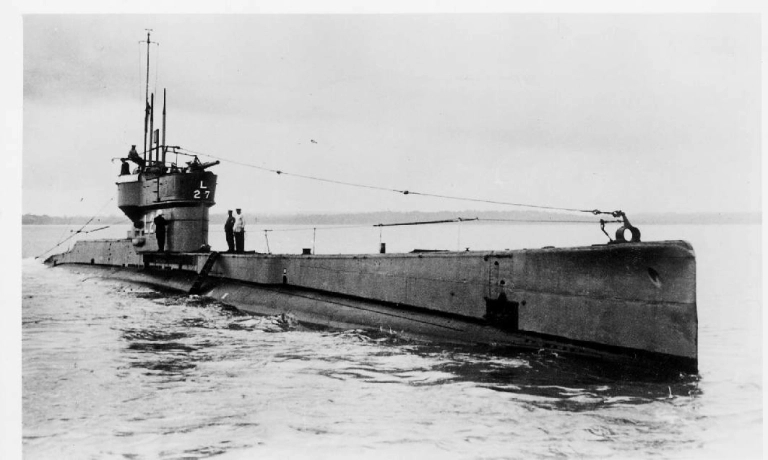

4th June 1919 – British submarine ‘L.55’ (1918, 960t, 6-21in tt, 2-4in). With the British Baltic Squadron blockading the Bolshevik naval base of Kronstadt on Kotlin Island laying off Petrograd, warships on both sides were lost. On the 4th (some accounts say the 9th) ‘L-55’ was in action with Russian patrols and sunk by the gunfire of destroyers ‘Azard’ and ‘Gavriil’. She is later raised and commissioned into the Soviet Navy as ‘L-55’

At the outset of war in 1914 the Baltic Sea was effectively closed to the Royal Navy, with its only presence being affected by a British submarine flotilla of initially six E class boats that entered the Baltic covertly to co-operate with the Russian Baltic Fleet based at Kronstadt. The Russian Baltic Fleet at the beginning of the war was greatly inferior to the German High Seas Fleet, where the German commander Admiral Erhard Schmidt could call on modern dreadnought battleships and battle-cruisers that could be quickly transferred from their bases on the North Sea coast to the Baltic via the Kiel Canal, which could just as easily be returned to the North Sea should the tactical situation demand it.

In August 1915 the Russian fleet commander Admiral Vasily Kanin had at his disposal in the Gulf of Riga the 14,450 ton pre-dreadnought battleship Slava, with a main armament of only two 12in and twelve 6in guns – a Borodino class ship similar to the four battleships that had been sunk by the Japanese at the Battle of Tsushima in 1904. Also available to him were four small 1,700-ton gunboats, a minelayer and a flotilla of sixteen destroyers.

Early in August 1915, powerful units of the High Seas Fleet entered the Baltic with the intention of conducting a foray into the Gulf of Riga in support of German troops advancing from the south through Courland and to destroy the Russian naval forces stationed in the Gulf, including the Slava, and to capture the port of Riga.

On 8 August the German force comprising two dreadnoughts Nassau and SMS Posen of 18,600 tons, armed with twelve 11in guns and two pre-dreadnoughts, SMS Braunschweig and Elsass, mounting four 11in guns apiece and supported by four light cruisers and no less than fifty-six torpedo boats, attempted to break through the extensive minefields that protected the entrance to the Gulf.

At the same time the German fleet was further reinforced by the battle-cruisers Moltke, Von der Tann and Seydlitz commanded by Vice-Admiral von Hipper, who temporarily took over the command of the operation.

The two German pre-dreadnoughts engaged the Russian battleship Slava to allow the minesweepers to clear safe channels into the Gulf while the minelayer Deutschland was sent to mine Moon Sound to the north between the mainland and the islands of Hiiumaa and Saaremaa.

Despite their overwhelming superiority, the German forces were unable to clear the minefields and retired, making a second attempt on 16 August, when they lost the minesweeper T46 and the torpedo boat V99. But in return they managed to damage the Slava and successfully cleared the minefields by 19 August, which allowed the German ships into the Gulf to attack the shore installations.

