The early years of US naval aviation were marked by rapid changes in technology and extremely limited budgets in the post-First World War era. That meant the US Navy bought small lots of aircraft from numerous manufacturers, always seeking the best in performance while it transitioned from biplane to monoplane, and tested tactics and doctrine for its new aircraft and carriers. Aircraft did not last long in frontline service as they rapidly were superseded by newer, more advanced designs.

The Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur, made their first powered flight on 17 December 1903, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. They did not stand on their laurels and continued to refine the design of their aircraft to improve its performance. The US Navy was not that interested, but did have the foresight to send military observers to aerial demonstrations within the United States and overseas to monitor the progress of aviation technology.

The continuing advancement in aircraft designs following the Wright Brothers’ demonstration in 1903 was becoming harder for the US Navy’s senior leadership to ignore as the years went on. In response, the Secretary of the US Navy (a civilian-appointed position) placed Captain Washington I. Chambers in charge of all aviation matters.

To show off the potential offered by aircraft, Captain Chambers had a short temporary wooden platform built on the bow of the US Navy cruiser USS Birmingham (CL-2). On 14 November 1910, civilian pilot Eugene B. Ely successfully flew off the ship, in a civilian wheeled airplane built by the Curtiss Aeroplane Company, founded by Glen H. Curtiss. Approximately two weeks later, Curtiss offered to train a single US Navy officer how to fly, and was taken up on his offer.

In the meantime, Captain Chambers arranged to have a longer temporary wooden platform constructed on the stern of the US Navy cruiser USS Pennsylvania (ACR-4). It was intended to provide the room needed for Eugene B. Ely to land and then take off from the ship (then moored in San Francisco Bay) a feat that he accomplished on 18 January 1911. It was also the first use of arresting gear, to slow down and stop the aircraft after landing.

Glen H. Curtiss made the first successful floatplane flight, taking off from San Diego Bay on 26 January 1911, in an aircraft he designed and his firm built. The following month, Captain Chambers arranged to have Curtiss taxi his floatplane out to the USS Pennsylvania, now moored in San Diego Bay. Once adjacent to the ship it was hoisted aboard by a crane and then lowered back into the water. This test was conceived by Chambers and Curtiss to prove the ability of floatplanes to operate from US Navy ships.

Development Continues

The publicity tests put together by Chambers and Curtiss had the desired effect on the US Navy’s senior leadership, and on 4 March 1911 the first funds for naval aviation were appropriated. It was at this point in time the Wright Brothers offered to train a single US Navy officer how to fly, if, in exchange, the service would purchase one of their aircraft for the sum of $5,000.

On 8 May 1911, Chambers prepared the necessary paperwork for the US Navy to acquire three aircraft. Of the three planes, the first two to enter service were Curtiss-designed and built aircraft. The first of these two Curtiss airplanes to arrive was nicknamed the A-1. The initial flight of the A-1, in its wheeled configuration, took place on 1 July 1911. The ability of the aircraft to land and take-off from the water as a floatplane was demonstrated ten days later. A few days later the second Curtiss aircraft ordered was delivered to the US Navy and was designated the A-2.

The US Navy also took into service the first of a small number of Wright Brothers-designed and built aircraft in July 1911. The first plane to arrive was designated the B-1. It, and the other airplanes acquired from the Wright Company (formed in 1909 by the Wright Brothers) were eventually configured as training floatplanes.

Pre-First World War Floatplanes and Flying Boats

The US Navy took into service the first of five Curtiss flying boats in 1912, which the company labelled the Model F. They were initially numbered in sequence from C-1 through C-5 by the US Navy. They received a two-letter prefix code of ‘AB’ in March 1914. The ‘A’ stood for heavier-than-air-craft and the ‘B’ for flying boat. AB-2 was the first US Navy aircraft launched by catapult from a ship while underway, an event that took place on 5 November 1915.

In January 1916, the Curtiss Aeroplane Company became the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company. By 1917, Curtiss Model F flying boats had become the US Navy’s standard training aircraft, with 150 built between 1916 and 1917.

