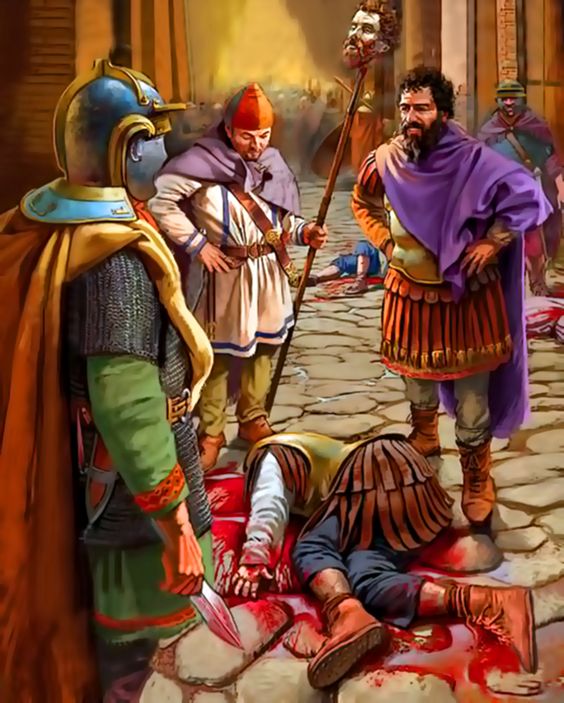

Septimius Severus and his men contemplating the corpse of his rival for the throne – after the first victory in the Battle of Lugdunum.

‘“You have trained under actual combat conditions in your continuous skirmishes with the barbarians, and you are accustomed to endure all kinds of labour. Ignoring heat and cold, you cross frozen rivers on the ice; you do not drink water from wells, but water you have dug yourself. You have also trained by fighting with animals, and, all in all, you have won so distinguished a reputation for bravery that no one could stand against you. Toil is the true test of the soldier, not easy living, and those luxury-loving sots would not face your battle cry, much less your battle line…” After Severus had finished speaking, the soldiers shouted his praises, calling him Augustus … and displaying the utmost zeal and enthusiasm for him.’

Herodian II.10

While chill February winds whipped around the towers and wall-walks of the legionary fortress, an old man lay dying in the luxuriously furnished house that belonged to its commander. He was in his sixties, yet he was still strong-minded, ebullient and able to talk with both his advisors and his two attentive sons. The old man was Septimius Severus, emperor of Rome. He was far from that city, living with his vast staff of advisors and courtiers, at the centre of the fortress in Eboracum, northern Britannia. Here 5,000 soldiers lived and worked, and were currently resting after fierce fighting in far flung Caledonia. But Severus liked to be surrounded by soldiers, even on his death-bed he would have found the idea comforting. It was the common men of the legions that had elevated him to the throne, followed him into battle and criss-crossed the empire to fight for his glory and his favour.

Even though these soldiers would die to preserve their emperor’s life, there were doubts about others who stood in his bed-chamber. Dio Cassius, a senator and advisor on the campaign, remembered hearing rumours that Antoninus, the emperor’s eldest son, had tried to hasten his father’s death. Another historian, Herodian, stated bluntly that the treacherous Antoninus had actually bribed the court physicians to bring this about.

With death clutching at him, Septimius Severus had a final meeting with his squabbling sons. Both had been proclaimed as heirs and joint co-emperors, but both were intensely fearful that when the time came the other would seize the throne for himself. Dio relates to us ‘without embellishment’ the emperor’s last words of advice to his sons. The secret of his success in war, justice, politics and administration was summarized simply with the advice: ‘agree with each other, give money to the soldiers, and scorn all other men.’

There was little chance of his sons getting on, as events later that year would show, but his last two recommendations were ruthlessly implemented by Antoninus and by successive emperors throughout the third century. Simply put, Severus was telling his sons to lavish money and attention on the legions in order to secure their loyalty. He had done this himself in order to fight off rivals in a civil war. Severus could not call on dynastic loyalties, he could only call on the military barrack-room loyalties of soldiers who had served under him as governor. But those loyalties were always fickle, and maintained by gold and battlefield plunder. To retain the throne he had learnt to cultivate his relationship with the legions in a way that no emperor had done before. He dearly hoped that his successors would do as well in the dark days that were to come.