However, before this could be accomplished, reports of British and Allied submarines operating in the restricted waters of the Gulf caused the German ships to withdraw, which demonstrates the influence a handful of British submarines could exert on naval operations in such enclosed waters.

Vice-Admiral von Hipper’s battle-cruisers continued to operate in support of the army assault on Riga, when early on the morning of 20 August the Seydlitz was struck by a torpedo fired from the British submarine E1 commanded by Lieutenant Noel Laurence.

The torpedo struck the forward torpedo flat at the bow, but failed to detonate the stored torpedoes. However, the ship was sufficiently badly damaged to need repair at the Blohm & Voss yards in Hamburg, lasting until the end of September.

The E1 together with E9, commanded by Max Horton, had entered the Baltic on 15 October 1914 and based at Reval (modern Tallinn) in Estonia. The six E class submarines were joined by five of the earlier and smaller C class which had been shipped to the White Sea and transported by canal to Kronstadt where, as described earlier, they severely curtailed the iron ore trade between Sweden and Germany, as well as restricting German naval operations and training in the Baltic, which previously had been a German lake.

On the night of 18 October 1914 the E1 penetrated Kiel Bay and attacked the armoured cruiser SMS Victoria Louise, firing a single torpedo, which ran too deep, passing under the ship’s keel. This demonstration of British sea power reaching into the home of the German fleet in the Baltic caused the Kaiserliche Marine to be ever more cautious.

The E13, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander Geoffrey Layton, was accompanied by the E8, which safely made the passage, while E13 transiting the Danish Straits on 13 August 1915 became stranded on Saltholm Island south of Copenhagen.

At first light, the stranded submarine was spotted by Danish naval forces, who sent torpedo boats to investigate; these were later reinforced by the coast defence ship Peder Skram to ascertain the nationality of the vessel.

At the same time German torpedo boats also had the E13 under observation, as orders from the Danish naval Chief of Staff were received by the captain of the Peder Skram that he was to forestall any attempts by the Germans to seize or attack the British submarine. At 6.00 a.m. the Danish torpedo boat Storen reported two German torpedo boats passing close to the scene, followed by extensive wireless traffic.

Later, at 10.28 a.m., two German torpedo boats, G132 and G134, approached at high speed while flying the international abandon ship flag signals, and when within range, the G132 fired a single torpedo, which missed and exploded on the sea bed.

The Danish warships made no move to interfere and both German ships opened a rapid fire with deck guns on the helpless submarine that lasted less than 5 minutes, leaving the E13 on fire, with poisonous chlorine gas spreading through the hull. Lieutenant Commander Layton ordered abandon ship and fourteen crew members including the commander were taken off by the torpedo boat Storen, leaving fifteen dead, whose bodies were later recovered and returned to England.

The failure of the Danish ships to protect the E13 despite being ordered to protect her with all means at their disposal had allowed the Germans to carry out this attack.

The surviving crew were taken into internment for the duration, but Lieutenant Commander Layton and his first officer escaped to rejoin the fleet and the wreckage of E13 was later raised and scrapped.

The E18 and E19 arrived safely at Reval on 15 September 1915. On 10 October the E19 under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Francis Cromie, patrolling south of the Swedish island of Oland in the early hours of the morning, spotted a German steamer, the SS Walther Leonhardt, carrying iron ore which, after being ordered to heave to and the crew taking to the boats, was sunk by an explosive charge.

Later that morning a second steamer, the SS Germania, also carrying iron ore, was sighted and attempted to escape, being pursued by E19 on the surface at 15 knots while firing her deck gun. The German ship eventually ran aground and a dynamite charge was laid which, although damaging the vessel, failed to sink it, and it was subsequently repaired.

After midday a third ship, the SS Guntrune, was boarded and, after the crew were in lifeboats, she was sunk by opening the seacocks. Immediately following this, another ship, the SS Director Repperhagen, was also sunk and finally at 5.30 p.m. the same day a fifth victim, the SS Nicomedia – whose crew, as they took to the boats, presented the British submariners with a barrel of beer – was sent to the bottom.

In a single day E9 had sunk four ore carriers and wrecked another ashore without the expenditure of a single torpedo.