Unlike floatplanes that depend on under-fuselage pontoons for buoyancy on the water, flying boats depend on their boat-shaped fuselages for buoyancy. Flying boats often employed outrigger pontoons on the end of their wings for added stability in the water. At the time, flying boats were known as hydro-aeroplanes. Floatplanes and flying boats both fall under the umbrella term of seaplanes.

In October 1913, the US Navy’s second Curtiss-built aircraft, designated the A-2, had its original float pontoon replaced by a flying boat fuselage containing a three-wheeled landing gear. This provided the aircraft the ability to land and takeoff from airfields, or the water. With this added feature, the airplane became an amphibian flying boat. Floatplanes can also be fitted with wheels to become amphibians.

Naval Aviation in Action

The largest contribution made by naval aviation during the First World War proved to be the establishment of a number of shore bases along the French, Irish, and Italian coasts. From these bases, US Navy pilots and air crews primarily flew anti-submarine patrols in flying boats, such as the Curtiss-designed twin engine H-16. The H-16 was eventually superseded in production by the F-5L, a US-modified version of a British-designed flying boat.

When the First World War came to an end on 11 November 1918, naval aviation had 2,107 aircraft, with many of them being floatplanes of foreign design. By 1919, the bulk of the naval aviation assets acquired during the First World War were gone; scrapped or placed into storage. The thousands of men who had manned and serviced these craft were demobilized. As the First World War was also known as ‘The War to End All Wars’, few politicians or their civilian constituents foresaw any need for retaining the men and their equipment.

A Vision is formulated

Looking forward it was clear to the senior leadership of the US Navy that the future of naval aviation lay in having a suitable array of aircraft to perform a variety of tasks. As a result, on 13 March 1919, the Chief of Naval Operations issued a preliminary program for post-First World War development. That program called for a number of specialized aircraft for service with the fleet on its battleships and cruisers, as well as the newly-envisioned inventory of aircraft carriers, typically shortened to just carrier.

In addition to those aircraft planned for use with the fleet when at sea, the US Navy also saw a requirement for land-based patrol planes that could protect convoys from enemy submarine attacks. A hitch in that requirement occurred in 1931 when the US Navy and US Army Air Corps agreed that only the latter could operate shore-based multi-engine aircraft. This restricted the US Navy to employing shore-based seaplanes and ship-based aircraft.

Catapult-Launched Aircraft

Beginning in 1926, catapult-launched single-engine floatplanes, officially classified as scouting and observation planes, began serving on US Navy battleships and cruisers. Their main job eventually became spotting for naval gunfire, the scouting role being taken over by wheeled carrier aircraft. They also had a backup role as utility aircraft and occasionally performed in the search and rescue role. All of the catapult-launched single-engine floatplanes could be fitted with wheels in place of their large under-fuselage float if required.

The first generation of scouting and observation floatplanes launched by catapult from US Navy battleships and cruisers all came from Chance Vought, with the initial production model designated the O2U-1 Corsair. Progressively improved models were labelled the O2U-2 through O2U-4 Corsair. By 1930, another variant was referred to as the O3U Corsair, evolving from the O3U-1 through O3U-4 Corsair.

When the O3U Corsair series was assigned to carriers in the wheeled observation-only configuration, they were relabelled SU-1 through SU-4. The later production models of the planes lasted in service up to early 1942. Rather than US Navy squadrons, the Corsair observation series planes assigned to carriers where flown by Marine pilots, the first to fly from US Navy carriers. In total, 580 units of the Corsair series were built by Vought.

The letter ‘U’ in the designation code for the various versions of the Corsair observation planes stood for Chance-Vought. Over the decades to follow, the firm would pass through numerous iterations of corporate ownership, as did many aircraft builders. To simplify, the name Vought will be retained hereafter to identify all aircraft from the various corporate entities that owned the firm.