On 4 February 211, Lucius Septimius Severus, the twenty-first emperor of Rome died. The dynasty he established would last another twenty years before chaos and turmoil would reign…

Legions on the Danube

The source of emperor Severus’ power came from the legions, but more specifically it came from the legions stationed on the Danube frontier. This set of provinces (Raetia, Noricum, Pannonia and Moesia) bound both the eastern and western halves of the empire together. They formed, along with their legions, a vital bulwark against which the belligerent tribes of Dacia and Germany crashed. Its legions were motivated and battle-hardened, and crucially for the fate of any would-be emperor, there were a lot of them.

Forty years of warfare on this Roman border had resulted in a massive build-up of military might. Further west the river Rhine acted as another frontier barrier and legions were also encamped there, ready to repulse frequent raids by German tribes. As pressure from northern tribes like the Quadi, Marcomanni, Naristi and Iazyges intensified, so did the Roman build-up. The Danubian army soon became the largest in the empire. During the on-going civil wars that would erupt throughout the third century the candidates that competed so violently for the throne more often than not were promoted by the soldiers garrisoned on the Danube. Maximinus I, for example, was an ex-legionary, risen through the ranks of a Danubian unit and he gained the support of his fellow-soldiers. From humble origins he become emperor of Rome. It was obvious that these legions held real power; at this crucial cross-roads in ancient history the fate of the empire rested on their shoulders.

It had not always been so. Emperors prior to 162 had only to deal with the German threat across the Rhine, and did so with a military force equal to the task. The river Danube flowing east formed a natural frontier that had been lightly protected, considering its length, and this had been up till now adequate protection. Indeed a new province, Dacia, had been carved out of barbarian territory across the Danube by emperor Trajan. In 162, however, and for a number of years afterwards, Germanic tribes invaded Roman territories, including the Danubian province of Raetia. Marcus Aurelius had two new legions recruited around 165 as an emergency measure, these would become Legio II Italica and Legio III Italica, garrisoned in Noricum and Raetia respectively.

The attacks worsened. In 166 and 167 tribes called the Langobardi, Ubii and Lacringi invaded Pannonia, whilst the Vandals and Iazyges attacked Dacia, killing the governor there. Marcus took his new legions northwards in 168 and so began a protracted campaign against the new barbarian threat. During these wars the barbarian armies crossed the Danube and ravaged parts of the empire, the Costoboci reaching as far south as Eleusis in Greece. Balomar, king of the fierce and well-organised Marcomanni even defeated 20,000 legionaries at Carnuntum in 170 before marching south into Italy to besiege the city of Aquileia. The Roman counter-offensive included both diplomacy and force, and by 180 most of the warring tribes had either been won over or subjugated.

In 180 Marcus Aurelius died while on campaign against the Quadi. His son Commodus had no interest in fighting the war and he left his generals, including Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus, to continue it in his absence.

A decade of intense warfare on the doorstep of Italy had shown how vulnerable the empire was to a concerted attack. Yet these Marcomannic Wars were to be but a foretaste of the future barbarian migrations that would end with the collapse of the western half of the empire three centuries later. The threat to Rome was soberly understood, however, resulting, by the end of the Marcomannic Wars, in half of the empire’s military force being stationed behind the Rhine and the Danube. This constituted sixteen out of the empire-wide total of thirty legions.

It was in the year of Marcus Aurelius’ death that a thirty-five-year-old senator from North Africa, Lucius Septimius Severus, gained his first military command. Septimius Severus took up the office of legate, the commanding officer in charge of Legio IV Scythica. Severus would later fight off opponents to become emperor himself, but while in Syria he made contacts, gained valuable experience and may have met his future wife, Julia Domna.

The IV Scythica was one of three legions in Syria, which was the crucial eastern province which held at bay the might of the belligerent Parthian Empire. Governing this wealthy, eastern province was Helvius Pertinax who will have worked closely with his three legionary commanders, including of course Septimius Severus. Legionaries of the IV Scythica will have visited forts and garrison towns along the eastern frontier, including the city of Dura Europus. It is likely that Severus, too, inspected these garrisons, to check on their preparedness should the Parthians choose to over-run the frontier during his time in office.

