The Roman Empire in 210 after the conquests of Severus. Depicted are Roman territory (purple) and Roman dependencies (light purple).

East and West

Writers sympathetic to Severus claim that the people of Rome celebrated his entrance into the city with garlands, burning torches and incense. The more clear headed Historia Augusta records how the new emperor brought his legions with him, first he made sacrifices at the Capitol, then he moved on to the imperial palace. The thousands of troops had to be billeted across the city in temples, porticoes and shrines, and it appears that they behaved badly, taking what they wanted by force and threatening to lay the city waste.

Matters of state were rapidly dealt with and coins were issued. It must be remembered that for any new emperor coinage acted as a tool of propaganda, and allowed the newcomer to advertise his authority and legitimacy to the man on the street. There was little time to waste in Rome, however, Severus had two rivals for the throne itching to replace him. The first was governor of Britain, Clodius Albinus, whom Severus had already contacted and appeased with a share of the imperial throne. Technically now there were two emperors both issuing their own triumphant coinage, yet both knew the day would come when they would have to meet on some remote battlefield to fight for the throne.

Of more urgent importance was his other rival, Pescennius Niger, the governor of Syria who had been acclaimed emperor by his troops but who had remained in Antioch to gather support and build up his army. Less than thirty days after arriving in the capital, Severus and his armies were hurriedly marching east to intercept Niger’s forces at the earliest opportunity.

Battles between the two forces occurred throughout western Anatolia at Perinthus, Cyzicus, Nicaea and at least one of the passes through the Taurus mountains. By fortifying these passes Niger hoped to protect the northern flank of Syria and his capital at Antioch. Beaten back, he was forced to retreat to that city where he found that support for his cause was beginning to fall away; some of the eastern cities and some of the Roman governors had begun to switch their allegiance. The governor of Arabia, for example, was a native of Perinthus which Niger had attempted to capture. The decisive battle occurred at Issus, where Alexander the Great had defeated a Persian army more than five hundred years earlier. The Severan forces were helped by a thunderstorm which drove rain into the faces of Niger’s legions. Demoralised and retreating, they were ultimately caught in the rear by Severan cavalry which scattered the eastern legions and caught them on the run. The writer Dio claims that Niger’s forces lost 20,000 men in the battle. Niger himself was cornered and beheaded. The rest of 194 was taken up with settling debts, punishing the supporters of Niger and putting his own men in command of the eastern provinces and their legions.

In the spring of 195 Severus launched an attack into northern Mesopotamia, across the Euphrates river in order to punish the Parthian kingdom for its support of Niger. Surviving forces of the defeated Pescennius Niger had fled eastwards and found sanctuary within Parthian territory. Parthia had to be punished; that was the official line. The writer Dio claims that the entire expedition was conceived ‘out of a desire for glory’. Parthia was ‘the East’ and will dominate the narrative of this book. Emperors and generals like Crassus, Trajan and Mark Anthony campaigned in the east to secure glory and stature in the eyes of both Rome and of their own soldiers; Severus was no different. After a bloody civil war he may have wanted to give his troops (both western and defeated eastern) the opportunity to fight side by side, earn some victories and gain some plunder. It was during this period that two new legions, I Parthica and III Parthica, were brought up to strength, probably from the recruits hastily assembled by Niger in the east during his preparations. They would be trained and led by a core of veterans released from the Danubian legions.

During 195 his legions fought at least three major battles against Arab and Adiabeni forces. In response the senate began arrangements back in Rome to construct a triumphal arch for the emperor. While on campaign Severus took the bold step of naming Antoninus, his seven year-old son, ‘Caesar’ – that is, junior co-ruler and heir to the throne. This was a direct challenge to Clodius Albinus in Britain who was now cut out of the succession. Severus decided the time was right to move on his western rival and he began the march back to Rome.

During 196 Clodius Albinus crossed the Channel to Gaul with his own legions (around 40,000 men in total) and began his push to Italy. When he found the Alpine passes blocked he based himself at Lugdunum and began to raise additional forces there. On 19 February 197 the armies of Albinus and Severus met in battle on the outskirts of the city. It was no foregone conclusion, the size of the opposing armies was surprisingly well matched and Severus at one point was thrown off his horse; to avoid being identified and killed he tore off his purple cloak that would identify him as emperor. The arrival of Severan cavalry saved the situation and the battle swung against Albinus. Fleeing inside Lugdunum with some of his troops to escape the enemy, Albinus was forced to commit suicide. In an act of cruel pleasure Severus had his rival’s head cut off and sent to Rome before laying out the naked body and riding his horse over it. As an end to the matter the bodies of Clodius Albinus, his wife and his sons were thrown into the river Rhône.