Later, on 7 November 1915, the E19 patrolling off Cape Arkona on the Baltic island of Rugen fired two torpedoes at the light cruiser HMS Undine of 3,110 tons, causing her magazine to explode, but fortunately with the loss of only fourteen crew members.

This loss came only two weeks after the sinking of the 9,800-ton armoured cruiser SMS Prinz Adalbert off Libau on 23 October by the E8, resulting in a heavy loss of life. This, together with the loss of the 3,750 ton light cruiser SMS Bremen to a Russian mine in February 1915, served as a further demonstration of the positive effect the British submarine flotilla was having on the German ability to operate safely within the Baltic.

The E18 under the command of Lieutenant-Commander R. Halahan, which had arrived at Reval on 18 June after being fired on by German cruisers during her passage, conducted four patrols, before being lost in June 1916, presumably to a mine in the eastern Baltic.

Much later in 1918 the E1, E8, E9 and E19 were scuttled outside Helsingfors in the civil war between the Bolsheviks and White Russian forces.

The four earlier C class submarines C26, C27, C32 and C35 of 290-ton surface displacement due to their short range were towed from Britain via the North Cape to Archangelsk in the White Sea. From there they were transported on barges through the White Sea canal, reaching St Petersburg in September 1916. But due to the lateness of the season and heavy ice they were not able to operate until the Spring of 1917.

The C32 became stranded in the Gulf of Riga and had to be abandoned, while the remaining three C class boats were blown up at Helsingfors to avoid capture in 1918.

An incident of the greatest significance to the conduct of the war took place on 25 August 1914 when the German light cruiser SMS Magdeburg of 4,500 tons ran aground on the island of Oldensholm off the Estonian coast while conducting a sweep with other ships in the Gulf of Finland. This ship had previously fired the first shots of the Great War when on 2 August 1914 the Magdeburg shelled Russian positions in the port of Libau. Two Russian cruisers opened fire on the stranded ship, which was badly damaged, causing the crew to be evacuated, after giving up attempts to re-float the ship.

Subsequently, after the German forces had been driven off, Russian divers were able to recover German naval and merchant code books then in use, which also revealed the methods employed for constructing future codes, which once delivered to the Admiralty cryptographers in London enabled the Admiralty to decipher almost all of the German wireless traffic for the remainder of the war.

In the land war, unlike the trench warfare that had prevailed in the west from Nieuport on the coast of Belgium to the Swiss border for the past four years, on the Eastern Front the war was a more mobile affair.

Initially, the Russian troops enjoyed brief success, advancing into Austrian territory, but were heavily defeated by the Germans at the Battle of Tannenberg in late August 1914.

In early 1915 the Allies attempted to relive the pressure on the Russians by attacking Turkey with a landing at Gallipoli, which as we have seen was a costly failure, and did little to help the situation on the Eastern Front.

The strain on Russia, a poorly governed and bankrupt country, was made worse by further defeats in the field, mutinies in the army and strikes and food riots in a civilian population living on the verge of starvation.

Political agitators of all colours appealed to the masses and a disaffected army to withdraw from the crippling war – a situation that led to further mutinies, civil unrest and finally the revolution of February 1917, which forced Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate in March, allowing for the formation of a democratic provisional government.

This was a coalition under the leadership of Alexander Kerensky, who represented the moderate socialists, working together with the Soviet workers’ councils or Bolsheviks. Once installed, the Duma or parliament, assured the Allied powers that it intended to continue to prosecute the war against Imperial Germany on the Eastern Front.

In return for this promise, the Allies, including the United States, which had just entered the war in April 1917, increased proportionally the supply of war materials and economic aid, with large convoys of merchant ships carrying thousands of tons of military supplies and munitions to the vast warehouses in Archangel and the ice-free port of Murmansk, where due to the complicated bureaucracy of army it piled up largely unused. Plagued by further mutinies and mass desertions, the major Russian offensive of June 1918 was a failure and was in turn crushed by the German counter-offensive.

Finally, in October 1917, following food riots in St Petersburg, the Kerensky Government was overthrown by the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, establishing a Communist government determined to end their part in the war. This was followed 5 months later in March 1918 by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which was signed with Germany, formally ending the war on the Eastern Front.