As commander of the most prestigious of the Syrian legions, Severus may even have been acting governor for a short time. Pertinax, Severus and hundreds of men like them across the empire were of the senatorial class and not soldiers by birth. They competed for better and more prestigious public offices, both administrative and military, in their pursuit of status, wealth and respect. Pertinax, when he was around Severus’ age, had secured for himself command of the Roman fleet on the Rhine, followed soon after by promotion to chief financial officer (procurator) of the Dacian province. The much younger Septimius Severus was similarly eager to climb the ‘ladder of honours’ in search of fame and fortune.

Both Pertinax and Severus later received the governorship of provinces in the western half of the empire, the former of Britannia, the latter of Lugdunensis (southern France). During Septimius’ tenure as governor his wife died and, in 187, he made contact with the high priest of Emesa in Syria to ask for the hand of one of his two daughters in marriage. This was Julia Domna, who sailed to Lugdunensis in order to marry Septimius Severus in the summer. By 192 Pertinax had risen to the position of Prefect of the City and then to consul of Rome in partnership with the young emperor Commodus. Severus, meanwhile, had been made governor of Upper Pannonia. Such an appointment was unexpected. This province, which lay along the vulnerable Danubian frontier, was home to three tough battle-tested legions and no large troop concentration lay nearer to Italy. The command of such a crucial concentration of legions had rarely been given to men who had not earned that position first through the successful governance of several other key provinces. Almost simultaneously Severus’ brother, Septimius Geta, was appointed governor of Lower Moesia, another key Danubian province with two legions of its own. Responsible for the appointment of Septimius Severus was the new commander of the Praetorian Guard, Aemilius Laetus. Perhaps it was no surprise that he hailed from North Africa too, one of a growing number of North African Romans of influence and power within Commodus’ government.

North Africa was not some backwater of empire at this point, it was a thriving region that provided a large proportion of Rome’s grain. Over three centuries earlier the powerful city of Carthage had dominated North Africa and fought three wars with Rome for control of the western Mediterranean. Carthage had been defeated and not just defeated but dismantled and destroyed, its cropland salted and cursed. Over the past three centuries however, newly established Roman provinces in North Africa grew and steadily developed. By the time of Marcus Aurelius, educated and wealthy Roman Africans were reaching great heights, whether they were descended from Italian settlers or old Carthaginian notables.

It may be that Laetus was indeed motivated by native loyalty, or perhaps he simply chose the best man for the job. Whatever his motivations, his choice had extraordinary repercussions on the fate of the empire and on the legions that protected it.

Severus Takes Rome

Commodus, son and heir of Marcus Aurelius who had fought so hard to prevent the northern frontiers from being overrun in the Marcomannic Wars, was a vain, cruel, paranoid fantasist about which none of the ancient writers had anything good to say. There had been several failed plots against his life, it was only a matter of time before one of them would succeed. The Prefect of the Guard, Laetus, and the emperor’s chamberlain, Eclectus, were instrumental in the assassination of Commodus on New Year’s Eve 192. When the poison he was tricked into consuming merely made him ill, the athlete Narcissus was sent in to finish the job by strangulation. One ancient source implicates another influential individual in the murder: Helvius Pertinax. As consul of Rome it was Pertinax who now stood forward to claim the imperial throne. He made a speech within the walls of the Praetorian camp which was the home of the imperial bodyguard. Offering each soldier 12,000 sesterces and announcing that Commodus had died suddenly of natural causes, he asked for the loyalty of the Praetorian Guard. There was hesitation and a little resistance but the troops eventually came around to Pertinax and acclaimed him emperor. Without their support he stood no chance since the Praetorians had gained a reputation in years gone by as masters of the throne. Several emperors owed their good fortunes (and lives) to the whim of these imperial bodyguards. Past emperors Domitian, Otho and Claudius all owed their places on the throne to the actions of the Guard, while the emperors Galba and Vitellius died at the hands of disgruntled Praetorians. When emperors passed on the empire to a nominated successor the Guard had been happy to transfer its loyalty to the new incumbent, whether a blood relative or an adopted heir. In times of dynastic uncertainty, however, the Praetorians were keen to impose their will, or at least receive some kind of payment for their loyalty.