The eventual replacement for the early generation Vought catapult-launched single-engine floatplanes was the Curtiss SOC Seagull, of which 323 were acquired in various models. Like the floatplanes that came before, it was a biplane. It entered into US Navy service in 1935 and was eventually superseded in service by the Vought OS2U Kingfisher, beginning in August 1940. Unlike all the catapult-launched single-engine floatplanes that came before it, the Kingfisher was a monoplane. The US Navy took in 1,159 units of the Kingfisher series.

Patrol Flying Boats

To replace its aging inventory of First World War-era patrol flying boats, the Naval Aircraft Factory (NAF) decided to upgrade the design of the F5L patrol flying boat. The resulting aircraft appeared in US Navy service in 1924 as the PN-7. It was followed into service by small numbers of successively improved versions, designated the PN-8 through PN-12, with the latter being the definitive design. The letter ‘P’ stood for patrol and the letter ‘N’ for the first letter in the builder’s name, in this case the government-owned NAF.

The US Navy eventually decided they wanted an improved version of the PN-12. As the NAF could not build as many improved units of the PN-12 as the US Navy desired, it contracted with various civilian firms in 1929 to build an upgraded version. The first to enter service was the Douglas PD-1. It was later joined in service by the Martin PM-1, the Keystone PK-1, and the Hall Aluminum Company’s PH-1. All were basically the same aircraft with minor differences between the various companies’ products.

In the late 1920s, the US Navy was looking for the next generation of flying boats. First acquired was the twin-engine Martin P3M, which was a Consolidated Aircraft-designed aircraft for which Martin had won the production contract. However, only nine units of the Martin P3M series were built. The Martin P3M was quickly superseded by the US Navy’s adoption of the superior Consolidated P2Y flying boat ordered in 1931. There were three models of the P2Y. Both the Martin P3M and the Consolidated P2Y were pulled from frontline US Navy service in late 1941.

The frontline replacement for the Consolidated P2Y and the Martin P3M was the twin-engine Consolidated PBY Catalina, which entered into US Navy service in 1936. The letter ‘B’ in the designation prefix code stood for ‘bomber’ and the letter ‘Y’ for Consolidated. The number of Catalina series aircraft completed by 1945 ranges from a low of 2,300 to a high of 3,100 units, depending on the reference sources quoted. Many of the Catalina series aircraft would serve into the early postwar years.

Martin delivered to the US Navy a twin-engine amphibian seaplane beginning in 1940, designated the PBM-1 Mariner. It was built in numerous models, up through the PBM-5, which served during the Second World War up through the early postwar years, including the Korean War. There were at least 1,000 units of the Mariner constructed by 1945.

1920 Fighters

During the First World War, the US Navy had borrowed some foreign-designed and built fighters from the US Army, but never employed them in combat. Immediately after the conflict, the US Navy continued to acquire US Army aircraft, one of these being the Vought VE-7 two-seat trainer. The US Navy thought so highly of the aircraft that they brought a single seat variant into service in 1920 as a fighter, designated the VE-7S.

The VE-7S was the first aircraft launched from the flight deck of the then still experimental USS Langley (CV-1) on 17 October 1922. In 1925, the first US Navy squadron assigned to the USS Langley (now in fleet service) was equipped with eighteen of the VE-7S. The fighter remained in US Navy use until 1927. For a single year in 1923, the US Navy referred to its fighters as pursuit planes, which is how the US Army Air Corps identified their fighter planes.

Carrier-Capable Fighters

The first purpose-built fighter actually ordered by the US Navy and intended for carrier use was the TS-1 that appeared in service in 1922. It was designed by a civilian working for the Bureau of Aeronautics, which had been established the year before. The new bureau had brought almost all the once divergent responsibilities for US Navy aircraft under one roof. Curtiss won the contract to build thirty-four units of the TS-1 fighter, with the government-owned NAF assigned to build five of them. The aircraft lasted in US Navy service until 1930.

Boeing soon jumped into the competition for supplying the US Navy with the fighter planes it needed. In 1925, the US Navy took into service ten of the land-based Boeing FB-1 fighters. It was followed into service by approximately thirty FB-2 through FB-5 fighters, the latter version entering service in 1927. The Boeing FB-2, FB-3, and FB-5 had been designed for carrier use, while the FB-4 was a seaplane fighter, only one being built. The letter ‘F’ in the designation codes stood for fighter and the letter ‘B’ for Boeing.