With the treaty the Russians temporarily surrendered a vast swathe of territory, including the Crimea to the Germans.

The signing of the treaty allowed the Germans to withdraw a large number of troops and re-deploy them on the Western Front, where they launched their last great offensive, which was doomed to failure as the Allies strengthened by fresh American troops counter-attacked in July 1918, throwing the Germans back, breaking their line in September 1918. While in the south the Italian Army defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto and the war was almost at an end.

At home the civilian population were suffering terrible privation as a result of the British economic blockade and, following mutinies in the High Sea Fleet in October 1918 when they refused orders to put to sea to engage the Grand Fleet, hoping for a victory that would put Germany in a better negotiating position at the now inevitable cessation of hostilities, the German general Staff sued for peace, obtaining an armistice on 11 November 1918.

Before this, however, and worryingly for the Allies, in April 1918 a division of German troops had landed in southern Finland, this being part of the territories ceded to Germany under the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, creating the fear that the Germans might seize the important railway between Petrograd (as St Petersburg had been renamed) and the strategic seaport of Murmansk, threatening the vast stores of stockpiled war materials.

Coincidently, a civil war had broken out in Russia between the Bolsheviks (the Reds) and those still loyal to the Tsar and the monarchy (the White Russian forces or the Whites).

Into this confused situation the leaders of the British and French governments concluded that the western Allies should conduct a military intervention in north Russia with the three following objectives:

1. To prevent the large stockpile of Allied military materials from falling into the hands of either Bolshevik or German forces.

2. To rescue the Allied Czechoslovak Legion stranded along the Trans-Siberian Railroad, after being promised safe passage to the west from Vladivostok and later rescinded by the Bolsheviks.

3. To defeat the Bolshevik Army with the aid of the Czechoslovak Legion and thereafter with the assistance of White Russian forces continue the war against Germany on the Eastern Front.

Other Allied objectives included to contain and defeat the rise of Bolshevism and to encourage the independence of the Baltic states from Russia.

The North Russian Expeditionary Force constituted in July 1918 consisted of some 15,000 British, French, American and Canadian soldiers and artillery. They were landed at Archangelsk, with the Allied forces occupying the port supported by a Royal Naval flotilla of more than twenty ships, which included the seaplane carriers HMS Pegasus and HMS Nairana.

The Allied troops, including Polish and White guard units, advanced down the Vaga and northern Dvina rivers into territory held by Red forces, capturing key points up to 150 miles south of Archangel. In this offensive they were supported by a force of eleven river monitors, minesweepers and White Russian gunboats.

These ships varied in size and armament but were generally of 540 tons’ displacement and mounted a single 9.2in and a 3in gun, performing valuable service on the navigable sections of the rivers. Nonetheless, Bolshevik gunboats, torpedo armed launches and mines took a steady toll on the Royal Naval flotilla.

On 18 September 1918, Bolshevik troops attacked the British Embassy in St Petersburg, sacking the building and killing the staff, including British Naval Attaché Captain Frances Crombie, whose body was mutilated by the attackers.

The initial Allied gains along the northern rivers and around Lake Onega were short-lived as the Bolsheviks gradually gained the upper hand, with more heavy artillery being used against Allied forces in the fierce fighting that caused the Allies to retreat from the Varga River during September, with the monitors making their final attack on the Red gunboats that month before withdrawing.

The final battles of the northern campaign were fought between March and April 1919 when, due to the inability of the Allies to hold the line and mutinies in the White Russian forces, the Allies withdrew from the northern theatre.

The last Royal Naval losses on the Dvina River was that of the monitors M25 and M27, each of 540 tons. On 16 September, due to a fall in the river level, the two monitors were trapped, unable to join other ships of the Northern force, and they had to be blown up to avoid them falling into the hands of the Reds.

Earlier, in June and July 1919 respectively, the armed trawlers HMS Sword Dance and Fandango were lost to mines on the Dvina River.

In the south the Allied intervention commenced immediately following the armistice and now that the Royal Navy had access to the Baltic. A powerful squadron of C class cruisers, V and W class destroyers and seaplane carriers was dispatched, initially under the command of Rear Admiral Alexander-Sinclair, but replaced in January 1919 by Rear-Admiral Walter Cowan, with Tallinn as their base.