The elevation of Pertinax to the imperial throne proved to be one of those times of ‘dynastic uncertainty’, and although the Guard had been bought off, the loyalty that it purchased would not last for long. The sixty-six year-old emperor tried to change too much, too quickly and crucially attempted to curb some of the excesses of the Praetorian Guard. Resentment against Pertinax grew quickly with the inevitable result that the Guard turned against him. On 28 March three hundred soldiers burst into the imperial palace on the Palatine Hill to challenge the emperor. Despite his attempts to appease them, the Praetorians killed him with their swords. His reign had lasted only eighty-seven days.

The uncertainty created by Commodus remained, there had to be an emperor, but whoever stepped forward had first to deal with the fickle Praetorians. The soldiers returned to the Praetorian Camp fearful of the public reaction, no obvious candidate existed for them to elevate to the purple … and so heralds on the walls of the camp announced the public sale of the throne and not one, but two buyers came forward! Of the two, Flavius Sulpicianus (Pertinax’s father-in-law) and Didius Julianus (a wealthy and respected senator), it was the latter who won the auction. However, the Praetorian’s choice did not prove popular with either the people, the senate or, in the end, the Praetorians themselves. They soon tired of Julianus who did not appear to have the means to honour his lavish promises.

Other candidates for the throne had declared themselves upon hearing the news of the death of Pertinax. Yet these candidates had nothing to do with the sordid auction within the Praetorian Camp, or with attempts to flatter or bribe the imperial bodyguard. These three claimants to the throne were governors in provinces that were home to powerful military contingents and all had a good chance of seizing power. The governor of Syria, Pescennius Niger, was proclaimed emperor in mid-April by the four legions under his command. Later that month Clodius Albinus, the governor of Britannia, also claimed the throne. He had three legions to back up his claim. However, a candidate with some serious military backing had already emerged. Septimius Severus was governor of Upper Pannonia and proclaimed emperor by his troops on 9 April, barely two weeks after the murder of Pertinax. Not only did Severus enjoy the loyalty of the three legions under his provincial command, he had also managed to secure the support of all the legions on both Rhine and Danube frontiers. This amounted to a combined force of sixteen legions, should he dare to mobilize them all.

Having the strongest hand in the game and being the closest to Rome, Severus marched on the capital. Didius Julianus, with the nervous support of the senate, made attempts to defend the city from attack, but with little real success. As Severus and his legions approached the city the senate hastily passed a motion that sentenced Didius Julianus to death and it also bestowed divine honours on the dead emperor Pertinax. Its membership was well aware of the friendship between the murdered emperor and the approaching general. Julianus was summarily executed by an officer; he had ruled Rome for only sixty-six days.

Severus and his army entered Rome without opposition. He was now emperor of Rome and he took the name of Pertinax as part of his own imperial title. What did the Praetorian Guard do about this turn of events? By the time Severus crossed the city boundaries, the Guard had already been disbanded. He knew full well that although the imperial bodyguard might be overawed by the number of troops he had brought with him to secure his claim, months or years down the line they may have a Fate in store for him not too dissimilar to the one they had meted out to Pertinax. Of course Septimius Severus had to be seen to punish the murderers of Pertinax and that was quickly achieved – the men involved were surrendered to him.

To deal with the Guard, he had to be clever and avoid an armed confrontation. Severus asked the Praetorians to pay homage to him in ceremonial dress (that is in off-duty attire, without swords, helmets or armour). When they paraded outside Rome in front of him, Severus then ordered his loyal troops to strip the Praetorians of their military belts, their daggers, uniforms and military insignia. All of the assembled Praetorians were formally discharged and instructed never to set foot in Rome again. The cavalrymen had to let their horses loose, although one horse followed its rider in a stubborn refusal to leave him. The Praetorian was forced to kill the horse and then himself. Thus the Guard was disbanded without a fight.