Boeing also began building for the US Navy another series of fighters, with a different type of engine. These aircraft were all intended for carrier use and labelled F4B-1 through F4B-4, with the first delivery of the F4B-1 in 1929 and the last, the F4B-4 in 1932. The latter was the last Boeing fighter built for the US Navy before the Second World War. In total, 186 units of the Boeing F4B-1 through F4B-4 were built, and they would continue to fly with the US Navy until 1939.

Curtiss also wanted in on the US Navy contracts for fighters and achieved success in 1925 when he made his first delivery of an aircraft, designated the F6C-1 Hawk, of which the US Navy ordered nine units for carrier use. Of the nine F6C-1 Hawks ordered, four were eventually completed as the F6C-2 Hawk. Two years later he began delivery of thirty-five units of a carrier fighter referred to as the F6C-3. The aircraft could be configured as a seaplane if the need arose by the replacement of its wheels with floats. Following the F6C-3 into service were thirty-one units designated the F6C-4. The letter ‘C’ in the aircraft designation stood for Curtiss.

1930 Fighters

In 1929, the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company merged with the Wright Aeronautical Corporation to become the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, hereafter referred to as Curtiss-Wright for the sake of brevity. The following year, Curtiss-Wright was awarded a contract by the US Navy for five examples of a multi-role carrier-based twin-seat fighter-bomber/observation plane designated the F8C-1 Falcon to be employed by the Marine Corps.

Service use quickly demonstrated the Falcon was much slower than existing single-seat fighters and it was pulled from frontline US Navy carrier use in 1931. The US Marine Corps continued to employ the aircraft as a land-based observation plane. Reflecting its new job, the F8C-1 was re-designated the OC-1, with the letter ‘O’ standing for observation plane. Twenty-one units of an improved model built by Curtiss-Wright were labelled the F8C-3 Falcon and re-designated the OC-2 Falcon.

A follow-on version, the F8C-4, was nicknamed the Helldiver instead of the Falcon, and twenty-five were delivered to the US Navy beginning in 1930. They were quickly turned over to naval reserve units and the US Marine Corps the following year. It was then designated as the O2C Helldiver. A follow-on F8C-5 variant, primarily employed by the US Marine Corps, was labelled as the O2C-1 Helldiver, and remained in service until 1936. The US Marine Corps saw the O2C and O2C-1 as having a secondary role as dive-bombers.

In 1932, Curtiss-Wright began delivery of twenty-eight units of another carrier fighter-bomber, designated the F11C-2 Goshawk, which was re-designated as the BFC-2 Goshawk in early 1934. The re-designation better reflected the aircraft’s dual-purpose role as both a fighter and as a dive bomber. The letter ‘B’ in the new designation stood for bomber and the ‘F’ for fighter. The original Goshawk was followed into service in 1934 by another twenty-seven units of an improved version, designated BF2C-1 Goshawk. The two-letter prefix code ‘BF’ was a short-lived US Navy designation.

The Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation entered the contest for supplying fighters for the US Navy at the request of the Bureau of Aeronautics in 1931. The US Navy liked what they saw and took into service the first of twenty-seven units of a two-man aircraft in 1933, labelled the FF-1. The second ‘F’ in the designation code stood for Grumman. The FF-1 lasted in US Navy frontline service until approximately 1935. In a secondary role as a trainer the aircraft survived in use until 1942. In its two-seat scout configuration it was designated SF-1 and thirty-three were purchased by the US Navy.

Unlike the fighter designs of its competitors, the FF-1 had an enclosed cockpit and retractable undercarriage, which led to an increase in maximum speed as the airplane’s fuselage was more streamlined. These design features led to the Grumman aircraft out-performing the fighter designs from both Curtiss and Boeing.