The British squadron used their guns to bombard Bolshevik positions while supporting Latvian and Estonian forces, who had declared their independence from Russia along with Lithuania in November 1918.

The British ships had also severely curtailed the activities of the Russian Bolshevik fleet, effectively trapping them in their base at Kronstadt. During the course of these actions the 4,100 ton cruiser HMS Cassandra, armed with five 6in guns, while on operations against enemy positions, was mined and lost in the Gulf of Finland, fortunately with a minimum loss of life.

On 26 December 1918 the cruisers HMS Caradoc and HMS Calypso and four destroyers were supporting Estonian troops off Tallinn when they fired on two Bolshevik destroyers, the Avtroil and the Spartak, that had been shelling the port, with the Russian ships surrendering without reply to the British salvoes. The two captured ships were handed over to the Estonian Provisional Government where they were incorporated into the nascent Estonian Navy.

The situation in the eastern Baltic following the armistice of 11 November 1918 was a confused one. German troops had earlier in 1917 taken Riga after much fierce fighting, and the German Freikorps, together with the ethnic Baltic German Landeswehr troops, were still fighting against the Russians and newly established local Estonian National Army units, who in turn were fighting against the Red Army, and, as mentioned earlier, German troops had occupied southern Finland in April 1918.

Throughout the summer of 1919, while the Royal Navy kept the Bolshevik fleet largely contained in Kronstadt harbour, occasional sallies were made by the Reds. One such attack was when the battleship Petropavlovsk (not to be confused with an earlier ship of the same name that was lost at Tsushima in 1904), a modern dreadnought of 24,000 tons mounting twelve 12in guns, probed the British base at Tallinn on 31 May, scoring a hit on the destroyer Walker, which perversely persuaded Admiral Cowan to move his base closer to Kronstadt.

From their new base at Vantaa on the coast of southern Finland on 17 June, a flotilla of fast Coastal Motor Boats (CMB) attacked the harbour of Kronstadt, where, for the loss of three CMBs, the flotilla sank the light cruiser Oleg and an accommodation ship, as well as damaging two battleships with torpedoes.

One of the battleships damaged was the dreadnought Petropavlovsk, which was struck by two torpedoes, causing her to sink. Due to the shallow water, she was later raised and repaired.

The British CMBs were in action both in the Baltic and in the northern Russian river systems and the Caspian, where they took a steady toll on Bolshevik shipping. They had originally been designed in secret with stepped hydroplane hulls, incorporating chine to reduce and deflect bow spray, and were to be employed in attacking enemy ships at anchor in their harbours, where their small size, speed and shallow draft would in turn make them difficult targets to hit and allow them to pass over defensive minefields to press home their attacks.

Of the four CMBs that took part in the action on Kronstadt naval base, the CMB 88 is typical of the type. Built in the Thornycroft yard on the River Thames, she was 60ft overall, with a beam of 11ft, and displaced 11 tons. She was powered by two petrol engines with a combined 900hp on two screws, giving a speed of 40 to 42 knots.

She carried a complement of five and was armed with four Lewis machine guns and two 18in torpedoes. Once the CMB was heading at speed directly towards the target, the torpedo was launched with the engine running from a trough at the stern. As soon as the torpedo was running on course the CMB would turn aside to get out of its way.

Other Royal Naval ships were sent to the Baltic, including the aircraft carrier HMS Vindictive. This was a converted heavy cruiser of 9,340 tons’ displacement, with a flying-off deck forward of the funnel superstructure and landing-on deck aft, similar to the much larger Furious.

She was equipped to carry six aircraft that were employed to carry out bombing and strafing attacks on gun and searchlight emplacements on the Kronstadt naval base. Also, in the Autumn, the force was further strengthened by the arrival of the monitor HMS Erebus, a powerful vessel of 8,000 tons’ displacement and armed with two 15in guns that were used to effect in support of the White Russian Northern army’s offensive against Petrograd.

