due to the success of the Southampton in RAF service, Supermarine developed the design as the Improved Southampton IV, with prototype S1648 flying in July 1932. Renamed the Scapa in October 1933, it was still a twin-engine biplane (Rolls-Royce Kestrels), but the pilots were now seated in an enclosed cockpit. Fifteen were completed for the RAF at Supermarine’s Hythe works. Three still remained in a training role on the outbreak of the Second World War. The company’s flying boat finale came with the Stranraer which was built to replace the Scapa. Powered by two Bristol Pegasus engines, it still retained the classic 1920/30s flying boat shape and was produced to the same RAF requirement as the Saro London. The prototype Stranraer K3973 flew from Woolston in July 1934, with production versions entering service in a reconnaissance role from April 1937. It soon proved to have excellent performance and seaworthiness. As they were intended for long-range flights, the aircraft included cooking and sleeping facilities for the crew of five. The final Stranraer entered RAF service in April 1939, by which time the day of the biplane flying boat had passed – the Sunderland having entered service in June 1938. Forty Stranraers were also built by Canadian Vickers from 1937 for the Royal Canadian Air Force, with some remaining in airline service in the 1950s. With an increasing order book by 1937 (Stranraer, Walrus, Spitfire) Supermarine needed to build an additional factory just upstream from Woolston, known as the Itchen works. The final Stranraers were built at Itchen, along with early production Spitfires.

So ended Supermarine’s line of flying boats, although two amphibious designs saw successful wartime service with both the RAF and Royal Navy. These were the elderly Walrus and its replacement, the Sea Otter. Both types became well known as air sea rescue aircraft, the Sea Otter remaining in service until the early 1950s when it was replaced by helicopters. Of course, Vickers-Supermarine had other important wartime work to keep the factories busy – the development and production of Spitfire fighters.