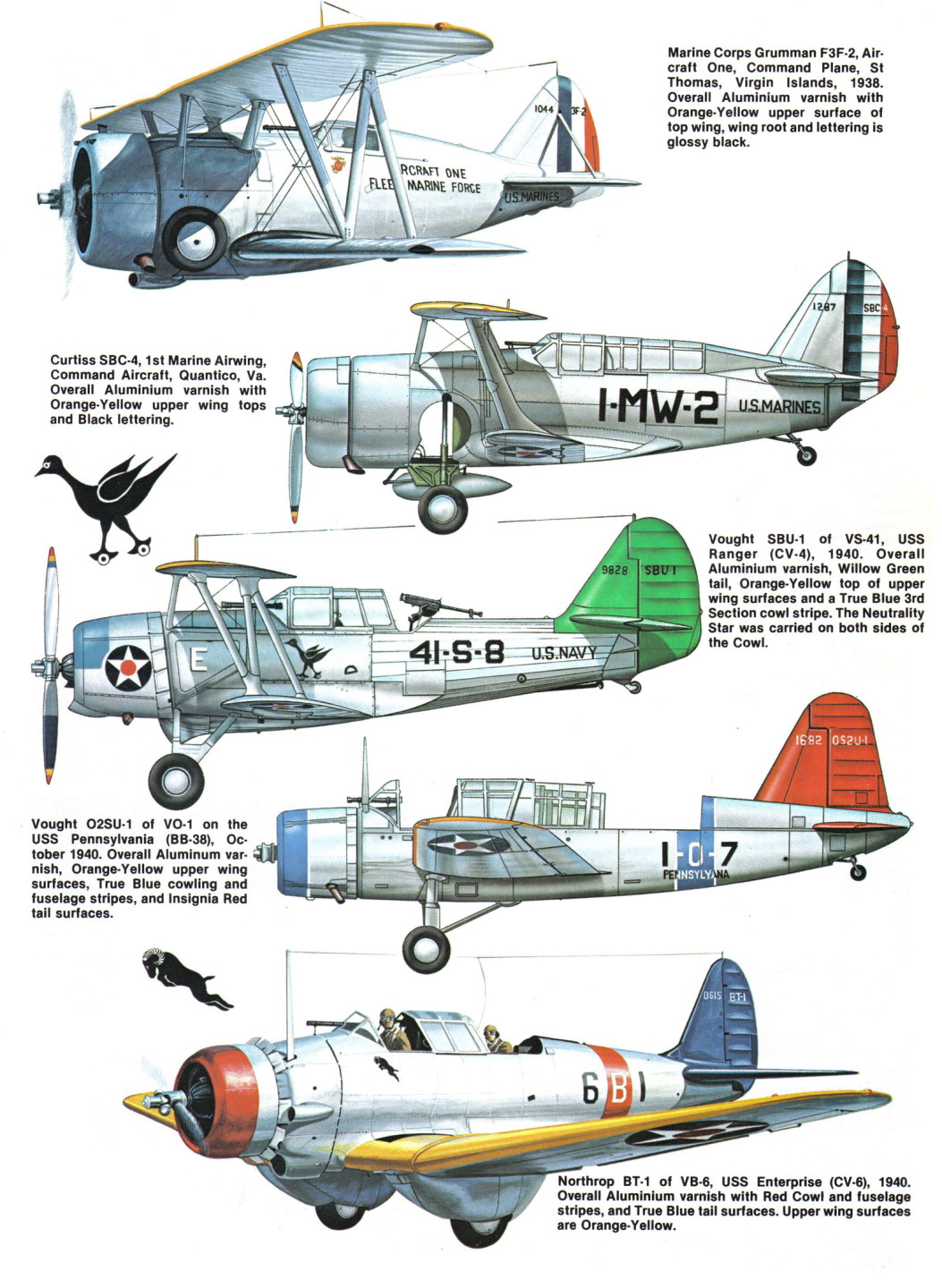

The FF-1 from Grumman was superseded in US Navy service in 1935 by the delivery of fifty-four units of an improved one-man version of the aircraft, designated the F2F-1. It remained in use on carriers until 1940. The F2F was then overtaken on the production line by the F3F-1 in 1936, and then through the F3F-3. The latter entered service in 1938, and remained in the inventory until 1940. A total of 162 units of the F3F series were built.