Septimius Severus was now emperor without rival, with an heir designate and an army that had known nothing but victory. For this restless commander the rest of 197 was taken up with organising his unified empire, rooting out the supporters of Albinus from a number of provinces and marching once more to the east. In a determined attack on the Parthian kingdom, the Roman forces were able to capture and sack its capital, Ctesiphon. The emperor spent five years organising his two new provinces (Osrhoene and Mesopotamia) and touring Judaea and Egypt. He returned to Rome in 202.

The Changes

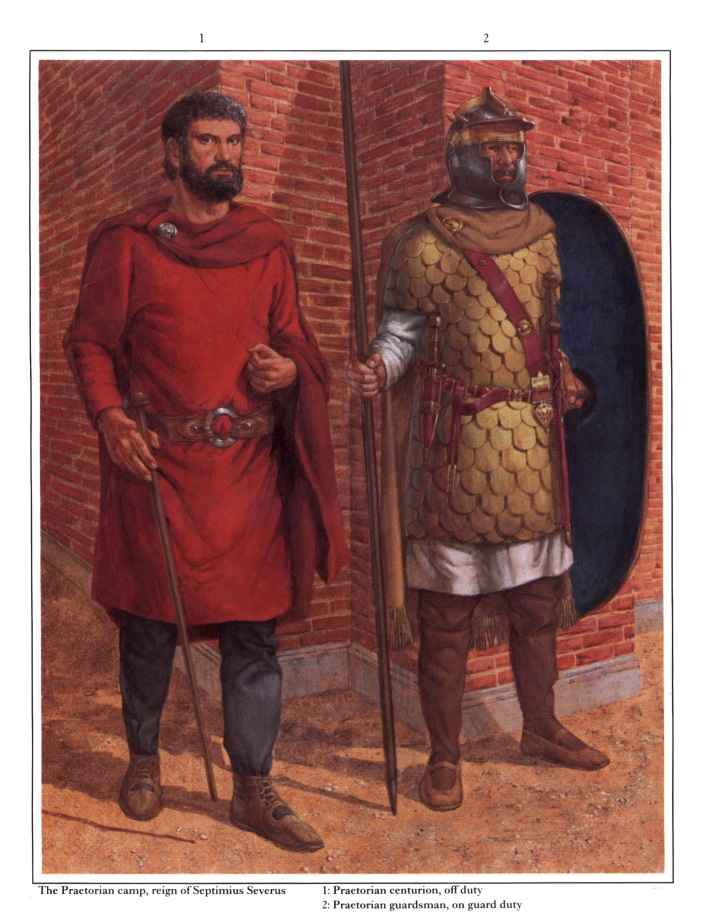

The military changes that would mark Severus’ reign and stand as a legacy throughout the third century began almost immediately. First – the Praetorian Guard. This force of around 8,000 soldiers provided a security force within Rome and provided a vital function, acting as bodyguard to the royal family and as a personal fighting unit on the battlefield. Traditionally open only to men of Italian birth, the Guard was quickly filled by Severus with deserving soldiers who had served in the northern legions. After this point Italians would no longer serve as Praetorians, more than half would come from western legions, the rest were recruited from units in the east. Most of those western legionaries would be Dalmatians and Pannonians. In a stroke Severus had removed a worrying threat and replaced it with a die-hard regiment of loyalist troops who loomed menacingly over Rome in his absence. The Guard still retained its power, however, and its elite membership were still keenly aware of this.

Severus initiated other changes. Three new legions, Legio I, II and III Parthica were established. Recruitment for Legio II Parthica probably began immediately in 193. It was partly raised through conscription of Italian natives, a process called the dilectus, which attracted recruits with the prospect of good pay and the chance of promotion. This was unusual, few Italians marched with the legions anymore. New recruits were more commonly found within the province that a legion garrisoned, and, more often than not, these provinces were out on the frontier. With Legio II Severus smashed tradition and based the new regiment at Albanum barely 34 km from Rome. Up until this point no imperial legion had been allowed a base within Italy in order to prevent it threatening Rome. Troop numbers for Legio I and III Parthica seem to have been raised in the east sometime during the following year. Officers and centurions for these three new legions would need to have some experience and almost certainly came from the Danubian legions that had marched to Rome with their emperor. Not only did this provide a core of military experience at the heart of each new legion, but it also ensured a level of personal loyalty to the emperor from soldiers who had elevated him to that position.