On 16 July two British minesweepers, HMS Myrtle and HMS Gentian, were lost off the island of Saaremaa to mines. These two ships were Flower class sloops, of which seventy-two were built. Designed on merchant ship lines with no frills, they were completed within a six-month building period.

Initially designed as minesweepers, these handy vessels performed other duties, with thirty-nine being completed as Q ships. They were also employed on convoy protection and anti-submarine work, armed with depth charges.

The typical Flower class sloop was of 1,200 tons’ displacement, with a length of 262ft on a beam of 33ft. Engine power was provided by a four cylinder triple expansion steam engine of 2,400hp on a single shaft, giving a speed of 15 to 17 knots.

Two other losses were those of the destroyer HMS Verulam, mined in the Gulf of Finland on 1 September 1919, and the destroyer HMS Vittoria, which was torpedoed by the Bolshevik submarine Pantera off the island of Seiskarin, this being the only success achieved by a Russian submarine in the conflict.

The Tsarist Russian Navy also conducted operations in the Black Sea against the Bolsheviks, without British assistance, while an even smaller group of British ships, supported with supplies and ammunition through Persia, operated on the land-locked Caspian Sea.

The Royal Navy put together an improvised flotilla of gunboats from commandeered local craft mounting 4in and 6in guns, which were active against the Red forces consisting of four old destroyers that had been sent from the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea via the Volga River into the Caspian, together with the fairly modern (1906) destroyer Moskvitann of 510 tons that carried two 12pdr guns and three torpedo tubes.

In an action between the Royal Navy scratch flotilla and the Bolshevik destroyers off Alexandrovsk, all the Russian Bolshevik ships and the Moskvitann were sunk or severely damaged.

At the beginning of the intervention in July 1918 some fourteen Allied countries including Japan, Italy and Portugal were involved. Britain and France, desperately short of soldiers for the Western Front, asked the United States to supply troops, which President Woodrow Wilson acceded to despite the misgivings of the State Department, who were very much against using American troops to support a despotic and undemocratic country such as Tsarist Russia, although at the same time they were alarmed by the equally ruthless alternative represented by the Bolsheviks, who threatened the capitalistic democracies through world revolution.

The long campaign was brought to an end by the White Russian forces being unable to contain or defeat the growing Bolshevik armies, who were gaining territory and forcing the White Russian armies to retreat into an ever smaller area of Russia that was under their control. Further defections and mutinies hastened the process and there were even minor incidences of refusal to obey orders on Royal Naval ships, including HMS Vindictive and the cruiser HMS Delhi. Here, poor conditions and war weariness amongst British sailors who had endured four years of war and were now involved in a seemingly unwinable war that lacked public support at home and was plagued by divided objectives and a positive plan to achieve a successful outcome, together with the imminent collapse of the White Russian forces against the Bolsheviks, caused the final withdrawal of the western interventionist forces in early 1920.

The Royal Navy’s losses in the Baltic campaign amounted to the Light cruiser Cassandra, the destroyers Verulam and Vittoria, the submarine L55 and the sloops Gentain and Myrtle, plus the loss of four CMBs. Four E class and three C class submarines at Helsingfors were blown up to avoid capture. The operations led to the deaths of 107 Royal Navy personnel.

In the North Russian campaign on the Dvina and Vaga rivers, British losses amounted to two monitors, M25 and M27, and also the minesweepers Sword Dance and Fandango.

The monitor type of the Great War was a reworking of the coast defence ship, which it was realised could be effectively used for the bombardment of enemy shore positions. This type of ship being of shallow draught meant they were particularly useful on the Russian river systems. They could be built quickly and armed with whatever spare guns that were available, with the largest group of twenty-five or so built mounting either old 6in or 9.2in guns that gave sterling service not only in the Baltic but in the North Sea and the Mediterranean Sea.

Other larger monitors carried 12in and 15in guns and although, for reasons of economy after the war, the majority were scrapped, two of the largest – HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, each of 8,000 tons, both mounting two 15 guns – survived to serve in the Second World War.

The Allied intervention was an expensive operation that achieved little of any consequence and failed in its original purpose to crush the Bolshevik revolution and restore the Tsar, but was instrumental in allowing the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania to achieve independence.