On the Eve of War Fighters

In late 1935, the US Navy opened a competition for the next generation of carrier fighters. Three companies vied for the contract. In the end, a fighter, designated the F2A-1, was chosen. The letter ‘A’ in the designation code stood for the Brewster Aeronautical Corporation.

The F2A-1 was the first monoplane fighter in US Navy service; all those that had come before were biplanes. The US Navy ordered fifty-four of the aircraft in 1938. However when completed, forty-three went to the Finnish Government and only eleven were taken into US Navy service at the end of 1939.

At the same time as the US Navy ordered the F2A-1 into production, it asked Grumman, one of the competing firms for the contract, to keep working on improving their own aircraft design, which was a biplane and greatly impressed the US Navy. This was done as a backup plan in case the F2A-1 did not live up to the US Navy’s expectations.

The delivery of forty-two units of an improved version of the F2A-1 to the US Navy, referred to as the F2A-2, occurred in late 1940. Unfortunately, combat reports from the Royal Air Force (RAF) indicated that the F2A-2 was badly outclassed by German front-line fighters. It was the RAF that officially named the F2A-2 the ‘Buffalo’, a name then adopted by the US Navy for the entire series. A small number of Buffalos would go on to serve with the Royal Navy (RN).

A request for more armor protection on the F2A-2 by the US Navy and foreign users of the plane resulted in the production of the next version, designated the F2A-3. It was delivered to the US Navy a few months before the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. However, the plane’s added weight made it difficult to fly. Service use of the heavier F2A-3 demonstrated that its landing gear system was not tough enough to withstand the repeated shock of landings upon carrier flight decks and it was quickly pulled from frontline service by the US Navy, although it saw service with the US Marine Corps during the Battle of Midway

The Brewster Buffalo Replacement

The various design issues with the Buffalo prompted the US Navy to go back to Grumman. By this time the firm had come up with a suitable monoplane fighter design, the first prototype of which had flown in September 1937 and easily outperformed the Brewster monoplane fighter. The US Navy wasted no time and ordered seventy-three units of the new Grumman fighter design in August 1939, for testing, and designated it the F4F-3.

Delivery of the F4F-3 to the US Navy began in February 1940. It had a supercharged 1,200 hp engine that gave the single-seat fighter a maximum speed of 331 mph. In March 1941, the first of ninety-five units of an improved model, labelled the F4F-3A, was delivered to the US Navy. It featured a slightly different 1,200 hp engine than the first model of the aircraft. It was also fitted with a simpler single-stage supercharger because there was a shortage of the two-stage supercharger found in the initial version of the aircraft.

Based on early British combat experience with the F4F-3, a new up-gunned and armored version was placed into production by Grumman in early 1942. The US Navy designated it the F4F-4 and named it the Wildcat. A total of 1,169 units were built. By the middle of 1942, it had replaced the majority of the earlier variants of the plane on US Navy carriers.

To allow Grumman to concentrate on building the next-generation fighter to replace the Wildcat, the US Navy assigned production of F4F aircraft to the Eastern Aircraft Division of General Motors, hereafter referred to as General Motors for the sake of brevity.

The General Motors near-copy of the Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat was labelled the FM-1. The General Motors FM-2 model of the Wildcat was based on two Grumman prototypes labelled the XF4F-8, powered by 1,350 hp engines. According to one reputable source, General Motors built 1,600 units of the FM-1 and 4,777 units of the FM-2, by 1945. Other sources quote different numbers of the FM-1 and FM-2 built.

Biplane Dive Bombers

Dive bombing, an RAF invention from the First World War, had been taken up by the US Marine Corps following the conflict and adopted by the US Navy in 1928. Dive bombing involved aiming an aircraft at an enemy ship while in a steep dive and releasing the bomb at a relatively low altitude for maximum accuracy. The steep angle of attack made it very hard for enemy ship-board anti-aircraft guns to engage attacking dive bombers.