Contemporary writers were greatly concerned by the close proximity of Legio II Parthica to the capital, it represented the abandonment of a long-standing tradition that Romans considered important. At a distance of 34 km (23 Roman miles) it could easily be argued that the legion was positioned to intervene in Rome’s affairs at any time. Writing on military matters in the fourth century AD, Vegetius advises that Roman soldiers should be trained to march 24 Roman miles in five hours, ‘at the full step’, putting Legio II within five hours march of the capital. Was this an act of intimidation or one of defence? Opinion is divided.

Of more personal interest to the soldiers themselves, Severus gave his troops the right to marry. They had previously been able to have relationships with local women, unrecognized in law, and some maintained these partnerships through many years and several postings. Children were born within these relationships, but all were illegitimate. Marriage provided the wife with the legal right to her late husband’s estate and it legitimised his offspring. Such a move would have been good for morale and bolstered the opinion of Severus amongst his troops.

The grant to marry while in service was not the only popular appeal to the soldiery. For the first time since emperor Domitian (AD 81–96) Severus raised the annual pay of the legionary from 300 to 450 denarii. Likewise the auxiliary soldier saw his pay climb from 100 to 150 denarii. Legionary cavalry pay rose from 400 to 600 denarii, auxiliary cavalry pay rose from around 200 to around 300 denarii if part of a cohort, or from 333 to 500 denarii if part of a cavalry wing. Severus’ son Caracalla later followed suit after his father’s death, increasing pay so that it was double the value it had been during Commodus’ reign. Any increase was overdue; inflation had left the soldiers’ pay standing and increased the chance of the troops rallying to any leader who promised a donative (a one-off gift of money) should they fight for him in any civil war. Yet these large increases in pay cost the imperial treasury dearly, resulting in a debasement of the coinage.

Although these reforms resembled gifts bestowed on the legions by a grateful emperor, they did not destabilise the relationship between army and state. Far more damage was done by the favour now shown to frontier troops. Recruited from frontier provinces to maintain the manpower of legions stationed there, new recruits were often effective fighters. However, they lacked the crucial understanding any Italian would have, that a soldier of Rome owes absolute loyalty to the remote SPQR, the ‘Senate and the People of Rome’ and of course, to the man at the head of it all, the emperor. Legions manned by frontier recruits had a different loyalty, to that general who would give them donatives or chances for war and plunder.

At the command level, loyalties were also being tested to breaking point. Many centurions serving within the legions had been promoted from the ranks of the Praetorian Guard in Rome. Most would be Italians, with a strong sense of allegiance to the emperor, to Rome and to its institutions. Now that provincials from Britain, the Rhine and Danube were dominating the barrack blocks of the Guard, promotion to the centurianate of a legion no longer carried with it that traditional allegiance.

Command of the legion was the responsibility of a senator. As a legionary legate, this would mark another rung on the senator’s career ladder. Of course the senate embodied Rome, Roman values and Roman thinking – yet from the reign of Severus the number of senators receiving command positions began to drop until, by the reign of emperor Gallienus in 261, they were forbidden by statute to serve as legates at all. Instead the position was gradually opened up to the equestrians, a large ambitious class of wealthy families who were normally excluded from the privileges and responsibilities of government.

In all, Septimius Severus had aggrandised the legions, he was practising his own advice: ‘give money to the soldiers, and scorn all other men.’ Empowering the soldiers, in effect buying their loyalty with cash, promises and privileges, was crucial for the winner in a civil war, for if Severus could unseat an usurper so another chancer might just as easily march on Rome and do the same … unless the rules were changed. Severus was changing the rules, closing the door to potential rivals. That was probably his intent at any rate but in doing this he was handing over the keys of the empire to the miles, the common soldier.

Once Severus and his close kin were out of the picture the legions would not owe the new emperor any loyalties whatsoever. The seeds of disaster were sown.