The first dedicated biplane dive bomber for the US Navy was a Martin-designed single-engine biplane, referred to as the BM, with twenty-eight being ordered in 1931. It came in two models, the BM-1 and the BM-2. The letter ‘B’ in the aircraft prefix code stood for bomber and the ‘M’ for Martin. There was a swing-out ordnance cradle underneath the plane’s fuselages for a 1,000 lb bomb. Both versions of the BM dive bomber were pulled from US Navy frontline service in 1937.

The follow-on to the Martin BM-1 and BM-2 dive-bombers was the Great Lakes BG-1 dive bomber. The letter ‘B’ in the aircraft prefix code stood for bomber and the ‘G’ for Great Lakes Aircraft Company. Like the Martin product, the Great Lakes dive bomber was a single-engine biplane with a crew of two. The US Navy ordered the first batch in 1933 and the last in 1935. The order encompassed sixty units of the aircraft. It served in frontline US Navy carrier service from 1934 to 1938. The US Marine Corps employed the aircraft as a dive bomber until 1940.

Next in line were the Curtiss-Wright F11C-2 Goshawk and the F11C-3 Goshawk, in 1934 (already described in the text) that were considered both fighters and dive bombers. Employing fighters in a secondary role as dive bombers was eventually seen as comprising their primary job, so it was decided in 1934 to go back to employing dedicated dive bombers once again.

When the US Navy made the decision to field dedicated dive bombers in 1934, it also decided to assign these new specialized dive bombers a secondary role as scout planes. These two combined roles were now defined by assigning the letter prefix code ‘SB’ for scout-bomber. Hereafter in the text the term dive-bombers will be referred to as scout-bombers.

Biplane Scout-Bombers

A dedicated scout-bomber taken into service pre-war by the US Navy was the Vought SBU-1, which entered service in late 1935, with eighty-four units ordered. It had originally been designed for the US Navy as a two seat fighter, but as the service then wanted only single-seat fighters it was rejected. Forty units of an improved dedicated scout-bomber model designated the SBU-2 were delivered by Vought to the US Navy in 1937. Both aircraft were also referred to by the company as the Corsair, a name they would also use for many other aircraft.

The US Navy also sought out other firms to build dedicated scout-bombers. This included Curtiss-Wright who delivered in 1937 eighty-three units of an aircraft designated SBC-3. The last pre-war Curtiss-Wright dedicated scout-bomber delivered to the US Navy in early 1939 were eighty-nine units labelled the SBC-4, with fifty units being transferred to the French Government in June 1940. All the various models of the Curtiss-Wright-designed and built dedicated scout-bombers were referred to as ‘Helldivers’.

Monoplane Dive Bombers

The Northrop Company product came up with a monoplane scout-bomber designated the BT-1 in 1935. The ‘T’ in the letter designation code stood for Northrop, which became a division of the Douglas Aircraft Company in 1939. The BT-1 was not perfect, but the US Navy believed the design had potential and ordered fifty-four in 1936. A labour dispute delayed delivery to the US Navy until 1938. Once in service it proved unsuitable for carrier service and was pulled from use.

Fifty-seven units of an improved Northrop BT-1 design, initially referred to as the BT-2 and fitted with a more powerful engine, were delivered by Douglas to the US Navy in mid-1940. Once in production it was then labelled the SBD-1, with the letter ‘D’ in the designation code standing for Douglas. This first version of the aircraft was supplied to US Marine Corps squadrons. It was quickly followed by eighty-seven units of an improved SBD-2 model that same year that went to US Navy squadrons. The aircraft was nicknamed the ‘Dauntless’, as were follow-on versions.

In early 1941, the US Navy ordered 174 units of the SBD-3, with deliveries starting in March 1941. US entry into the Second World War in December 1941 resulted in the US Navy quickly ordering 500 additional units of the aircraft. In October 1942, the US Navy received the first of 780 units of the latest version of the Dauntless, designated the SDB-4.

Vought, not wanting to miss out on a business opportunity, wasted no time in providing the prewar US Navy with a series of new monoplane scout-bombers, beginning with fifty-four units of the SB2U-1, with the first delivered in mid-1937. It was followed by the delivery in 1938 of another model, labelled the SB2U-2, of which the US Navy ordered fifty-eight units. The final version of the aircraft ordered by the US Navy late in 1939 was the SB2U-3, and assigned the name ‘Vindicator’, the first of fifty-seven ordered being delivered in mid-1941.

Biplane Torpedo Bombers

The US Navy’s original post-First World War dedicated torpedo bomber was the twin-engine, shore-based Martin TM-1 of which they ordered ten units. The letter ‘T’ stood for torpedo and the ‘M’ for Martin. The aircraft had its initial flight in January 1920, and was also referred to as the MTB. Again, the ‘M’ being for Martin and the ‘TB’ for torpedo bomber.

The Philadelphia Naval Yard took it upon themselves in 1922 to modify an unsuccessful Curtiss twin-engine torpedo bomber design, referred to as the R-6-L, with a more powerful engine. This resulted in a new aircraft designated the PT-1, of which fifteen were built. It was superseded the following year by an improved version, designated PT-2, of which eighteen were constructed. The letter ‘P’ stood for Philadelphia Naval Yard, and the ‘T’ for torpedo.

To come up with a more modern shore-based torpedo bomber, the US Navy in 1922 arranged for a competition between four civilian firms. The winner of the contest was a single-engine Douglas design, designated by the US Navy as the DT-2, the letter ‘D’ standing for Douglas and the ‘T’ for torpedo.

The US Navy ordered ninety-three units of the DT-2, with the building of the aircraft divided among four entities; Douglas along with two other civilian firms and the NAF, the latter building five units of an improved version in 1923, known as the DT-4.

The Douglas DT-2 and DT-4 were followed by six prototypes of the Curtiss designed CS-1 and two of the CS-2 shore-based reconnaissance plane and torpedo-bomber. However, Martin underbid Curtiss for the construction of additional planes for the US Navy. Their copies were labelled the SC-1 and SC-2, with seventy-five units built, all of which were delivered in 1925.

Douglas managed to interest the US Navy in twelve units of another shore-based torpedo-bomber, designated the T2D-1 that were delivered in 1928. The US Navy ordered eighteen additional units of another version of the T2D-1 that came with folding wings and was intended for carrier duty. That never happened, and the aircraft was confined to shore bases.

The first carrier-based torpedo-bomber for the US Navy was twenty-four units of the Martin T3M-1; deliveries started in 1926. It was followed in 1927 by 100 units of an improved version, designated the T3M-2. The Martin T3M-1 and T3M-2 were replaced onboard US Navy carriers in 1930 by another Martin aircraft designated the T4M-1, of which 102 were acquired. However, at that point, the Martin factory had been acquired by the Great Lakes Aircraft Corporation, and the aircraft designation was changed to TG-1. It was followed by an improved version in 1931 referred to as the TG-2. In total, fifty units of the TG-1 and TG-2 were built for the US Navy.

Monoplane Torpedo-Bombers

As the Great Lake TG-1 and TG-2s were beginning to show their age in 1934, the US Navy began looking for a more advanced monoplane torpedo bomber. After testing the products of three different firms, they decided a Douglas product best met their needs. That aircraft first entered service in July 1937 and was designated the TBD-1. The letters ‘TB’ were the new designation code for torpedo bombers and the letter ‘D’ obviously for Douglas. One hundred and thirty units of the TBD-1 were acquired by the US Navy between 1937 and 1939.

The TBD-1 was named the ‘Devastator’ in late 1941 and was assigned to all the pre-Second World War US Navy fleet carriers. In the May 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea, the Devastators performed well and helped to sink a Japanese light aircraft carrier. However, during the Battle of Midway the following month, their slow attack speed and lack of manoeuvrability made them easy targets for enemy shipboard anti-aircraft defenses, as well as defending fighters. The US Navy pulled all the remaining Devastators off its carriers shortly afterwards and confined them to secondary duties, until the last were pulled from service in 1944.